|

The Telegraph

by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard 19 January, 2016 The global financial system has become dangerously unstable and faces an avalanche of bankruptcies that will test social and political stability, a leading monetary theorist has warned. "The situation is worse than it was in 2007. Our macroeconomic ammunition to fight downturns is essentially all used up," said William White, the Swiss-based chairman of the OECD's review committee and former chief economist of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). "Debts have continued to build up over the last eight years and they have reached such levels in every part of the world that they have become a potent cause for mischief," he said. "It will become obvious in the next recession that many of these debts will never be serviced or repaid, and this will be uncomfortable for a lot of people who think they own assets that are worth something," he told The Telegraph on the eve of the World Economic Forum in Davos. "The only question is whether we are able to look reality in the eye and face what is coming in an orderly fashion, or whether it will be disorderly. Debt jubilees have been going on for 5,000 years, as far back as the Sumerians." The next task awaiting the global authorities is how to manage debt write-offs - and therefore a massive reordering of winners and losers in society - without setting off a political storm. Mr White said Europe's creditors are likely to face some of the biggest haircuts. European banks have already admitted to $1 trillion of non-performing loans: they are heavily exposed to emerging markets and are almost certainly rolling over further bad debts that have never been disclosed. The European banking system may have to be recapitalized on a scale yet unimagined, and new "bail-in" rules mean that any deposit holder above the guarantee of €100,000 will have to help pay for it. The warnings have special resonance since Mr White was one of the very few voices in the central banking fraternity who stated loudly and clearly between 2005 and 2008 that Western finance was riding for a fall, and that the global economy was susceptible to a violent crisis. Mr White said stimulus from quantitative easing and zero rates by the big central banks after the Lehman crisis leaked out across east Asia and emerging markets, stoking credit bubbles and a surge in dollar borrowing that was hard to control in a world of free capital flows. The result is that these countries have now been drawn into the morass as well. Combined public and private debt has surged to all-time highs to 185pc of GDP in emerging markets and to 265pc of GDP in the OECD club, both up by 35 percentage points since the top of the last credit cycle in 2007. "Emerging markets were part of the solution after the Lehman crisis. Now they are part of the problem too," Mr White said. Mr White, who also chief author of G30's recent report on the post-crisis future of central banking, said it is impossible know what the trigger will be for the next crisis since the global system has lost its anchor and is inherently prone to breakdown. A Chinese devaluation clearly has the potential to metastasize. "Every major country is engaged in currency wars even though they insist that QE has nothing to do with competitive depreciation. They have all been playing the game except for China - so far - and it is a zero-sum game. China could really up the ante." Mr White said QE and easy money policies by the US Federal Reserve and its peers have had the effect of bringing spending forward from the future in what is known as "inter-temporal smoothing". It becomes a toxic addiction over time and ultimately loses traction. In the end, the future catches up with you. "By definition, this means you cannot spend the money tomorrow," he said. A reflex of "asymmetry" began when the Fed injected too much stimulus to prevent a purge after the 1987 crash. The authorities have since allowed each boom to run its course - thinking they could safely clean up later - while responding to each shock with alacrity. The BIS critique is that this has led to a perpetual easing bias, with interest rates falling ever further below their "Wicksellian natural rate" with each credit cycle. The error was compounded in the 1990s when China and eastern Europe suddenly joined the global economy, flooding the world with cheap exports in a "positive supply shock". Falling prices of manufactured goods masked the rampant asset inflation that was building up. "Policy makers were seduced into inaction by a set of comforting beliefs, all of which we now see were false. They believed that if inflation was under control, all was well," he said. In retrospect, central banks should have let the benign deflation of this (temporary) phase of globalisation run its course. By stoking debt bubbles, they have instead incubated what may prove to be a more malign variant, a classic 1930s-style "Fisherite" debt-deflation. Mr White said the Fed is now in a horrible quandary as it tries to extract itself from QE and right the ship again. "It is a debt trap. Things are so bad that there is no right answer. If they raise rates it'll be nasty. If they don't raise rates, it just makes matters worse," he said. There is no easy way out of this tangle. But Mr White said it would be a good start for governments to stop depending on central banks to do their dirty work. They should return to fiscal primacy - call it Keynesian, if you wish - and launch an investment blitz on infrastructure that pays for itself through higher growth. "It was always dangerous to rely on central banks to sort out a solvency problem when all they can do is tackle liquidity problems. It is a recipe for disorder, and now we are hitting the limit," he said. The Telegraph

by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard 20 January, 2016 The International Monetary Fund is increasingly alarmed by signs that market liquidity is drying up and may trigger an even more violent global sell-off if investors rush for the exits at the same time. Zhu Min, the IMF's deputy director, said the stock market rout of the last three weeks is just a foretaste of what may happen as the US Federal Reserve continues to raise interest rates this year, pushing up borrowing costs across the planet. He warned that investors and wealth funds have clustered together in crowded positions. Asset markets have become dangerously correlated, amplifying the effects of any shift in mood. "The key issue is that liquidity could drop dramatically, and that scares everyone," he told a panel at the World Economic Forum in Davos. "If everybody is moving together we don't have any liquidity at all. We have to be ready to act very fast," he said. Zhu Min said the worry is that policy-makers still do not understand the complex interactions in the global financial system, where vast sums of money can move across borders at lightning speed. What the IMF has observed is that market correlations are near an historic peak, with aligned positions in the US equity markets four times higher than the average since 1932. This is a recipe for trouble when the Fed is tightening. "When rates go up, market valuations have to adjust," he said. Harvard professor Kenneth Rogoff said the fear in the markets stems from a dawning realisation that the Chinese authorities are not magicians after all, and that this time the Fed may stand back and let the blood-letting run its course. "What is driving this is that the central banks are not coming to the rescue," he said, speaking at a Fox Business event hosted by Maria Bartiromo. Rates are already zero or below in Europe and Japan, and quantitative easing is largely exhausted, leaving it unclear what they could do next if the situation deteriorates. Prof Rogoff said these deep anxieties are causing companies to hold back investment, entrenching a slow-growth malaise. The Fed may be forced to halt its tightening cycle and even cut rates again if the wild sell-off continues for much longer. Prof Rogoff said the events of the last year had demolished the myth that China is a "perpetual growth machine" and could somehow escape the curse of the business cycle. It is the last domino of the "debt supercycle" to fall and the scale of it is the haunting spectre now hanging over the global economy. Nariman Behravesh, chief economist for IHS, said capital flight from China has reached $1 trillion since the mid-2015. "It has been massive. They have offset it by running down reserves but doing this is a form of monetary tightening. So what are they going to do now?" There is a risk that we could see a 20pc devaluation of the Chinese currency, and that really would push the world economy into recession Mr Behravesh said China is trapped by the "Impossible Trinity", unable to manage the exchange rate without losing control over internal monetary policy within a context of (partially) free capital flows. They are likely to opt for draconian capital controls as the lesser of evils, he said. But the danger for the world is that capital flight spins out of control and forces Beijing to abandon its defence of the yuan. "This all reminds me of the ERM crisis in Europe in the early 1990s. There is a risk that we could see a 20pc devaluation of the Chinese currency, and that really would push the world economy into recession," he said. Paul Singer, head of Elliott Management, said central banks have corrupted global assets markets with $15 trillion of bond and equity purchases over the last seven years, creating a total dependency on monetary largesse that must inevitably be all the more painful when it ends. The bond markets - supposedly safe - have become the epicentre of risk. "Things could be very disorderly. There is the potential for a tectonic shift if investors lose confidence in central banks," he said. by Christoph Gisiger

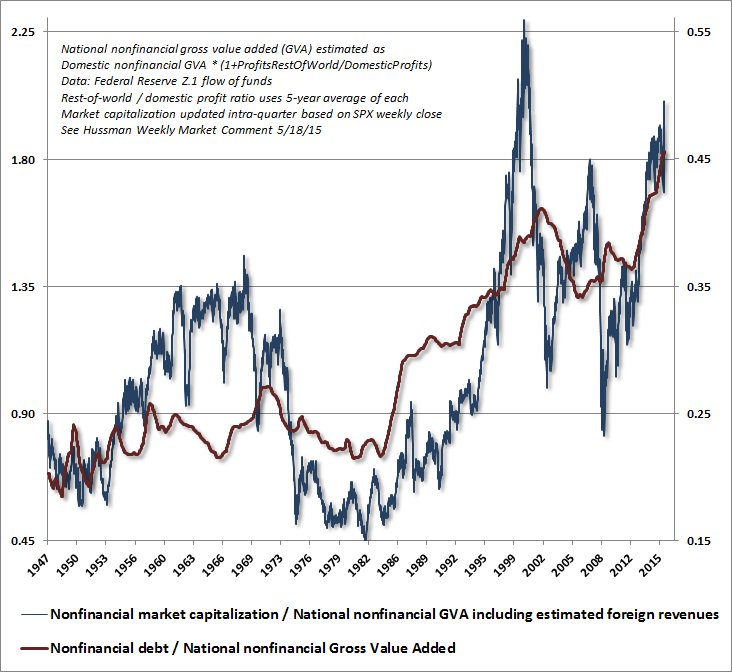

Finanz Und Wirtschaft Wall Street veteran Art Cashin warns that bankruptcies in the US oil industry could cause severe stress in the financial system. He believes the rate hike of the Federal Reserve was a mistake. Around the globe financial markets are in turmoil. Alarming news out of China and the crash in the oil market is causing angst among investors everywhere. In the United States, the S&P 500 (SP500 1890.9 0.56%) is down more than 8% since the beginning of the year. Art Cashin, director of floor operations for UBS (UBSG 17.06 1.85%) at the New York Stock Exchange, thinks that the rate hike of the Federal Reserve is one of the main reasons for the sell-off in the stock market. The highly respected Wall Street veteran fears that America will fall into a recession if the Fed doesn’t change its course and lowers interest rates back to zero. Mr. Cashin, the pressure on the financial markets is rising. How’s the mood on the trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange? The mood is both concerning and frustrated. On Friday, we traded temporarily lower than we got during the August spike down. That is never a good indication and it is troublesome. Here in the US, there was some concern that the markets will be closed for a holiday on Monday whereas the exchanges in Europe and in Asia are going to be open. So a lot of investors were worried about the exposure they will have for this extra day. You’re working on the floor of the stock exchange for almost six decades. During that time you have seen many difficult moments. How severe is the situation right now? It is very similar to what you get before you slip into a crisis. Also (ALSN 63.65 2.66%), it’s earnings season and because of that many corporate buybacks have to be paused during this period. That removes an important potential support for the market. Over the last year, companies buying back their own stock have put more money into the market than all of the public has. The stop of those buybacks is probably a reason why we’re seeing the rather sharp selling that has occurred. A main source of concern is the sharp drop in oil prices. Both, WTI and Brent, closed below $30 on Friday. Why is this causing so much havoc on Wall Street? Investors are concerned that many of the small and domestic producers here in the United States have money owned in the high yield market. So if oil prices continue to go lower they’re afraid that up to two thirds of those fracking companies may go into bankruptcy. They fear that through financial contagion those bankruptcies would then begin to spread into other areas of the financial markets. Are there already signs of contagion? Several market participants have been asked to put up more collateral to prepare for bad loans. Also, on Wednesday there were both rumors and indications that there was a good deal of forced selling going on. There were rumors that it could have been either a hedge fund or a sovereign wealth fund, maybe investors who are exposed to the oil prices. It could have been Saudi Arabia or Norway. Forced selling and margin calls are very hard to deal with because such an investor basically has no latitude. Positions must be sold at any price and that’s very difficult for the market. Also, there is alarming news coming out of China. What’s the problem here? On Friday, before trading started in New York, Chinese equity markets were down another 3,5% already overnight – and that is despite the best efforts of the Chinese government and the central bank to keep prices from destabilizing. Then again, the US economy seems hardly to be related to China. China is the second biggest economy in the world. The US may not sell much to China. But many of our economic partners like the countries in Europe do have big markets with China. There are other aspects to the China problem, too: The Chinese currency is relatively pegged to the US dollar. What’s the problem with that? When the Fed began raising interest rates and the dollar strengthened it made the Chinese currency go higher which put China at a disadvantage. So the Chinese began to try to find ways to slightly weaken their currency and that is disruptive throughout all the other currencies in the emerging markets and the small Asian economies. Back in 1997 when Thai baht broke everybody thought that won’t mean too much since the US doesn’t deal too much with Thailand. But in fact what happened was it rapidly spread through the financial industry and a great deal of money was lost. So investors are worried of seeing something like that happening again. So you think the rate hike of the Federal Reserve is one of the main sources for all the turmoil? The Chinese currency isn’t the only one that is under some stress. For instance, the Saudi Arabian currency is also partially pegged to the dollar. So you’re seeing many other nations beginning to suffer somewhat in reaction to the Fed move to begin raising rates. The appreciation of the dollar is also putting pressure on the export sector in the United States. Manufacturing has slowed down significantly over the last months. In its hundred year history the Fed had never before raised rates with the ISM index for the manufacturing sector below fifty which is showing that the manufacturing sector is in somewhat of a recession. I think the Fed basically painted itself into a corner. In September, because of the turmoil in the international markets, they were afraid to raise rates and they said: »We didn’t want to move with the markets destabilized.» Because of that they found some critics here in the US who said: »Hey, you’re the central bank of the United States and not the central bank of the world. Therefore, do worry about us and do what you think our economy requires. Don’t pay attention to other economies.» So when the December meeting came the Fed talked itself into a corner with no chance to change. On the other hand, many economists are seeing encouraging signs in the US labor market. In December payroll employment rose by over 290’000 and beat expectations handily. When you look closer into the numbers you see that 280’000 of those jobs were seasonal adjustments. In other words it wasn’t physical people standing there, it was an assumption by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. They said it was December and the weather normally is cold so they had to add on some people. And If you went over to the household survey you saw that 35% of the new jobs were people under the age of nineteen. In fact, only 3% of the jobs went to people in the prime category between the ages of 25 and 55. So the vast majority of the new jobs went to people under 24 and over 55. To me, that looked liked holiday hiring: people who make deliveries, wrap packages etc. These are not long lasting jobs. That’s why I think the next couple of payroll numbers will not show that kind of strength. So was it a policy mistake to raise rates? Yes, I thinks so. I believe we may be back at zero percent interest rates before we see one percent interest rates. I think the Fed will wind up having to do that to try to avoid a recession. Before they moved Christine Lagarde, the head of the IMF, told them they shouldn’t move. Larry Summers, the former secretary of the Treasury, told them they shouldn’t move. The Bank of International Settlements told them they shouldn’t move. But they insisted upon it and I think part of the turmoil that we are seeing now is indirectly connected with the Fed’s decision to go ahead. But on the day the Fed raised rates for the first time since the financial crisis many investors applauded and stock prices rallied. Why has the mood soured? The rate hike had to work its way through the system. Investors had to see what would happen to the Chinese currency and how the Chinese central bank and the Chinese government respond to what happened to their currency. Not a lot of people guessed that immediately when they saw that the Fed raised the rate. It’s now working through the system and it’s contributing to the turmoil that we’re experiencing. Looking ahead, what’s going to happen next? The bumpy ride is probably not over yet. I would remain very careful. I think efforts have to be made to stabilize the oil price. Investors have to review their risk exposure. So make sure you’re on guard. by John P. Hussman, Ph.D. January 4, 2016 Weekly Market Comment The chart below shows the ratio of nonfinancial market capitalization to corporate gross value added (GVA), along with the ratio of nonfinancial corporate debt to corporate GVA (right scale) which has surged to record-high levels. Understand that MarketCap/GVA is more tightly related to actual subsequent market returns on a 10-12 year horizon than any other measure, including the Fed Model, Price/forward earnings, the Shiller P/E, Tobin’s Q, or any other metric we’ve tested across history. To say that the financial markets are presently at a speculative extreme is an understatement. The ratio of nonfinancial market capitalization to corporate gross value added recently peaked at just above 2.0. Now, notice that even over the completion of the two most recent market cycles, when interest rates were quite depressed relative to historical norms, the ratio of MarketCap/GVA fell to just 1.0 or below. That’s certainly not a worst-case scenario (which would be closer to a ratio of 0.45-0.50 as we saw in 1950, 1974, and 1982). Indeed, we’ve never seen a bear market fail to take MarketCap/GVA to about 1.0 or below. For the S&P 500 to lose half of its value over the completion of the current market cycle would merely be a run-of-the-mill outcome given current extremes. A truly worst-case scenario, at least by post-war standards, would be for the S&P 500 to first lose half of its value, and then to lose another 55% from there, for a 78% cumulative loss, which is what would have to occur in order to reach the 0.45 multiple we observed in 1982. We do not expect that sort of outcome. But to rule out a completely pedestrian 40-55% market loss over the completion of the current cycle is to entirely dismiss market history.

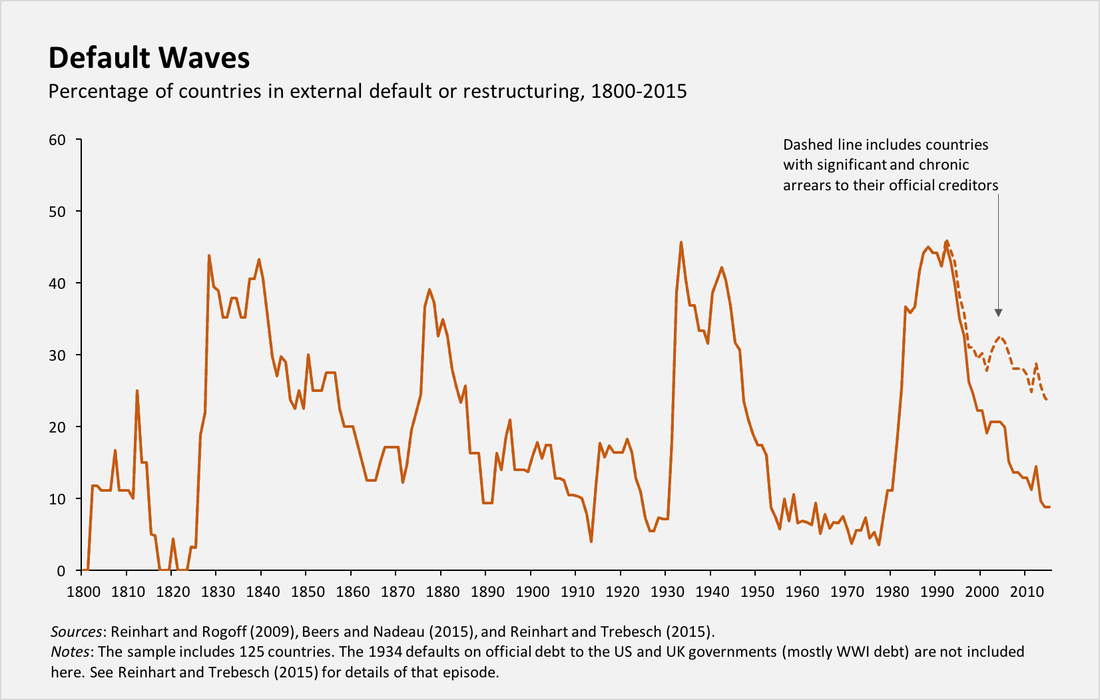

by Carmen Reinhart Project Syndicate December 31, 2015 MIAMI – When it comes to sovereign debt, the term “default” is often misunderstood. It almost never entails the complete and permanent repudiation of the entire stock of debt; indeed, even some Czarist-era Russian bonds were eventually (if only partly) repaid after the 1917 revolution. Rather, non-payment – a “default,” according to credit-rating agencies, when it involves private creditors – typically spurs a conversation about debt restructuring, which can involve maturity extensions, coupon-payment cuts, grace periods, or face-value reductions (so-called “haircuts”). Like so many other features of the global economy, debt accumulation and default tends to occur in cycles. Since 1800, the global economy has endured several such cycles, with the share of independent countries undergoing restructuring during any given year oscillating between zero and 50% (see figure). Whereas one- and two-decade lulls in defaults are not uncommon, each quiet spell has invariably been followed by a new wave of defaults. The most recent default cycle includes the emerging-market debt crises of the 1980s and 1990s. Most countries resolved their external-debt problems by the mid-1990s, but a substantial share of countries in the lowest-income group remain in chronic arrears with their official creditors. Like outright default or the restructuring of debts to official creditors, such arrears are often swept under the rug, possibly because they tend to involve low-income debtors and relatively small dollar amounts. But that does not negate their eventual capacity to help spur a new round of crises, when sovereigns who never quite got a handle on their debts are, say, met with unfavorable global conditions. And, indeed, global economic conditions – such as commodity-price fluctuations and changes in interest rates by major economic powers such as the United States or China – play a major role in precipitating sovereign-debt crises. As my recent work with Vincent Reinhart and Christoph Trebesch reveals, peaks and troughs in the international capital-flow cycle are especially dangerous, with defaults proliferating at the end of a capital-inflow bonanza. As 2016 begins, there are clear signs of serious debt/default squalls on the horizon. We can already see the first white-capped waves.

For some sovereigns, the main problem stems from internal debt dynamics. Ukraine’s situation is certainly precarious, though, given its unique drivers, it is probably best not to draw broader conclusions from its trajectory. Greece’s situation, by contrast, is all too familiar. The government continued to accumulate debt until the burden was no longer sustainable. When the evidence of these excesses became overwhelming, new credit stopped flowing, making it impossible to service existing debts. Last July, in highly charged negotiations with its official creditors – the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund – Greece defaulted on its obligations to the IMF. That makes Greece the first – and, so far, the only – advanced economy ever to do so. But, as is so often the case, what happened was not a complete default so much as a step toward a new deal. Greece’s European partners eventually agreed to provide additional financial support, in exchange for a pledge from Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras’s government to implement difficult structural reforms and deep budget cuts. Unfortunately, it seems that these measures did not so much resolve the Greek debt crisis as delay it. Another economy in serious danger is the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, which urgently needs a comprehensive restructuring of its $73 billion in sovereign debt. Recent agreements to restructure some debt are just the beginning; in fact, they are not even adequate to rule out an outright default. It should be noted, however, that while such a “credit event” would obviously be a big problem, creditors may be overstating its potential external impacts. They like to warn that although Puerto Rico is a commonwealth, not a state, its failure to service its debts would set a bad precedent for US states and municipalities. But that precedent was set a long time ago. In the 1840s, nine US states stopped servicing their debts. Some eventually settled at full value; others did so at a discount; and several more repudiated a portion of their debt altogether. In the 1870s, another round of defaults engulfed 11 states. West Virginia’s bout of default and restructuring lasted until 1919. Some of the biggest risks lie in the emerging economies, which are suffering primarily from a sea change in the global economic environment. During China’s infrastructure boom, it was importing huge volumes of commodities, pushing up their prices and, in turn, growth in the world’s commodity exporters, including large emerging economies like Brazil. Add to that increased lending from China and huge capital inflows propelled by low US interest rates, and the emerging economies were thriving. The global economic crisis of 2008-2009 disrupted, but did not derail, this rapid growth, and emerging economies enjoyed an unusually crisis-free decade until early 2013. But the US Federal Reserve’s move to increase interest rates, together with slowing growth (and, in turn, investment) in China and collapsing oil and commodity prices, has brought the capital inflow bonanza to a halt. Lately, many emerging-market currencies have slid sharply, increasing the cost of servicing external dollar debts. Export and public-sector revenues have declined, giving way to widening current-account and fiscal deficits. Growth and investment have slowed almost across the board. From a historical perspective, the emerging economies seem to be headed toward a major crisis. Of course, they may prove more resilient than their predecessors. But we shouldn’t count on it. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed