|

by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

The Telegraph July 27, 2016 The great fiscal fair of 2016 has begun. The world's governments are seizing on the flimsy excuse of Brexit to prime pump their economies, hoping to stretch the ageing global cycle for a little longer. Japan's Shinzo Abe has kicked off the first round with a "shock and awe" fiscal package ostensibly worth $270bn, though the South Koreans nipped ahead of him with a $17bn raft of measures. Britain cannot be far behind as Philip Hammond prepares his first post-austerity Budget this autumn, while France's Francois Hollande and Italy's Matteo Renzi have seized on Brexit to run a coach and horses through the eurozone's fiscal rules. Brexit is manna from heaven. Brussels hardly dares to raise a squeak, knowing that revolutionaries - the Front National and Beppe Grillo's Five Star movement - are knocking at the doors of power. Fiscal austerity is over in Europe. The details of the Japanese plan will be fleshed out next week. The infrastructure measures will include a push for the Maglev magnetic levitation train, which has already attained speeds of 600 km/h on a stretch rail beneath Mount Fuji. Mr Abe's plan amounts to 5.6pc of GDP, though the actual figure will be less once double counting is stripped out. This is far bigger than sums floated earlier by officials and would pack twice the punch of Japan's stimulus after the Lehman crisis. He has already postponed plans for a rise in the consumption tax until 2019. All pretence at fiscal rectitude has been abandoned. This "precautionary" stimulus has a loose parallel with the events of 1998 following the Asian financial crisis, when the US Federal Reserve and others slashed interest rates. The global authorities overdid it - easy to say in hindsight - setting off the final explosive phase of the dotcom bubble on Wall Street, with similar excesses on Germany's Neuer Markt. This time the policy mix is subtly different. Fiscal spending is the spearhead, backed by easy money. Japan is taking advantage of the new global orthodoxy. The International Monetary Fund - once the voice of fiscal restraint - wants "growth-friendly" spending to soak up chronic slack in the world economy, mostly on infrastructure schemes with the highest multiplier effect. "There is an urgent need for G-20 countries to step up their efforts to turn growth around," it said last week. Fixed public investment in the US has fallen to a 60-year low of 2.8pc of GDP, even though Kennedy Airport is crumbling and New York's gas mains date back 120 years or more. Almost fifty of the city's bridges are rated "fracture critical" and prone to collapse. Public investment has fallen to 2.6pc in the eurozone, and has been negative in Germany for much of the last fifteen years, though the Kiel Canal is falling into the water and the country's railways still rely on 19th Century signalling in places. In Japan it has fallen from 9.7pc to 3.9pc over the last two decades. None of this makes sense when there is so much excess capital in the world and $11 trillion of sovereign debt is trading at negative yields, allowing governments to borrow for twenty or thirty years for almost nothing. Debt ratios are higher, but debt service costs in the US have dropped to just 1.2pc of GDP from 3pc in the early 1990s. Mislav Matejka and Emmanuel Cau from JP Morgan has created a series of "fiscal baskets" for investors. "We believe that it is prudent to begin adding to stocks that could benefit from a potential increase in fiscal spend and from infrastructure projects," they said. They like Haynes, Atkins, Balfour Beatty, Costain, and Kier Group, among others, in the UK; Siemens, ThyssenKrupp, Thales, Alstom, and Dong Energy in Europe; General Electric, Steel Dynamics, and Texas Instruments in the US; and Tokyo Steel, and Osaka Gas in Japan. The beauty of fiscal stimulus is that it goes directly into the veins of the real economy. There is by now near universal agreement that reliance on zero rates and quantitative easing merely to drive up asset prices have reached their limits, rewarding the owners of capital with precious little trickle-down to the working poor. The politics are poisonous. Some of Mr Abe's spending will go on child-care and homes for the elderly. You could question whether a country with public debts near 250pc of GDP can afford to borrow yet more to fund social welfare, but debt is a mirage in a world of helicopter money. The Bank of Japan is monetising the entire budget deficit, buying $76bn of bonds each month. Former Fed chief Ben Bernanke floated the idea of a “money-financed fiscal programme” earlier this month in Tokyo but some would say that is exactly what they are already doing. The BoJ's balance sheet has reached 92pc of GDP. It owns 38pc of the Japanese government bond market, rising to 60pc by 2019. Whether such central bank adventurism is a free lunch remains to be seen. There is no sign yet of an inflationary 'pay-back', the moment when the chickens come home to roost. Japan can borrow for fifteen years at minus 0.05pc. My own view - not yet with full conviction - is that global growth will accelerate in the second half. The Fed's retreat from four rate rises this year has been a powerful tonic for emerging markets, while there is still enough fiscal stimulus in the pipeline to keep China's mini-boom going for a few more months. You can see the largesse in the global money supply figures. Simon Ward from Henderson Global Investors says his key measure - six-month real M1 money - is rising at a rate of 10.5pc, the fastest since the post-Lehman stimulus. It is a torrid pace even if you adjust for the declining velocity of money. The figure for China is an explosive 45pc (six-months annualized). Sooner or later, this surge of liquidity will lead to flickerings of inflation in the US, and then to the time-honoured inflationary take-off as the labour market tightens, at which point the markets will react and the global asset rally will short-circuit. The Atlanta Fed's gauge of 'sticky price inflation' for the US is running at 2.8pc. Wage growth has picked up to 2.6pc. Employers are having more trouble finding workers than at the peak of the last two booms. We are not at the danger line yet, but we are getting closer. Brexit was always a hoax for world markets. The financial cycle will end as it always has in peacetime over the last century: when the Fed tightens. "We suspect that an abrupt reassessment of the outlook for US monetary policy remains the key risk," says Capital Economics. Precisely. by Jeff Cox

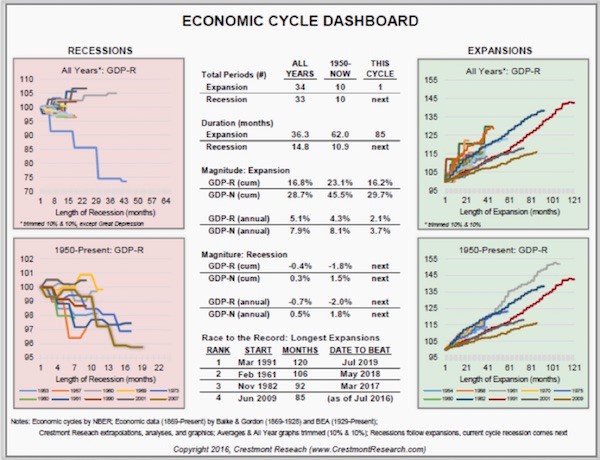

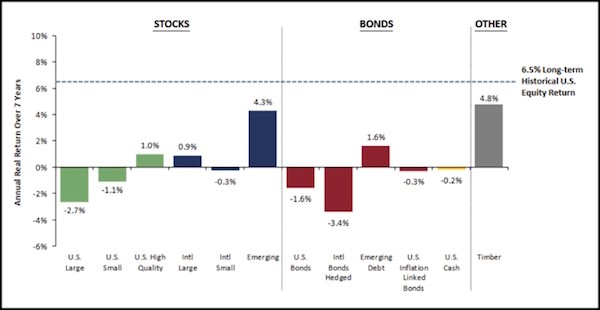

CNBC July 20, 2016 Corporate debt is projected to swell over the next several years, thanks to cheap money from global central banks, according to a report Wednesday that warns of a potential crisis from all that new, borrowed cash floating around. By 2020, business debt likely will climb to $75 trillion from its current $51 trillion level, according to S&P Global Ratings. Under normal conditions, that wouldn't be a major problem so long as credit quality stays high, interest rates and inflation remain low, and there are economic growth persists. However, the alternative is less pleasant should those conditions not persist. Should interest rates rise and economic conditions worsen, corporate America could be facing a major problem as it seeks to manage that debt. Rolling over bonds would become more difficult should inflation gain and rates raise, while a slowing economy would worsen business conditions and make paying off the debt more difficult. In that case, a "Crexit," or withdrawal by lenders from the credit markets, could occur and lead to a sudden tightening of conditions that could trigger another financial scare. "A worst-case scenario would be a series of major negative surprises sparking a crisis of confidence around the globe," S&P said in the report. "These unforeseen events could quickly destabilize the market, pushing investors and lenders to exit riskier positions ('Crexit' scenario). If mishandled, this could result in credit growth collapsing as it did during the global financial crisis." In fact, S&P considers a correction in the credit markets to be "inevitable." The only question is degree. The firm worries that investors have been overly willing in their hunt for yield to buy speculative-grade corporate debt. This has been true not only in the United States but also China, which has used borrowing to spur growth but now finds itself at an economic crossroads. Despite the debt boom, central banks have been loathe to put on the brakes. Interest rates remain low around the world, generating a boom in both corporate and government debt, with nearly $12 trillion of the latter now carrying negative yields. "Central banks remain in thrall to the idea that credit-fueled growth is healthy for the global economy," S&P said. "In fact, our research highlights that monetary policy easing has thus far contributed to increased financial risk, with the growth of corporate borrowing far outpacing that of the global economy." Between now and 2020, debt "flow" is expected to grow by $62 trillion — $38 trillion in refinancing and $24 trillion in new debt, including bonds, loans and other forms. That projection is up from the $57 trillion in new flow S&P had expected for the same period a year ago. As the debt market reaches its limits, the firm believes the most likely scenario is an orderly drawdown. However, that projection faces risks. "Alternatively, a worst-case scenario comprising several negative economic and political shocks (such as a potential fallout from Brexit) could unnerve lenders, causing them to pull back from extending credit to higher-risk borrowers," the report said. "Indeed, the credit build-up has generated two key tail risks for global credit. Debt has piled up in China's opaque and ever-expanding corporate sector and in U.S. leveraged finance. We expect the tail risks in these twin debt booms to persist." There's a significant risk in credit quality. Close to half of companies outside the financial sector are considered "highly leveraged," which is the lowest category for risk, and up to 5 percent of that group has negative earnings or cash flows. There already have been 100 debt defaults in 2016, the most since the financial crisis for the period. S&P worries that investors, particularly those that have bought bonds with longer duration in an effort to get higher yield, are at risk. "Favorable financing conditions, such as abundant debt funding and low interest rates, have elevated prices for financial assets as investors searched for yield," the report said. "This creates conditions for greater market volatility over the next few years due to lower secondary-market liquidity, with credit spreads for riskier credits and longer duration assets being most exposed." China is expected to account for the bulk of the credit flow growth, with the nation projected to add $28 trillion or 45 percent of the $62 trillion expected global demand increase. The U.S. is estimated to add $14 trillion or 22 percent, with Europe adding $9 trillion, or 15 percent. by John Mauldin July 16, 2016 The Age of No Returns The enemy is coming. Having absorbed Japan to the west and Europe to the east, negative interest rates now threaten North America from both directions. The vast oceans that protect us from invasions won’t help this time. Someday I want to get someone to count the number of times I’ve mentioned central bank chiefs by name in this newsletter since I first began writing in 2000, and we should graph the mentions by month. I suspect we’ll find that the number spiked higher in 2007 and has remained at a high plateau ever since – if it has not climbed even higher. That’s our problem in a nutshell. We shouldn’t have to talk about central banks and their leaders every time we discuss the economy. Monetary policy is but one factor in the grand economic equation and should certainly not be the most important one. Yet the Fed and its fellow central banks have been hogging center stage for nearly a decade now. That might be okay if their policies made sense, but abundant evidence says they do not. Overreliance on low interest rates to stimulate growth led our central bankers to zero interest rates. Failure of zero rates led them to negative rates. Now negative rates aren’t working, so their ploy is to go even more negative and throw massive quantitative easing and deficit financing at the balky global economy. Paul Krugman is beating the drum for more radical Keynesianism as loudly as anyone. He has a legion of followers. Unfortunately, they are in control in the halls of monetary policy power. Our central banks are one-trick ponies. They do their tricks well, but no one is applauding, except the adherents of central bank philosophy. Those of us who live in the real economy are growing increasingly restive. Today we’ll look at a few of the big problems that the Fed and its ilk are creating. As you’ll see, I think we are close to the point in the US where a significant course change might help, because our fate is increasingly locked in. I believe Europe and Japan have passed the point of no return. That means we should shift our thinking toward defensive measures. The Big Conundrum The immediate Brexit shock is passing, for now, but Europe is still a minefield. The Italian bank situation threatens to blow up into another angry stand-off like Greece, with much larger amounts at stake. The European Central Bank’s grand plans have not brought Southern Europe back from depression-like conditions. I cannot state this strongly enough: Italy is dramatically important, and it is on the brink of a radical break with European Union policy that will cascade into countries all over Europe and see them going their own way with regard to their banking systems. Italian politicians cannot allow Italian citizens to lose hundreds of billions, if not trillions, of euros to bank “bail-ins.” Such losses would be an utter disaster for Italy, resulting in a deflationary depression not unlike Greece’s. Of course, for the Italians to bail out their own banks, th ey will have to run their debt-to-GDP ratio up to levels that look like Greece’s. Will the ECB step in and buy Italy’s debt and keep their rates within reason? Before or after Italy violates ECB and EU policy? The Brexit vote isn’t directly connected to the banking issue, but it is still relevant. It has emboldened populist movements in other countries and forced politicians to respond. The usual Brussels delay tactics are losing their effectiveness. The associated uncertainty is showing itself in ever-lower interest rates throughout the Continent. That’s the situation to America’s east. On our western flank, Japan had national elections last weekend. Voters there do not share the anti-establishment fever that grips the rest of the developed world. They gave Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his allies a solid parliamentary majority. Japanese are either happy with the Abenomics program or see no better alternative. His expanded majority may give Abe the backing he needs to revise Japan’s constitution and its official pacifism policy. Doing so would be less a sign of nationalism than a new economic stimulus tool. Defense spending that more than doubles – as it is expected to do – will give a major boost to Japan’s shipyards, vehicle manufacturing, and electronics industries. The Bank of Japan’s negative-rate policy and gargantuan bond-buying operation will now continue full force and may even grow. Whether the program works or not is almost beside the point. It shows the government is “doing something” and suppresses the immediate symptoms of economic malaise. The Bank of Japan is the Japanese bond market. They are buying everything that comes available, and this year they will need to cough up an extra ¥40 trillion ($400 billion) just to make their purchase target, let alone increase their quantitative easing in the desperate attempt to drive up inflation. What is happening is that foreign speculators are becoming some of the largest holders of Japanese bonds, and many Japanese pension funds and other institutions are required to hold those bonds, so they aren’t selling. The irony is that the government is producing only about half the quantity of bonds the Bank of Japan wants to buy. Sometime this year the BOJ is going to have to do something differently. The question is, what? Okay, for you conspiracy theorists, please note that “Helicopter Ben” Bernanke was just in Japan and had private meetings with both Prime Minister Abe and Kuroda, who heads the Bank of Japan. Given the limited availability of bonds for the BOJ to buy, and that they’ve already bought a significant chunk of equities and other nontraditional holdings for a central bank, what are their other options? Perhaps Japan could authorize the BOJ to issue very-low-interest perpetual bonds to take on a significant portion of the Japanese debt. That option has certainly been a topic of discussion. It’s not exactly clear how you get people to give up their current debt when they don’t want to, or maybe the BOJ just forces them to swap out their old bonds for the new perpetual bonds, which would be on the balance sheet of the Bank of Japan and not counted as government debt. That’s one way to get rid of your debt problem. But that doesn’t give Abe and Kuroda the inflation they desperately want. Putting on my tinfoil hat (Zero Hedge should love this), the one country that could lead the way in actually experimenting with a big old helicopter drop of money into individual pockets is Japan. And Ben was just there… This bears watching. Okay, I am now removing my tinfoil hat. Yellen Changes the NIRP Tune I have been saying on the record for some time that I think it is really possible that the Fed will push rates below zero when the next recession arrives. I explained at length a few months ago in “The Fed Prepares to Dive.” In that regard, something important happened recently that few people noticed. I’ll review a little history in order to explain. In Congressional testimony last February, a member of Congress asked Janet Yellen if the Fed had legal authority to use negative interest rates. Her answer was this: In the spirit of prudent planning we always try to look at what options we would have available to us, either if we needed to tighten policy more rapidly than we expect or the opposite. So we would take a look at [negative rates]. The legal issues I'm not prepared to tell you have been thoroughly examined at this point. I am not aware of anything that would prevent [the Fed from taking interest rates into negative territory]. But I am saying we have not fully investigated the legal issues. So as of then, Yellen had no firm answer either way. A few weeks later she sent a letter to Rep. Brad Sherman (D-CA), who had asked what the Fed intended to do in the next recession and if it had authority to implement negative rates. She did not directly answer the legality question, but Bloomberg reported at the time (May 12) that Rep. Sherman took the response to mean that the Fed thought it had the authority. Yellen noted in the letter that negative rates elsewhere seemed to be having an effect. (I agree that they are having an effect; it’s just that I don’t think the effect is a good one.) Fast-forward a few more weeks to Yellen’s June 21 congressional appearance. She took us further down the rabbit hole, stating flatly that the Fed does have legal authority to use negative rates, but denying any intent to do so. “We don't think we are going to have to provide accommodation, and if we do, [negative rates] is not something on our list,” Yellen said. That denial came two days before the Brexit vote, which we now know from FOMC minutes had been discussed at a meeting the week earlier. But I’m more concerned about the legal authority question. If we are to believe Yellen’s sworn testimony to Congress, we know three things: 1. As of February, Yellen had not “fully investigated” the legal issues of negative rates. 2. As of May, Yellen was unwilling to state the Fed had legal authority to go negative. 3. As of June, Yellen had no doubt the Fed could legally go negative. When I wrote about this back in February, I said the Fed’s legal staff should all be disbarred if they hadn’t investigated these legal issues. Clearly they had. Bottom line: by putting the legal authority question to rest, the Fed is laying the groundwork for taking rates below zero. And I’m sure Yellen was telling the truth when she said last month that they had no such plan. Plans can change. The Fed always tells us they are data-dependent. If the data says we are in recession, I think it is very possible the Fed will turn to negative rates to boost the economy. Except, in my opinion, it won’t work. When Average Is Zero Now, I am not suggesting the Fed will push rates negative this month or even this year – but they will do it eventually. I’ll be surprised if it doesn’t happen by the end of 2018. A prime reason the next recession will be severe is that we never truly recovered from the last one. My friend Ed Easterling of Crestmont Research just updated his Economic Cycle Dashboard and sent me a personal email with some of his thoughts. Here is his chart (click on it to see a larger version). The current expansion is the fourth-longest one since 1954 but also the weakest one. Since 1950, average annual GDP growth in recovery periods has been 4.3%. This time around, average GDP growth has been only 2.1% for the seven years following the Great Recession. That means the economy has grown a mere 16% during this so-called “recovery” (a term Ed says he plans to avoid in the future). If this were an average recovery, total GDP growth would have been 34% by now instead of 16%. So it’s no wonder that wage growth, job creation, household income, and all kinds of other stats look so meager. For reasons I have outlined elsewhere and will write more about in the future, I think the next recovery will be even weaker than the current one, which is already the weakest in the last 60 years – precisely because monetary policy is hindering growth. Now combine a weak recovery with NIRP. If, in the long run, asset prices are a reflection of interest rates and economic growth, and both those are just slightly above or below zero, can we really expect stocks, commodities, and other assets to gain value? The upshot is that whatever traditional investment strategy you believe in will probably stop working soon. Ask European pension and insurance companies that are forced to try to somehow materialize returns in a non-return world of negative interest rates. All bets may be off anyway if the latest long-term return forecasts are correct. Here’s GMO’s latest 7-year asset class forecast: See that dotted line, the one that not a single asset class gets anywhere near? That’s the 6.5% long-term stock return that many supposedly wise investors tell us is reasonable to expect. GMO doesn’t think it’s reasonable at all, at least not for the next seven years.

If GMO is right – and they usually are – and you’re a devotee of any kind of passive or semi-passive asset allocation strategy, you can expect somewhere around 0% returns over the next seven years – if you’re lucky. Note also that nearly invisible -0.2% yellow bar for “U.S. Cash.” Negative multi-year real (adjusted for inflation) returns from cash? You bet. Welcome to NIRP, American-style. Would you like that with fries? The Fed’s fantasies notwithstanding, NIRP is not conducive to “normal” returns in any asset class. GMO says the best bets are emerging-market stocks and timber. Those also happen to be thin markets that everyone can’t hold at once. So, prepare to be stuck. by George Friedman

Geopolitical Futures July 8, 2016 The Italian banking crisis is not only Italy’s problem. We are now at the point where the mainstream media has recognized that there is an Italian banking crisis. As we have been arguing since December, when we published our 2016 forecast, Italy’s crisis will be a dominant feature of the year. Italy has actually been in a crisis for at least six months. This crisis has absolutely nothing to do with Brexit, although opponents of Brexit will claim it does. Even if Britain had unanimously voted to stay in the EU, the Italian crisis would still have been gathering speed. The extraordinarily high level of non-performing loans (NPLs) has been a problem since before Brexit, and it is clear that there is nothing in the Italian economy that will allow it to be reduced. A non-performing loan is simply a loan that isn’t being repaid according to terms, and the reason this happens is normally the inability to repay it. Only a dramatic improvement in the economy would make it possible to repay these loans, and Europe’s economy cannot improve drastically enough to help. We have been in crisis for quite a while. The crisis was hidden, in a way, because banks were simply carrying loans as non-performing that were actually in default and discounting the NPLs rather than writing them off. But that simply hid the obvious. As much as 17 percent of Italy’s loans will not be repaid. As a result, the balance sheets of Italian banks will be crushed. And this will not only be in Italy. Italian loans are packaged and resold as others, and Italian banks take loans from other European banks. These banks in turn have borrowed against Italian debt. Since Italy is the fourth largest economy in Europe, this is the mother of all systemic threats. Since the problem is insoluble, the only way to help is a government bailout. The problem is that Italy is not only part of the EU, but part of the eurozone. As such, its ability to print its way out of the crisis is limited. In addition, EU regulations make it difficult for governments to bail out banks. The EU has a concept called a bail-in, which is a cute way of saying that the depositors and creditors to the bank will lose their money. This is what the EU imposed on Cyprus. In Cyprus, deposits greater than 100,000 euros ($111,000) were seized to cover Cypriot bank debts. While some was returned, most was not. The depositors discovered that the banks, rather than being a safe haven for money, were actually fairly risky investments. The bail-in is, of course, a formula for bank runs. The money seized in Cyprus came from retirement funds and bank payrolls. The Italian government is trying to make certain that depositors don’t lose their deposits because a run on the banks would guarantee a meltdown. A meltdown would topple the government and allow the Five Star Movement, an anti-European party, a good shot at governing. The reason for the bail-in rule is Berlin’s aversion to bailing out banking systems using German money. Germany is already seeing a rise in anti-European political feeling with the rising popularity of the nationalist Alternative for Germany party. Unlike Italian anti-European sentiment, the German sense of victimization is their perception that they are disciplined and responsible, and they resent paying for the irresponsibility of others. Therefore, the German government’s hands are tied. It cannot accept a Europe-wide deposit insurance system as it would put German money at risk, nor can it permit the euro to be printed promiscuously, as that would come out of the German hide as well. The Italians can only try and manage the problem by ignoring EU rules, which is what they are actually doing. But there is another European economic crisis brewing. As we have pointed out, Germany derives nearly half of its GDP from exports. All the discipline and frugality of the Germans can’t hide the fact that their prosperity depends on their ability to export and that the ability to export depends on the effective demand of their customers. Germany exports heavily to the EU, and the Italian crisis, if it proceeds as it is going, is likely to cause an EU-wide banking crisis, and an even greater weakening of the European economy. That would cut deeply into German exports, slashing GDP and inevitably driving up unemployment. Logic would have it that the Germans are acting desperately to head off an Italian default, but Chancellor Angela Merkel has built her government on Germany’s pride in its economy. She is not eager to announce to the German people that the German economy depends on Italy’s well-being. But it is clear that German businesses are aware of the danger. German production of capital goods fell nearly 4 percent from last month, and German production of consumer goods rose only 0.5 percent. German consumption can’t possibly make up for half of Germany’s GDP. In addition, the International Monetary Fund has recently pointed to Deutsche Bank as the single largest contributor to systemic risk in the world. A rippling default through Europe is going to hit Deutsche Bank. However, the real threat to Germany is a U.S. recession. Recessions are normal, cyclical events that are necessary to maintain economic efficiency by culling inefficient businesses. The U.S. has one on average once every six to seven years. Substantial irrationality has crept into the economy, including new bubbles in housing. The yield curve on interest rates is beginning to flatten. Normally, a major market decline precedes a recession by three to six months. That would indicate that there likely won’t be a recession in 2016 but there is a reasonable chance of one in 2017. Given the stagnation in Europe, Germany has been shifting its exports to other countries, particularly the United States. It is hard to tell how much price cutting the Germans had to do to increase their exports, but it has been useful to maintain the amount of GDP derived from exports. If the United States goes into recession, demand for German goods, among others, will drop. But in the case of Germany, a 1 percent drop in exports is nearly a half percent drop in GDP. And given Germany’s minimal growth rate, drops of a few percentage points could drive it not only into recession, but into its primordial fear: high unemployment. A U.S. recession would not only hit the Germans, but the rest of Europe, which also exports to the United States, either directly or through producing components for German and British products. When we look at data on U.S. exposure to foreign debt defaults, there is some, but not enough to bring down the American system. The United States, with relatively low export percentages and low exposure, can withstand its cycle. It is not clear that Europe can. Compounding this problem is an ever-increasing number of non-performing loans in China. Most of these are domestic loans, but they reflect the fact that China has never recovered from the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. It has avoided massive social dislocation by encouraging loans to businesses of all sizes and dubious viability in order to maintain employment as far as possible. There is a new wave of non-performing loans coming due. And as with Italy, non-performing is a euphemism. The problem is not that these loans are late. The problem is that they were loaned to businesses and individuals who should have been forced out of business by a lack of credit, and were kept alive on artificial respirators. The obsession of figures like European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, railing against Brexit, was not a smokescreen. He and others really did see Brexit as the major danger to the EU. That is what is most troubling. Far more significant are Italy’s financial crisis and Germany’s extreme vulnerability. Whether the British stay or go, Italy’s and Germany’s problems have to be addressed, and the existence of the EU and its regulations make finding solutions extremely difficult. This all was put in motion in 2008, but it is not a 2008 crisis. This is most of all a political and administrative crisis caused by a European system that was created to administer peace and prosperity, not to manage the complex gyrations of an economy. Similarly, China introduced the doctrine of enriching yourself to please the Party, but hadn’t considered what to do when the party was over. The argument from those who are against internationalism is simple. Sometimes the major international systems begin failing. The less you are entangled with these systems the less damage is done to you. And given that such systemic failures historically lead to international political conflict and crisis, the case for nationalism increases – assuming you aren’t already trapped in the systemic crisis. In any event, increasing nationalism follows systemic failure like night follows day. by Bill Gross

Janus Capital July 6, 2016 If only Fed Governors and Presidents understood a little bit more about Monopoly, and a tad less about outdated historical models such as the Taylor Rule and the Phillips Curve, then our economy and its future prospects might be a little better off. That is not to say that Monopoly can illuminate all of the problems of our current economic stagnation. Brexit and a growing Populist movement clearly point out that the possibility of de-globalization (less trade, immigration and economic growth) is playing a part. And too, structural elements long ago advanced in my New Normal thesis in 2009 have a significant role as well: aging demographics, too much debt, and technological advances including job-threatening robotization are significantly responsible for 2% peak U.S. real GDP as opposed to 4-5% only a decade ago. But all of these elements are but properties on a larger economic landsc ape best typified by a Monopoly board. In that game, capitalists travel around the board, buying up properties, paying rent, and importantly passing “Go” and collecting $200 each and every time. And it’s the $200 of cash (which in the economic scheme of things represents new “credit”) that is responsible for the ongoing health of our finance-based economy. Without new credit, economic growth moves in reverse and individual player “bankruptcies” become more probable. But let’s start back at the beginning when the bank hands out cash, and each player begins to roll the dice. The bank – which critically is not the central bank but the private banking system– hands out $1,500 to each player. The object is to buy good real estate at a cheap price and to develop properties with houses and hotels. But the player must have a cash reserve in case she lands on other properties and pays rent. So at some point, the process of economic development represented by the building of houses and hotels slows down. You can’t just keep buying houses if you expect to pay other players rent. You’ll need cash or “credit”, and you’ve spent much of your $1,500 buying properties. To some extent, growth for all the players in general can continue but at a slower pace – the economy slows down due to a more levered position for each player but still grows because of the $200 that each receives as he passes Go. But here’s the rub. In Monopoly, the $200 of credit creation never changes. It’s always $200. If the rules or the system allowed for an increase to $400 or say $1,000, then players could keep on building and the economy keep growing without the possibility of a cash or credit squeeze. But it doesn’t. The rules which fix the passing “Go” amount at $200 ensure at some point the breakdown of a player who hasn’t purchased “well” or reserved enough cash. Bankruptcies begin. The Monopoly game, which at the start was so exciting as $1,500 and $200 a pass made for asset accumulation and economic growth, now tur ns sullen and competitive: Dog eat dog with the survival of many of the players on the board at risk. All right. So how is this relevant to today’s finance-based economy? Hasn’t the Fed printed $4 trillion of new money and the same with the BOJ and ECB? Haven’t they effectively increased the $200 “pass go” amount by more than enough to keep the game going? Not really. Because in today’s modern day economy, central banks are really the “community chest”, not the banker. They have lots and lots of money available but only if the private system – the economy’s real bankers – decide to use it and expand “credit”. If banks don’t lend, either because of risk to them or an unwillingness of corporations and individuals to borrow money, then credit growth doesn’t increase. The system still generates $200 per player per round trip roll of the dice, but it’s not enough to keep real GDP at the same pace and to prevent some companies/households from going bankrupt. That is what’s happening today and has been happening for the past few years. As shown in Chart I, credit growth which has averaged 9% a year since the beginning of this century barely reaches 4% annualized in most quarters now. And why isn’t that enough? Well the proof’s in the pudding or the annualized GDP numbers both here and abroad. A highly levered economic system is dependent on credit creation for its stability and longevity, and now it is growing sub-optimally. Yes, those structural elements mentioned previously are part of the explanation. But credit is the oil that lubes the system, the straw that stirs the drink, and when the private system (not the central bank) fails to generate sufficient credit growth, then real economic growth stalls and even goes in reverse. (To elaborate just slightly, total credit, unlike standard “money supply” definitions include all credit or debt from households, businesses, government, and finance-based sources. It now totals a staggering $62 trillion in contrast to M1/M2 totals which approximate $13 trillion at best.) Now many readers may be familiar with the axiomatic formula of (“M V = PT”), which in plain English means money supply X the velocity of money = PT or Gross Domestic Product (permit me the simplicity for sake of brevity). In other words, money supply or “credit” growth is not the only determinant of GDP but the velocity of that money or credit is important too. It’s like the grocery store business. Turnover of inventory is critical to profits and in this case, turnover of credit is critical to GDP and GDP growth. Without elaboration, because this may be getting a little drawn out, velocity of credit is enhanced by lower and lower interest rates. Thus, over the past 5-6 years post-Lehman, as the private system has created insufficient credit growth, the lower and lower interest rates have increased velocity and therefore increased GDP, although weakly. No w, however with yields at near zero and negative on $10 trillion of global government credit, the contribution of velocity to GDP growth is coming to an end and may even be creating negative growth as I’ve argued for the last several years. Our credit-based financial system is sputtering, and risk assets are reflecting that reality even if most players (including central banks) have little clue as to how the game is played. Ask Janet Yellen for instance what affects the velocity of credit or even how much credit there is in the system and her hesitant answer may not satisfy you. They don’t believe in Monopoly as the functional model for the modern day financial system. They believe in Taylor and Phillips and warn of future inflation as we approach “full employment”. They worship false idols. To be fair, the fiscal side of our current system has been nonexistent. We’re not all dead, but Keynes certainly is. Until governments can spend money and replace the animal spirits lacking in the private sector, then the Monopoly board and meager credit growth shrinks as a future deflationary weapon. But investors should not hope unrealistically for deficit spending any time soon. To me, that means at best, a ceiling on risk asset prices (stocks, high yield bonds, private equity, real estate) and at worst, minus signs at year’s end that force investors to abandon hope for future returns compared to historic examples. Worry for now about the return “of” your money, not the return “on” it. Our Monopoly-based economy requires credit creation and if it stays low, the future losers will grow in number. by Bill Gross

Janus Capital June 2, 2016 The economist Joseph Schumpeter once remarked that the “top-dollar rooms in capitalism’s grand hotel are always occupied, but not by the same occupants”. There are no franchises, he intoned — you are king for a figurative day, and then — well — you move to another room in the castle; hopefully not the dungeon, which is often the case. While Schumpeter’s observation has obvious implications for one and all, including yours truly, I think it also applies to markets, various asset classes, and what investors recognize as “carry”. That shall be my topic of the day, as I observe the Pacific Ocean from Janus’ fourteenth floor — not exactly the penthouse but there is space available on the higher floors, and I have always loved a good view. Anyway, my basic thrust in this Outlook will be to observe that all forms of “carry” in financial markets are compressed, resulting in artificially high asset prices and a distortion of future risk relative to potential return that an investor must confront. Experienced managers that have treaded markets for several decades or more recognize that their “era” has been a magnificent one despite many “close calls” characterized by Lehman, the collapse of NASDAQ 5000, the Savings + Loan crisis in the early 90’s, and so on. Chart 1 proves the point for bonds. Since the inception of the Barclays Capital U.S. Aggregate or Lehman Bond index in 1976, investment grade bond markets have provided conservative investors with a 7.47% compound return with remarkably little volatility. An observer of the graph would be amazed, as was I, at the steady climb of wealth, even during significant bear markets when 30-year Treasury yields reached 15% in the early 80’s and were tagged with the designation of “certificates of confiscation”. The graph proves otherwise, because as bond prices were going down, the hig her and higher annual yields smoothed the damage and even led to positive returns during “headline” bear market periods such as 1979-84, or more recently the “taper tantrum” of 2013. Quite remarkable, isn’t it? A Sherlock Holmes sleuth interested in disproving this thesis would find few 12-month periods of time where the investment grade bond market produced negative returns. The path of stocks has not been so smooth but the annual returns (with dividends) have been over 3% higher than investment grade bonds as Chart 2 shows. That is how it should be: stocks displaying higher historical volatility but more return. But my take from these observations is that this 40-year period of time has been quite remarkable – a grey if not black swan event that cannot be repeated. With interest rates near zero and now negative in many developed economies, near double digit annual returns for stocks and 7%+ for bonds approach a 5 or 6 Sigma event, as nerdish market technocrats might describe it. You have a better chance of observing another era like the previous 40-year one on the planet Mars than you do here on good old Earth. The “top dollar rooms in the financial market’s grand hotel” may still be occupied by attractive relative asset classes, but the room rate is extremely high and the view from the penthouse is shrouded in fog, which is my meteorological metaphor for high risk. Let me borrow some excellent work from another investment firm that has occupied the upper floors of the market’s grand hotel for many years now. GMO’s Ben Inker in his first quarter 2016 client letter makes the point that while it is obvious that a 10-year Treasury at 1.85% held for 10 years will return pretty close to 1.85%, it is not widely observed that the rate of return of a dynamic “constant maturity strategy” maintaining a fixed duration on a Barclays Capital U.S. Aggregate portfolio now yielding 2.17%, will almost assuredly return between 1.5% and 2.9% over the next 10 years, even if yields double or drop to 0% at period’s end. The bond market’s 7.5% 40-year historical return is just that – history. In order to duplicate that number, yields would have to drop to -17%! Tickets to Mars, anyone? The case for stocks is more complicated of course with different possibilities for growth, P/E ratios and potential government support in the form of “Hail Mary” QE’s now employed in Japan, China, and elsewhere. Equities though, reside on the same planet Earth and are correlated significantly to the return on bonds. Add a historical 3% “equity premium” to GMO’s hypothesis on bonds if you dare, and you get to a range of 4.5% to 5.9% over the next 10 years, and believe me, those forecasts require a foghorn warning given current market and economic distortions. Capitalism has entered a new era in this post-Lehman period due to unimaginable monetary policies and negative structural transitions that pose risk to growth forecasts and the historical linear upward slope of productivity. Here’s my thesis in more compact form: For over 40 years, asset returns and alpha generation from penthouse investment managers have been materially aided by declines in interest rates, trade globalization, and an enormous expansion of credit – that is debt. Those trends are coming to an end if only because in some cases they can go no further. Those historic returns have been a function of leverage and the capture of “carry”, producing attractive income and capital gains. A repeat performance is not only unlikely, it is impossible unless you are a friend of Elon Musk and you’ve got the gumption to blast off for Mars. Planet Earth does not offer such opportunities. “Carry” in almost all forms is compressed and offers more risk than potential return. I will be specific: • Duration is unquestionably a risk in negative yielding markets. A minus 25 basis point yield on a 5-year German Bund produces nothing but losses five years from now. A 45 basis point yield on a 30-year JGB offers a current “carry” of only 40 basis points per year for a near 30-year durational risk. That’s a Sharpe ratio of .015 at best, and if interest rates move up by just 2 basis points, an investor loses her entire annual income. Even 10-year U.S. Treasuries with a 125 basis point “carry” relative to current money market rates represent similar durational headwinds. Maturity extension in order to capture “carry” is hardly worth the risk. • Similarly, credit risk or credit “carry” offers little reward relative to potential losses. Without getting too detailed, the advantage offered by holding a 5-year investment grade corporate bond over the next 12 months is a mere 25 basis points. The IG CDX credit curve offers a spread of 75 basis points for a 5-year commitment but its expected return over the next 12 months is only 25 basis points. An investor can only earn more if the forward credit curve – much like the yield curve – is not realized. • Volatility. Carry can be earned by selling volatility in many areas. Any investment longer or less creditworthy than a 90-day Treasury Bill sells volatility whether a portfolio manager realizes it or not. Much like the “VIX®”, the Treasury “Move Index” is at a near historic low, meaning there is little to be gained by selling outright volatility or other forms in duration and credit space. • Liquidity. Spreads for illiquid investments have tightened to historical lows. Liquidity can be measured in the Treasury market by spreads between “off the run” and “on the run” issues – a spread that is nearly nonexistent, meaning there is no “carry” associated with less liquid Treasury bonds. Similar evidence exists with corporate CDS compared to their less liquid cash counterparts. You can observe it as well in the “discounts” to NAV or Net Asset Value in closed-end funds. They are historically tight, indicating very little “carry” for assuming a relatively illiquid position. The “fact of the matter” – to use a politician’s phrase – is that “carry” in any form appears to be very low relative to risk. The same thing goes with stocks and real estate or any asset that has a P/E, cap rate, or is tied to present value by the discounting of future cash flows. To occupy the investment market’s future “penthouse”, today’s portfolio managers – as well as their clients, must begin to look in another direction. Returns will be low, risk will be high and at some point the “Intelligent Investor” must decide that we are in a new era with conditions that demand a different approach. Negative durations? Voiding or shorting corporate credit? Buying instead of selling volatility? Staying liquid with large amounts of cash? These are all potential “negative” carry positions tha t at some point may capture capital gains or at a minimum preserve principal. But because an investor must eat something as the appropriate reversal approaches, the current penthouse room service menu of positive carry alternatives must still be carefully scrutinized to avoid starvation. That means accepting some positive carry assets with the least amount of risk. Sometime soon though, as inappropriate monetary policies and structural headwinds take their toll, those delicious “carry rich and greasy” French fries will turn cold and rather quickly get tossed into the garbage can. Bon Appetit! |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed