|

by George Soros

Project Syndicate June 25, 2016 Britain, I believe, had the best of all possible deals with the European Union, being a member of the common market without belonging to the euro and having secured a number of other opt-outs from EU rules. And yet that was not enough to stop the United Kingdom’s electorate from voting to leave. Why? The answer could be seen in opinion polls in the months leading up to the “Brexit” referendum. The European migration crisis and the Brexit debate fed on each other. The “Leave” campaign exploited the deteriorating refugee situation – symbolized by frightening images of thousands of asylum-seekers concentrating in Calais, desperate to enter Britain by any means necessary – to stoke fear of “uncontrolled” immigration from other EU member states. And the European authorities delayed important decisions on refugee policy in order to avoid a negative effect on the British referendum vote, thereby perpetuating scenes of chaos like the one in Calais. German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to open her country’s doors wide to refugees was an inspiring gesture, but it was not properly thought out, because it ignored the pull factor. A sudden influx of asylum-seekers disrupted people in their everyday lives across the EU. The lack of adequate controls, moreover, created panic, affecting everyone: the local population, the authorities in charge of public safety, and the refugees themselves. It has also paved the way for the rapid rise of xenophobic anti-European parties – such as the UK Independence Party, which spearheaded the Leave campaign – as national governments and European institutions seem incapable of handling the crisis. Now the catastrophic scenario that many feared has materialized, making the disintegration of the EU practically irreversible. Britain eventually may or may not be relatively better off than other countries by leaving the EU, but its economy and people stand to suffer significantly in the short to medium term. The pound plunged to its lowest level in more than three decades immediately after the vote, and financial markets worldwide are likely to remain in turmoil as the long, complicated process of political and economic divorce from the EU is negotiated. The consequences for the real economy will be comparable only to the financial crisis of 2007-2008. That process is sure to be fraught with further uncertainty and political risk, because what is at stake was never only some real or imaginary advantage for Britain, but the very survival of the European project. Brexit will open the floodgates for other anti-European forces within the Union. Indeed, no sooner was the referendum’s outcome announced than France’s National Front issued a call for “Frexit,” while Dutch populist Geert Wilders promoted “Nexit.” Moreover, the UK itself may not survive. Scotland, which voted overwhelmingly to remain in the EU, can be expected to make another attempt to gain its independence, and some officials in Northern Ireland, where voters also backed Remain, have already called for unification with the Republic of Ireland. The EU’s response to Brexit could well prove to be another pitfall. European leaders, eager to deter other member states from following suit, may be in no mood to offer the UK terms – particularly concerning access to Europe’s single market – that would soften the pain of leaving. With the EU accounting for half of British trade turnover, the impact on exporters could be devastating (despite a more competitive exchange rate). And, with financial institutions relocating their operations and staff to eurozone hubs in the coming years, the City of London (and London’s housing market) will not be spared the pain. But the implications for Europe could be far worse. Tensions among member states have reached a breaking point, not only over refugees, but also as a result of exceptional strains between creditor and debtor countries within the eurozone. At the same time, weakened leaders in France and Germany are now squarely focused on domestic problems. In Italy, a 10% fall in the stock market following the Brexit vote clearly signals the country’s vulnerability to a full-blown banking crisis – which could well bring the populist Five Star Movement, which has just won the mayoralty in Rome, to power as early as next year. None of this bodes well for a serious program of eurozone reform, which would have to include a genuine banking union, a limited fiscal union, and much stronger mechanisms of democratic accountability. And time is not on Europe’s side, as external pressures from the likes of Turkey and Russia – both of which are exploiting the discord to their advantage – compound Europe’s internal political strife. That is where we are today. All of Europe, including Britain, would suffer from the loss of the common market and the loss of common values that the EU was designed to protect. Yet the EU truly has broken down and ceased to satisfy its citizens’ needs and aspirations. It is heading for a disorderly disintegration that will leave Europe worse off than where it would have been had the EU not been brought into existence. But we must not give up. Admittedly, the EU is a flawed construction. After Brexit, all of us who believe in the values and principles that the EU was designed to uphold must band together to save it by thoroughly reconstructing it. I am convinced that as the consequences of Brexit unfold in the weeks and months ahead, more and more people will join us. by Mat Clinch

CNBC June 22, 2016 The organization commonly known as the central bank of central banks has called for an end of boom-and-bust cycles that have plagued the global economy, urging lawmakers quickly to adjust current policy. "The global economy cannot afford to rely any longer on the debt-fueled growth model that has brought it to the current juncture." the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) warns in a new annual report published on Sunday. Debt levels are too high, productivity growth is too low, and the room for policy maneuver is too narrow, the BIS warned. Adding that the most "conspicuous" sign of this predicament is interest rates that continue to be persistently and exceptionally low. Central banks around the world have leapt into action following the global financial crisis of 2008 and the sovereign debt crisis in the euro zone. Several institutions have introduced bond-buying programs and cut benchmark rates in an effort to stimulate lending. Some have even pushed rates below zero with a negative rate effectively charging banks who park cash at a central bank. The European Central Bank (ECB), the Danish National Bank (DNB), the Swedish Riksbank, and the Swiss National Bank (SNB) have all pushed key short-term policy rates into negative territory. This has suppressed bond yields in wider asset markets with BIS estimating that a record of close to $8 trillion in sovereign debt was trading at negative yields at the end of May. Nonetheless, the Basel-based BIS - which was one of the few organizations to foresee the 2008 crash - says that this monetary policy has been "overburdened for far too long." "Prudential, fiscal and, above all, structural policies must come to the fore," it said in the report Wednesday, adding that it's essential to avoid the temptation to succumb to "quick fixes or shortcuts." "The measures must retain a firm long-run orientation. We need policies that we will not once again regret when the future becomes today," it added. The BIS calls for the completion of banking rules on capital buffers to help in times of stress, and stresses that "stronger banks lend more." It also calls on governments to adjust their fiscal - or budgetary - rules to make them more countercyclical and reduce implicit guarantees, which may encourage risk-taking. Another policy that deserves consideration, according to BIS, is to use the tax code to restrict or eliminate the bias of debt over equity or reduce the effect of financial cycles The organization is renowned for its analysis of central banking and has regularly warned over the effects of stimuli such as quantitative easing. However, it was moderately upbeat on the global economy with regards to growth. "Judged by standard benchmarks, the global economy is not doing as badly as the rhetoric sometimes suggests," it said. "Global growth continues to disappoint expectations but is in line with pre-crisis historical averages, and unemployment continues to decline." by Joseph Ciolli

June 24, 2016 Selling in the U.S. stock market in the wake of the U.K.’s decision to secede from the European Union is just getting started for quantitative traders who make buy or sell decisions based on price trends, according to UBS Group AG. Their sales could total as much as $150 billion should equity volatility persist in the S&P 500 Index for the next week, derivatives strategist Rebecca Cheong said on Friday. The benchmark stock gauge fell 2.3 percent to 2,054.25 at 11:27 a.m. in New York, erasing a 2 percent rally over the prior four days. Strategies designed to mitigate risk will actually add to downward pressure in the S&P 500 over the next week as computerized selling ramps up to keep pace with falling prices. It reminds Cheong of the rapid stock selling that roiled markets in August, when the S&P 500 fell 11 percent to a 10-month low while facing similar behavior from algorithmic traders. “The bigger the down move today, the more they have to sell, which would basically create a vicious cycle,” Cheong, head of Americas equity derivatives strategy at UBS, said in a phone interview. “We’ll see front-loaded selling in the range of $100 billion to $150 billion over the next two to three days. It could be very similar to August in terms of model-based selling.” Rebalancing of risk control funds could result in up to $98 billion in S&P 500 selling should the index see price swings of about 3.5 percent or more over the next several days, according to Cheong. Risk parity instruments may stir up as much as $30 billion in selling given similar volatility, she said. Additional downward price momentum will be created as owners of leveraged exchange-traded funds linked to the CBOE Volatility Index buy more shares as part of their own rebalancing process, according to UBS. The volatility index, which generally trades inversely to the S&P 500, climbed 27 percent on Friday. “They’ll be buying volatility and selling the S&P,” said Cheong. “On days like today, when the VIX goes up, they have to buy.” by Leslie Shaffer

CNBC June 10, 2016 Central banks are essentially out of ammunition, with zero and negative interest rate policies spurring greater savings, not growth, said Michael Heise, chief economist at Allianz Group. Moves by central banks from Japan to the euro zone to slash interest rates below zero have upended financial markets: investors are now paying some governments for the privilege of parking their funds while commercial lenders are mulling storing their cash in costly vaults instead of keeping them with central banks. Despite the stimulus, economic growth remains feeble. "Monetary policy has basically run its course in stimulating the economies," said Heise in an exclusive interview with CNBC in Singapore. "The Japanese example is very telling." In late January, the Bank of Japan blindsided global financial markets by adopting negative interest rates for the first time ever - a move that should have spurred outflows of the local currency. But instead, the yen surged and signs of the intended effects, such as increased bank loans, have been scarce. "The impact of monetary policy is actually counter intuitive and that shows that there's a lot of uncertainty that policy makers are facing," Heise said. "They can't even be sure how their instruments are going to affect the economy." For one, the chief economist at Allianz, which had 1.723 trillion euros ($1.95 trillion) under management as of the end of 2015, noted that low-to-negative rates aren't encouraging spending, which is what textbook economics would suggest. "It is quite remarkable that savings rates are not going down, although savings in terms of return is completely unattractive," he said. Instead, he added, "there's a concern that the wealth not accumulating in a way that [people] can take care of their retirement income or other objectives you have when you save: for buying a house or protecting your children or sending your children to school." That's made the savings ratio "completely inelastic," while low capital costs have done the same to dampen investment, he said, noting that consumption has only been rising in Germany because of salary increases. A low cost of capital means that the "opportunity cost" -- or the cost of making one investment as opposed to another or not investing at all -- is also low, which may encourage companies to simply wait on the sidelines. Low interest rates have also not spurred bank loans, he noted. "Bank lending does not accelerate just because of low interest rates or a lot of liquidity. Liquidity was never the problem for bank lending," Heise said. "It's the capital situation of the banks and lack of demand for loans by the corporate sector and the households." But he pointed to signs this is changing in Europe as the economy there recovers. "Slowly, companies are becoming more courageous to take up some loans, but it does not have to do with the buying of government bonds by the European Central Bank," he said. But he noted that within Asia, he's hearing a shift toward structural reforms, rather than relying on monetary policy. "We've completely exploited that and it's high time to refocus on other policies," Heise said, noting that these efforts may vary across countries, such as reforming inefficient state-owned enterprises, focusing on infrastructure and education spending, attracting foreign investment or fighting corruption. But when it comes to the U.S. Federal Reserve, Heise still expects interest rate increases ahead. After last week's non-farm payrolls report came in well-below expectations, many analysts pushed back their expectations for an interest rate hike from previous forecast for June or July. But Heise said that while a June move was likely off the table, he still put a greater than 50 percent chance that the Fed will hike interest rates at its July meeting. He said there's still too many reasons for the Fed to move and that the labor market appeared to remain in fairly good shape, with some wage-growth acceleration, although there was room for the participation rate to rise. GS - One large drawdown can quickly erase returns that were accumulated over several years10/6/2016

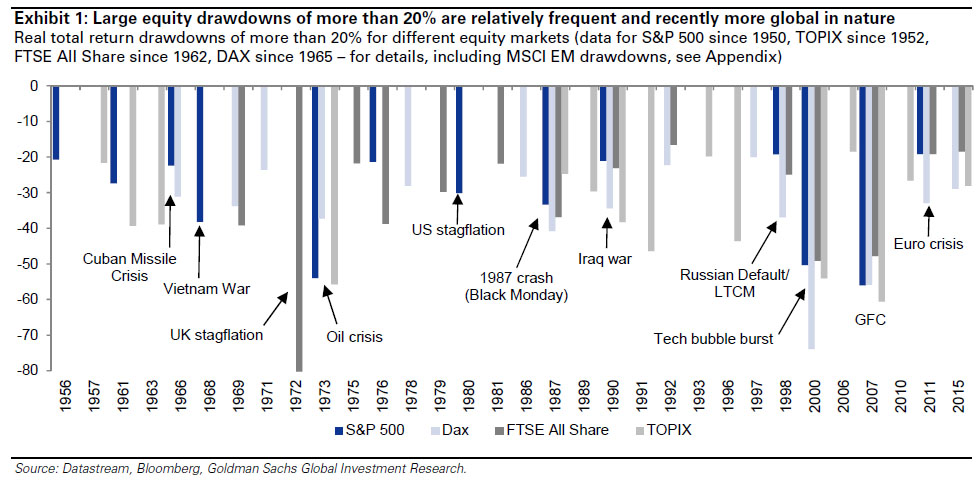

Goldman Sachs: "since the 1950s most equity markets had several large drawdowns of more than 20%, which have taken several years to recover from. For example in the 1970s the FTSE All-Share had an 80% drawdown in real terms and the DAX declined 69% during the Tech Bubble. One of the largest equity drawdowns across markets was during the GFC, when most global equity markets lost around half their value. And not to forget, the TOPIX has still not recovered from the large drawdowns of the late1980s/early 1990s."

by Gregory Zuckerman

Wall Street Journal June 8, 2016 After a long hiatus, George Soros has returned to trading, lured by opportunities to profit from what he sees as coming economic troubles. Worried about the outlook for the global economy and concerned that large market shifts may be at hand, the billionaire hedge-fund founder and philanthropist recently directed a series of big, bearish investments, according to people close to the matter. Soros Fund Management LLC, which manages $30 billion for Mr. Soros and his family, sold stocks and bought gold and shares of gold miners, anticipating weakness in various markets. Investors often view gold as a haven during times of turmoil. The moves are a significant shift for Mr. Soros, who earned fame with a bet against the British pound in 1992, a trade that led to $1 billon of profits. In recent years, the 85-year-old billionaire has focused on public policy and philanthropy. He is also a large contributor to the super PAC backing presumptive Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton and has donated to other groups supporting Democrats. Mr. Soros has always closely monitored his firm’s investments. In the past, some senior executives bristled at how he sometimes inserted himself into the firm’s operations, usually after the fund suffered losses, according to people familiar with the matter. But in recent years, he hasn’t done much investing of his own. That changed earlier this year when Mr. Soros began spending more time in the office directing trades. He has also been in more frequent contact with the executives, the people said. In some ways, Mr. Soros is stepping into a void at his firm. Last year, Scott Bessent, who served as Soros’s top investor and has a background in macro investing, or anticipating macroeconomic moves around the globe, left the firm to start his own hedge fund. Soros has invested $2 billion with Mr. Bessent’s firm, Key Square Group. Later in 2015, Mr. Soros tapped Ted Burdick as his chief investment officer. Mr. Burdick has a background in distressed debt, arbitrage and other types of trading, rather than macro investing, Mr. Soros’s lifelong specialty. That is why Mr. Soros felt comfortable stepping back in, the people said. Mr. Soros’s recent hands-on approach reflects a gloomier outlook than many others on Wall Street. His worldview darkened over the past six months as economic and political issues in China, Europe and elsewhere have become more intractable, in his view. While the U.S. stock market has inched back toward record levels after troubles early this year and Chinese markets have stabilized, Mr. Soros remains skeptical of the Chinese economy, which is slowing. The fallout from any unwinding of Chinese investments likely will have global implications, Mr. Soros said in an email. “China continues to suffer from capital flight and has been depleting its foreign currency reserves while other Asian countries have been accumulating foreign currency,” Mr. Soros said. “China is facing internal conflict within its political leadership, and over the coming year this will complicate its ability to deal with financial issues.” Mr. Soros worries that new troubles will arise in China partly because he said the nation doesn’t seem willing to embrace a transparent political system that he contends is necessary to enact lasting economic overhauls. Beijing has embarked on overhauls in the past year but has backtracked on some efforts amid turbulent markets. Some investors are beginning to anticipate rising inflation amid recent wage gains in the U.S., but Mr. Soros said he is more concerned that continued weakness in China will exert deflationary pressure—a damaging spiral of falling wages and prices—on the U.S. and global economies. Mr. Soros also argues that there remains a good chance the European Union will collapse under the weight of the migration crisis, continuing challenges in Greece and a potential exit by the United Kingdom from the EU. “If Britain leaves, it could unleash a general exodus, and the disintegration of the European Union will become practically unavoidable,” he said. Still, Mr. Soros said recent strength in the British pound is a sign that a vote to exit the EU is less likely. “I’m confident that as we get closer to the Brexit vote, the ‘remain’ camp is getting stronger,” Mr. Soros said. “Markets are not always right, but in this case I agree with them.” Other big investors also have become concerned about markets. Last month, billionaire trader Stanley Druckenmiller warned that “the bull market is exhausting itself” and hedge-fund manager Leon Cooperman said “the bubble is in fixed income,” though he was sanguine on stocks. Mr. Soros’s bearish investments have had mixed success. His firm bought over 19 million shares of Barrick Gold Corp. in the first quarter, according to securities filings, making it the firm’s largest stockholding at the end of the quarter. That position has gained more than $90 million since the end of the first quarter. Soros Fund Management also bought a million shares of miner Silver Wheaton Corp. in the first quarter, a position that has increased 28% so far in the second quarter. Meanwhile, gold has climbed 19% this year. But Mr. Soros also adopted bearish derivative positions that serve as wagers against U.S. stocks. It isn’t clear when those positions were placed and at what levels during the first quarter, but the S&P 500 index has climbed 3% since the beginning of the second period, suggesting Mr. Soros could be facing losses on some of those moves. Overall, the Soros fund is up a bit this year, in line with most macro hedge funds, according to people close to the matter. The investments by the firm were previously disclosed in filings, but it wasn’t clear how involved Mr. Soros was in the decisions spurring the moves. The last time Mr. Soros became closely involved in his firm’s trading: 2007, when he became worried about housing and placed bearish wagers over two years that netted more than $1 billion of gains. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed