|

Weekly Market Comments

by John P. Hussman, Ph.D. August 18, 2014 Excerpts: The stock market is presently a roulette wheel with dimes on black and dynamite on red. We continue to have extreme concerns about the extent of potential market losses over the completion of the present market cycle. At the same time, we have very little view with regard to short-term market action. If one reviews market action surrounding major pre-crash peaks such as 1929, 1972, 1987, 2000 and 2007, you’ll observe a sort of “resilience” in the major indices on a day-to-day and week-to-week basis even after market internals had already corroded. In 1987, for example, the break following the August bull market peak was largely recovered over the course of several weeks before failing rapidly in October. In 2000, the market actually experienced a series of 10-12% corrections and recoveries before a final high in September that was followed by a loss of half the market’s value. In 2007, the initial break in mid-summer was fully recovered, with the market registering a fresh nominal high in early October that marked the end of the bull market and the start of a 55% market collapse. As economic historian J.K. Galbraith wrote about the advance leading up to the 1929 crash, the market’s gains “had an aspect of great reliability… Indeed the temporary breaks in the market which preceded the crash were a serious trial for those who had declined fantasy. Early in 1928, in June, in December, and in February and March of 1929 it seemed that the end had come. On various of these occasions the Times happily reported the return to reality. And then the market took flight again. Only a durable sense of doom could survive such discouragement. The time was coming when the optimists would reap a rich harvest of discredit. But it has long since been forgotten that for many months those who resisted reassurance were similarly, if less permanently, discredited.” None of this implies that the market will or must collapse in short order. Stocks remain strenuously overvalued, overbought, and overbullish, but those conditions have persisted uncorrected much longer in the present instance than they have historically. That doesn’t encourage us to abandon our concerns, but it does make us less aggressive about investment stances that rely on any immediate unwinding of what we continue to view, along with 1929 and 2000, as one of the three most reckless equity bubbles in the historical record. ----- As I emphasized last week, “While we’re already observing cracks in market internals in the form of breakdowns in small cap stocks, high yield bond prices, market breadth, and other areas, it’s not clear yet whether the risk preferences of investors have shifted durably. As we saw in multiple early selloffs and recoveries near the 2007, 2000, and 1929 bull market peaks (the only peaks that rival the present one), the ‘buy the dip’ mentality can introduce periodic recovery attempts even in markets that are quite precarious from a full cycle perspective. Still, it's helpful to be aware of how compressed risk premiums unwind. They rarely do so in one fell swoop, but they also rarely do so gradually and diagonally. Compressed risk premiums normalize in spikes.” Those spikes will make it quite difficult to exit in the nice, orderly manner that speculators seem to imagine will be possible. Nor are readily observable warnings (beyond those we already observe) likely to provide a clear exit signal. Galbraith reminds us that the 1929 market crash did not have observable catalysts. Rather, his description is very much in line with the view that the market crashed first, and the underlying economic strains emerged later: “the crash did not come – as some have suggested – because the market suddenly became aware that a serious depression was in the offing. A depression, serious or otherwise, could not be foreseen when the market fell. There is still the possibility that the downturn in the indexes frightened the speculators, led them to unload their stocks, and so punctured a bubble that had in any case to be punctured one day. This is more plausible. “Some people who were watching the indexes may have been persuaded by this intelligence to sell, and others may have been encouraged to follow. This is not very important, for it is in the nature of a speculative boom that almost anything can collapse it. Any serious shock to confidence can cause sales by those speculators who have always hoped to get out before the final collapse, but after all possible gains from rising prices have been reaped. Their pessimism will infect those simpler souls who had thought the market might go up forever but who now will change their minds and sell. Soon there will be margin calls, and still others will be forced to sell. So the bubble breaks.” by Jeremy Grantham, GMO

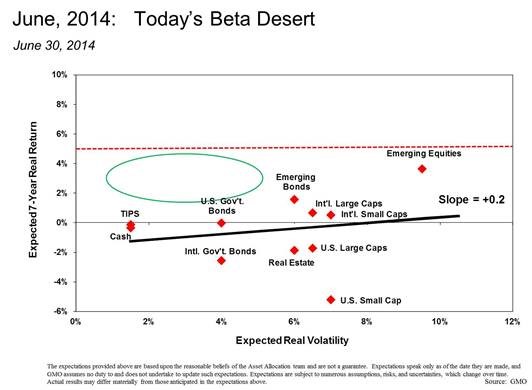

August 20, 2014 We have been writing quite a bit about why asset allocation today is in one of the toughest investing environments we’ve ever encountered. And it’s not just because we think equity markets are overvalued. No, we’ve seen that plenty of times before over the past decade or so. Remember the technology bubble of the late ’90s? That was challenging, sure, but what got lost in the shuffle was that while U.S. large-cap stocks were outrageously overpriced, it turned out that real estate investment trusts, emerging equities, and international small caps were deliciously priced. And it was perfectly clear to us what we had to do: avoid technology and own the cheap stuff, even though it might have looked a bit unconventional. Then we entered the 2007–2008 credit bubble, and while, yes, virtually all equity markets were overpriced, it was perfectly clear to us what we had to do: hide and wait. And that was not a bad proposition because there were plenty of safe places to hide—Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, U.S. Treasuries, and a strategy we had developed called Alpha Only—and earn a decent, if not spectacular, return. Today’s environment, however, is quite distinct, as seen in the chart below, where we lay out the GMO seven-year forecasts in a volatility (an imperfect shorthand for risk) versus return format for the traditional asset classes, or betas. This beta desert is so challenging because not only are there no asset classes that we believe are priced to deliver 5% real return (the red line), there is also no safe place to hide and wait (the green circle). * * * Then again, who needs "safety" when the market's Chief Risk Officer, the Federal Reserve of course, will never allow another market correction and when any wholesale selloff from this endless no volume elevitation will result in a CYNKing of the market, where the entire market is simply halted. Indefinitely. By Ritesh Anan in Hedge Funds, News, Options August 15, 2014 When George Soros takes a big position, everyone sits back and takes notice. The man who broke the Bank of England is known for not shying away from placing a big bet when he is convinced about something panning out exactly the way he foresees. One such trade that Soros has put up recently is a massive build up of a short position in SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust, placed under Put options. Though it can be that Soros is hedging his exposure to the stocks he is long in, but whether that is true or not are just guesses. “Soros Fund Management, the family office that manages the assets of billionaire George Soros, has just disclosed a huge bearish position on the S&P500, suggesting that Soros may think that the market is in for a big drop. According to the recent filings Soros’ fund company holds puts in the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY), which tracks the S&P500, totaling 11.29 million at the end of the second quarter, that was the time when many fund managers were fighting nerves about the state of the stock market [...],” Kelly said. Kelly revealed that Soros Fund Management also has old positions built over the past few years in the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY)’s Puts, but this recent position was by far the highest. Although it’s still not clear whether Soros still holds these Puts or not, but if he does, then the notional value of his SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY)’s Put position comes at around $2.2 billion. “[...] Still, it’s hard to read too much into the figure given that the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY) Put is a popular hedge and that Soros is long quite a few stocks as well. Positions that he may be trying to counterbalance, those of course include the Argentine oil company YPF, Teva Pharmaceutical, Tibco Software and a popular stock to talk about for us, which is Herbalife [...],” Kelly added. by Guy Haselmann Germany, France, Japan and the Eurozone are expected to follow Italy with flat or negative Q2 GDP when the data is released this week. Italy’s economy grew at -0.2% in Q2 and has not grown in over 10 years. Japan’s Q2 number tonight is expected to show an annualized decline worse than 7% (maybe <10%). These four countries collectively account for 18% of global GDP. In a globalized world with vast inter-connected supply chains, protectionism poses the most dangerous risk to economic growth. Sanctions against Russia combined with significant counter-measures have spanned and impacted international trade between dozens of countries. In India, newly-elected Modi’s government doubled the minimum price of exporting onions, and doubled tariffs on imported sugar to buoy the local industry. Sovereign actions to improve competitiveness are often taken to weaken a countries currency, but imposing tariffs and imposing protectionist laws have similar results but with far quicker and more targeted results. China’s powerful National Development and Reform Commission has gone after many multi-national foreign firms, hiding behind allegations of anti-monopoly practices (for WTO reasons). There have been several heavily-publicized raids where Chinese officials have interrogated corporate executives and confiscated computers. Some believe the motivation behind the raids is to incite nationalism to give a boost to less-competitive domestic products. Some of the firms involved include: Apple, Google, Walmart, Starbucks, McDonalds, Microsoft, Qualcomm, Symantec, and Chrysler. Executives fear the next step is seizure of property. The global monetary system is diverging and fraying. Central bank post-crisis quasi-coordination has broken down. Initially, foreign central banks unhappily followed the Fed in cutting rates toward zero; or else risked an appreciating currency affecting competitiveness. As domestic challenges developed and the Fed initiated ‘tapering’, many central banks pushed rates back up. Developed world economies have grown from around 30% of global GDP 20 years ago to 50% today. This improvement has helped motivate the unfolding of a new international economic order between developed and developing world economies. Geo-political tensions seem to inch ever-higher with each passing day. Protectionist actions are on the rise. Relationships amongst global trading partners are being altered. Supply chains are being disrupted. Shifting Fed policies are unsettling current imbalances (Note: The Jackson Hole forum begins Aug 21). Too many investors remain exposed to too many financial securities where, simply put, they are not being adequately compensated for the risk. Portfolios need to adjust to the changing landscape. Cash is king. Holding outsized allocations of cash has high optionality and low opportunity costs. The most liquid securities should command a liquidity premium. On-the-run Treasuries and high-quality corporates are preferred to most securities down the capital structure. The curve will continue to flatten over time. A liquidity-compromised over-shoot in risk assets is highly probable in the next few months. Investors should refrain, as much as possible, from being lulled into complacency by low market volatility or the Fed’s bold promises of providing a “highly accommodative stance” of monetary policy and a “gradual pace” of normalization. Markets are likely in for a wild ride for the balance of the year, due foremost by shifting central bank actions, rising geopolitical tensions, and increasing protectionist actions. For the most part, financial asset prices have performed well over the past 30 years. “Buy dip” typically worked. The main catalyst has been the Fed’s stair-stepping interest rates from the ‘high-teens’ to zero. However, since official rates have now (5 years ago) reached the end of the line (i.e. zero or ZIRP), and since the Fed balance sheet has reached its practical limit ($4.5 trillion or 40% of the market), shouldn’t risk assets have a negatively skewed risk/reward profile because the main upside catalyst has been exhausted? After all, prices can no longer be powered much further by interest rates. At some point equity valuations get ahead of themselves and can only be justified by above average economic growth (but the US is more likely to be trapped in the ‘new normal’). Paying higher asset price levels today lowers expected and actual returns tomorrow (that’s the simple math). Earning ever-lower returns creates a feedback loop of ever-extending risk profiles in search of better expected returns. The lower yields fall and the higher prices rise, the greater the risk. Fed-created moral hazard has cause irrationally low “risk premiums” at the precise time that there is enormous political and economic uncertainties, and little visibility.

David R. Kotok, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer

August 6-7, 2014 The ratio between the SKEW and VIX is a ratio of two different indices that measure option premiums. Those premiums give indications of market-based pricing of risk. When the SKEW-VIX ratio widens, it says that out-of-the-money options on American stocks are being bid up for the purposes of insuring against tail-risk events. Tail-risk events are higher-volatility swings, that is, swings that could be greater than one or maybe two standard deviations. History suggests that wide ratios between the SKEW and VIX result in market reactions that can be serious. That is why we watch the SKEW-VIX ratio. We give a hat tip to the analysts at BCA Research, who have discussed this in great detail in their work. We have taken the SKEW-VIX ratio, plotted it against the S&P 500 Index, and put it on our website for readers to see. The data starts in 2008. The ratio and the performance of the US stock market for the entire period of the financial crisis and subsequent rally can be seen. Look at it and draw your own conclusions. Here is the link: http://www.cumber.com/content/misc/SKEW-VIX.pdf. As this commentary is written, we still maintain a cash reserve and a defensive structure in portfolios. We think there is a still-evolving “fog of war.” We think that risks are rising for accidents, military interventions, and damage to economic recoveries. The world appears to be a very dangerous place. At the same time, we think that the central banks of the world are out of bullets when it comes to additional assistance in case there are shocks. The zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) around the globe has suppressed volatility for a long time. SKEW-VIX suggests that volatility may be returning. ----- When "buy the dips" becomes "sell the rallies,” it is time to re-examine your view of the world. Starting in the second half of this year, the stock markets in the US have changed. What was a long-term upward trend of five years has recently become a series of questions, in a climate characterized by rising uncertainty, added volatility, and greater risk. All these factors are discussed in detail in the new book. Starting in 2009, a large infusion of central bank-created liquidity fueled an improving outlook for economic recovery, which in turn spurred rising earnings expectations and higher stock prices. But now the long-market party from 2009 to 2014 has segued to a period of rising uncertainty. During the bull phase, the short-term and shallow corrections that led to subsequently higher stock prices on the rallies became the norm. The VIX measured this activity and declared it "complacency." The emerging dynamic, on the other hand, reflects concern about what happens when the Federal Reserve (Fed) comes away from the zero bound. What happens if the economic circumstances we have seen in recent years – the favorable breezes of gradually increasing growth, low inflation, no credit events, and no exogenous shocks or geopolitical risks of other types besides simple economics – shift to the gustier headwinds of a more troubled time? We measure this "tail risk” with the SKEW. Note that the SKEW–VIX ratio recently reached a record high. According to BCA Research (July 2014), SKEW pricing can reveal a rising probability of a "two standard deviation move." BCA suggests that the time horizon for such an event could well be within the next three months. We don't know for sure, of course; but the correction so far is over 5% and has broken through serious market levels. To complicate matters, geopolitical tensions have risen in many places worldwide and now pose significantly greater risk. Think about what happens if Vladimir Putin prohibits flights over some of the territory under his jurisdiction. Or consider the ramifications of a tank’s crossing the Russian border into Ukraine. Or think about what happens if a radical Islamic faction explodes a hydroelectric dam in Iraq. This is a dangerous world, and the markets sense that. At the same time, they are aware that the central banks' paths are not easily alterable. Think about the response function of the Fed to an extraneous shock. It cannot readily alter the tapering course it has set. It will be going to neutral. On the other hand, the European Central Bank has only one direction to go: stimulative. It faces a complex array of issues, and its foot-dragging may sink Europe into a full blown recession. Japan is likely to undertake another round of quantitative easing in the fall. The United Kingdom is in the throes of trying to extract itself from its former policy structure. In short, the world is no longer on a consistent, zero-interest-rate, QE path. Instead, the world is divided, and policy is ill-equipped to deal with mounting uncertainties. All of the above add to volatility in the market. For years now, in the US and elsewhere in the world, central banks have used zero interest rates to suppress volatility, creating a false sense of complacency. When markets anticipate the ending of a zero-interest-rate policy, volatility rises. We see this happening in the months of July and August. The concern is that we will see more volatility before this transitional period has run its course. As this commentary is written, we at Cumberland maintain a high cash reserve in our US exchange-traded fund managed accounts. We watch the SKEW and VIX daily. by David Stockman

August 1, 2014 During the last 64 months “buying the dips” has been a fabulously successful proposition. As shown in the sizzling graph of the NASDAQ 100 below, at it recent peak just under 4,000 this index of the high-growth, big cap non-financials stood at an astonishing 3.5X its March 2009 low. Moreover, during that 64 month period, there were but five minor market corrections—-the three largest reflecting just a 7-8% dip from the previous interim high. And as the index closed upon its current nosebleed heights, the dips became increasingly shallower, meaning that the reward for buying setbacks came early and often. So yesterday’s 2% dip will undoubtedly be construed as still another buying opportunity by the well-trained seals and computerized algos which populate the Wall Street casino. But that could be a fatal mistake for one overpowering reason: The radical monetary policy experiment behind this parabolic graph is in the final stages of its appointed path toward self-destruction. In fact, this soaring index reflects the most artificial, unsustainable and dangerous Fed created financial bubble ever. That’s because its was the untoward product of a completely busted monetary mechanism. What has happened is that the Fed’s historic credit expansion channel of monetary transmission has been frozen shut ever since day one of the massive Bernanke monetary expansion which began in August 2007, but went into warp-drive in the weeks after the Lehman event a year later. Yet this madcap money printing campaign was a drastic error because it failed to account for the immense roadblock to traditional monetary stimulus that had been built up over the last several decades—namely, “peak debt” in the household and business sector. This condition means that monetary easing and drastic interest rate cuts have not elicited a surge of consumer borrowing and business capital spending and hiring as during past business cycle recoveries. Instead, the entire tsunami of monetary expansion has flowed into the Wall Street gambling channel, inflating drastically every asset class that could be traded, leveraged or hypothecated. Stated differently, 68 months of zero interest rates had virtually no impact outside the the canyons of Wall Street. But inside the casino, they provided virtually free money for the carry trades, causing an endless bid for leveragable and optionable financial assets. But now that the monetary flood is cresting, financial asset values hang in mid-air like Wile E. Coyote. Stranded there, they are nakedly exposed to market discovery any moment now that the real economy and sustainable corporate earnings dwell in a region far below. That the credit channel of monetary expansion is busted and done is patently obvious in the data on the household sector. Below is both the current track of total household debt since the December 2007 peak, and the prior Greenspan housing bubble track. The latter turns out to be the last hurrah for the essential Keynesian “stimulus” gambit of the last several decades, which is to say, the one-time LBO of household balance sheets. During the 78 months since the last peak, household credit has shrunk by 5%. Nothing like this has every happened before. Not even remotely close. And in truth, the relevant shrinkage has been even greater, since more than 100% of the slight up-tick in borrowing shown in the graph for recent quarters is owing to the explosion of student debt. By contrast, the traditional source of household “borrow and spend”—-mortgage borrowings and credit card debt—-is still below its 7-year ago peak. Needless to say, this contrasts dramatically with the 78 month path after the 2001 cycle peak. During the Greenspan housing and credit bubble, household debt soared by nearly 90%, providing a robust, if temporary, boost to the consumption component of GDP. The reason for the sharp difference in the most recent cycle is that Keynesian stimulus was always an economic trick, not an permanently repeatable exercise in enlightened monetary management. Quite simply, the US household balance sheets—-as measured by outstanding credit market debt relative to wage and salary income—got used up during the decades after the nation’s fiat money debt binge incepted at the time of Camp David in August 1971. Now, in fact, the household leverage ratio has rolled over and is slowly retracing toward the still dramatically lower and more healthy levels that prevailed prior to 1971. In this context, it is surely the case that household leverage will continue to fall—-zero interest rates notwithstanding—– because it is a demographic given. The 10,000 baby boomers retiring each and every day between now and 2030 will not be adding to household debt; they will be liquidating it. What this means is that the motor force of traditional Keynesian expansion is gone. Household consumption spending, perforce, can now grow no faster than household income and economic production, and likely even more slowly than that. The coming funding crisis of the social insurance entitlements—Medicare and Social Security—will surely jolt the American public into a realization that higher private savings will be essential to retirement survival. Accordingly, the household savings rate has nowhere to go but up in the years just ahead. In any event, it is no mystery as to why business capital spending remains stuck on the flat-line. During the most recent quarter, real spending for plant and equipment was still 4% below its late 2007 peak——an outcome that is not even remotely comparable to the 10-25% surges that have occurred during comparable periods of prior business cycles. Business is not rushing to the barricades to add to capacity because it is plainly evident that consumer demand is not growing at traditional recovery cycle rates; and that it will never again do so given the constraints of peak debt and the baby boom retirement cycle ahead. As shown below, in fact, real net investment in CapEx—after allowance for depreciation of assets currently consumed—- is on a declining trend. Not only does this reflect the drastic downshift in the growth potential of the US economy that has set-in during the era of monetary central planning, but it also underscores that the current stock averages are capitalizing a future that is a pure chimera. At 19.5X reported LTM earnings, the S&P 500 is at the tippy top of its historical range, and at the point that it has invariably stumbled into a deep correction. Yet why is it rational to capitalize at even historic average PE multiples the earnings of an economy that is clearly locked into a low/no growth mode for as far as the eye can see? In truth, the market’s PE multiple should be well below the historic average generated during recent decades when Keynesian policy-makers were busy using up the nation’s balance sheets on a one-time basis in a nearly continuous campaign to stimulate credit-fueled growth. At the end of the day, even the heavily massaged data from the Washington statistical mills cannot hide this reality. Setting aside the short-run inventory swings which cloud the headline GDP numbers each quarter, and which accounted for nearly half of the 4% gain reported for Q2, real final sales tell the true story. Notwithstanding the Fed massive balance sheet expansion since its first big rate cut in August 2007—-that is, from $800 billion to $4.4 trillion—–real final sales have grown at less than a 1% CAGR since then. There is nothing like this tepid rate of trend growth for any comparable period in modern history. Indeed, given the clear bias toward under-reporting inflation in the BEAs GDP deflators, it is probable that during the last seven years the real economy has grown at a rate not far from zero. All of this means that the financial markets are drastically over-capitalizing earnings and over-valuing all asset classes. So as the Fed and its central bank confederates around the world increasingly run out of excuses for extending the radical monetary experiments of the present era, even the gamblers will come to recognize who is really the Wile E Coyote in the piece. Then they will panic. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed