|

by Latha Venkate

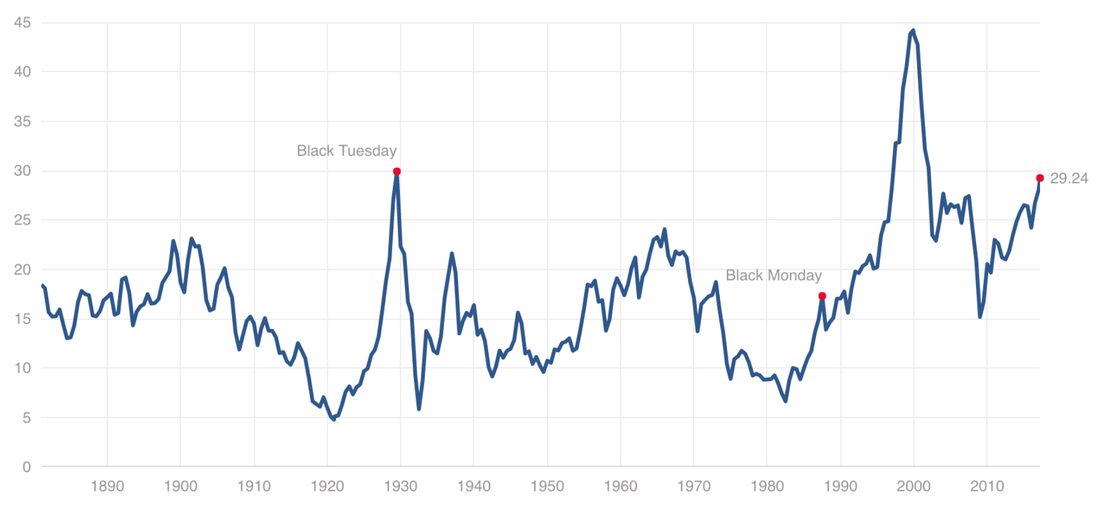

CNBC March 28,, 2017 In an interview to CNBC-TV18's Latha Venkatesh, Nassim Taleb, Statistician & Author of The Black Swan spoke about global economy and other related issues. Q: Let me start with an autobiographical question - you are one of those rare people who profited in the 1987 crash and in the 2007 crisis as well. Can you tell us something about what made you see this crisis coming and how did you profit from them? A: The first thing is that prediction is a wrong word because in a risk domain we do not talk of prediction. We talk about detection of fragility, so you have to detect what is fragile. If something is fragile eventually it is going to break. You can easily forecast that the coffee cup you have on a table is not going to outlive the table except maybe in rare circumstances. You can safely say that a pilot who is not very good at understanding storms eventually is going to have a funeral. So it's not forecasting; it is to understand what is fragile and what is not. So the first statement is to understand a fragile. The second thing, something that is fragile in a local way that's been your constraint, something systemic are fragile and these collapse. The crisis of 1987 had no idea about fragility. It's about 30 years ago and I was a trader, by then I was making bets on extreme events but some people substitute their own judgement that of others, but that I didn't take the answer and I said I am going to buy every single option I can. So before '87 there was Plaza Accord in '86 in which the market moved big time in currencies and we thought we are going to make little bit money - that was a business to me and so that is what happened to me. So there are two stories in there and actually reflected into my book - The Black Swan is about the incidence of these events and some domains. So basically what we have to do is to identify the domain in which it can happen. We know that 20 million people killed and penalty will happen to every 10 to 100, which we should basically never, whereas Ebola is more likely to do that. Therefore, identify the domain and second is identify the fragility. The two combined are crisis of 2008. For crisis of 2008, I was much more prepared. I was more comfortable and had written The Black Swan and I was completely depressed by the interpretation of my ideas about The Black Swan - it really got the point, as they said let's forecast -- that is not our work; detect fragility and the system was very fragile and it was described in The Black Swan as being fragile. So I came back. I thought I was done with trading, you cannot trade for too long, it becomes too stressful. You need time to recover of any activity and trading doesn't allow you that, you always have chronic stress. A chronic stress for 24 years was too much for me but then I started to come back, so I came back. So this is my autobiography. I then wanted to back out of the market. I wanted to be a scholar and initially I got into market not because of any economic reason or anything. I thought it was fun. It was really a fun to trade; trading is a lot of fun and it is like playing for living. So I did that and I got addicted to it. Q: Since you were once addicted to trading and even though now you are more a full time scholar than a trader, I do want to ask you where you see the top risk today or the top three risks today; after all we have seen a fairly decent Trump rally. There is a risk on across several financial assets. What would you say are the three big risks? A: The first big risk I see, let's forget about the economy and all that, it is really severe is from the reaction of Ebola. Why did I talk about Ebola because so I can follow-up now on a conversation by telling you what detected is a complete incompetence on a part of US authorities particularly state department in understanding the nature of multiplicative risk. A friend of mine, we analysed the situation and we called up the state department, a friend of mine contacted the state department and he told them every plane that leaves, every person with Ebola will have 500 exposures on a way and we was talking about the plague which was travelling with something like 30 miles a day. This is travelling much faster. These risks you have to recognise and they refused to recognise them and The New York Times published some comment saying it makes no sense to worry about Ebola. It only killed three Americans - this is what I picked up. So the way they reacted to the risks means lack of consciousness on a part of bureaucrats outside Singapore of course; Singapore understand it perfectly that emerging threats when they are systemic and multiplicative, need to be dealt with seriously. And I am afraid that because of antibiotic resistance should we have another plague that would travel very fast. Authorities in the past used to panic very quickly. Today they are talked by the risk management professor who never took risk, never worked for an insurance company, never did anything but these professors of finance for example say don't worry about it, it is statistically rare and stuff like that. So this is what worries me. Q: I must confess I wasn’t prepared for Ebola as an answer. What is the second big risk? A: Second one links to it, it can be used by terrorists. Q: Biological warfare you mean? A: Exactly. This is what we have to worry about, we don’t have to worry about conventional warfare. Of course it is a good idea for some people to convince you of it so they can sell you weapons but we have to worry about biological warfare first. That coupled with terrorism is a serious threat. So, that would be my second one. Now lets us talk finance. We had a crisis due to fragility of the financial system, too much debt, many people who shouldn’t lend were lending and many people who shouldn’t borrow were borrowing. Simple debt cycle that happened to correct like the forests. Forest has fires, clean ups the bad material. They kept perpetuating it with low interest rates under Greenspan. What did the US government do in conjunction with the Federal Reserve and don’t tell me it is independent of the Obama regime. So, what did they do? They kept interest rates very low and they let debt accumulate, transferred from individuals to the public sector, with hidden debt accumulating in form of all of the student loans but then much more seriously our liabilities with social security and all of that. So, now what do we have? We have a huge amount of debt, the government has USD 10 trillion more than it did before and interest rates are zero, so, the government deficit seems to be out of control. What if interest rates rose? Interest rates when they are at zero, first of all it is concave, in other words it is just like any ponzi scheme – you need to do more and more to keep it in place at the end. So, lower interest rates below 3 percent made no sense. Now we have something that is completely ineffective. You can no longer lower rates if you faced any further crisis and the resultant is printing money. So, now what’s the situation we are facing today? It is that we need to raise interest rates back up to normal levels say at least 3 percent. How do you do that? By raising rates. What happens when you raise rates? When you raise rates 0.25 points at a time, it’s not going to work. You are not going to get there. I remember in 1994 when Greenspan abruptly raised rates in United States financial markets did okay but worldwide – oh my god. We had for 2-3 years all this money flowing back to the states. So, we might be faced with a situation of say Tequila sort of crisis, facing the increase of interest rates in United States. Q: The previous hike of the US Federal Reserve did not evoke such strong reactions in financial markets. They were practically very well awaited, people were almost begging for a hike. Do you think things can still get out of hand? Of course Trump is speaking of more debt now – fiscal debt and how do you see therefore bond markets? A: First of all we haven’t seen the effect of last hike. After Greenspan some effects came upto a year later. However we have seen the effects of the monetary policy that we were doing before, inflating asset values. In fact during the Obama regime, it was the most interesting regime where we had stability at the expense of a median income that was increasing and a shift to inequality that was monstrously increasing simply because either people who had assets got richer and also because globalisation took place in that period of time and it had the effect whether we like it or not of causing winner take all effect. We spoke about the three risks, let me tell you what I think is not a risk. What is not a risk is this reaction – the Brexit reaction, the Trump reaction, it is a reaction by the grandmother, saying, there is something we don’t understand. When Nigel Farage speaks, they say I understand it, at least I know if he right or wrong. Whereas with the other guys we don’t know if they are right or wrong. When he went to Brussels, what we had in Europe was a symptomatic effect of last events as a concentration of a class of people who are bureaucrats, who have proved serial incompetence, they are not in business and also because they are not penalised for their mistakes. I don’t know many businesses in which a person making a mistake is not penalised. Whereas there it is completely insulated from that system. So, that class of people, you look at examples of how many documents they have regulating but they can’t control borders, they can’t control anything essential. So, what we have now is divorce between the notion of Europe and bureaucrats of Brussels. Q: Let us talk of the two risks separately. You spoke about Greenspan’s rate hike impact coming in much later. So, you still think that as the Federal Reserve hikes rates, we could still see some fairly drastic impact in financial markets a year down the line? A: The first thing you have to realise is already when you hike rates you are increasing the borrowing cost of the next government which are considerably higher today than they were in the past. 100 basis points is something like several hundred million dollars more. We are talking about increasing USD 53 billion defence spending, we don’t realise that 100 basis points or 200 basis points in expenditure is going to make that look like Friday afternoon pocket money for children. That is one thing you have to worry about. 25 basis points is symbolic and in effect other than US government and banks it doesn’t seem to impact people because nobody is borrowing. The point is only government is the one borrowing. If you look at the health of companies it is a completely different dynamics. Q: Do you think Europe is a big risk? We have got elections in France and Germany also coming up or do you think like Brexit, that is the known risk? A: To me Brexit was good news and effectively, from the beginning - I went on CNBC - before the Brexit, I went before the election of Trump to make sure to make my point is that should Trump be elected for number one, of course, I said it is not necessarily a bad thing that people tell you but that was not Trump that I was plugging. I was plugging the idea that if he is elected, the markets are not going to collapse. Q: I remember, November 3, you said Trump could get elected and he won't be apocalyptic. A: He will not be. Exactly, so stop worrying about this and something tells me that the healthiest Europe is a Europe that is managed by the smallest amount of people in Brussels. Q: You mean the breakup of Europe will not be apocalyptic? A: It is not a breakup. We live in a world of uberising relationships. So if you take the relationships of France with Morocco for example, you don't have to call Brussels to ask him for permission to do something. What is the aim of Europe? First of all, one thing about Europe that few understand that the notion of Europe isn't the classical Europe. That notion of Europe that they have is the Frankish Europe of Aix-la-Chapelle and Aachen and Germany of Charlemagne because the classical Europe is a Mediterranean. It is around the Mediterranean. Q: Closer to your home town? A: So, I am saying the Byzantine, that is a Roman empire, was the Byzantine Empire. So that is a classical Europe and then what you had out there is the rival to Byzantine. When Byzantine was there, these people who called themselves holy roman emperor and they had three things wrong. They were neither holy nor roman, Roman was Byzantium, Constantinople. He was the real emperor. So, the EU may end up and actually Martin Walls has made a similar remark, will end up as some paper organisation where people can go when they are fired from their job or when you want to get rid of them in Paris, you send them to Brussels or it is like sending someone to Coventry. It may survive that way because the holy Roman Empire survived a thousand years doing nothing. So you have to think about it, they had no power. So that is the notion. So you have to separate the idea of Europe and also understand that countries are adults. For example, take the UK. The UK wants, I put the question when I was I think, with David Cameron and he called it slander. I said, who do you identify with? And English speaking Indian person or someone from Poland? Who can you have dinner with? You sit down, you can communicate with someone brought up in Delhi, but you cannot communicate with someone brought up in Krakow. You get the idea? So why are we doing this? So you will say, it is of no European risk. So forget the notion of people being able to do deals together just like United States can do a deal now with Ireland hopefully and the UK where Americans can go work there, they can come work here, you can make agreements. So, you see the idea? So, countries are adults. But Norway and Switzerland, the two most successful countries in Europe are not in the EU. And people then worry about movement of population. Ireland and Cyprus are not in Schengen. So, it is like all these arguments seem to be like someone reacting without having a proper argument, sort of like if a lady goes in and tells her husband, listen I am divorcing you, goodbye. And then he has to come up with 10 arguments immediately, a not very well processed argument. These are the arguments used in favour of EU and against Brexit. I do not see any of them as economically reasonable nor even politically reasonable. The world does not like bureaucrats. Ancient Egypt and China collapsed after they bureaucratised the system. Q: Well that is one worry less. We should not worry about a confederating or perhaps, a splitting Europe. Let me come to India. We just had a gigantic experiment where our government changed 86 percent of the currency. A kind of demonetisation. Did you read about it? Any first comments? We seem to have come out of it with minor bruises. A: My first comment is that whenever economists tell you something is apocalyptic, it is not going to be. So, I do not know if it is good or bad but something was conveyed to me that a friend called me up and said, and actually I came to India right after that. And he said, every single economist said it made no sense, or at least economists that he knew said it made no sense. I said, every single economist said it made no sense, probably it is at least neutral. So, it does not have to be neutral. So, that is my idea. That is only thing I know about it. Now I do not understand the dynamics of what is going on, this I do not understand nor do I need to know. And I do not know much about India. I know stuff about India, but that is not the kind of stuff I understand. Q: I do not know how well you know our Prime Minister, Narendra Modi. He in a sense, single-handedly went into demonetisation. Do you think he is really making India anti-fragile? A: This I am going to tell you what I think I know about India from conversation and from visiting several clients. Every single Indian I meet tells me the same thing. They think that these sectors that do very well are sectors in which the government tried not to improve too much. I believe in government and I have heard Modi saying the government should not do to many things, but what the government does, should do it very well. So that is the idea. That is what I heard. But the problem is again to destroy the crust of people who make life difficult for others while genuinely thinking they are improving the system and reallocating. And the other thing is the first thing and it looks like it is part of the programme. Now in two years, I do not know how much was done in reducing the role of these things and hindering rather than advancing. And the second point that there was some element of decentralisation floating. And I think the decentralisation makes things look messy but better. by Akin Oyedele Business Insider March 14, 2017 Even Robert Shiller is worried about stock market valuations. The author of "Irrational Exuberance," a seminal book on volatility and behavioral economics that was released right as the dot-com bubble collapsed, is having flashbacks of that era. "The market is way overpriced," Shiller said, according to Bloomberg's Jason Clenfield and Adam Haigh. That is accurate by many measures, including Shiller's price-to-earnings ratio, which measures a stock's price relative to the last 10 years of the company's earnings. Its most recent reading on Monday was 29.24, a level not seen since the early 2000s when the internet bubble was leaking. Shiller likened the market's assessment of President Donald Trump's pro-business agenda to the awe that followed several internet companies as they grew in the late 1990s. Both periods can be described as "revolutionary," Shiller told Bloomberg, but investors are too focused on the positives and not so much the downside of Trump's agenda.

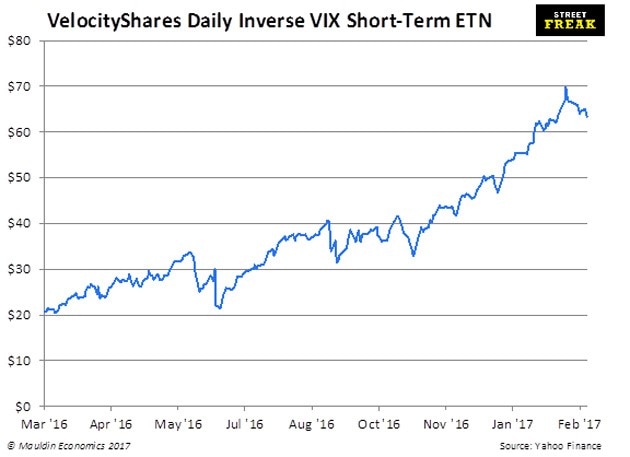

He did not forecast a short-term decline in stocks, but told Bloomberg that he wasn't buying more. The benchmark S&P 500 index has gained 11% since the election. While a five-quarter streak of year-on-year earnings declines ended in the fourth quarter, the market was also propelled by expectations for tax cuts and deregulation. As there hasn't yet been much implementation, several strategists have argued that stocks are due for a pullback that won't necessarily end the eight-year-old bull market. by Jared Dillian The 10h Man - Mauldin Economics March 2, 2017 You might remember The Incredible Drinking Bird joke from an old Simpsons episode. Homer wants to take a break from work, so he gets The Incredible Drinking Bird to hit the same key on the keyboard for him while goes out for a beer. The Incredible Drinking Bird is sort of a perpetual motion machine—it has a felt beak that dips in a glass of water, and then some chemical stuff happens in that bowl in the tail as the water evaporates and the bird tips over again. I had a colleague at Lehman Brothers who joked that the French banks got The Incredible Drinking Bird to hit the “sell vol” key on their keyboards. They just sold calls and puts on a daily basis, driving the vol into the mid-single digits. We joked that they probably booked the entire premium of the option as profit at the time of sale. Looks like someone has The Incredible Drinking Bird out there selling vol again. Check out this chart—there is always a bull market somewhere: That’s the chart of the inverse VIX ETN. Yes, there is such a thing, though it only has just over $500 million in assets.

Interesting tidbit about XIV: if the VIX were to go up a lot—say, 80% in a day—then XIV would be forced to redeem. It’s happened before, nearly 10 years ago to the day. Speaking of which, do you remember where you were on February 27, 2007? That was the opening salvo of the financial crisis, the day when the ABX gagged and China raised reserve requirements. We went from zero to OMG in the span of an afternoon. I tell people this all the time—in my entire career, I have never seen anything that crazy. It was also the highest vol-of-vol day in history. There is a lot of vol selling out there. People are willing to sell puts and calls for not very much, just to get a little yield out of their portfolio. And this, boys and girls, is one of the direct consequences of Zero Interest Rate Policy—people are incentivized to take stupid risks just to get a little yield. There were rumors going around last week about a fund getting itself into trouble by selling 1x5 upside call spreads, covering billions of delta as the market rallied. Nobody knows for sure if that’s what was driving the stock market higher, but it was a plausible theory, and it’s exactly the kind of behavior that gets people in trouble. Stress Test Here’s an exercise that we should all go through right now. You should stress test your portfolio. Picture some hypothetical awful situation—North Korea lobs a nuke into San Francisco, a true black swan—and try to predict how your portfolio would react in that disaster scenario. Do you feel like you have adequate protection? Oftentimes, buying protection for events like this is prohibitively expensive. Not now, though—now it is about as cheap as it gets. There is no reason not to own it. A lot of people will misinterpret me and say, “Dillian thinks something really bad is going to happen.” That is not the case at all. Really bad things are really unlikely. All I’m saying is, the cost of protecting yourself against really bad things can’t get much lower. But I will also say that it’s in times when people are most complacent that they should be the most vigilant. Usually it is the other way around—people are most vigilant when they should be complacent (like in the teeth of the financial crisis). I have been picking up anecdotes here and there. I’m sure many of you have come home from work to watch the Nightly News, only to have your spouse observe that the Dow is making record high closes on a daily basis, are we making money? Whenever you hear stories like that—run! There is an old saying on Wall Street: Buy it when you can, not when you have to. You can buy the one month puts in the S&P at a 7 vol. You have to when they’re at a 40 vol. Not to mention common sense. If you think we are getting through four years of a Trump/Bannon administration with the market this soporific, you are nuts. You Might Want to Rethink That Instead of selling options, how about buying options? I’m sure there are lots of covered call writers on this distribution. How about you stop writing covered calls? You are getting virtually nothing. Let me rephrase that: You are trading away all the upside and getting virtually nothing in return. Same goes for selling cash-secured puts. Better to do that when vol is high, not when vol is low. I’ve talked a lot about buying downside protection, but why not buy some upside as well? I really like “right-tail” strategies in the index, like buying the long-dated 3000 strike calls in the S&P 500. It’s only about a 30% move—not all that improbable. Plus, you get all the rho.1 I know people who absolutely cannot bring themselves to buy an option. As they say, 90% of them finish out of the money.2 If nothing else, buying options is a good regret-minimization strategy. Think of it as investing in mental capital. Take a few thousand bucks and just spend it on being able to sleep soundly at night. Sounds like a good investment to me. _____ 1 Exposure to higher interest rates. 2 I have no idea if this is true. by George Friedman

Geoplitical Futures March 6, 2017 Chinese Premier Li Keqiang told the National People’s Congress that China’s GDP growth rate would drop from 7 percent in 2016 to 6.5 percent this year. In 2016, the country’s growth rate was the lowest it had been since 1990. The precision with which any country’s economic growth is measured is dubious, since it is challenging to measure the economic activity of hundreds of millions of people and businesses. But the reliability of China’s economic numbers has always been taken with a larger grain of salt than in most countries. We suspect the truth is that China’s economy is growing less than 6.5 percent, if at all. The important part of Li’s announcement is that the Chinese government is signaling that it has not halted a decline in the Chinese economy, and that more economic pain is on the way. According to the BBC, Li said the Chinese economy’s ongoing transformation is promising, but it is also painful. He likened the Chinese economy to a butterfly struggling to emerge from its cocoon. Put another way, there are hard times in China that likely will become worse. China’s economic miracle, like that of Japan before it, is over. Its resurrection simply isn’t working, which shouldn’t surprise anyone. Sustained double-digit economic growth is possible when you begin with a wrecked economy. In Japan’s case, the country was recovering from World War II. China was recovering from Mao Zedong’s policies. Simply by getting back to work an economy will surge. If the damage from which the economy is recovering is great enough, that surge can last a generation. But extrapolating growth rates by a society that is merely fixing the obvious results of national catastrophes is irrational. The more mature an economy, the more the damage has been repaired and the harder it is to sustain extraordinary growth rates. The idea that China was going to economically dominate the world was as dubious as the idea in the 1980s that Japan would. Japan, however, could have dominated if its growth rate would have continued. But since that was impossible, the fantasy evaporates – and with it, the overheated expectations of the world. China’s dilemma, like Japan’s, is that it built much of its growth on exports. Both China and Japan were poor countries, and demand for goods was low. They jump-started their economies by taking advantage of low wages to sell products they could produce themselves to advanced economies. The result was that those engaged in exporting enjoyed increasing prosperity, but those who were farther from East China ports, where export industries clustered, did not. China and Japan had two problems. The first was that wages rose. Skilled workers needed to produce more sophisticated products were in short supply. Government policy focusing on exports redirected capital to businesses that were marginal at best, increasing inefficiency and costs. But most importantly – and frequently forgotten by observers of export miracles – is that miracles depend on customers who are willing and able to buy. In that sense, China’s export miracle depended on the appetite of its customers, not on Chinese policy. In 2008, China was hit by a double tsunami. First, the financial crisis plunged its customers into a recession followed by extended stagnation, and the appetite for Chinese goods contracted. Second, China’s competitive advantage was cost, and they now had lower-cost competitors. China’s deepest fear was unemployment, and the country’s interior remained impoverished. If exports plunged and unemployment rose, the Chinese would face both a social and political threat of massive inequality. It would face an army of the unemployed on the coast. This combination is precisely what gave rise to the Communist Party in the 1920s, which the party fully understands. So, a solution was proposed that entailed massive lending to keep non-competitive businesses operating and wages paid. That resulted in even greater inefficiency and made Chinese exports even less competitive. The Chinese surge had another result. China’s success with boosting low-cost goods in advanced economies resulted in an investment boom by Westerners in China. Investors prospered during the surge, but it was at the cost of damaging the economies of China’s customers in two ways. First, low-cost goods undermined businesses in the consuming country. Second, investment capital flowed out of the consuming countries and into China. That inevitably had political repercussions. The combination of post-2008 stagnation and China’s urgent attempts to maintain exports by keeping its currency low and utilize irrational banking created a political backlash when China could least endure it – which is now. China has a massive industrial system linked to the appetites of the United States and Europe. It is losing competitive advantage at the same time that political systems in some of these countries are generating new barriers to Chinese exports. There is talk of increasing China’s domestic demand, but China is a vast and poor country, and iPads are expensive. It will be a long time before the Chinese economy generates enough demand to consume what its industrial system can produce. In the meantime, the struggle against unemployment continues to generate irrational investment, and that continues to weigh down the economy. Economically, China needs a powerful recession to get rid of businesses being kept alive by loans. Politically, China can’t afford the cost of unemployment. The re-emergence of a dictatorship in China under President Xi Jinping should be understood in this context. China is trapped between an economic and political imperative. One solution is to switch to a policy that keeps the contradiction under control through the use of repression. The U.S. is China’s greatest threat. President Donald Trump is threatening the one thing that China cannot withstand: limits on China’s economic links to the United States. In addition, China must have access to the Pacific and Indian oceans for its exports. That means controlling the South and East China seas. As we have previously written, the U.S. is aggressively resisting that control. Faced with this same problem in the past, Japan turned into a low-growth, but stable, country. But Japan did not have a billion impoverished people to deal with, nor did it have a history of social unrest and revolution. China’s problem is no longer economic – its economic reality has been set. It now has a political problem: how to manage massive disappointment in an economy that is now simply ordinary. It also must determine how to manage international forces, particularly the United States, that are challenging China and its core interests. One move China is making is convincing the world that it remains what it was a decade ago. That strategy could work for a while, but many continue viewing China through a lens that broke long ago. But reality is reality. China no longer is the top owner of U.S. government debt, an honor that goes to Japan. China’s rainy day fund is being used up, and that reveals its deepest truth: When countries have money they must keep safe, they bank in the U.S. China carried out a great – and impressive – surge. But now it is just another country struggling to figure out what its economy needs and what its politics permit. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed