Evans-Pritchard - BIS discovers $14 trillion of dollar debt offshore, hidden in 'footnotes'25/9/2017

by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

17 September, 2017 The world’s top financial watchdog has uncovered $14 trillion of global dollar debt hidden in derivatives and swap contracts, a startling sum that doubles the underlying levels of offshore dollar credit in the international system. The scale of this lending greatly increases the risk of a future funding crisis if inflation ever forces the US Federal Reserve to tighten hard, draining worldwide liquidity and potentially triggering a dollar surge. A forensic study by the Bank for International Settlements says enormous liabilities have accrued through FX swaps, currency swaps, and ‘forwards’. The data is tucked away in the “footnotes” of bank reports. “Contracts worth tens of trillions of dollars stand open and trillions change hands daily. Yet one cannot find these amounts on balance sheets. This debt is, in effect, missing,” said the BIS analysis, written by team under chief economist Claudio Borio. “These transactions are functionally equivalent to borrowing and lending in the cash market. Yet the corresponding debt is not shown on the balance sheet and thus remains obscured,” they wrote in the BIS’s quarterly report. A breath-taking gap in global accounting rules mean that the debt is booked as a notional derivative, “even though it is in effect a secured loan with principal to be repaid in full at maturity.” The hidden lending comes on top of $10.7 trillion of recorded offshore dollar debt outside US jurisdiction. It pushes the combined total to $25 trillion or a third of global GDP. While these contracts serve as a lubricant and hedging device for world commerce, they can be plagued by currency and maturity mismatches. The dollar swaps serve as a ‘money market’ for global finance. Investors often take out short-term contracts that must be rolled over every three months. The great majority have maturities of less than a year. Much of the money is used to make long-term investments in illiquid assets, the time-honoured cause of financial of financial blow-ups. “Even sound institutional investors may face difficulties. If they have trouble rolling over their hedges, they could be forced into fire sales,” said the Swiss-based watchdog. While the BIS is careful to talk in broad terms, it is known that Chinese developers have borrowed heavily in US dollars through the FX swaps market. They do so because rates are lower and to dodge credit curbs. If funding suddenly dries up, Chinese regulators may be reluctant to bail them out for political reasons - until the situation is very serious. “A defining question for the global economy is how vulnerable balance sheets may be to higher interest rates,” said Mr Borio, the High Priest of the global banking fraternity. Signs of excess are visible everywhere. “Corporate debt is now considerably higher than it was pre-crisis. Leverage indicators have reached levels reminiscent of those that prevailed during previous corporate credit booms. A growing share of firms face interest expenses exceeding earnings before interest and taxes,” said the report. The BIS warned that margin debt used on equity markets exceeds the dotcom extreme in 2000. So-called ‘leveraged loans’ have surged to a record $1 trillion, and the share with risky ‘covenant-lite’ terms have jumped to 75pc. Everything looks fine so long as low bond yields underpin the asset edifice, but they may not stay low. “Equity markets continue to be vulnerable to the risk of a snapback in bond markets,“ it said. The structure is deeply unhealthy. Central bankers dare not lift rates despite economic recovery because of what they might detonate. “There is a certain circularity that points to the risk of a debt trap,” said Mr Borio. The Achilles Heel is global dollar debt. It was a seizure of the offshore dollar capital markets in late 2008 that turned the Lehman and AIG bankruptcies into a global event, and came close to bringing down the European banking system. “The meltdown in dollar-denominated structured products caused funding markets to seize up and banks to scramble for dollars. Markets calmed only after coordinated central bank swap lines to supply dollars,” said the BIS. The Fed effectively saved Europe from disaster. It is an open question whether the US Treasury would authorize such a rescue under the Trump Administration. The Sword of Damocles still hangs precariously a decade later. Global dependence on dollar liquidity has since become even more extreme. Over 90pc of all FX swaps and forwards worldwide today are in US currency. The dollar is even used within Europe for most swaps involving the Polish zloty or the Swedish krona for example, a pattern that would probably astonish European politicians. “The dollar reigns supreme,” said the BIS. What is odd is that Asian central banks and European multilateral bodies are huge players in this trade, effectively aiding and abetting a dangerous game. The message from a string of BIS reports is that the US dollar is both the barometer and agent of global risk appetite and credit leverage. Episodes of dollar weakness - such as this year - flush the world with liquidity and nourish asset booms. When the dollar strengthens, it becomes a headwind for stock markets and credit. If the dollar spikes violently, it sets off global tremors and a credit squeeze in emerging markets. This is what could happen again if President Trump’s tax reform plans lead to a big fiscal expansion and a repatriation of trillions of US corporate cash held overseas. Currency analysts say it would be an emerging market bloodbath. While the ‘fragile five’ - India, South Africa, Indonesia, Turkey, Brazil - have mostly cut their current account deficits and are in better shape than during the ‘taper tantrum’ of 2013, the problem has rotated to oil producers. China’s corporate debt has soared to vertiginous levels. Recorded dollar debt in emerging markets has doubled to $3.4 trillion in a decade, without including the hidden swaps. Local currency borrowing has risen by leaps and bounds. They are no longer low-debt economies. The BIS credit gap indicator of banking risk is flashing a red alert for Hong Kong, reaching 35pc of GDP. While it has dropped to 22.1pc in China, the country is still in the danger zone. Any sustained reading above 30 is a warning signal for a banking crisis three years later. Canada is also vulnerable at 11.3. Turkey (9.7) and Thailand (9) are on the edge. Most would be in trouble if global borrowing rose by 250 basis points. The UK is well-behaved on the credit gap metric. That is small comfort. There will be nowhere to hide if the world ever faces a dollar ‘margin call’. Shiller - The US stock market looks like it did before most of the previous 13 bear markets23/9/2017

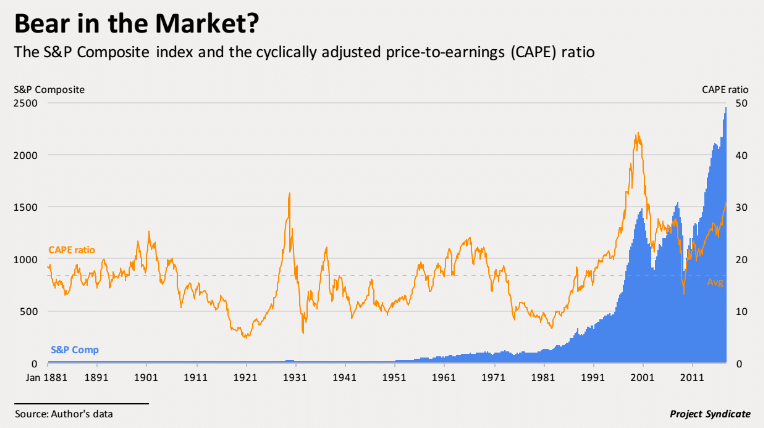

by Robert Shiller Project Syndicate September 22, 2017 The U.S. stock market today is characterized by a seemingly unusual combination of very high valuations, following a period of strong earnings growth, and very low volatility. What do these ostensibly conflicting messages imply about the likelihood that the United States is headed toward a bear market in stocks SPX, -0.04% ? To answer that question, we must look to past bear markets. And that requires us to define precisely what a bear market entails. The media nowadays delineate a “classic” or “traditional” bear market as a 20% decline in stock prices. That definition does not appear in any media outlet before the 1990s, and there has been no indication of who established it. It may be rooted in the experience of Oct. 19, 1987, when the stock market dropped by just over 20% in a single day. Attempts to tie the term to the “Black Monday” story may have resulted in the 20% definition, which journalists and editors probably simply copied from one another. Origin of the ‘20%’ figure In any case, that 20% figure is now widely accepted as an indicator of a bear market. Where there seems to be less overt consensus is on the time period for that decline. Indeed, those past newspaper reports often didn’t mention any time period at all in their definitions of a bear market. Journalists writing on the subject apparently did not think it necessary to be precise. In assessing America’s past experience with bear markets, I used that traditional 20% figure, and added my own timing rubric. The peak before a bear market, per my definition, was the most recent 12-month high, and there should be some month in the subsequent year that is 20% lower. Whenever there was a contiguous sequence of peak months, I took the last one. Referring to my compilation of monthly S&P Composite and related data, I found that there have been just 13 bear markets in the U.S. since 1871. The peak months before the bear markets occurred in 1892, 1895, 1902, 1906, 1916, 1929, 1934, 1937, 1946, 1961, 1987, 2000 and 2007. A couple of notorious stock-market collapses — in 1968-70 and in 1973-74 — are not on the list, because they were more protracted and gradual. CAPE ratio Once the past bear markets were identified, it was time to assess stock valuations prior to them, using an indicator that my Harvard colleague John Y. Campbell and I developed in 1988 to predict long-term stock-market returns. The cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio is found by dividing the real (inflation-adjusted) stock index by the average of 10 years of earnings, with higher-than-average ratios implying lower-than-average returns. Our research showed that the CAPE ratio is somewhat effective at predicting real returns over a 10-year period, though we did not report how well that ratio predicts bear markets This month, the CAPE ratio in the U.S. is just above 30. That is a high ratio. Indeed, between 1881 and today, the average CAPE ratio has stood at just 16.8. Moreover, it has exceeded 30 only twice during that period: in 1929 and in 1997-2002.

But that does not mean that high CAPE ratios aren’t associated with bear markets. On the contrary, in the peak months before past bear markets, the average CAPE ratio was higher than average, at 22.1, suggesting that the CAPE does tend to rise before a bear market. Moreover, the three times when there was a bear market with a below-average CAPE ratio were after 1916 (during World War I), 1934 (during the Great Depression) and 1946 (during the post-World War II recession). A high CAPE ratio thus implies potential vulnerability to a bear market, though it is by no means a perfect predictor. Earnings to the rescue? To be sure, there does seem to be some promising news. According to my data, real S&P Composite stock earnings have grown 1.8% per year, on average, since 1881. From the second quarter of 2016 to the second quarter of 2017, by contrast, real earnings growth was 13.2%, well above the historical annual rate. But this high growth does not reduce the likelihood of a bear market. In fact, peak months before past bear markets also tended to show high real earnings growth: 13.3% per year, on average, for all 13 episodes. Moreover, at the market peak just before the biggest ever stock-market drop, in 1929-32, 12-month real earnings growth stood at 18.3%. Another piece of ostensibly good news is that average stock-price volatility — measured by finding the standard deviation of monthly percentage changes in real stock prices for the preceding year — is an extremely low 1.2%. Between 1872 and 2017, volatility was nearly three times as high, at 3.5%. Low volatility Yet, again, this does not mean that a bear market isn’t approaching. In fact, stock-price volatility was lower than average in the year leading up to the peak month preceding the 13 previous U.S. bear markets, though today’s level is lower than the 3.1% average for those periods. At the peak month for the stock market before the 1929 crash, volatility was only 2.8%. In short, the U.S. stock market today looks a lot like it did at the peaks before most of the country’s 13 previous bear markets. This is not to say that a bear market is guaranteed: Such episodes are difficult to anticipate, and the next one may still be a long way off. And even if a bear market does arrive, for anyone who does not buy at the market’s peak and sell at the trough, losses tend to be less than 20%. But my analysis should serve as a warning against complacency. Investors who allow faulty impressions of history to lead them to assume too much stock-market risk today may be inviting considerable losses. Robert J. Shiller, a 2013 Nobel laureate in economics and professor of economics at Yale University, is co-author, with George Akerlof, of “Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception.” |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed