|

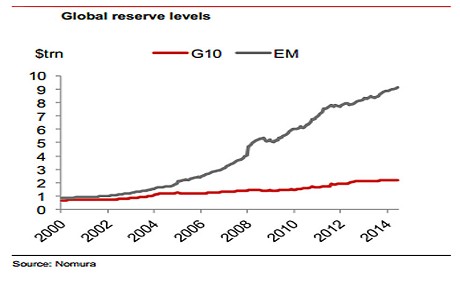

By Ambrose Evans-Pritchard 30 July, 2014 The spigot of global reserve stimulus is slowing to a trickle. The world's central banks have cut their purchases of foreign bonds by two-thirds since late last year. China has cut by three-quarters. These purchases have been a powerful form of global quantitative easing over the past 15 years, driven by the commodity bloc and the rising powers of Asia. They have fed demand for US Treasuries, Bunds and Gilts, as well as French, Dutch, Japanese, Canadian and Australian bonds and parastatal debt, displacing the better part of $12 trillion into everything else in a universal search for yield. Any reversal would threaten to squeeze money back out again. Jens Nordvig, from Nomura, said net foreign reserve accumulation by central banks fell to $63bn in the second quarter of this year, from $89bn in the first quarter, and $181bn in the fourth quarter of 2013. These data are adjusted for currency swings, and are fresher than the delayed figures published by the International Monetary Fund. "There are major shifts going on global capital markets. People have been lulled into a false sense of security by low volatility and they haven't paid attention. We're not seeing any risk aversion in financial markets," he said. The world superpower in this game is China, with reserves just shy of $4 trillion. Mr Nordvig estimates that China's purchases dropped to $27bn in the last quarter, down from $106bn in the preceding quarter. This looks like a permanent shift in policy. Premier Li Keqiang said in May that the reserves had become a "big burden" and were doing more harm than good, playing havoc with monetary policy, as global economists have been warning for a long time. China's policy of holding down the yuan for mercantilist trade advantage caused it to import excess stimulus from America at the wrong moment in its own cycle, causing China's credit boom to go parabolic as loans rose from $9 trillion to $25 trillion in five years. Russia is drawing down on its $480bn reserves for an entirely different reason. The central bank has run through $40bn since the Ukraine crisis erupted as it tries to shore up the rouble. This is surely going to get worse as Western sanctions bite in earnest, shutting energy companies and banks out of global capital markets. The central bank has already flagged it will step in to help companies roll over foreign debt, maturing at a rate of $10bn a month. The European Commission stated openly in a leaked briefing paper last week that the aim of the funding freeze for Russian banks is to force them into the arms of the state, bleeding the Kremlin coffers. The implication of the global reserve data is that this form of QE is being run down just as the US Federal Reserve runs down its own QE by tapering bond purchases, and then prepares to tighten. The global central banks have been buying around $250bn of bonds a month in one form or another for most of the past three years. This is being cut to a fraction. Global reserve accumulation works like QE by the Fed, which openly admits that the purpose is to drive up asset prices, and thereby ignite the kindling wood of recovery. But the global variant has been much larger, soaring from 5pc to 13pc of world GDP since 2000. Edwin Truman, from the Peterson Institute in Washington, says the figure is nearer 22pc - or $16.2 trillion - if sovereign wealth funds are included. This has been a wall of money pushing into asset markets, part of what former Fed chief Ben Bernanke called the "Asian savings glut". You could argue that these reserves and quasi-reserves were the biggest single cause of the worldwide credit bubble before the system blew up in 2008. They are one reason for the "puzzling disconnect between the markets’ buoyancy and underlying economic developments globally" that we are seeing now, to cite the Bank for International Settlements. It is remarkable that global equity markets have been surging this year even though world trade has been sputtering, and actually contracted by 0.6pc in May, according to the Dutch CPB World Trade Monitor. This is the triumph of excess global capital over the real economy, and by implication a victory for shareholders and property owners over workers and wage-earners. If it is true that reserve accumulation causes asset bubbles and dangerous carry trades of every kind - as suggested in a series of IMF papers - then any sign that it is slowing and might even be going into reverse ought to be a cautionary warning. We had a taste of this in the Great Recession when emerging markets suddenly began to liquidate reserves to defend their currencies, causing a liquidity crunch that compounded the global crisis. These reserve figures are opaque and difficult to interpret. A recent survey of central banks, wealth funds and government pension funds by the monetary forum OMFIF estimated that they have $29 trillion invested in global markets, and that they too have joined the scramble for yield. The study said the Chinese central bank, PBOC, and others had become "major players on world equity markets", effectively fuelling stock bubbles in much the same way they previously fuelled credit bubbles. "It appears that PBOC itself has been directly buying minority equity stakes in important European companies," it said.

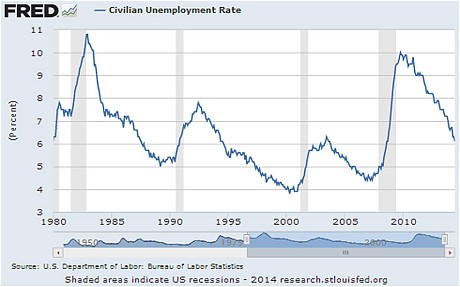

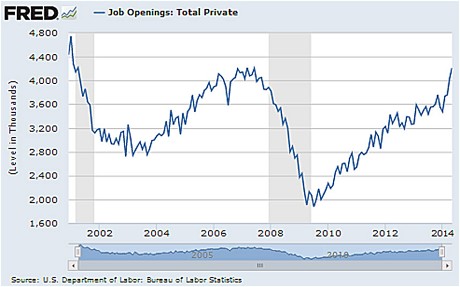

It is possible that central banks are simply rotating from bonds into equities, deemed less vulnerable to a bond sell-off if inflation picks up again. Mr Nordvig said Nomura's data capture all of the flows and these show that pace is slowing. "I would miss it only if the money was being funnelled into a secret sovereign wealth fund," he said. Some hope the European Central Bank will pick up the baton as the Fed bows out, launching QE on a comparable global scale. They are counting on a seemless transition. Yet the ECB will act only if forced to do so by deflationary shocks, and even then without conviction, like the tentative thrusts of the Bank of Japan in the pre-Abe era. Political resistance in Germany is paralysing. Besides, the long-feared moment of Fed tightening is drawing much closer. US unemployment has already dropped to 6.1pc, 14 months earlier than the Fed expected. The US is near the "NAIRU" moment when labour shortages cause wage-price pressures. We are entering a treacherous phase when the central bank fraternity is switching sides, for various reasons, knocking away a central prop of the asset edifice. In theory this is exactly what should happen. Economic gains may be driven once again by technology, not by artifice. The savings glut may melt slowly into real demand. Yet it would surely be a miracle if we can extract ourselves so easily from an unprecedented experiment over the 15 years that has driven total debt ratios to a record 275pc of GDP in the rich states, and a record 175pc in emerging markets. The whole world is leveraged to the slightest error now made by central banks. Tapering Is Now Tightening

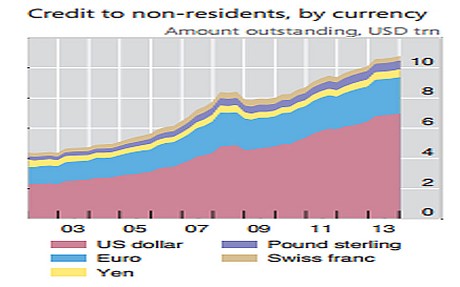

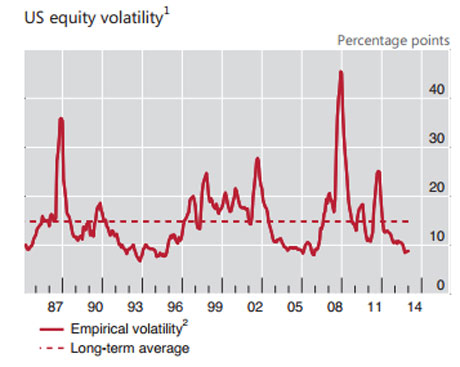

by David R. Kotok, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer 19 July, 2014 For a long time, as we saw it, tapering and the threat of tapering (as in last year’s taper tantrum) did not constitute tightening. Today we explore why we believe the situation has now changed. In order to understand why tapering was not tightening initially, we must momentarily set aside all influences on US Treasury note and bond interest rates that fall outside of the Federal Reserve’s program. Pretend for a minute that foreign exchange flows, geopolitical risks, inflation expectations, deflation expectations, sovereign debt biases, preferred habitat buyers, and a million other things are all neutral. They never are, but for this exercise pretend that they are so. We have observed and commented on QE and the expansion of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet for several years, as the Fed emphasized intermediate- and long-term maturities as a mechanism by which to absorb the net issuance of US Treasury securities. Let’s think of it this way. The federal deficit was $1 trillion, and the Fed was buying securities at the rate of $85 billion per month, or approximately $1 trillion yearly. Thus, the Fed purchased the entire amount of issuance that the federal government presented to the market. If all things were otherwise neutral, the market impact was zero. There was no influence to change interest rates; hence they could stay very low. But in the economic recovery phase, the federal deficit commenced shrinking sooner than the Fed commenced tapering. There reached a point at which the Fed was acquiring more than 100% of the net new issuance of US government securities. At that point, the Fed’s buying activity was withdrawing those securities from holders in the US and around the world. Essentially the Fed was bidding up the price and dropping the yield of those Treasury securities, and it was doing so in the long-duration end of the distribution of those securities. The Fed has taken the duration of its assets from two years prior to the Lehman-AIG crisis all the way out to six years, which is the present estimate. It is hard to visualize the Fed taking that duration out any farther. There are not enough securities left, even if the Fed continues to roll every security reaching maturity into the longest possible available replacement security. We can conclude that the duration shift, otherwise known as a “twist,” is over. A six-year duration of the Fed’s balance sheet is about all one can reasonably expect them to obtain. Now the Fed commences the tapering process, incrementally stepping down its purchases of $85 billion per month to lesser amounts. The Fed has said that it will complete that task and reach zero before the end of this year. The target month is October. The current rate of purchases is $35 billion a month, or approximately $400 billion at an annualized run rate. The federal deficit has declined as well. Because of the shrinkage of the deficit, the run rate of Fed purchases and issuance by the US government are still about the same as the amount of Fed purchases. Before, the balance was $1 trillion issued and $1 trillion absorbed by the Fed. Presently, it is approximately $400 billion issued and $400 billion absorbed by the Fed. The Fed is on a glide path to zero, but the deficit remains a long way from zero. In July, August, September, and October of this year, for the first time, the net issuance of US government securities will exceed the absorption by the Fed as it tapers. The process of tapering is a gradual one that has been discussed by Fed officials continuously, and it is clear that, in the absence of some extreme reaction, they are going to sustain this path. What does that mean? By autumn, we will see issuance of US government securities at a rate of somewhere close to $400 billion annualized, whereas Fed absorption will be at zero. The Fed will continue to replace its maturities, but that practice will not add duration or supply any stimulus. In July, August, September, and October, for the first time, the change in rate between what the Fed absorbs and what the Treasury issues will result in a shift. That shift is a tightening. Will the markets respond to that tightening? We do not know. Have they responded to similar shifts in history? Absolutely. Could the shift be dramatic? We do not know. Could the response be benign? Yes. Could the response increase volatility and intensify market reactions to other events, many of which we have, for the purposes of this discussion, been assumed to be neutral? Absolutely. We are about to get back to a neutral place. The neutral place means the impact of issuance of debt by the government will again become a significant factor even if the rate is $400 billion per year. The other factors that we listed above and many more that have not been listed here are about to become more direct and substantial influences on interest rates. The reality is that their effects over the last seven years have been dampened by Fed policy. The effect of Fed policy on US-denominated assets has been to create a continued upward bias in the prices of those assets. Stocks, bonds, real estate, collectibles, and any asset that is sensitive to interest rates have had the benefit of this extraordinary policy for five or six years. That support is coming to an end. At Cumberland, we have no idea whether the transition will be benign and gradual or abrupt and volatile. There is no way to know. Therefore, we have taken a cash reserve position in our US ETF and US ETF Core accounts. We are maintaining that position as we navigate this transition period of July, August, September, and October. After years of stimulus, we’ve reached a tipping point that remaps the investing landscape in ways we cannot clearly foresee: for the rest of this year, tapering will be tightening. By Ambrose Evans-Pritchard 16 July, 2014 The US Federal Reserve has begun to pivot. Monetary tightening is coming sooner than the world expected, with sober implications for overheated bourses, and for those in Asia, eastern Europe and Latin America that drank deepest from the draught of dollar liquidity. We can expect a blistering dollar rally, perhaps akin to the early 1980s or the mid-1990s. It is fortuitous that the BRICS quintet of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa have just launched their $100bn monetary fund to defend each other's currencies. Some of them may need it. America's unemployment rate has fallen from 7.5pc to 6.1pc in 12 months. The country has been adding 230,000 jobs a month in the first half of this year. Since Fed chief Janet Yellen targets jobs above all else, this was bound to force capitulation by the Fed before long. It happened this week in her testimony to Congress. "If the labour market continues to improve more quickly than anticipated, then increases in the federal funds rate likely would occur sooner and be more rapid than currently envisioned," she said. This is a policy shift. Mrs Yellen has admitted that the Fed misjudged the pace of jobs recovery. The staff did not expect unemployment to fall this low until late next year. The inflexion point has come 15 months early. To some it feels like 2004, when the Greenspan Fed found itself badly behind the curve, suddenly switching from nonchalance in May to rate rises in June. "They may have left it too late again: the risk is a reckoning point when rates rise abruptly," said Jens Nordvig, from Nomura. Mrs Yellen added the usual caveats about "false dawns". Wages are barely rising. The jobs market is not yet drawing back the millions who dropped out of the system. The labour participation rate is still stuck at a 36-year low of 62.8pc, and at the lowest ever recorded for men. "The recovery is not yet complete. We need to be careful to make sure the economy is on a solid trajectory before we consider raising interest rates," she said. Yet she has undoubtedly changed gear. She no longer dismissed rising inflation (1.8pc) as "noise". She said share prices for biotech and social media companies were overheating, and that junk bonds were frothy. "Valuations appear stretched. We are closely monitoring developments in the leveraged loan market," she said. The critics may be getting to her. The Bank of International Settlements has rebuked the Fed for stoking asset bubbles. Some of her own voting committee are fretting. "I think we are going to overshoot on inflation,” said St Louis Fed chief James Bullard. Mrs Yellen is not as dovish as believed, in any case. Her lodestar is the "non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment" (NAIRU), the point at which tight labour markets start to drive a wage-price spiral. She thinks this is near 5.4pc. When the rate is above NAIRU, she is a dove: when below, she is a hawk. She was one of the first to call for pre-emptive rate rises in 1996 to choke inflation, dissenting from the Greenspan Fed. Nobody thought of her as dovish then. Her argument until now is that most of the jobless surge since the Great Recession is "cyclical and not structural" and therefore treatable by monetary stimulus. This is wearing thin. Skill shortages are cropping up everywhere. A Manpower survey of US firms found that 40pc are having trouble filling jobs. Total job openings have rocketed from 3.5m to 4.2m since January, the steepest rise in modern times. Quantitative easing has done its job, keeping growth alive as Congress and the White House pushed through the most draconian fiscal squeeze since the end of the Korean War. The economy did not fall back into recession, though it came close. It has achieved "escape velocity", of sorts. Yet if America is strong enough to withstand rate rises, it is far from clear what this will do to the rest of the world. A vast wash of dollars flooded the global financial system when the Fed cut rates near zero and then bought $3.5 trillion of bonds. This may now go into reverse. We still live in a dollarised world. Charles de Gaulle railed against the "exhorbitant privellege" of US dollar hegemony in the 1960s, but remarkably little has changed since. The BIS says global cross-border lending by banks alone has risen from $4 trillion to $10 trillion over the past decade, and $7 trillion of this is denominated in dollars. This does not include the dollar bond markets. What Fed now does arguably has more amplified effects than at any time since the end of gold and the collapse of the fixed-exchange Bretton Woods regime in 1971. This is the paradox of 21st century globalisation. Much of the dollar business is conducted through European and UK banks, leaving them acutely vulnerable to a dollar squeeze. Such episodes can be ferocious. It was a dollar liquidity shock that turned the Lehman affair into a global banking crisis, instantly engulfing Europe in October 2008. Emerging markets went into a tailspin last year at the first suggestion of Fed bond tapering. There was a sudden stop in capital flows. The "Fragile Five" (India, Indonesia, South Africa, Brazil and Turkey) were punished for current account deficits. The Fed backed down. The storm passed. There was a second "taper tantrum" earlier this year as the Fed finally began to pair back its $85bn monthly purchases under QE3. This too settled down. Those like India and Mexico that took advantage of the calm last Autumn to boost their defences were largely unscathed. Mrs Yellen has since recruited Bank of Israel veteran Stanley Fischer to be her number two, partly to navigate the reefs of emerging markets. However, that is not the end of story. A study by the International Monetary Fund concluded that the Fed's QE had pushed $470bn into emerging markets that would not otherwise have gone there. IMF officials say nobody knows how much of this hot money will come out again, or how fast. The BIS in turn said in its annual report two weeks ago that private companies had borrowed $2 trillion in foreign currencies since 2008 in emerging economies, lately at a real rate of just 1pc. Loans to Chinese companies have tripled to $900bn - some say $1.2 trillion - mostly through Hong Kong and often disguised by opaque swap contracts in what amounts a dangerous carry trade. Countries do not borrow in dollars any longer (mostly) but their banks and industries certainly do. The report said monetary largesse in the West has destabilised emerging economies in all kinds of ways. One of the worst - and least understood - ways is that they were forced to choose between internal credit bubbles or surging currencies. Most opted for bubbles as the lesser evil, holding their domestic interest rates at 300 basis points below the safe "Taylor Rule" level.

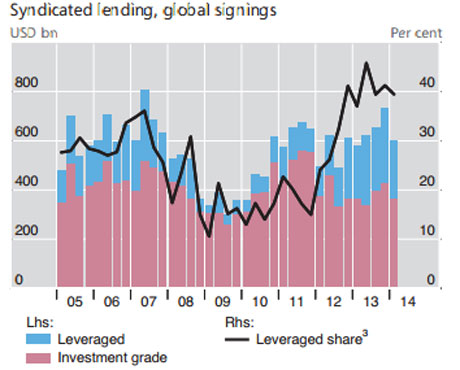

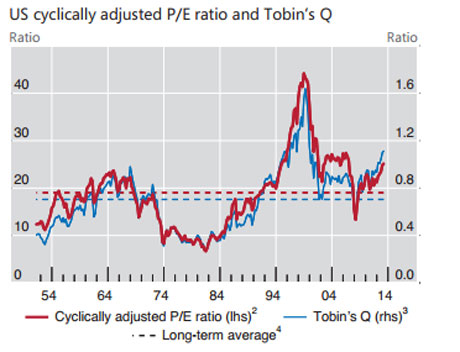

This has driven their total debt levels to a record 175pc of GDP. It may be even worse. China has thrown all caution to the wind, pushing credit from $9 trillion to $25 trillion since Lehman. Its debt levels have reached 220pc by some estimates. Officials at both the IMF and the BIS privately doubt whether China can extricate itself smoothly from this. Not all emerging markets are in the same boat. It is meaningless to compare Poland or the Czech Republic with Nicaragua. Yet there is no denying that a long string of countries are in structural crisis, ensnared by the middle-income trap. They have exhausted the low-hanging fruit of catch-up growth. They failed to carry market reforms to varying degrees. Productivity has wilted. Brazil, South Africa and Russia have all hit the buffers and all have a foot in recession right now, casualties of commodity addiction or the Dutch Disease. The outlook for Russia is utterly bleak. It has blundered into a conflict with the West that will smother investment for years, and it may have to draw down its reserves to cover $700bn of foreign currency debt unless it can tap the capital markets again. It faces demographic implosion. Now these countries - and many others with parallel problems, like autocratic Turkey under Tayyip Recep Erdogan - must brace for a secular rise in global borrowing costs, and as the BIS warns, the world is today more sensitive to interest rates than ever before. As yields on two-year US Treasuries ratchet higher, the US currency will inevitably ratchet with it. "I am convinced that we are close to a major cyclical recovery for the dollar," said Nomura's Mr Nordvig. The dollar did not rally in the tightening cycle of 2004 to 2007 but that was an exception, the result of the EMU bubble, as well as trillions of reserve accumulation by China and the commodity bloc, amid a feverish rotation into euro bonds. That chapter is closed. This time may look more like the traumatic episodes of the Volcker Fed, or the mid-1990s, both occasions when the world woke up to find the US had not spiralled into decline after all, and latterly was the only superpower left. The BRICS, the mini-BRICS and much of global finance have taken out a colossal short position on the US dollar. Mrs Yellen has just issued the first margin call. By Ambrose Evans-Pritchard 13 July, 2014 The world economy is just as vulnerable to a financial crisis as it was in 2007, with the added danger that debt ratios are now far higher and emerging markets have been drawn into the fire as well, the Bank for International Settlements has warned. Jaime Caruana, head of the Swiss-based financial watchdog, said investors were ignoring the risk of monetary tightening in their voracious hunt for yield. “Markets seem to be considering only a very narrow spectrum of potential outcomes. They have become convinced that monetary conditions will remain easy for a very long time, and may be taking more assurance than central banks wish to give,” he told The Telegraph. Mr Caruana said the international system is in many ways more fragile than it was in the build-up to the Lehman crisis. Debt ratios in the developed economies have risen by 20 percentage points to 275pc of GDP since then. Credit spreads have fallen to to wafer-thin levels. Companies are borrowing heavily to buy back their own shares. The BIS said 40pc of syndicated loans are to sub-investment grade borrowers, a higher ratio than in 2007, with ever fewer protection covenants for creditors. Their debt ratios have risen 20 percentage points as well, to 175pc. Average borrowing rates for five-years is 1pc in real terms. This is extemely low, and could reverse suddenly. “We are watching this closely. If we were concerned by excessive leverage in 2007, we cannot be more relaxed today,” he said. “It may be the case that the debt is better distributed because some highly-indebted countries have deleveraged, like the private sector in the US or Spain, and banks are better capitalized. But there is also now more sensitivity to interest rate movements." The BIS warned it is annual report two weeks ago that equity markets had become "euphoric". Volatility has dropped to an historic low. European equities have risen 15pc in a year despite near zero growth and a 3pc fall in expected earnings. The cyclically-adjusted price earnings ratio of the S&P 500 index in the US reached 25 in May, six points above its half-century average. The Tobin's Q measure is far more stretched than in 2007. “Overall, it is hard to avoid the sense of a puzzling disconnect between the markets’ buoyancy and underlying economic developments globally,” it said. Mr Caruana declined to be drawn on when the bubble will burst. "As Keynes said, markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent,” he said. The BIS says prolonged monetary stimulus in the US, Europe, and Japan has led to a leakage of liquidity, contaminating the rest of the world. The rising powers of Asia are no longer able to act as a firebreak – as they did after the Lehman crash –and may themselves now be a source of risk. Smackdown: smack·down, ˈsmakˌdoun/, noun, US informal The term “smackdown” was first used by professional wrestler Dwayne Johnson (AKA The Rock) in 1997. Ten years later its use had become so ubiquitous that Merriam-Webster felt compelled to add it to their lexicon. It may be Dwayne Johnson’s enduring contribution to Western civilization, notwithstanding and apart from his roles in The Fast and The Furious movie series. All that said, it is quite the useful word for talking about confrontations that are more for show than actual physical altercations. And so it is that on a beautiful July 4 weekend we will amuse ourselves by contemplating the serious smackdown that central bankers are visiting upon each other. If the ramifications of their antics were not so serious, they would actually be quite amusing. This week’s shorter than usual letter will explore the implications of the contretemps among the world’s central bankers and take a little dive into yesterday’s generally positive employment report. BIS: The Opening Riposte The opening riposte came from the Bank for International Settlements, the “bank for central banks.” In their annual report, released this week, they talked about “euphoric” financial markets that have become detached from reality. They clearly – clearly in central banker-speak, that is – fingered the culprit as the ultralow monetary policies being pursued around the world. These are creating capital markets that are “extraordinarily buoyant.” The report opens with this line: “A new policy compass is needed to help the global economy step out of the shadow of the Great Financial Crisis. This will involve adjustments to the current policy mix and to policy frameworks with the aim of restoring sustainable and balanced economic growth.” The Financial Times weighed in with this summary: “Leading central banks should not fall into the trap of raising rates ‘too slowly and too late,’ the BIS said, calling for policy makers to halt the steady rise in debt burdens around the world and embark on reforms to boost productivity. In its annual report, the BIS also warned of the risks brewing in emerging markets, setting out early warning indicators of possible banking crises in a number of jurisdictions, including most notably China.” “The risk of normalizing too late and too gradually should not be underestimated,” the BIS said in a follow-up statement on Sunday. “Particularly for countries in the late stages of financial booms, the trade-off is now between the risk of bringing forward the downward leg of the cycle and that of suffering a bigger bust later on,” the BIS report said. The Financial Times noted that the BIS “has been a longstanding sceptic about the benefits of ultra-stimulative monetary and fiscal policies, and its latest intervention reflects mounting concern that the rebound in capital markets and real estate is built on fragile foundations.” The New York Times delved further into the story: There is a disappointing element of déjà vu in all this,” Claudio Borio, head of the monetary and economic department at the BIS, said in an interview ahead of Sunday’s release of the report. He described the report “as a call to action.” Casual observers will be forgiven if they come away with the impression that the BIS document was seriously influenced by supply-siders and Austrian economists. Someone at the Bank for International Settlements seems to have channeled their inner Hayek. They pointed out that despite the easy monetary policies around the world, investment has remained weak and productivity growth has stagnated. There is even talk of secular (that is, chronic) stagnation. They talk about the need for further capitalization of many banks (which can be read, of European banks). They decry the rise of public and private debt. Read this from their webpage introduction to the report: To return to sustainable and balanced growth, policies need to go beyond their traditional focus on the business cycle and take a longer-term perspective – one in which the financial cycle takes centre stage. They need to address head-on the structural deficiencies and resource misallocations masked by strong financial booms and revealed only in the subsequent busts. The only source of lasting prosperity is a stronger supply side. It is essential to move away from debt as the main engine of growth. “Good policy is less a question of seeking to pump up growth at all costs than of removing the obstacles that hold it back,” the BIS argued in the report, saying the recent upturn in the global economy offers a precious opportunity for reform and that policy needs to become more symmetrical in responding to both booms and busts. Does “responding to both booms and busts” sound like any central bank in a country near you? No, I thought not. I will admit to being something of a hometown boy. I pull for the local teams and cheered on the US soccer team. But given the chance, based on this BIS document, I would replace my hometown team – the US Federal Reserve High Flyers – with the team from the Bank for International Settlements in Basel in a heartbeat. These guys (almost) restore my faith in the economics profession. It seems there is a bastion of understanding out there, beyond the halls of American academia. Just saying… Yellen’s Counter-Riposte On July 2, two days after the release of the BIS report, Janet Yellen took the stage at the IMF conference and basically said (translated into my local Texas patois), “Kiss my grits.” She was having nothing to do with risk and productivity and spent her time defending the low-rate environment she has been fostering in the US. With just a brief hat tip to the fact that monetary policy can contribute to risk-taking by going “too far, thereby contributing to fragility in the financial system,” she proceeded to maintain that monetary policy should “focus primarily on price stability in full employment because the cost to society in terms of deviations from price stability in full employment that would arise would likely be significant.” (You can read the speech here if you have nothing else to do and your recent entertainment options have been limited to watching the microwave cook.) In other words, Janet has her dual mandate, and the rest of the world can go pound sand. When she did allude to the risk of financial instability, she hastened to say that it was not something that would require a change in monetary policy but would instead call for what she termed a “more robust macroprudential approach.” In fact she used that word macroprudential no fewer than 29 times. For those not fluent in Fedspeak, what she meant is that we can deal with financial instability through increased regulation procedures, whatever the hell that means. Exactly what did macroprudential policy do for us during the last crisis? Hold that thought as we move on to Mario Draghi, who piled on the next day, as if to reemphasize that the leading central bankers of the world are simply not going to pay any attention to increasing financial instability risk. (Interestingly, the voice recognition software that I use to dictate this letter insists upon transcribing Draghi as druggie. Given what he is pushing, maybe it knows more than the typical software package.) Immediately following a European Central Bank meeting, Mario gave us the following statement: The key interest rates will remain at present levels for an extended period ... [and] the combination of monetary policy measures decided last month has led to a further easing of the monetary policy stance. The monetary operations to take place over the coming months will add to this accommodation and will support bank lending. My friend Dennis Gartman summarized the actual meaning of Draghi’s comments quite succinctly: In other words, European-style quantitative easing is now the course that the Bank shall take. As we understand it ... and this is a bit confusing and shall take a while to fully comprehend what the ECB has done and shall be doing ... the Bank will be making as much as €1 trillion available to the banks in two early tranches and will make that money available for the next four years as long as the money is being used for direct lending operations. My own interpretation is that Mario said, “I’ll see the Fed’s tapering and raise it by €1 trillion.” Wow! A double-teamed double smackdown! Even The Rock would be impressed. The Coming Liquidity Crisis The next crisis is shaping up to look a lot like the last one, just with a different cause. It is going to be a liquidity crisis. What was the cause of the last crisis? Everybody points to subprime debt, but that was really just a trigger. What happened was that everybody in the financial world became distrustful of everybody else’s balance sheet and so decided to go to cash, but there was so much debt and so much invested in illiquid assets that everybody couldn’t get out of the theater at the same time. It is happening again today. The intense drive for yield is driving down interest rates and volatility, pushing up assets of all kinds, and setting us up for the same song, second verse of the 2008 crisis. While I have been hinting around about that possibility for some time, it really crystallized for me this last week as I read about the enormous drop in quality of fixed-income paper of all types, coupled with the huge increase in junk paper. Then I read that that Kenya had just broken the African record for a sovereign debt sale. They raised $2 billion for “general budgetary purposes” and at a rate lower than they anticipated (6.875% for ten-year maturities). A commentator in the Financial Time noted wryly, “Kenya’s gotten really, really lucky with the yield…. There’s very strong global demand for African sovereign paper.” You bet there is, and on the corporate side of things, covenant-lite loans now amount to more than half of all corporate bonds outstanding, notes Barclays (and a dozen other sources). And meanwhile, the spread between AAA and subprime auto loans is the narrowest since 2007. “People just have to reach further and further,” says fund manager David Schawel to Bloomberg. “The objective now is to reach a certain yield target instead of feeling good about the underlying credit.” French ten-year bonds (OATS) are paying 1.7%. Spanish (2.68%) and Italian (2.83%) debt are paying roughly the equivalent of US debt. German debt, at 1.27%, pays less than half of US debt at 2.64%. Somewhere in that equation, sovereign debt is spectacularly mispriced. Rated ten-year corporate bonds are paying between 3% and 3.4%. That is less than a 1% premium for bonds that are only single-A. Seriously? The life insurance market is creating special-purpose vehicles (SPVs) for offloading their risk that are then guaranteed by the parent company. This is the subject of a very sobering report from the Minnesota branch of the Federal Reserve. Up to 25% of such debt may be subject to self-guarantees, and this debt is getting very high ratings. Whom are we kidding? (This is actually a very serious problem and needs an entire letter devoted to it. There’s just not enough time on a Friday afternoon, with the grill beckoning.) And we are going to have to deal with a run on everything, very similar to what happened last time, armed only with “macroprudential policy”? Precisely what additional rules are we going to enact? You are not allowed to sell what you own? Except if you say “Mother may I, with sugar on top?” A liquidity crisis cannot be dealt with by means of any regulatory policy I can think of, short of draconian limits on markets – really nasty limits, which sort of undermines the whole concept of a free market. But then, maybe I just have no imagination. If I could sit down with Chairwoman Yellen and ask her a few questions, chief among them would be: “What can macroprudential policies do in a liquidity crisis brought on by a reach for yield encouraged by your bank? Can you tell me exactly what those policies are?” There is a bull market in complacency. The illusion of central bank control is in full force. And one of the chief ironies is that a bull market can last longer than any of us can reasonably expect – and then end more abruptly than even the most cautious bulls suspect. The St. Louis Fed Financial Stress Index is at its lowest ebb since they began calculating the index. How much lower can it realistically go? The answer is that no one really knows. I don’t know what the trigger for the next debt crisis will be, but whatever it is, it will result in an even deeper liquidity crisis than we saw in ’08. That is just the nature of the beast.

You need to look into your portfolios, deep into your portfolios, and see what your various investments did back in 2008-09. Then take a deep, long, serious look in the mirror. Ask yourself, “Can I withstand another shock like that?” Do you think you are smart enough to pull the trigger to get out in time? Do you have automatic triggers that will cause you to exit without having to be emotionally involved? Are there illiquid assets in your portfolio that you want to own right on through the next crisis? (Let me note that there are a lot of assets about which you might answer positively, with a full-throated yes, in that regard.) Would you rather be biased to cash today, when cash is in a true bear market and at its lowest value in years, if that cash will give you the buying power to purchase assets at prices that will once again look like 2009’s? Think about how you will feel in the wake of the next crisis, when cash will be king! You should be thinking of cash not as cash per se, but as an option on future deep-value trades. There are few truisms in the investment world that are really valid, but one of them is that you make your money when you buy. That you sold at a profit is just another way of saying that you were smart to buy when you did. There is going to come a time when buying opportunities are once again going to be all around you. by Charles I. Plosser

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia President and Chief Executive Officer July 4th, 2014 As the Fed begins its 100th anniversary year, I believe it is entirely appropriate to reflect on its history and its future. At the same time, we need to reflect on what I believe is the Federal Reserve’s essential role and how it might be improved as an institution to better fulfill that role.1 Douglass C. North was cowinner of the 1993 Nobel Prize in Economics for his work on the role that institutions play in economic growth.2 North argued that institutions were deliberately devised to constrain interactions among parties both public and private. In the spirit of North’s work, one theme of this essay will focus on the fact that the institutional structure of the central bank matters. The central bank’s goals and objectives, its framework for implementing policy, and its governance structure all affect its performance. Central banks have been around for a long time, but they have clearly evolved as economies and governments have changed. Most countries today operate under a fiat money regime, in which a nation’s currency has value because the government says it does. Central banks are usually given the responsibility to protect and preserve the value or purchasing power of the currency.3 In the U.S., the Fed does so by buying or selling assets in order to manage the growth of money and credit. The ability to buy and sell assets gives the Fed considerable power to intervene in financial markets not only through the quantity of its transactions but also through the types of assets it can buy and sell. Thus, it is entirely appropriate that governments establish their central banks with limits that constrain the actions of the central bank to one degree or another. Yet, in recent years, we have seen many of the explicit and implicit limits stretched. The Fed and many other central banks have taken extraordinary steps to address a global financial crisis and the ensuing recession. These steps have challenged the accepted boundaries of central banking and have been both applauded and denounced. For example, the Fed has adopted unconventional largescale asset purchases to increase accommodation after it reduced its conventional policy tool — the federal funds rate — to near zero. These asset purchases have led to the creation of trillions of dollars of reserves in the banking system and have greatly expanded the Fed’s balance sheet. But the Fed has done more than just purchase lots of assets; it has altered the composition of its balance sheet through the types of assets it has purchased. I have spoken on a number of occasions about my concerns that these actions to purchase specific (non-Treasury) assets amounted to a form of credit allocation, which targets specific industries, sectors, or firms. These credit policies cross the boundary from monetary policy and venture into the realm of fiscal policy.4 I include in this category the purchases of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) as well as emergency lending under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, in support of the bailouts, most notably of Bear Stearns and AIG. Regardless of the rationale for these actions, one needs to consider the long-term repercussions that such actions may have on the central bank as an institution. As we contemplate what the Fed of the future should look like, I will discuss whether constraints on its goals might help limit the range of objectives it could use to justify its actions. I will also consider restrictions on the types of assets it can purchase to limit its interference with market allocations of scarce capital and generally to avoid engaging in actions that are best left to the fiscal authorities or the markets. I will also touch on governance and accountability of our institution and ways to implement policies that limit discretion and improve outcomes and accountability. Goals and Objectives The Federal Reserve’s goals and objectives have evolved over time. When the Fed was first established in 1913, the U.S. and the world were operating under a classical gold standard. Therefore, price stability was not among the stated goals in the original Federal Reserve Act. Indeed, the primary objective in the preamble was to provide an “elastic currency.” The gold standard had some desirable features. Domestic and international legal commitments regarding convertibility were important disciplining devices that were essential to the regime’s ability to deliver general price stability. The gold standard was a de facto rule that most people understood, and it allowed markets to function more efficiently because the price level was mostly stable. But the international gold standard began to unravel and was abandoned during World War I.5 After the war, efforts to reestablish parity proved disruptive and costly in both economic and political terms. Attempts to reestablish a gold standard ultimately fell apart in the 1930s. As a result, most of the world now operates under a fiat money regime, which has made price stability an important priority for those central banks charged with ensuring the purchasing power of the currency. Congress established the current set of monetary policy goals in 1978. The amended Federal Reserve Act specifies the Fed “shall maintain long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” Since moderate long-term interest rates generally result when prices are stable and the economy is operating at full employment, many have interpreted these goals as a dual mandate with price stability and maximum employment as the focus. Let me point out that the instructions from Congress call for the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to stress the “long run growth” of money and credit commensurate with the economy’s “long run potential.” There are many other things that Congress could have specified, but it chose not to do so. The act doesn’t talk about managing short-term credit allocation across sectors; it doesn’t mention inflating housing prices or other asset prices. It also doesn’t mention reducing short-term fluctuations in employment. Many discussions about the Fed’s mandate seem to forget the emphasis on the long run. The public, and perhaps even some within the Fed, have come to accept as an axiom that monetary policy can and should attempt to manage fluctuations in employment. Rather than simply set a monetary environment “commensurate” with the “long run potential to increase production,” these individuals seek policies that attempt to manage fluctuations in employment over the short run. The active pursuit of employment objectives has been and continues to be problematic for the Fed. Most economists are dubious of the ability of monetary policy to predictably and precisely control employment in the short run, and there is a strong consensus that, in the long run, monetary policy cannot determine employment. As the FOMC noted in its statement on longer-run goals adopted in 2012, “the maximum level of employment is largely determined by nonmonetary factors that affect the structure and dynamics of the labor market.” In my view, focusing on short-run control of employment weakens the credibility and effectiveness of the Fed in achieving its price stability objective. We learned this lesson most dramatically during the 1970s when, despite the extensive efforts to reduce unemployment, the Fed essentially failed, and the nation experienced a prolonged period of high unemployment and high inflation. The economy paid the price in the form of a deep recession, as the Fed sought to restore the credibility of its commitment to price stability. When establishing the longer-term goals and objectives for any organization, and particularly one that serves the public, it is important that the goals be achievable. Assigning unachievable goals to organizations is a recipe for failure. For the Fed, it could mean a loss of public confidence. I fear that the public has come to expect too much from its central bank and too much from monetary policy, in particular. We need to heed the words of another Nobel Prize winner, Milton Friedman. In his 1967 presidential address to the American Economic Association, he said, “… we are in danger of assigning to monetary policy a larger role than it can perform, in danger of asking it to accomplish tasks that it cannot achieve, and as a result, in danger of preventing it from making the contribution that it is capable of making.”6 In the 1970s, we saw the truth in Friedman’s earlier admonitions. I think that over the past 40 years, with the exception of the Paul Volcker era, we failed to heed this warning. We have assigned an ever-expanding role for monetary policy, and we expect our central bank to solve all manner of economic woes for which it is ill-suited to address. We need to better align the expectations of monetary policy with what it is actually capable of achieving. The so-called dual mandate has contributed to this expansionary view of the powers of monetary policy. Even though the 2012 statement of objectives acknowledged that it is inappropriate to set a fixed goal for employment and that maximum employment is influenced by many factors, the FOMC’s recent policy statements have increasingly given the impression that it wants to achieve an employment goal as quickly as possible.7 I believe that the aggressive pursuit of broad and expansive objectives is quite risky and could have very undesirable repercussions down the road, including undermining the public’s confidence in the institution, its legitimacy, and its independence. To put this in different terms, assigning multiple objectives for the central bank opens the door to highly discretionary policies, which can be justified by shifting the focus or rationale for action from goal to goal. I have concluded that it would be appropriate to redefine the Fed’s monetary policy goals to focus solely, or at least primarily, on price stability. I base this on two facts: Monetary policy has very limited ability to influence real variables, such as employment. And, in a regime with fiat currency, only the central bank can ensure price stability. Indeed, it is the one goal that the central bank can achieve over the longer run. Governance and Central Bank Independence Even with a narrow mandate to focus on price stability, the institution must be well designed if it is to be successful. To meet even this narrow mandate, the central bank must have a fair amount of independence from the political process so that it can set policy for the long run without the pressure to print money as a substitute for tough fiscal choices. Good governance requires a healthy degree of separation between those responsible for taxes and expenditures and those responsible for printing money. The original design of the Fed’s governance recognized the importance of this independence. Consider its decentralized, public-private structure, with Governors appointed by the U.S. President and confirmed by the Senate, and Fed presidents chosen by their boards of directors. This design helps ensure a diversity of views and a more decentralized governance structure that reduces the potential for abuses and capture by special interests or political agendas. It also reinforces the independence of monetary policymaking, which leads to better economic outcomes. Implementing Policy and Limiting Discretion Such independence in a democracy also necessitates that the central bank remain accountable. Its activities also need to be constrained in a manner that limits its discretionary authority. As I have already argued, a narrow mandate is an important limiting factor on an expansionist view of the role and scope for monetary policy. What other sorts of constraints are appropriate on the activities of central banks? I believe that monetary policy and fiscal policy should have clear boundaries.8 Independence is what Congress can and should grant the Fed, but, in exchange for such independence, the central bank should be constrained from conducting fiscal policy. As I have already mentioned, the Fed has ventured into the realm of fiscal policy by its purchase programs of assets that target specific industries and individual firms. One way to circumscribe the range of activities a central bank can undertake is to limit the assets it can buy and hold. In its System Open Market Account, the Fed is allowed to hold only U.S. government securities and securities that are direct obligations of or fully guaranteed by agencies of the United States. But these restrictions still allowed the Fed to purchase large amounts of agency mortgage-backed securities in its effort to boost the housing sector. My preference would be to limit Fed purchases to Treasury securities and return the Fed’s balance sheet to an all-Treasury portfolio. This would limit the ability of the Fed to engage in credit policies that target specific industries. As I’ve already noted, such programs to allocate credit rightfully belong in the realm of the fiscal authorities — not the central bank. A third way to constrain central bank actions is to direct the monetary authority to conduct policy in a systematic, rule-like manner.9 It is often difficult for policymakers to choose a systematic, rule-like approach that would tie their hands and thus limit their discretionary authority. Yet, research has discussed the benefits of rule-like behavior for some time. Rules are transparent and therefore allow for simpler and more effective communication of policy decisions. Moreover, a large body of research emphasizes the important role expectations play in determining economic outcomes. When policy is set systematically, the public and financial market participants can form better expectations about policy. Policy is no longer a source of instability or uncertainty. While choosing an appropriate rule is important, research shows that in a wide variety of models simple, robust monetary policy rules can produce outcomes close to those delivered by each model’s optimal policy rule. Systematic policy can also help preserve a central bank’s independence. When the public has a better understanding of policymakers’ intentions, it is able to hold the central bank more accountable for its actions. And the rule-like behavior helps to keep policy focused on the central bank’s objectives, limiting discretionary actions that may wander toward other agendas and goals. Congress is not the appropriate body to determine the form of such a rule. However, Congress could direct the monetary authority to communicate the broad guidelines the authority will use to conduct policy. One way this might work is to require the Fed to publicly describe how it will systematically conduct policy in normal times — this might be incorporated into the semiannual Monetary Policy Report submitted to Congress. This would hold the Fed accountable. If the FOMC chooses to deviate from the guidelines, it must then explain why and how it intends to return to its prescribed guidelines. My sense is that the recent difficulty the Fed has faced in trying to offer clear and transparent guidance on its current and future policy path stems from the fact that policymakers still desire to maintain discretion in setting monetary policy. Effective forward guidance, however, requires commitment to behave in a particular way in the future. But discretion is the antithesis of commitment and undermines the effectiveness of forward guidance. Given this tension, few should be surprised that the Fed has struggled with its communications. What is the answer? I see three: Simplify the goals. Constrain the tools. Make decisions more systematically. All three steps can lead to clearer communications and a better understanding on the part of the public. Creating a stronger policymaking framework will ultimately produce better economic outcomes. Financial Stability and Monetary Policy Before concluding, I would like to say a few words about the role that the central bank plays in promoting financial stability. Since the financial crisis, there has been an expansion of the Fed’s responsibilities for controlling macroprudential and systemic risk. Some have even called for an expansion of the monetary policy mandate to include an explicit goal for financial stability. I think this would be a mistake. The Fed plays an important role as the lender of last resort, offering liquidity to solvent firms in times of extreme financial stress to forestall contagion and mitigate systemic risk. This liquidity is intended to help ensure that solvent institutions facing temporary liquidity problems remain solvent and that there is sufficient liquidity in the banking system to meet the demand for currency. In this sense, liquidity lending is simply providing an “elastic currency.” Thus, the role of lender of last resort is not to prop up insolvent institutions. However, in some cases during the crisis, the Fed played a role in the resolution of particular insolvent firms that were deemed systemically important financial firms. Subsequently, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act has limited some of the lending actions the Fed can take with individual firms under Section 13(3). Nonetheless, by taking these actions, the Fed has created expectations — perhaps unrealistic ones — about what the Fed can and should do to combat financial instability. Just as it is true for monetary policy, it is important to be clear about the Fed’s responsibilities for promoting financial stability. It is unrealistic to expect the central bank to alleviate all systemic risk in financial markets. Expanding the Fed’s regulatory responsibilities too broadly increases the chances that there will be short-run conflicts between its monetary policy goals and its supervisory and regulatory goals. This should be avoided, as it could undermine the credibility of the Fed’s commitment to price stability. Similarly, the central bank should set boundaries and guidelines for its lending policy that it can credibly commit to follow. If the set of institutions having regular access to the Fed’s credit facilities is expanded too far, it will create moral hazard and distort the market mechanism for allocating credit. This can end up undermining the very financial stability that it is supposed to promote. Emergencies can and do arise. If the Fed is asked by the fiscal authorities to intervene by allocating credit to particular firms or sectors of the economy, then the Treasury should take these assets off of the Fed’s balance sheet in exchange for Treasury securities. In 2009, I advocated that we establish a new accord between the Treasury and the Federal Reserve that protects the Fed in just such a way.10 Such an arrangement would be similar to the Treasury-Fed Accord of 1951 that freed the Fed from keeping the interest rate on longterm Treasury debt below 2.5 percent. It would help ensure that when credit policies put taxpayer funds at risk, they are the responsibility of the fiscal authority — not the Fed. A new accord would also return control of the Fed’s balance sheet to the Fed so that it can conduct independent monetary policy. Many observers think financial instability is endemic to the financial industry, and therefore, it must be controlled through regulation and oversight. However, financial instability can also be a consequence of governments and their policies, even those intended to reduce instability. I can think of three ways in which central bank policies can increase the risks of financial instability. First, by rescuing firms or creating the expectation that creditors will be rescued, policymakers either implicitly or explicitly create moral hazard and excessive risking-taking by financial firms. For this moral hazard to exist, it doesn’t matter if the taxpayer or the private sector provides the funds. What matters is that creditors are protected, in part, if not entirely. Second, by running credit policies, such as buying huge volumes of mortgage-backed securities that distort market signals or the allocation of capital, policymakers can sow the seeds of financial instability because of the distortions that they create, which in time must be corrected. And third, by taking a highly discretionary approach to monetary policy, policymakers increase the risks of financial instability by making monetary policy uncertain. Such uncertainty can lead markets to make unwise investment decisions — witness the complaints of those who took positions expecting the Fed to follow through with the taper decision in September 2013. The Fed and other policymakers need to think more about the way their policies might contribute to financial instability. I believe that it is important that the Fed take steps to conduct its own policies and to help other regulators reduce the contributions of such policies to financial instability. The more limited role for the central bank I have described here can contribute to such efforts. Conclusion The financial crisis and its aftermath have been challenging times for global economies and their institutions. The extraordinary actions taken by the Fed to combat the crisis and the ensuing recession and to support recovery have expanded the roles assigned to monetary policy. The public has come to expect too much from its central bank. To remedy this situation, I believe it would be appropriate to set four limits on the central bank:

These steps would yield a more limited central bank. In doing so, they would help preserve the central bank’s independence, thereby improving the effectiveness of monetary policy, and, at the same time, they would make it easier for the public to hold the Fed accountable for its policy decisions. These changes to the institution would strengthen the Fed for its next 100 years. Weekly Market Comment by John P. Hussman, Ph.D. June 30, 2014 “I am definitely concerned. When was [the cyclically adjusted P/E ratio or CAPE] higher than it is now? I can tell you: 1929, 2000 and 2007. Very low interest rates help to explain the high CAPE. That doesn’t mean that the high CAPE isn’t a forecast of bad performance. When I look at interest rates in a forecasting regression with the CAPE, I don’t get much additional benefit from looking at interest rates… We don’t know what it’s going to do. There could be a massive crash, like we saw in 2000 and 2007, the last two times it looked like this. But I don’t know. I think, realistically, stocks should be in someone’s portfolio. Maybe lighten up… One thing though, I don’t know how many people look at plots of the market. If you just look at a plot of one of the major averages in the U.S., you’ll see what look like three peaks – 2000, 2007 and now – it just looks to me like a peak. I’m not saying it is. I would think that there are people thinking – way – it’s gone way up since 2009. It’s likely to turn down again, just like it did the last two times.” On a historical basis, the CAPE of over 26 is already quite enough to expect more than a decade of negative real total returns for the S&P 500. Aside from the crashes that followed the 1929, 2000 and 2007 peaks, a very long period of negative real returns also followed the other historical peak in the CAPE near 24 in the mid-1960’s. As noted above, one adjustment to the CAPE that significantly improves its relationship with actual subsequent market returns – as it does for numerous other measures – is to correct for the implied profit margin embedded into the multiple. This is true even though the denominator of the CAPE is based on 10-year averaging. At present, the margin embedded in the Shiller CAPE is more than 20% above the historical average. Adjusting for that embedded profit margin – which, again, produces a historically more reliable indication of actual subsequent S&P 500 total returns – the Shiller CAPE would presently be over 32. That level might make even Professor Shiller question whether stocks should be a material component of portfolios (at least for investors with horizons much shorter than the 50-year average duration of S&P 500 stocks). In any event, even the phrase “lighten up” is problematic for the market if more than a few investors heed that advice.

The ratio of non-financial equity market capitalization to GDP (which has maintained a tight correlation with subsequent 10-year S&P 500 total returns even in recent times) is now about 134%, compared with a pre-bubble norm of 55%. The median price/revenue ratio S&P 500 components easily exceeds, and the average rivals, the levels observed at the 2000 peak. All of this suggests that investors may not appreciate the extent of present overvaluation, lulled once again by the assumption that cyclically-elevated earnings are permanent. Benjamin Graham warned long ago that this assumption is probably the chief source of losses to investors: “The purchasers view the good current earnings as equivalent to ‘earning power’ and assume that prosperity is equivalent to safety.” Meanwhile, Fed Governor James Bullard observed last week that even the Fed is not inclined to maintain zero interest rate policy indefinitely: “Investors should be listening to the Committee. Of course, you can do what you want.” |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed