|

by Bill Gross

Janus Capital July 6, 2016 If only Fed Governors and Presidents understood a little bit more about Monopoly, and a tad less about outdated historical models such as the Taylor Rule and the Phillips Curve, then our economy and its future prospects might be a little better off. That is not to say that Monopoly can illuminate all of the problems of our current economic stagnation. Brexit and a growing Populist movement clearly point out that the possibility of de-globalization (less trade, immigration and economic growth) is playing a part. And too, structural elements long ago advanced in my New Normal thesis in 2009 have a significant role as well: aging demographics, too much debt, and technological advances including job-threatening robotization are significantly responsible for 2% peak U.S. real GDP as opposed to 4-5% only a decade ago. But all of these elements are but properties on a larger economic landsc ape best typified by a Monopoly board. In that game, capitalists travel around the board, buying up properties, paying rent, and importantly passing “Go” and collecting $200 each and every time. And it’s the $200 of cash (which in the economic scheme of things represents new “credit”) that is responsible for the ongoing health of our finance-based economy. Without new credit, economic growth moves in reverse and individual player “bankruptcies” become more probable. But let’s start back at the beginning when the bank hands out cash, and each player begins to roll the dice. The bank – which critically is not the central bank but the private banking system– hands out $1,500 to each player. The object is to buy good real estate at a cheap price and to develop properties with houses and hotels. But the player must have a cash reserve in case she lands on other properties and pays rent. So at some point, the process of economic development represented by the building of houses and hotels slows down. You can’t just keep buying houses if you expect to pay other players rent. You’ll need cash or “credit”, and you’ve spent much of your $1,500 buying properties. To some extent, growth for all the players in general can continue but at a slower pace – the economy slows down due to a more levered position for each player but still grows because of the $200 that each receives as he passes Go. But here’s the rub. In Monopoly, the $200 of credit creation never changes. It’s always $200. If the rules or the system allowed for an increase to $400 or say $1,000, then players could keep on building and the economy keep growing without the possibility of a cash or credit squeeze. But it doesn’t. The rules which fix the passing “Go” amount at $200 ensure at some point the breakdown of a player who hasn’t purchased “well” or reserved enough cash. Bankruptcies begin. The Monopoly game, which at the start was so exciting as $1,500 and $200 a pass made for asset accumulation and economic growth, now tur ns sullen and competitive: Dog eat dog with the survival of many of the players on the board at risk. All right. So how is this relevant to today’s finance-based economy? Hasn’t the Fed printed $4 trillion of new money and the same with the BOJ and ECB? Haven’t they effectively increased the $200 “pass go” amount by more than enough to keep the game going? Not really. Because in today’s modern day economy, central banks are really the “community chest”, not the banker. They have lots and lots of money available but only if the private system – the economy’s real bankers – decide to use it and expand “credit”. If banks don’t lend, either because of risk to them or an unwillingness of corporations and individuals to borrow money, then credit growth doesn’t increase. The system still generates $200 per player per round trip roll of the dice, but it’s not enough to keep real GDP at the same pace and to prevent some companies/households from going bankrupt. That is what’s happening today and has been happening for the past few years. As shown in Chart I, credit growth which has averaged 9% a year since the beginning of this century barely reaches 4% annualized in most quarters now. And why isn’t that enough? Well the proof’s in the pudding or the annualized GDP numbers both here and abroad. A highly levered economic system is dependent on credit creation for its stability and longevity, and now it is growing sub-optimally. Yes, those structural elements mentioned previously are part of the explanation. But credit is the oil that lubes the system, the straw that stirs the drink, and when the private system (not the central bank) fails to generate sufficient credit growth, then real economic growth stalls and even goes in reverse. (To elaborate just slightly, total credit, unlike standard “money supply” definitions include all credit or debt from households, businesses, government, and finance-based sources. It now totals a staggering $62 trillion in contrast to M1/M2 totals which approximate $13 trillion at best.) Now many readers may be familiar with the axiomatic formula of (“M V = PT”), which in plain English means money supply X the velocity of money = PT or Gross Domestic Product (permit me the simplicity for sake of brevity). In other words, money supply or “credit” growth is not the only determinant of GDP but the velocity of that money or credit is important too. It’s like the grocery store business. Turnover of inventory is critical to profits and in this case, turnover of credit is critical to GDP and GDP growth. Without elaboration, because this may be getting a little drawn out, velocity of credit is enhanced by lower and lower interest rates. Thus, over the past 5-6 years post-Lehman, as the private system has created insufficient credit growth, the lower and lower interest rates have increased velocity and therefore increased GDP, although weakly. No w, however with yields at near zero and negative on $10 trillion of global government credit, the contribution of velocity to GDP growth is coming to an end and may even be creating negative growth as I’ve argued for the last several years. Our credit-based financial system is sputtering, and risk assets are reflecting that reality even if most players (including central banks) have little clue as to how the game is played. Ask Janet Yellen for instance what affects the velocity of credit or even how much credit there is in the system and her hesitant answer may not satisfy you. They don’t believe in Monopoly as the functional model for the modern day financial system. They believe in Taylor and Phillips and warn of future inflation as we approach “full employment”. They worship false idols. To be fair, the fiscal side of our current system has been nonexistent. We’re not all dead, but Keynes certainly is. Until governments can spend money and replace the animal spirits lacking in the private sector, then the Monopoly board and meager credit growth shrinks as a future deflationary weapon. But investors should not hope unrealistically for deficit spending any time soon. To me, that means at best, a ceiling on risk asset prices (stocks, high yield bonds, private equity, real estate) and at worst, minus signs at year’s end that force investors to abandon hope for future returns compared to historic examples. Worry for now about the return “of” your money, not the return “on” it. Our Monopoly-based economy requires credit creation and if it stays low, the future losers will grow in number. by Bill Gross

Janus Capital June 2, 2016 The economist Joseph Schumpeter once remarked that the “top-dollar rooms in capitalism’s grand hotel are always occupied, but not by the same occupants”. There are no franchises, he intoned — you are king for a figurative day, and then — well — you move to another room in the castle; hopefully not the dungeon, which is often the case. While Schumpeter’s observation has obvious implications for one and all, including yours truly, I think it also applies to markets, various asset classes, and what investors recognize as “carry”. That shall be my topic of the day, as I observe the Pacific Ocean from Janus’ fourteenth floor — not exactly the penthouse but there is space available on the higher floors, and I have always loved a good view. Anyway, my basic thrust in this Outlook will be to observe that all forms of “carry” in financial markets are compressed, resulting in artificially high asset prices and a distortion of future risk relative to potential return that an investor must confront. Experienced managers that have treaded markets for several decades or more recognize that their “era” has been a magnificent one despite many “close calls” characterized by Lehman, the collapse of NASDAQ 5000, the Savings + Loan crisis in the early 90’s, and so on. Chart 1 proves the point for bonds. Since the inception of the Barclays Capital U.S. Aggregate or Lehman Bond index in 1976, investment grade bond markets have provided conservative investors with a 7.47% compound return with remarkably little volatility. An observer of the graph would be amazed, as was I, at the steady climb of wealth, even during significant bear markets when 30-year Treasury yields reached 15% in the early 80’s and were tagged with the designation of “certificates of confiscation”. The graph proves otherwise, because as bond prices were going down, the hig her and higher annual yields smoothed the damage and even led to positive returns during “headline” bear market periods such as 1979-84, or more recently the “taper tantrum” of 2013. Quite remarkable, isn’t it? A Sherlock Holmes sleuth interested in disproving this thesis would find few 12-month periods of time where the investment grade bond market produced negative returns. The path of stocks has not been so smooth but the annual returns (with dividends) have been over 3% higher than investment grade bonds as Chart 2 shows. That is how it should be: stocks displaying higher historical volatility but more return. But my take from these observations is that this 40-year period of time has been quite remarkable – a grey if not black swan event that cannot be repeated. With interest rates near zero and now negative in many developed economies, near double digit annual returns for stocks and 7%+ for bonds approach a 5 or 6 Sigma event, as nerdish market technocrats might describe it. You have a better chance of observing another era like the previous 40-year one on the planet Mars than you do here on good old Earth. The “top dollar rooms in the financial market’s grand hotel” may still be occupied by attractive relative asset classes, but the room rate is extremely high and the view from the penthouse is shrouded in fog, which is my meteorological metaphor for high risk. Let me borrow some excellent work from another investment firm that has occupied the upper floors of the market’s grand hotel for many years now. GMO’s Ben Inker in his first quarter 2016 client letter makes the point that while it is obvious that a 10-year Treasury at 1.85% held for 10 years will return pretty close to 1.85%, it is not widely observed that the rate of return of a dynamic “constant maturity strategy” maintaining a fixed duration on a Barclays Capital U.S. Aggregate portfolio now yielding 2.17%, will almost assuredly return between 1.5% and 2.9% over the next 10 years, even if yields double or drop to 0% at period’s end. The bond market’s 7.5% 40-year historical return is just that – history. In order to duplicate that number, yields would have to drop to -17%! Tickets to Mars, anyone? The case for stocks is more complicated of course with different possibilities for growth, P/E ratios and potential government support in the form of “Hail Mary” QE’s now employed in Japan, China, and elsewhere. Equities though, reside on the same planet Earth and are correlated significantly to the return on bonds. Add a historical 3% “equity premium” to GMO’s hypothesis on bonds if you dare, and you get to a range of 4.5% to 5.9% over the next 10 years, and believe me, those forecasts require a foghorn warning given current market and economic distortions. Capitalism has entered a new era in this post-Lehman period due to unimaginable monetary policies and negative structural transitions that pose risk to growth forecasts and the historical linear upward slope of productivity. Here’s my thesis in more compact form: For over 40 years, asset returns and alpha generation from penthouse investment managers have been materially aided by declines in interest rates, trade globalization, and an enormous expansion of credit – that is debt. Those trends are coming to an end if only because in some cases they can go no further. Those historic returns have been a function of leverage and the capture of “carry”, producing attractive income and capital gains. A repeat performance is not only unlikely, it is impossible unless you are a friend of Elon Musk and you’ve got the gumption to blast off for Mars. Planet Earth does not offer such opportunities. “Carry” in almost all forms is compressed and offers more risk than potential return. I will be specific: • Duration is unquestionably a risk in negative yielding markets. A minus 25 basis point yield on a 5-year German Bund produces nothing but losses five years from now. A 45 basis point yield on a 30-year JGB offers a current “carry” of only 40 basis points per year for a near 30-year durational risk. That’s a Sharpe ratio of .015 at best, and if interest rates move up by just 2 basis points, an investor loses her entire annual income. Even 10-year U.S. Treasuries with a 125 basis point “carry” relative to current money market rates represent similar durational headwinds. Maturity extension in order to capture “carry” is hardly worth the risk. • Similarly, credit risk or credit “carry” offers little reward relative to potential losses. Without getting too detailed, the advantage offered by holding a 5-year investment grade corporate bond over the next 12 months is a mere 25 basis points. The IG CDX credit curve offers a spread of 75 basis points for a 5-year commitment but its expected return over the next 12 months is only 25 basis points. An investor can only earn more if the forward credit curve – much like the yield curve – is not realized. • Volatility. Carry can be earned by selling volatility in many areas. Any investment longer or less creditworthy than a 90-day Treasury Bill sells volatility whether a portfolio manager realizes it or not. Much like the “VIX®”, the Treasury “Move Index” is at a near historic low, meaning there is little to be gained by selling outright volatility or other forms in duration and credit space. • Liquidity. Spreads for illiquid investments have tightened to historical lows. Liquidity can be measured in the Treasury market by spreads between “off the run” and “on the run” issues – a spread that is nearly nonexistent, meaning there is no “carry” associated with less liquid Treasury bonds. Similar evidence exists with corporate CDS compared to their less liquid cash counterparts. You can observe it as well in the “discounts” to NAV or Net Asset Value in closed-end funds. They are historically tight, indicating very little “carry” for assuming a relatively illiquid position. The “fact of the matter” – to use a politician’s phrase – is that “carry” in any form appears to be very low relative to risk. The same thing goes with stocks and real estate or any asset that has a P/E, cap rate, or is tied to present value by the discounting of future cash flows. To occupy the investment market’s future “penthouse”, today’s portfolio managers – as well as their clients, must begin to look in another direction. Returns will be low, risk will be high and at some point the “Intelligent Investor” must decide that we are in a new era with conditions that demand a different approach. Negative durations? Voiding or shorting corporate credit? Buying instead of selling volatility? Staying liquid with large amounts of cash? These are all potential “negative” carry positions tha t at some point may capture capital gains or at a minimum preserve principal. But because an investor must eat something as the appropriate reversal approaches, the current penthouse room service menu of positive carry alternatives must still be carefully scrutinized to avoid starvation. That means accepting some positive carry assets with the least amount of risk. Sometime soon though, as inappropriate monetary policies and structural headwinds take their toll, those delicious “carry rich and greasy” French fries will turn cold and rather quickly get tossed into the garbage can. Bon Appetit! by George Soros

Project Syndicate June 25, 2016 Britain, I believe, had the best of all possible deals with the European Union, being a member of the common market without belonging to the euro and having secured a number of other opt-outs from EU rules. And yet that was not enough to stop the United Kingdom’s electorate from voting to leave. Why? The answer could be seen in opinion polls in the months leading up to the “Brexit” referendum. The European migration crisis and the Brexit debate fed on each other. The “Leave” campaign exploited the deteriorating refugee situation – symbolized by frightening images of thousands of asylum-seekers concentrating in Calais, desperate to enter Britain by any means necessary – to stoke fear of “uncontrolled” immigration from other EU member states. And the European authorities delayed important decisions on refugee policy in order to avoid a negative effect on the British referendum vote, thereby perpetuating scenes of chaos like the one in Calais. German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to open her country’s doors wide to refugees was an inspiring gesture, but it was not properly thought out, because it ignored the pull factor. A sudden influx of asylum-seekers disrupted people in their everyday lives across the EU. The lack of adequate controls, moreover, created panic, affecting everyone: the local population, the authorities in charge of public safety, and the refugees themselves. It has also paved the way for the rapid rise of xenophobic anti-European parties – such as the UK Independence Party, which spearheaded the Leave campaign – as national governments and European institutions seem incapable of handling the crisis. Now the catastrophic scenario that many feared has materialized, making the disintegration of the EU practically irreversible. Britain eventually may or may not be relatively better off than other countries by leaving the EU, but its economy and people stand to suffer significantly in the short to medium term. The pound plunged to its lowest level in more than three decades immediately after the vote, and financial markets worldwide are likely to remain in turmoil as the long, complicated process of political and economic divorce from the EU is negotiated. The consequences for the real economy will be comparable only to the financial crisis of 2007-2008. That process is sure to be fraught with further uncertainty and political risk, because what is at stake was never only some real or imaginary advantage for Britain, but the very survival of the European project. Brexit will open the floodgates for other anti-European forces within the Union. Indeed, no sooner was the referendum’s outcome announced than France’s National Front issued a call for “Frexit,” while Dutch populist Geert Wilders promoted “Nexit.” Moreover, the UK itself may not survive. Scotland, which voted overwhelmingly to remain in the EU, can be expected to make another attempt to gain its independence, and some officials in Northern Ireland, where voters also backed Remain, have already called for unification with the Republic of Ireland. The EU’s response to Brexit could well prove to be another pitfall. European leaders, eager to deter other member states from following suit, may be in no mood to offer the UK terms – particularly concerning access to Europe’s single market – that would soften the pain of leaving. With the EU accounting for half of British trade turnover, the impact on exporters could be devastating (despite a more competitive exchange rate). And, with financial institutions relocating their operations and staff to eurozone hubs in the coming years, the City of London (and London’s housing market) will not be spared the pain. But the implications for Europe could be far worse. Tensions among member states have reached a breaking point, not only over refugees, but also as a result of exceptional strains between creditor and debtor countries within the eurozone. At the same time, weakened leaders in France and Germany are now squarely focused on domestic problems. In Italy, a 10% fall in the stock market following the Brexit vote clearly signals the country’s vulnerability to a full-blown banking crisis – which could well bring the populist Five Star Movement, which has just won the mayoralty in Rome, to power as early as next year. None of this bodes well for a serious program of eurozone reform, which would have to include a genuine banking union, a limited fiscal union, and much stronger mechanisms of democratic accountability. And time is not on Europe’s side, as external pressures from the likes of Turkey and Russia – both of which are exploiting the discord to their advantage – compound Europe’s internal political strife. That is where we are today. All of Europe, including Britain, would suffer from the loss of the common market and the loss of common values that the EU was designed to protect. Yet the EU truly has broken down and ceased to satisfy its citizens’ needs and aspirations. It is heading for a disorderly disintegration that will leave Europe worse off than where it would have been had the EU not been brought into existence. But we must not give up. Admittedly, the EU is a flawed construction. After Brexit, all of us who believe in the values and principles that the EU was designed to uphold must band together to save it by thoroughly reconstructing it. I am convinced that as the consequences of Brexit unfold in the weeks and months ahead, more and more people will join us. by Mat Clinch

CNBC June 22, 2016 The organization commonly known as the central bank of central banks has called for an end of boom-and-bust cycles that have plagued the global economy, urging lawmakers quickly to adjust current policy. "The global economy cannot afford to rely any longer on the debt-fueled growth model that has brought it to the current juncture." the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) warns in a new annual report published on Sunday. Debt levels are too high, productivity growth is too low, and the room for policy maneuver is too narrow, the BIS warned. Adding that the most "conspicuous" sign of this predicament is interest rates that continue to be persistently and exceptionally low. Central banks around the world have leapt into action following the global financial crisis of 2008 and the sovereign debt crisis in the euro zone. Several institutions have introduced bond-buying programs and cut benchmark rates in an effort to stimulate lending. Some have even pushed rates below zero with a negative rate effectively charging banks who park cash at a central bank. The European Central Bank (ECB), the Danish National Bank (DNB), the Swedish Riksbank, and the Swiss National Bank (SNB) have all pushed key short-term policy rates into negative territory. This has suppressed bond yields in wider asset markets with BIS estimating that a record of close to $8 trillion in sovereign debt was trading at negative yields at the end of May. Nonetheless, the Basel-based BIS - which was one of the few organizations to foresee the 2008 crash - says that this monetary policy has been "overburdened for far too long." "Prudential, fiscal and, above all, structural policies must come to the fore," it said in the report Wednesday, adding that it's essential to avoid the temptation to succumb to "quick fixes or shortcuts." "The measures must retain a firm long-run orientation. We need policies that we will not once again regret when the future becomes today," it added. The BIS calls for the completion of banking rules on capital buffers to help in times of stress, and stresses that "stronger banks lend more." It also calls on governments to adjust their fiscal - or budgetary - rules to make them more countercyclical and reduce implicit guarantees, which may encourage risk-taking. Another policy that deserves consideration, according to BIS, is to use the tax code to restrict or eliminate the bias of debt over equity or reduce the effect of financial cycles The organization is renowned for its analysis of central banking and has regularly warned over the effects of stimuli such as quantitative easing. However, it was moderately upbeat on the global economy with regards to growth. "Judged by standard benchmarks, the global economy is not doing as badly as the rhetoric sometimes suggests," it said. "Global growth continues to disappoint expectations but is in line with pre-crisis historical averages, and unemployment continues to decline." by Joseph Ciolli

June 24, 2016 Selling in the U.S. stock market in the wake of the U.K.’s decision to secede from the European Union is just getting started for quantitative traders who make buy or sell decisions based on price trends, according to UBS Group AG. Their sales could total as much as $150 billion should equity volatility persist in the S&P 500 Index for the next week, derivatives strategist Rebecca Cheong said on Friday. The benchmark stock gauge fell 2.3 percent to 2,054.25 at 11:27 a.m. in New York, erasing a 2 percent rally over the prior four days. Strategies designed to mitigate risk will actually add to downward pressure in the S&P 500 over the next week as computerized selling ramps up to keep pace with falling prices. It reminds Cheong of the rapid stock selling that roiled markets in August, when the S&P 500 fell 11 percent to a 10-month low while facing similar behavior from algorithmic traders. “The bigger the down move today, the more they have to sell, which would basically create a vicious cycle,” Cheong, head of Americas equity derivatives strategy at UBS, said in a phone interview. “We’ll see front-loaded selling in the range of $100 billion to $150 billion over the next two to three days. It could be very similar to August in terms of model-based selling.” Rebalancing of risk control funds could result in up to $98 billion in S&P 500 selling should the index see price swings of about 3.5 percent or more over the next several days, according to Cheong. Risk parity instruments may stir up as much as $30 billion in selling given similar volatility, she said. Additional downward price momentum will be created as owners of leveraged exchange-traded funds linked to the CBOE Volatility Index buy more shares as part of their own rebalancing process, according to UBS. The volatility index, which generally trades inversely to the S&P 500, climbed 27 percent on Friday. “They’ll be buying volatility and selling the S&P,” said Cheong. “On days like today, when the VIX goes up, they have to buy.” by Leslie Shaffer

CNBC June 10, 2016 Central banks are essentially out of ammunition, with zero and negative interest rate policies spurring greater savings, not growth, said Michael Heise, chief economist at Allianz Group. Moves by central banks from Japan to the euro zone to slash interest rates below zero have upended financial markets: investors are now paying some governments for the privilege of parking their funds while commercial lenders are mulling storing their cash in costly vaults instead of keeping them with central banks. Despite the stimulus, economic growth remains feeble. "Monetary policy has basically run its course in stimulating the economies," said Heise in an exclusive interview with CNBC in Singapore. "The Japanese example is very telling." In late January, the Bank of Japan blindsided global financial markets by adopting negative interest rates for the first time ever - a move that should have spurred outflows of the local currency. But instead, the yen surged and signs of the intended effects, such as increased bank loans, have been scarce. "The impact of monetary policy is actually counter intuitive and that shows that there's a lot of uncertainty that policy makers are facing," Heise said. "They can't even be sure how their instruments are going to affect the economy." For one, the chief economist at Allianz, which had 1.723 trillion euros ($1.95 trillion) under management as of the end of 2015, noted that low-to-negative rates aren't encouraging spending, which is what textbook economics would suggest. "It is quite remarkable that savings rates are not going down, although savings in terms of return is completely unattractive," he said. Instead, he added, "there's a concern that the wealth not accumulating in a way that [people] can take care of their retirement income or other objectives you have when you save: for buying a house or protecting your children or sending your children to school." That's made the savings ratio "completely inelastic," while low capital costs have done the same to dampen investment, he said, noting that consumption has only been rising in Germany because of salary increases. A low cost of capital means that the "opportunity cost" -- or the cost of making one investment as opposed to another or not investing at all -- is also low, which may encourage companies to simply wait on the sidelines. Low interest rates have also not spurred bank loans, he noted. "Bank lending does not accelerate just because of low interest rates or a lot of liquidity. Liquidity was never the problem for bank lending," Heise said. "It's the capital situation of the banks and lack of demand for loans by the corporate sector and the households." But he pointed to signs this is changing in Europe as the economy there recovers. "Slowly, companies are becoming more courageous to take up some loans, but it does not have to do with the buying of government bonds by the European Central Bank," he said. But he noted that within Asia, he's hearing a shift toward structural reforms, rather than relying on monetary policy. "We've completely exploited that and it's high time to refocus on other policies," Heise said, noting that these efforts may vary across countries, such as reforming inefficient state-owned enterprises, focusing on infrastructure and education spending, attracting foreign investment or fighting corruption. But when it comes to the U.S. Federal Reserve, Heise still expects interest rate increases ahead. After last week's non-farm payrolls report came in well-below expectations, many analysts pushed back their expectations for an interest rate hike from previous forecast for June or July. But Heise said that while a June move was likely off the table, he still put a greater than 50 percent chance that the Fed will hike interest rates at its July meeting. He said there's still too many reasons for the Fed to move and that the labor market appeared to remain in fairly good shape, with some wage-growth acceleration, although there was room for the participation rate to rise. GS - One large drawdown can quickly erase returns that were accumulated over several years10/6/2016

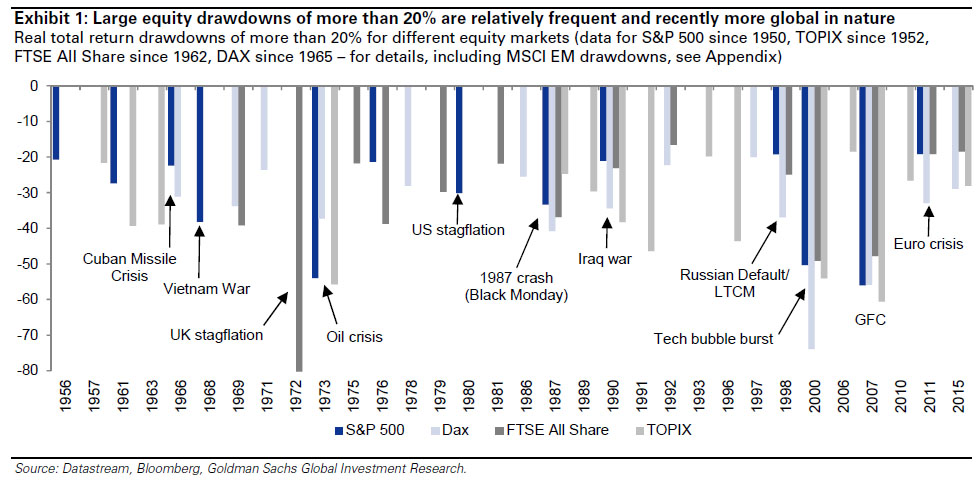

Goldman Sachs: "since the 1950s most equity markets had several large drawdowns of more than 20%, which have taken several years to recover from. For example in the 1970s the FTSE All-Share had an 80% drawdown in real terms and the DAX declined 69% during the Tech Bubble. One of the largest equity drawdowns across markets was during the GFC, when most global equity markets lost around half their value. And not to forget, the TOPIX has still not recovered from the large drawdowns of the late1980s/early 1990s."

by Gregory Zuckerman

Wall Street Journal June 8, 2016 After a long hiatus, George Soros has returned to trading, lured by opportunities to profit from what he sees as coming economic troubles. Worried about the outlook for the global economy and concerned that large market shifts may be at hand, the billionaire hedge-fund founder and philanthropist recently directed a series of big, bearish investments, according to people close to the matter. Soros Fund Management LLC, which manages $30 billion for Mr. Soros and his family, sold stocks and bought gold and shares of gold miners, anticipating weakness in various markets. Investors often view gold as a haven during times of turmoil. The moves are a significant shift for Mr. Soros, who earned fame with a bet against the British pound in 1992, a trade that led to $1 billon of profits. In recent years, the 85-year-old billionaire has focused on public policy and philanthropy. He is also a large contributor to the super PAC backing presumptive Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton and has donated to other groups supporting Democrats. Mr. Soros has always closely monitored his firm’s investments. In the past, some senior executives bristled at how he sometimes inserted himself into the firm’s operations, usually after the fund suffered losses, according to people familiar with the matter. But in recent years, he hasn’t done much investing of his own. That changed earlier this year when Mr. Soros began spending more time in the office directing trades. He has also been in more frequent contact with the executives, the people said. In some ways, Mr. Soros is stepping into a void at his firm. Last year, Scott Bessent, who served as Soros’s top investor and has a background in macro investing, or anticipating macroeconomic moves around the globe, left the firm to start his own hedge fund. Soros has invested $2 billion with Mr. Bessent’s firm, Key Square Group. Later in 2015, Mr. Soros tapped Ted Burdick as his chief investment officer. Mr. Burdick has a background in distressed debt, arbitrage and other types of trading, rather than macro investing, Mr. Soros’s lifelong specialty. That is why Mr. Soros felt comfortable stepping back in, the people said. Mr. Soros’s recent hands-on approach reflects a gloomier outlook than many others on Wall Street. His worldview darkened over the past six months as economic and political issues in China, Europe and elsewhere have become more intractable, in his view. While the U.S. stock market has inched back toward record levels after troubles early this year and Chinese markets have stabilized, Mr. Soros remains skeptical of the Chinese economy, which is slowing. The fallout from any unwinding of Chinese investments likely will have global implications, Mr. Soros said in an email. “China continues to suffer from capital flight and has been depleting its foreign currency reserves while other Asian countries have been accumulating foreign currency,” Mr. Soros said. “China is facing internal conflict within its political leadership, and over the coming year this will complicate its ability to deal with financial issues.” Mr. Soros worries that new troubles will arise in China partly because he said the nation doesn’t seem willing to embrace a transparent political system that he contends is necessary to enact lasting economic overhauls. Beijing has embarked on overhauls in the past year but has backtracked on some efforts amid turbulent markets. Some investors are beginning to anticipate rising inflation amid recent wage gains in the U.S., but Mr. Soros said he is more concerned that continued weakness in China will exert deflationary pressure—a damaging spiral of falling wages and prices—on the U.S. and global economies. Mr. Soros also argues that there remains a good chance the European Union will collapse under the weight of the migration crisis, continuing challenges in Greece and a potential exit by the United Kingdom from the EU. “If Britain leaves, it could unleash a general exodus, and the disintegration of the European Union will become practically unavoidable,” he said. Still, Mr. Soros said recent strength in the British pound is a sign that a vote to exit the EU is less likely. “I’m confident that as we get closer to the Brexit vote, the ‘remain’ camp is getting stronger,” Mr. Soros said. “Markets are not always right, but in this case I agree with them.” Other big investors also have become concerned about markets. Last month, billionaire trader Stanley Druckenmiller warned that “the bull market is exhausting itself” and hedge-fund manager Leon Cooperman said “the bubble is in fixed income,” though he was sanguine on stocks. Mr. Soros’s bearish investments have had mixed success. His firm bought over 19 million shares of Barrick Gold Corp. in the first quarter, according to securities filings, making it the firm’s largest stockholding at the end of the quarter. That position has gained more than $90 million since the end of the first quarter. Soros Fund Management also bought a million shares of miner Silver Wheaton Corp. in the first quarter, a position that has increased 28% so far in the second quarter. Meanwhile, gold has climbed 19% this year. But Mr. Soros also adopted bearish derivative positions that serve as wagers against U.S. stocks. It isn’t clear when those positions were placed and at what levels during the first quarter, but the S&P 500 index has climbed 3% since the beginning of the second period, suggesting Mr. Soros could be facing losses on some of those moves. Overall, the Soros fund is up a bit this year, in line with most macro hedge funds, according to people close to the matter. The investments by the firm were previously disclosed in filings, but it wasn’t clear how involved Mr. Soros was in the decisions spurring the moves. The last time Mr. Soros became closely involved in his firm’s trading: 2007, when he became worried about housing and placed bearish wagers over two years that netted more than $1 billion of gains. by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

The Telegraph May 18, 2016 Nobody rings a bell at the top of the credit supercycle, to misuse an old adage. Except that this time somebody very powerful in China has done exactly that. China watchers are still struggling to identify the author of an electrifying article in the People's Daily that declares war on debt and the "fantasy" of perpetual stimulus. Written in a imperial tone, it commands China to break its addiction to credit and take its punishment before matters spiral out of control. If that means bankruptcies must run their course, so be it. Fifteen years ago such a mystery article would have been an arcane matter, of interest only to Sinologists. Today it is neuralgic for the entire global - and over-globalized - financial system. China's debt is approaching $30 trillion. The fresh credit alone created since 2007 is greater than the outstanding liabilities of the US, Japanese, German, and Indian commercial banking systems combined. Moody's warned this month that China's state-owned entities (SOEs) have alone racked up debts of 115pc of GDP, and a fifth may require restructuring. The defaults are already spreading up the ladder from local SOE's to the bigger state behemoths, once thought - wrongly - to have a sovereign guarantee. To put matters in context, leverage rose by roughly 50 percentage points of GDP in Japan before the Nikkei bubble burst in 1990, or in Korea before the East Asia crisis in 1998, or in the US before the subprime debacle. This gauge is an almost mechanical indicator of a future credit crisis. As we all know, China is in a class of its own. Debt has risen by 120 to 140 percentage points. The scale of excess industrial capacity - and China's power and life and death over commodity markets - mean that any serious policy pivot by the Communist Party would set off an international earthquake. Hence the fevered speculation about this strange article published on May 9 in the house journal of the Politburo. It was no ordinary screed. The 11,000 character text - citing an "authoritative person" - was given star-billing on the front page. It described leverage as the "original sin" from which all other risks emanate, with debt “growing like a tree in the air”. It warned of a "systemic financial crisis" and demanded a halt to the "old methods" of reflexive stimulus every time growth falters. "It is neither possible nor necessary to force economic growing by levering up," it said. It called for root-and-branch reform of the SOE's - the redoubts of vested interests and the patronage machines of party bosses - with an assault on "zombie companies". Local governments were ordered to abandon their illusions and accept the inevitable slide in tax revenues, and the equally inevitable rise in unemployment. If China does not bite the bullet now, the costs will be "much higher" in the future. "China’s economic performance will not be U-shaped and definitely not V-shaped. It will be L-shaped," said the text. We have been warned. Jonathan Fenby, a China veteran at Trusted Sources, says you can interpret the piece in two very different ways: either as a "call to arms" after three years of foot-dragging on the Third Plenum reforms, or the "last gasp for reformers who see their agenda slipping away." "We see the current state of affairs as very much resembling the old imperial court, where various factions fight for attention of the undisputed leader – namely, Xi," he said. Mr Fenby compares it to the Qing Dynasty in the late 19th century, when reformers battling to modernize the economy were ultimately defeated by the old guard. The same pattern recurred under Chiang Kai-Shek's Kuomintang in the 1920s and 1930s. Each time it ended in stagnation. The difference today is that China is vastly more important to the world economy. Most think the author was either President Xi Jinping himself, or his right-hand man Liu He - who handles daily operations for the 'Leading Group', China's version of the White House National Economic Council. A day later the People's Daily published a hitherto closed-door speech by Mr Xi lashing out at "careerists and conspirators existing in our Party and undermining the Party's governance”. He denounced the latest property bubble and excesses in the banking system, but confusingly he also laced his talk with quotes from Confucious, Mao, and Marx - the latter increasingly part of his discourse as he invokes dialectical materialism and other such forgotten gems. It was the usual incoherence we expect from the new Helmsman. He may not be the clear-thinking mystery man after all, yet it would courting fate to ignore the warnings from the People's Daily altogether. The latest stop-go credit cycle began in mid-2015 and has since accelerated to an epic blow-off, with the M1 money supply now growing at 22.9pc, by the fastest pace since the post-Lehman blitz. Wei Yao from Societe Generale estimates that total loans rose by $1.15 trillion in the first quarter, equivalent to 46pc of quarterly GDP. "This looks like an old-styled credit-backed investment-driven recovery, which bears an uncanny resemblance to the beginning of the 'four trillion stimulus' package in 2009. The consequence of that stimulus was inflation, asset bubbles and excess capacity," she said. House sales rose 60pc in April, despite curbs to cool the bubble. New starts were up 26pc. Prices jumped 63pc in Shenzhen, 34pc in Shanghai, 20pc in Beijing, and 18pc in Hefei. Panic buying is spreading to the smaller Tier 3 and 4 cities with the greatest glut. It all has echoes of the stockmarket boom and bust last year. "Investors are convinced that the government will guarantee that housing prices won't fall," said Professor Zhu Ning from the Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance, speaking to the South China Morning Post. It also sounds like Britain. There was a slight cooling in April but less than headlines suggested. The old measure of total social financing (TSF) slipped but this was more than offset by record bond issuance of $180bn. Together they reached a 26-month high. Capital Economics says budgeted funds must be disbursed by the end of this quarter under new finance ministry rules, implying another $310bn of bonds by late June. The fiscal boost will be 'front-loaded'. The money will pile up in accounts and flood the economy over the late summer. If the usual time-lags hold, the mini-boom will last for a few more months. Then the trouble will start. Needless to say, markets may roll over long before the economy itself. A number of western fund managers jumped the gun last year - including Britain's Crispin Odey -betting that the long-awaited China crisis was about to unfold. Some over-estimated the importance of the Shanghai equity fiasco; others mistook China's new currency regime for a devaluation (there was none), and many misread the credit, transport, and industrial data. Bloomberg reports that Roslyn Zhang from China's sovereign wealth fund (CIC) mocked them for their "herd mentality" at last week's Skybridge Alternatives conference in Las Vegas. “They really don’t know much about China but they just spend two seconds and put on the trade. Should we pay two and 20 for treatment like this?” she said, meaning the industry fee of 2pc in tithes and 20pc of profits. She vowed to cull amateurs mercilessly from CIC patronage. Yet this year the China bears may get their revenge, if they have any money left to play with. The rot in the country's $7.7 trillion bond markets is metastasizing. Bo Zhuang from Trusted Sources said more than 100 firms cancelled or delayed bond issues in April due to widening credit spreads. Ten companies have defaulted this year, with the shipbuilder Evergreen, Nanjing Yurun Foods, and the solar group Yingli Green Energy all in trouble this month. But what has really spooked markets is the suspension of nine bonds issued by the AA+ rated China Railways Materials, the first of the big central SOE's to signal default. "This has greatly weakened investors’ long-standing expectation of implicit government support," he said. Bo Zhuang said investors have poured money into bonds in the latest frenzy. The stock of corporate bonds has jumped by 78pc to $2.3 trillion over the last year. It is the epicentre of leverage through short-term 'repo' transactions, and it is now coming unstuck. "The experience with the stock market shows how difficult it can be to contain a reversal in leveraged bets. In our view, a bond market crisis would be much more destructive," he said. With luck, the rest of us outside China will have three or four more months to order our own affairs before the storm gathers. Whether it is bumpy landing, a hard landing, or a crash landing, depends on who the "authoritative person" in Beijing turn out to be. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed