|

84th Annual Report | 1 April 2013–31 March 2014

Basel, 29 June 2014 I. In search of a new compass The global economy has shown encouraging signs over the past year. But its malaise persists, as the legacy of the Great Financial Crisis and the forces that led up to it remain unresolved. To overcome that legacy, policy needs to go beyond its traditional focus on the business cycle. It also needs to address the longer-term build-up and run-off of macroeconomic risks that characterise the financial cycle and to shift away from debt as the main engine of growth. Restoring sustainable growth will require targeted policies in all major economies, whether or not they were hit by the crisis. Countries that were most affected need to complete the process of repairing balance sheets and implementing structural reforms. The current upturn in the global economy provides a precious window of opportunity that should not be wasted. In a number of economies that escaped the worst effects of the financial crisis, growth has been spurred by strong financial booms. Policy in those economies needs to put more emphasis on curbing the booms and building the strength to cope with a possible bust, and there, too, it cannot afford to put structural reforms on the back burner. Looking further ahead, dampening the extremes of the financial cycle calls for improvements in policy frameworks – fiscal, monetary and prudential – to ensure a more symmetrical response across booms and busts. Otherwise, the risk is that instability will entrench itself in the global economy and room for policy manoeuvre will run out. II. Global financial markets under the spell of monetary policy Financial markets have been acutely sensitive to monetary policy, both actual and anticipated. Throughout the year, accommodative monetary conditions kept volatility low and fostered a search for yield. High valuations on equities, narrow credit spreads, low volatility and abundant corporate bond issuance all signalled a strong appetite for risk on the part of investors. At times during the past year, emerging market economies proved vulnerable to shifting global conditions; those economies with stronger fundamentals fared better, but they were not completely insulated from bouts of market turbulence. By mid-2014, investors again exhibited strong risk-taking in their search for yield: most emerging market economies stabilised, global equity markets reached new highs and credit spreads continued to narrow. Overall, it is hard to avoid the sense of a puzzling disconnect between the markets’ buoyancy and underlying economic developments globally. III. Growth and inflation: drivers and prospects World economic growth has picked up, with advanced economies providing most of the uplift, while global inflation has remained subdued. Despite the current upswing, growth in advanced economies remains below pre-crisis averages. The slow growth in advanced economies is no surprise: the bust after a prolonged financial boom typically coincides with a balance sheet recession, the recovery from which is much weaker than in a normal business cycle. That weakness reflects a number of factors: supply side distortions and resource misallocations, large debt and capital stock overhangs, damage to the financial sector and limited policy room for manoeuvre. Investment in advanced economies in relation to output is being held down mostly by the correction of previous financial excesses and long-run structural forces. Meanwhile, growth in emerging market economies, which has generally been strong since the crisis, faces headwinds. The current weakness of inflation in advanced economies reflects not only slow domestic growth and a low utilisation of domestic resources, but also the influence of global factors. Over the longer term, raising productivity holds the key to more robust and sustainable growth. IV. Debt and the financial cycle: domestic and global Financial cycles encapsulate the self-reinforcing interactions between perceptions of value and risk, risk-taking and financing constraints, which translate into financial booms and busts. Financial cycles tend to last longer than traditional business cycles. Countries are currently at very different stages of the financial cycle. In the economies most affected by the 2007–09 financial crisis, households and firms have begun to reduce their debt relative to income, but the ratio remains high in many cases. In contrast, a number of the economies less affected by the crisis find themselves in the late stages of strong financial booms, making them vulnerable to a balance sheet recession and, in some cases, serious financial distress. At the same time, the growth of new funding sources has changed the character of risks. In this second phase of global liquidity, corporations in emerging market economies are raising much of their funding from international markets and thus are facing the risk that their funding may evaporate at the first sign of trouble. More generally, countries could at some point find themselves in a debt trap: seeking to stimulate the economy through low interest rates encourages even more debt, ultimately adding to the problem it is meant to solve. V. Monetary policy struggles to normalise Monetary policy has remained very accommodative while facing a number of tough challenges. First, in the major advanced economies, central banks struggled with an unusually sluggish recovery and signs of diminished monetary policy effectiveness. Second, emerging market economies and small open advanced economies contended with bouts of market turbulence and with monetary policy spillovers from the major advanced economies. National authorities in the latter have further scope to take into account the external effects of their actions and the corresponding feedback on their own jurisdictions. Third, a number of central banks struggled with how best to address unexpected disinflation. The policy response needs to carefully consider the nature and persistence of the forces at work as well as policy’s diminished effectiveness and side effects. Finally, looking forward, the issue of how best to calibrate the timing and pace of policy normalisation looms large. Navigating the transition is likely to be complex and bumpy, regardless of communication efforts. And the risk of normalising too late and too gradually should not be underestimated. VI. The financial system at a crossroads The financial sector has gained some strength since the crisis. Banks have rebuilt capital (mainly through retained earnings) and many have shifted their business models towards traditional banking. However, despite an improvement in aggregate profitability, many banks face lingering balance sheet weaknesses from direct exposure to overindebted borrowers, the drag of debt overhang on economic recovery and the risk of a slowdown in those countries that are at late stages of financial booms. In the current financial landscape, market-based financial intermediation has expanded, notably because banks face a higher cost of funding than some of their corporate clients. In particular, asset management companies have grown rapidly over the past few years and are now a major source of credit. Their larger role, together with high size concentration in the sector, may influence market dynamics and hence the cost and availability of funding for firms and households. What is the VXO?

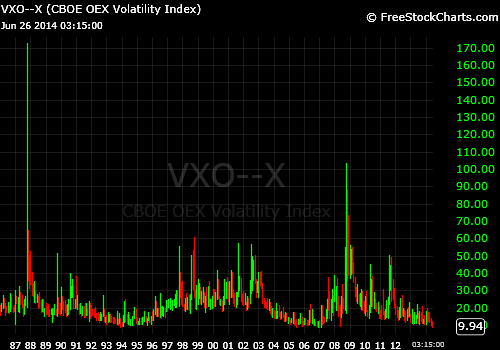

"The CBOE Volatility Index® (VIX®) is a key measure of market expectations of near-term volatility conveyed by S&P 500 stock index option prices. Since its introduction in 1993, VIX has been considered by many to be the world's premier barometer of investor sentiment and market volatility. The CBOE began disseminating prices for a VIX Index with a new methodology (Acrobat .pdf) on September 22, 2003." - Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) Prior to September 22, 2003, the "VIX" was based on the OEX 100, "a sub-set of the S&P 500, measures the performance of large cap companies in the United States. The Index comprises 100 major, blue chip companies across multiple industry groups." - S&P Dow Jones The VXO continues to trade as a more concentrated version of the VIX die to its focus on large-cap stocks. By Stanley Druckenmiller and Kevin Warsh

Wall Street Journal | June 19, 2014 Economist Richard Koo diagnosed Japan's crash in the early 1990s and subsequent two decades of economic malaise as a "balance-sheet recession." That conclusion wasn't lost on the Federal Reserve during the financial crisis of 2008-09. The Fed engineered an emergency response to craft what can best be described as a balance-sheet recovery. At its policy meeting earlier this week, the Fed made clear that it's scarred, if no longer scared, by the crisis. Extraordinarily loose monetary policy will continue in force. While the Fed's monthly asset purchases will decline, short-term interest rates will remain pinned near zero. And long-term rates need not move higher—the Fed assures us—even with improving inflation dynamics, credit markets priced-for-perfection, and stock prices at record levels. The aggregate wealth of U.S. households, including stocks and real-estate holdings, just hit a new high of $81.8 trillion. That's more than $26 trillion in wealth added since 2009. No wonder most on Wall Street applaud the Fed's unrelenting balance-sheet recovery strategy. It's great news for those households and businesses with large asset holdings, high risk tolerances and easy access to credit. Yet it provides little solace for families and small businesses that must rely on their income statements to pay the bills. About half of American households do not own any stocks and more than one-third don't own a residence. Never mind the retirees who are straining to make the most of their golden years on bond returns. The Fed's extraordinary tools are far more potent in goosing balance-sheet wealth than spurring real income growth. The most recent employment report reveals the troubling story for Main Street. While 217,000 jobs were created in May, incomes for most Americans remain under stress, with only modest improvements in hours worked and average hourly earnings. It's taken a full 76 months for the number of people working to get back to its previous peak, a discomfiting postwar record. Unfortunately, during the same period the U.S. working-age population increased by more than 15 million people. That's why the share of the working-age population out of work is now at a 36-year low. There are now more Americans on disability insurance than are working in construction and education, combined. Meanwhile, corporate chieftains rationally choose financial engineering—debt-financed share buybacks, for example—over capital investment in property, plants and equipment. Financial markets reward shareholder activism. Institutional investors extend their risk parameters to beat their benchmarks. And retail investors belatedly participate in the rising asset-price environment. All of this lifts balance-sheet wealth, at least for a while. But real economic growth—averaging just a bit above 2% for the fifth year in a row—remains sorely lacking. Higher asset prices are not translating into meaningful increases in capital expenditures, and the weak growth in business investment is proving to be an opportunity-killer for workers. Those with jobs have some job security. But they are less willing to run the risk of finding a better opportunity, or negotiating for higher wages. Those without jobs, especially in the younger cohorts without a post-high school education, do not attach to the workforce, thus never gaining the entry-level skills and discipline to build a career. The malaise in the labor markets—and muted business investment—help explain why productivity measures are a full percentage point below historical norms. The Fed's latest forecast has the economy growing above 3% during the balance of this year and next, and the unemployment rate falling to about 5.5% by the end of 2015. If the Fed's sanguine scenario finally comes to pass, interest rates are likely to move meaningfully higher across the yield curve. The money pouring into the financial markets may be redirected, in part, to the real economy. Stocks, leveraged loans and real estate are likely to re-price in a higher interest-rate environment. If rates move quickly or unexpectedly, the vaunted balance-sheet recovery could suffer a blow. What if there is an unexpected shock that causes the economy to slow in the next year or two? The Fed would surely be called upon to bolster asset prices and stimulate the real economy. But would a return to $85 billion per month of bond-buying really be effective? We are skeptical that either Wall Street or Main Street would be comforted by quantitative-easing redux. Balance-sheet wealth is sustainable only when it comes from earned success, not government fiat. Wealth creation comes from strong, sustainable growth that turns a proper mix of labor, capital and know-how into productivity, productivity into labor income, income into savings, savings into capital, capital into investment, and investment into asset appreciation. The country needs an exit from the 2% growth trap. There are no short-cuts through Fed-engineered balance-sheet wealth creation. The sooner and more predictably the Fed exits its extraordinary monetary accommodation, the sooner businesses can get back to business and labor can get back to work. What is the difference between 2% growth and 3% growth in the U.S. economy? As the late economist Herb Stein recounted, the answer is 50%. And the real difference is one between a balance-sheet recovery that helps the well-to-do and an income-statement recovery that advances the interests of all Americans. By John Mauldin | June 14, 2014 “How did you go bankrupt?” One of the many luxuries that my readers have afforded me over the years is their willingness to allow me to explore a wide variety of topics. Not all writers are so blessed, and their output and responses to it tend to stay focused on specific, often quite narrow topics. While this approach allows them to dig very deep into particular subject matter, it can reduce the total scope of their research, vision, and advice. But don’t get me wrong; these types of letters are very important. I benefit greatly from being a subscriber to a number of letters that give me detailed analysis for which I simply don’t have the time to do the research. There’s just too much going on in the world today for any of us to be an expert in more than a few areas.

I seem to find the most enjoyment and elicit the best response when I try to give my readers the benefit of my broad scope of reading and research as I try to figure out how all the various and sundry pieces of the puzzle fit together. For me, the world is just that: a vast and very complex puzzle. Trying to discern the grand themes and detailed patterns as the very pieces of the puzzle go on changing shape before my eyes is quite a challenge. To try to figure out which puzzle pieces are going to have the most influence and impact in our immediate future, as opposed to languishing in the background, can be a frustrating experience. I often find myself writing about topics (such as a coming subprime crisis or recession) long before they manifest themselves. But I think it is important to see opportunities and problems brewing as far in advance as we can so that we can thoughtfully position ourselves and our portfolios to take advantage. Today I offer some musings on what I’ve come to think of as the Age of Transformation (which I have been thinking about a lot while in Tuscany). I believe there are multiple and rapidly accelerating changes happening simultaneously (if you can think of 10 years as simultaneously) that are going to transform our social structures, our investment portfolios, and our personal futures. We have had such transformations in the past. The rise of the nation state, the steam engine, electricity, the advent of the social safety net, the personal computer, the internet, and the collapse of communism are just a few of the dozens of profound changes that have transformed the world in which we live. Therefore, in one sense, these periods of transformation are nothing new. I think the difference today, however, is going to be the simultaneous nature of multiple transformational trends playing out within a very short period of time (relatively speaking) and at an accelerating rate. It is self-evident that failure to adapt to transformational trends will consign a business or a society to the ash can of history. Our history and business books are littered with thousands of such failures. I think we are entering one of those periods when failing to pay close attention to the changes going on around you could prove decidedly problematical for your portfolio and fatal to your business. This week we’re going to develop a very high-level perspective on the Age of Transformation. In the coming years we will do a deep dive into various aspects of it, as this letter always has. But I think it will be very helpful for you to understand the larger picture of what is happening so that you can put specific developments into context – and, hopefully, let them work for you rather than against you. We’re going to explore two broad themes, neither of which will be strange to readers of this letter. The first transformational theme that I see is the emerging failure of multiple major governments around the world to fulfill the promises they have made to their citizens. We have seen these failures at various times in recent years in “developed countries”; and while they may not have impacted the whole world, they were quite traumatic for the citizens involved. I’m thinking, for instance, of Canada and Sweden in the early ’90s. Both ran up enormous debts and had to restructure their social commitments. Talk to people who were involved in making those changes happen, and you can still see some 20 years later how painful that process was. When there are no good choices, someone has to make the hard ones. I think similar challenges are already developing throughout Europe and in Japan and China, and will probably hit the United States by the end of this decade. While each country will deal with its own crisis differently, these crises are going to severely impact social structures and economies not just nationally but globally. Taken together, I think these emerging developments will be bigger in scope and impact than the credit crisis of 2008. While each country’s crisis may seemingly have a different cause, the problems stem largely from the inability of governments to pay for promised retirement and health benefits while meeting all the other obligations of government. Whether that inability is due to demographic problems, fiscal irresponsibility, unduly high tax burdens, sclerotic labor laws, or a lack of growth due to bureaucratic restraints, the results will be the same. Debts are going to have to be “rationalized” (an economic euphemism for default), and promises are going to have to be painfully adjusted. The adjustments will not seem fair and will give rise to a great deal of societal Sturm und Drang, but at the end of the process I believe the world will be much better off. Going through the coming period is, however, going to be challenging. “How did you go bankrupt?” asked Hemingway’s protagonist. “Gradually,” was the answer, “and then all at once.” European governments are going bankrupt gradually, and then we will have that infamous Bang! moment when it seems to happen all at once. Bond markets will rebel, interest rates will skyrocket, and governments will be unable to meet their obligations. Japan is trying to forestall their moment with the most breathtaking quantitative easing scheme in the history of the world, electing to devalue their currency as the primary way to cope. The US has a window of time in which it will still be possible to deal with its problems (and I am hopeful that we can), but without structural reform of our entitlement programs we will go the way of Europe and numerous other countries before us. The actual path that any of the countries will take (with the exception of Japan, whose path is now clear) is open for boisterous debate, but the longer there is inaction, the more disastrous the remaining available choices will be. If you think the Greek problem is solved (or the Spanish or the Italian or the Portuguese one), you are not paying attention. Greece will clearly default again. The “solutions” have so far produced outright depressions in these countries. What happens when France and Germany are forced to reconcile their own internal and joint imbalances? The adjustment will change consumption patterns and seriously impact the flow of capital and the global flow of goods. This breaking wave of economic changes will not be the end of the world, of course – one way or another we’ll survive. But how you, your family, and your businesses are positioned to deal with the crisis will have a great deal to do with the manner in which you survive. We are not just cogs in a vast machine turning to powers we cannot control. If we properly prepare, we can do more than merely “survive.” But achieving that means you’re going to have to rely more on your own resources and ingenuity and less on governments. If you find yourself in a position where you are dependent upon the government for your personal situation, you might not be happy. This is not something that is going to happen all of a sudden next week, but it is going to unfold through various stages in various countries; and given the global nature of commerce and finance, as the song says, “There is no place to run and no place to hide.” You will be for ced to adjust, either in a thoughtful and premeditated way or in a panicked and frustrated one. You choose. I should add a note to those of my readers who think, “I don’t have to worry about all this because I am not dependent on Social Security.” Wrong. A significant majority of the retiring generation does depend on Social Security and also on government-controlled healthcare, and their reactions and votes and consumption patterns will have an impact on society. Ditto for France, Germany, Italy, and the rest of Europe. The Japanese have evidently made their choice as to how to deal with their crisis. If you are a Japanese citizen and are not making preparations for a significant change in your national balance sheet and the value of your currency, you have your head in the sand. There’s no question that the reactions of the various governments as they try to forestall the inevitable and manage the crisis will create turmoil and a great deal of volatility in the markets. We have not seen the last of QE in the US, but Japan is going gangbusters with it, and it is getting fired up in Europe and China. Most people in most places will attempt to ignore the transformational wave barreling at them. After all, aren’t bond rates in Europe lower than ever? Indeed, French and Spanish bond yields are at their lowest levels since the 1700s, believe it or not. Isn’t the market telling us there isn’t a problem? If Japan is such a problem, shouldn’t the yen be going into the toilet by now? The US deficit is shrinking, and government spending is actually falling. Seems like the problems have all gone away. But the problems I’m thinking about are not ones that will manifest themselves this week. The markets did not foresee the 2008 credit crisis or the last two recessions or the European crisis, even just a few months before they hit. When the world doesn’t come to an end as predicted (and there were plenty of prognostications of utter doom last decade), we seem to get complacent and ignore the basic arithmetic that you have to have more income than you have expenditures, and to conveniently forget that debt, even at low interest rates, is compounding. And yes, it is possible to grow your way out of the problem – but only if you have real growth. Now, much of the world is structurally challenged in such a way that structural imbalances inhibit growth at the rate necessary to significantly put a dent in swelling debt levels. keep reading here June 10, 2014 By Barry Ritholtz Bloomberg.net Each morning, I go through a similar routine: I wake up (no alarm clock), go to the kitchen to get a cup of coffee (this is my machine of choice lately), launch a script that opens 40 or so Firefox tabs. As part of my morning research, I quickly scan this series of websites to see what happened overnight, and what might be interesting. Part of that list is Jason Zweig’s "This Day in Financial History,'' which led to this morning’s gem: Today in 1997: The Dow Jones Industrial Average closes above 7,500 for the first time, and The Wall Street Journal notes that the market’s climb ‘seems to inspire equal parts awe and dread among many investors.’ Fred Taylor, CIO at U.S. Trust, guesses that the stock market will end the year ‘lower than its current level.’ (The Dow finishes 1997 at 7908.25, or more than 5% higher.) Which leads to today’s question: Why is calling a top so much more challenging than seeing a market bottom?

I don’t think many traders would disagree with that notion. It is often said that “Tops are a process while market bottoms are an event.” Or as Michael Batnick observed, “Bull market tops are more difficult to call than bear market bottoms because doubt is a far more resilient emotion than hope.” Allow me to rephrase that without any of the lovely subtlety I am known for: The dominant emotion at bottoms is fear -- a palpable and very recognizable state. Tops on the other hand, come about through the combination of greed, complacency and indifference. This is a much more challenging set of factors to identify. Indifference does not cause a huge spike in VIX, a standard measure of market volatility; volume does not increase as traders become complacent. There are many other forces at play: Risk aversion: This plays a large part in the differences between tops and bottoms. After a market drops 25 percent or more, the recency effect weighs heavily on investors. We dread losses at about twice the rate that we desire gains. That asymmetry leads to a variety of investing behaviors. Because of this, we feel the losses of the big 2008-09 crash more intensely than we feel the gains of the 2009-2014 rally. Biased perspective: Anyone with an investment in the market has a bias. It isn't a good or a bad thing; it simply is the way you are wired. Most investors who are long equities expect the market to go higher. Those who are out of equities, or (heaven forbid, short) believe that stocks will go lower. Hence, these market calls often reflect investors talking their book. I was reminded yesterday of an old joke about bubbles, as Art Hogan noted: “An asset bubble is an asset that is rising, that you have not invested in.” Not rigorous: Most of the calls for a market top in this cycle haven't been very rigorous. Lots of gut feelings, sensations, and instincts, which history teaches us are a surefire way to lose money in markets. Contrast that with the analysis that Paul Desmond employs, using quantifiable metrics. That is a very different approach than merely guessing. Fear is more visible than greed: During crashes, lots of metrics light up. I can give you a list of technical and sentiment measures that all pin the needle during a crash. On the other hand, the view from tops is much more nuanced. No downside for pundits: Making a big splashy forecast almost guarantees calls from news media producers and naïve reporters. If by some stroke of luck, a talking head gets it right, it makes his career. On the other hand, few remember that wildly wrong money-losing call made on TV. Quick, name the person who said five years ago that hyperinflation would be the result of QE. Who noted a 1987 like crash was imminent every year over the past four years? Which pundit forecast gold at $5,000 an ounce?1 You don’t remember those calls because an endless stream of bad forecasts crosses your desk every day. The future is unknown: The world is a complex place. Most people really don't understand what has already happened. We have a loose understanding of recent events, but we are far less informed than we believe. Discerning what is going to happen is an almost impossible task. The bottom line is that these market calls are at best one part art, one part science. Whatever market calls people choose to make (or follow) it helps to understand this: No one is infallible, most are pretty bad, few are consistent. Luck plays a huge part as well. Even those who occasionally get it right are no more likely to continue that streak than anyone else. I have no idea when this market will reach a top; it could have been yesterday for all I know. But I can tell you that if your investing process is highly dependent on correctly identifying when a market is about to top and reverse, I expect you will need new investment plan eventually. By Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

The Telegraph - 4 June 2014 The way we are going, the whole world will end up with zero interest rates or some variant of quantitative easing before long. Such is the overwhelming power of deflation in countries with burst credit bubbles. Such too is the implication of a global savings rate that has spiralled to an all-time high of 25pc of GDP, starving the world of demand. The European Central Bank looks poised to cut the discount rate below zero on Thursday, becoming the first of the monetary superpowers to venture into these uncharted waters. Banks will be charged to park money in Frankfurt. More than €800bn of money market funds will sink below the water line, so the funds will go elsewhere. The chief purpose is to drive down the euro, an attempt to pass the toxic parcel of incipient deflation to somebody else. The ECB is expected to map out future purchases of asset-back securities, "unsterilised" and intended to steer stimulus with surgical precision towards small businesses in what amounts to light QE. This is not yet the €1 trillion blitz already modelled and sitting in the ECB's contingency drawer. Germany's DIW institute is calling for €60bn of bond purchases each month, equal to 0.7pc of total EMU sovereign debt, and roughly in line with moves by the US Federal Reserve. Such radical action will have to wait. In China the new talk is "targeted monetary easing", with the first hints of outright asset purchases. Railways bonds have been cited, and local government debt. The authorities are casting around for ways to keep the economy afloat while at the same gently deflating a property boom that has pushed total credit from $9 trillion to $25 trillion in five years. This is not an easy task, not least because land sales and taxes make up 39pc of state revenue in China, and the property sector employs 20pc of workers one way or another. It is clearly a bubble of epic proportions, and already losing air. Mao Daqing from Vanke - China's top developer - says total land value in Beijing has been bid up to such extremes that is on paper worth 61.6pc of America's GDP. The figure was 63.3pc for Tokyo at the peak of the bubble in 1990. "A dangerous level," he says. China faces this delicate task with deflation lodging in the economic supply chain. Factory gate inflation is -2pc, with prices falling for 27 months. It has no safety buffer against a shock, and is facing demographic headwinds. The workforce has already peaked and is now shrinking by 3m a year, much like the squeeze that played such a big role in the onset of Japan's deflation. The question is why the world economy cannot seem to shake off this "lowflation" malaise, even after QE on unprecedented scale by the US, Britain, Japan and in its own way Switzerland. America's core PCE inflation is still just 1.4pc five years after the Fed embarked on $3 trillion of bond purchases. Part of the reason is a glut of factories flooding the world with goods, bearing down on global prices. China's investment last year was $5 trillion, as much as in Europe and the US together. But another argument is taking hold, which I pass on to readers though it is not my view. Narayana Kocherlakota, the Minneapolis Fed chief, suggested as far back as 2011 that zero rates and QE may perversely be the cause of deflation, not the cure that everybody thought. This caused consternation, and he quickly retreated. Stephen Williamson, from the St Louis Fed, picked up the refrain last November in a paper entitled "Liquidity Premia and the Monetary Policy Trap", arguing that that the Fed's actions are pulling down the "liquidity premium" on government bonds (by buying so many). This in turn is pulling down inflation. The more the policy fails - he argues - the more the Fed doubles down, thinking it must do more. That too caused a storm. The theme refuses to go away. India's central bank chief, Raghuram Rajan, says QE is a beggar-thy-neighbour devaluation policy in thin disguise. The West's QE caused a flood of hot capital into emerging markets hunting for yield, stoking destructive booms that these countries could not easily control. The result was an interest rate regime that was too lax for the world as a whole, leaving even more economies in a mess than before as they too have to cope with post-bubble hangovers. The West ignored pleas for restraint at the time, then left these countries to fend for themselves. The lesson they have drawn is to tighten policy, hoard demand, hold down their currencies and keep building up foreign reserves as a safety buffer. The net effect is to perpetuate the "global savings glut" that has starved the world of demand, and that some say is the underlying of the cause of the long slump. "I fear that in a world with weak aggregate demand, we may be engaged in a futile competition for a greater share of it," he said. The Bank for International Settlements says the world is suffering from addiction to stimulus. "The result is expansionary in the short run but contractionary over the longer term. As policy-makers respond asymmetrically over successive financial cycles, hardly tightening or even easing during booms and easing aggressively and persistently during busts, they run out of ammunition and entrench instability. Low rates, paradoxically, validate themselves," it said. Claudio Borio, the BIS's chief economist, says this refusal to let the business cycle run its course and to purge bad debts is corrosive. The habit of turning on the liquidity spigot at the first hint of trouble leads to "time inconsistency". It steals growth and prosperity from the future, and pulls the interest rate structure far below its (Wicksellian) natural rate. "The risk is that the global economy may be in a deceptively stable disequilibrium," he said. Mr Borio worries what will happen when the next downturn hits. "So far, institutional set-ups have proved remarkably resilient to the huge shock of the Great Financial Crisis and its tumultuous aftermath. But could (they) withstand yet another shock?" he said. "There are troubling signs that globalisation may be in retreat. There is a risk of yet another epoch-defining and disruptive seismic shift in the underlying economic regimes. This would usher in an era of financial and trade protectionism. It has happened before, and it could happen again," he said. Masaaki Shirakawa, the former governor of the Bank of Japan, says wearily that the world might have learned something if it had studied QE in his country. The monetary base was doubled after 1997, yet deflation ground on. "We deployed all sorts of unconventional monetary policy measures ahead of other major central banks. Japan has been living in a world of zero interest rates for almost all of the past 15 years. The Bank of Japan hugely expanded its balance sheet, purchased non-traditional assets and adopted forward guidance on future policy," he said recently. "It is not an exaggeration to say that almost all the policies adopted by other central banks after the Great Financial Crisis, were policy measures which the Bank of Japan had “invented” much earlier, in uncharted waters, and without textbooks or precedents." Critics of course say the BoJ acted timidly, dabbling in QE. What it is doing now under Haruhiko Kuroda is entirely different, buying $75bn of bonds each month, much of it long-term debt outside the banking system that does most to boost the broad money supply. This has lifted Japan's inflation to 1.5pc, stripping out VAT rises. The great test will be whether this lasts as the sugar rush wears off, and whether it flows through into higher spending and wages, breaking the deflationary psychology once and for all. The evidence in Britain and America is that QE has had a potent effect, preventing double-dip recessions as fiscal austerity began to bite, in stark contrast to Europe. The story is not over, nor have the Fed and the Bank of England extricated themselves. The contraction of US GDP in the first quarter is a warning sign. Personally, I am not yet ready to accept the claim that QE is drawing the world deeper into deflation but the arguments cannot be dismissed lightly. If they are broadly correct, the case for such stimulus collapses. My view is closer to the monetarists who say Western central banks have brought this mess on themselves by concentrating all their zeal on interest rates, viewing QE merely as a tool to drive yields ever lower, even pledging to hold down them down for years through "forward guidance". The sin is Ben Bernanke's heresy of "creditism", ignoring three centuries of orthodoxy and the traditional quantity of money mechanism. What they should have done is to target M3 money growth of 5pc, or nominal GDP of 5pc, and let interest rates find their own level. Indeed, rates should naturally rise as recovery takes hold. Trying to force them down come what may is a formula for trouble. The BIS is absolutely right about that. Yet the ECB is about to make the same mistake, fiddling with interest rates rather than going to the heart of the monetary disorder. Such a policy is what Japan did for a decade and is likely to disappoint. If Europe is at risk of deflation, the proper response is a monetary barrage of such force that nobody can be in any possible doubt about the outcome. As Napoleon said, if you say you are going to take Vienna, then take Vienna. Rule No. 1: Do not venture in markets and products you do not understand. You will be a sitting duck.

Rule No. 2: The large hit you will take next will not resemble the one you took last. Do not listen to the consensus as to where the risks are (that is, risks shown by VAR). What will hurt you is what you expect the least. Rule No. 3: Believe half of what you read, none of what you hear. Never study a theory before doing your own observation and thinking. Read every piece of theoretical research you can-but stay a trader. An unguarded study of lower quantitative methods will rob you of your insight. Rule No. 4: Beware of the nonmarket-making traders who make a steady income-they tend to blow up. Traders with frequent losses might hurt you, but they are not likely to blow you up. Long volatility traders lose money most days of the week. Rule No. 5: The markets will follow the path to hurt the highest number of hedgers. The best hedges are those you alone put on. Rule No. 6: Never let a day go by without studying the changes in the prices of all available trading instruments. You will build an instinctive inference that is more powerful than conventional statistics. Rule No. 7: The greatest inferential mistake: “This event never happens in my market.” Most of what never happened before in one market has happened in another. The fact that someone never died before does not make him immortal Rule No. 8: Never cross a river because it is on average 4 feet deep. Rule No. 9: Read every book by traders to study where they lost money. You will learn nothing relevant from their profits (the markets adjust). You will learn from their losses. Nassim Taleb and Mark Spitznagel talk about how government intervention postpones the inevitable

By Nassim Taleb & Mark Spitznagel May 31, 2014 4:00 AM Mark Spitznagel and Nassim Taleb started the first equity tail-hedging firm in 1999. Since then these two friends and colleagues have helped popularize so-called “black swan” investing, with Spitznagel as the founder and CIO of hedge fund Universa Investments and Taleb as an academic and author of The Black Swan. The two men recently sat down to discuss Spitznagel’s new book, The Dao of Capital, as well as their reactions to and criticisms of Thomas Piketty’s book, i. Here is a transcript of their conversation: Nassim Taleb: Mark, your book is the only place that understands crashes as natural equalizers. In the context of today’s raging debates on inequality, do you believe that the natural mechanism of bringing equality — or, at the least, the weakening of the privileged — is via crashes? Mark Spitznagel: Well straight away let’s ask ourselves: Are we really seeking realized financial equality? How can we ever know what is the natural or acceptable level of inequality, and why is it even the rule of the majority to determine that? That aside, one can absolutely say logically and empirically that asset-market crashes diminish inequality. They are a natural mechanism for this, and a cathartic response to central banks’ manipulation of interest rates and resulting asset-market inflation, as well as other government bailouts, that so amplify inequality in the first place. So crashes are capitalism’s homeostatic mechanism at work to right a distorted system. We are in this ridiculous situation where utopian government policies meant to lessen inequality are a reaction to the consequences of other government policies — a round trip of market distortion. After we’ve been run over by a car, the assumed best treatment is to back the car over us again. Taleb: I see you are distinguishing between equality of outcome and equality of process. Actually one can argue that the system should ensure downward mobility, something much more important than upward one. The statist French system has no downward mobility for the elite. In natural settings, the rich are more fragile than the middle class and we need the system to maintain it. The reason I am discussing that here is linked to your book, The Dao of Capital, which mixes (rather, unifies) personal risk-taking with explanations of global phenomena. But as an author I hate people’s summaries of my work. Can you provide your own summary in a paragraph? Spitznagel: To your first point, yes exactly, and in fact what’s hidden beneath all the aggregate income-inequality data is much cross-sectional downward mobility, in that most people in the right tail of income spend very little time there. The transience of success is assured by natural entrepreneurial capitalism, and is precisely what works about it: unseating the top, driving out the lucky and unworthy. Without this dynamic, capitalism doesn’t work. It isn’t even capitalism, but rather oligarchic central planning. Yet modern government chips away at this dynamic in so many ways, most significantly by providing floors and safety nets to crony bankers and other financial punters. What irony that the same people who today loudly endorse a global wealth tax to rein in inequality were also the very ones saying guys like us were nuts for opposing the bailouts back in 2008! That we so casually ignore the implications of this goes to the main point of my book: In the words of Bastiat, we pursue a small present good which will be followed by a great evil to come, rather than a great good to come at the risk of a small present evil. The latter is what I call roundaboutness, which is central to strategic decision making, especially investing. It is about counter-intuitively heading right in order to better go left, or taking small losses now — and willingly looking like an idiot — to build a strategic advantage for later. In Daoism it is wei wuwei or shi. In economics it is Robinson Crusoe, who starves himself by not spending all his time fishing by hand and instead spends time making a boat and net, in order to catch many more fish later. We have roundaboutness to thank for civilization itself. Yet it is so difficult because of our myopic brain, and in most modern instances downright impossible because of our myopic social structures — Washington and Wall Street being the best examples, where to disappoint in the present means there is no future, so why be concerned with the future? Of course exploiting this is what we do as investors. Looking at markets in this way, specifically how they scorn the roundabout — thanks in no small part to the Federal Reserve — is to understand them better, particularly the traps that they set. Taleb: Did you consider simple remedies such as decentralization? Spitznagel: When you understand the problem of centralized power in general, then the specific problem of central banking is just a particular example. What more centralized economic authority is there than the manipulation of money? And this feeds into greater and greater centralized authority. Bureaucrats and politicians, for the same reasons as Wall Street traders, are necessarily anti-roundabout. Decentralization dissipates their influence and limits their reach. Small localized majorities can do just as stupid and myopic things as broad majorities, but their coercion is escapable and weaker, and they can transparently fail and try again. (James Madison didn’t get this.) With public decentralization naturally comes private decentralization as, without public intervention, the bigger and broader the private bungle the more likely the disappearance of the bungler. Taleb: I agree, but we need a “negative state” for law enforcement, something like the U.S. federal state or the traditional empire during Pax Romana or Pax Ottomana. In this idea the role of the state is protection, not to promote education or, say, corn fructose, which we know have worse adverse consequences when coming top-down from a powerful centralizer and, hence, implemented at a large scale. In my work the central mission of the state is to protect the environment, to shield me from irreversible harm done to my backyard by people who don’t have skin in the game and are protected by limited liability. There are things that can be done by the state, and only the central state. Do you agree? Spitznagel: I definitely agree that the only conception of the state that makes any sense is the “night watchman” variety, which exists only to enforce the rules of the game rather than trying to pick the winners and losers (whether it’s financial institutions or monoculture crops). There is a deep tradition in classical liberalism and modern libertarianism that stresses the importance of limiting government action to the defense of life and limb — a defense of “negative liberty” — rather than the “positive” conception where it is the job of the government to promote literacy, full employment, equality, and so forth. Even protecting the environment falls under this “negative liberty” — pollution should really be seen as an aggression against property (as in one’s lungs, for instance). Even as recently as the 19th century pollution was a tort, suable for damages and to cease and desist. Then the law morphed to permit what was considered non-anomalous polluting. Ironically, it was paternalistic state oversight that trumped the decentralized and allegedly myopic common-law tradition — where an individual household could “halt progress” by bringing an injunction against the factory upstream that is dumping chemicals into the river. The rights of small property owners were set aside in the quest for industrial growth. In any event, your approach of asking the state — the ultimate agency that lacks skin in the game (central banks being the greatest example) — to protect us from those lacking skin in the game is asking a lot of it. How do you justify your generalized skin-in-the-game criterion with the observation that many of history’s greatest calamities — from military to financial — have basically been done at the hands of those whose skin was very much in the game? For example, we can’t blame the inadequacy of the Maginot Line and other French defenses on the lack of skin in the game; presumably the French officials responsible for these blunders suffered very great personal distress from the German invasion. And then there’s the crazy Nazi leaders, all of whom had an enormous stake in the outcome of their decisions. Certainly in finance, many a blow-up ruined those responsible. Taleb: The skin-in-the-game idea, or what I now call the silver rule, i.e., the negative golden rule, is necessary but not sufficient. And it is not literal, as it can be gamed. Talking about the silver rule, I feel that the clique of academic economists and people who spent too much time without contact with reality via risk-taking (that’s the main epistemological benefit of skin in the hogame), these people are now engaging in the politics of envy. The real class war we have isn’t what Marx thought it was, between the proletariat and the owners of capital. It is between the policy-makers-bureaucrats-with-no-skin-in-the-game who want to tax the rich to increase their power and the other classes. Historically, we have known since the Romans that the enemies of the people were the senatorial class, not the emperor. Bureaucracies are metastatic. Those economically in the bottom half are not interested in the rich getting poorer, they want a better life and hope to rise should they want to. And economists can come up with any economic theory that fits them. They can embrace any narrative-with-data that increases their role. Having seen economists with data-mined theories blow up left and right, what do you think of Piketty’s book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, and how do you compare it with yours? Spitznagel: Well, while some have recently and rightfully criticized Piketty’s cherry-picked data and other empirical defects, to me his principal problems are conceptual — specifically his reliance on a very fast-and-loose model of what capital is and how it contributes to the economy. In his book, he switches back and forth between two distinct meanings for “capital”: Sometimes it’s an indiscriminate blob of concrete physical things — machinery, tools, acres of farmland — and other times it’s a sum of money. He then relies on a very crude model in which the stock of capital combines with the stock of labor to yield a blob of output, which is divided among the two classes according to a few parameters. With this confused structure and some historical trends, Piketty forecasts that the owners of “capital” will grow increasingly dominant, hence his call for a punitive tax on wealth for those with the most. There are several problems with this approach. First and most basic, by constantly flipping back and forth between his concepts of capital, Piketty falls prey to crude, basic fallacies that have long ago been dismissed. The Austrian economist Böhm-Bawerk picked them apart in the late 1800s! In particular, Böhm-Bawerk showed that the physical productivity of a capital good can explain its rental price — how many dollars it earns per hour of hire — but has nothing directly to do with the rate of return the capitalist earns by investing in the physical-capital good. (This objection isn’t unique to the free-market Austrians, but is even embraced by post-Keynesians today.) Another major problem, of course, is the sheer envy underlying the whole enterprise. So what if capitalists enjoy a growing share of “total income”? The more tools and equipment that the workers have to augment their labor power, the higher real wages will be in absolute terms. Even if Piketty’s diagnosis were correct, his solution would hurt workers and capitalists alike. Most severe of all is that his very cartoonish and academic concept of capital just doesn’t allow for the monetary distortions and consequent booms and busts we’ve seen. It takes a richer framework than Piketty’s to show how this works. His theorizing blinds him to the most obvious empirical relationship in his own data: his historical high-inequality periods perfectly coincide with the two greatest monetary-induced-bbubble and crony-capitalism periods — 1929 and now. As for my book, I deal with the world largely shaped by Piketty’s same naïve concept of capital. By manipulating interest rates, central planners magically appear to manipulate capital’s profitability, and hence all the many moving parts and agents of the economy are but another tool to create the economy that they want. Of course, the world just isn’t that clean and simple. When we look back at Böhm-Bawerk’s notion of Produktionsumweg (or “roundabout production,” the essence of economic growth), we can recognize how far modern economics has now strayed from the multidimensional complexities of reality. Economics and investing have become games of cavalier manipulation and side bets on direct ends rather than what they should be: disciplines of understanding (what Mises called Verstehen) and building productive means. So I think it is very important to change our perception of these things. For me, this mostly happened in my youthful pit-trading days — a formative experience you and I share in common. As I address in my book, investors who understand the dynamics of economic distortions are far better at profiting from them. Taleb: Let’s generalize from the Piketty into the “macro BS” problem. I started as a foreign-exchange option trader. Thirty years ago economists believed that “purchasing power parity” determined the “long term” currency rate between countries. And economists who became traders kept blowing up by selling the “expensive” currency and buying the “cheap” one. And, if anything, the opposite held: Currencies that were expensive kept getting more expensive. So it became known that the fastest road to bankruptcy in foreign exchange was an economics degree. More analytically, saying “the long term” without attaching a period to it (six months, six years, six hundred years, etc.) is meaningless. The duration is more relevant than the idea that currencies “converge.” In the Piketty case, the argument that the rate of growth and that of the return on capital ought to be equal “in the long term” is very similar. Except that, in addition, Piketty forgot to make them stochastic, which would skew the return on capital by adding a small probability of ruin “Black Swan”-style that would annihilate capital in the long run. Which bring me to silver rule (skin-in-the-game) problem. Every person who has skin in the game knows sort of what is bullsh** and what is not, since our capacities to rationalize — and those of bureaucrats and economists — are way too narrow for the complexity of the world we face, with its complex interactions. And survival is a stamp of statistical validity, not rationalization. This, in short, is why we are now talking about your book, because a book with “skin” is a different animal. So tell us about your idea of an impending “fixing” of the system, so to speak — how reality will resolve the current contradictions. Spitznagel: I see the whole “r>g” [meaning return on capital is greater than the rate of growth] thing as taking bubble observations and rationalizing their extrapolation forever, thus simultaneously neglecting both the incidence of asset bubbles and what’s so bad about them. Such enormous shortsighted errors follow from the noisy duration of the “long term.” And exploiting these errors is the name of the game. In everyone’s scorn of the roundabout lies its greatest edge. The main metaphor of my book is the “Yellowstone effect”: A massive fire in Yellowstone Park in 1988 opened the eyes of foresters to the fact that a century of wildfire-suppression, and with it competition- and turnover-suppression, had only delayed, concentrated, and by far worsened the destruction — not prevented it. This isn’t just about dead-wood accumulation creating a fragile tinderbox network. The real issue is how our tinkering artificially short-circuits the fundamental capacity of the system to allocate its limited resources, correct its errors, and find its own balance through the internal communication of information that no forestry manager could ever possibly possess. (The more this is mocked by technocratic naïfs like Geithner, the more valid it is.) But that capacity is still there, and homeostasis ultimately wins through a raging inferno. This is a cautionary tale for our economy. A crash, or the liquidation of assets that have grown unimpeded by economic reality (as if there were more nutrients in the ecosystem than there actually are), looks to academics and bureaucrats — and just about everyone else as well — like the system breaking down. It is actually the system fixing itself. Taleb: Let us each conclude here. For my part, I would say three things. First that intervention — in general, whether medical, governmental, or other — has side effects and needs to be treated exactly as we do with other complex systems: only when extremely necessary. Second, counter to naïve conservatism, nature is not conservative, it destroys and creates species every day, but it does so in a certain pattern: Its destruction has the effect of isolating the system from large-scale harm. It does not try to preserve the past; it only tries to preserve the system. Finally, liberty is not an economic good, but an existential one. The economic good is a mere bonus. The argument that liberty is good for economic activity or for growth of the system feels lowly and commercial (an argument used by consequentialists). If you were a wild animal, would you elect to be in a zoo because the economy is better over there than in the wild? Liberty is my raison d’être. Spitznagel: Yes. The Daoist scholar Zhuangzi once said, upon being offered the prime ministership about 2,500 years ago, “Would the dead and adorned turtle in the king’s palace not prefer to be alive and free in the mud? So too would I.” Here’s how I would reconcile my own position with yours: I agree that liberty is an end in itself, and is not to be valued merely as an instrumental means to something else. But precisely because of that, even if hypothetically you could convince me that a certain government intervention in the market were extremely necessary, as you say — for instance, would likely lead to greater economic growth or lower unemployment — I would still reject it on principle, because my support for property rights and a sphere of individual autonomy free from political meddling is not ultimately based on a utilitarian criterion. By all means, let’s brainstorm and see if there are ways to alleviate these problems and provide relief to the suffering. But any proposal that involves using coercion on unwilling citizens should be off the table. Anything else is a slippery slope to what we have today from these serial crises. To say this by no means demonstrates that I’m an ideologue or unscientific. What we get from this is a self-organization that often seems chaotic to our myopic eye, yet when we take a step back we can see how the ecosystem ultimately and optimally steers itself. It was Zhuangzi, as I discuss in my book, who first articulated this idea of spontaneous order — whereby order naturally emerges from bottom-up individual interactions when things are left alone rather than from top-down control — a concept developed later by Menger and Hayek. We live in an economic age where we’ve simply lost our ability to look at the world in this way, though I suspect we’ll be reminded of it again sooner rather than later. Perhaps our takeaway from economic crises will finally be different the next time around. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed