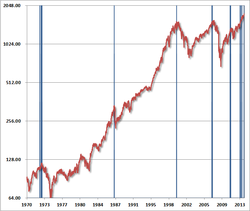

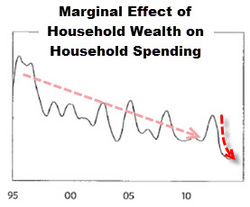

We feature John Hussman in this blog from time to time, not just because we are fans of his disciplined empricial approach to investing (and that we are) but more recently because he has been one of the few voices in highlighting the significant tail risk embedded in the US stock market founded on a belief in the omniscience of the Fed and their QE program. Lionscrest provides protection against the tail events; arguably, there has never been a greater need for this type of protection. - Editor ----- A Textbook Pre-Crash Bubble (link to website) John P. Hussman, Ph.D. November 11, 2013 Investors who believe that history has lessons to teach should take our present concerns with significant weight, but should also recognize that tendencies that repeatedly prove reliable over complete market cycles are sometimes defied over portions of those cycles. Meanwhile, investors who are convinced that this time is different can ignore what follows. The primary reason not to listen to a word of it is that similar concerns, particularly since late-2011, have been followed by yet further market gains. If one places full weight on this recent period, and no weight on history, it follows that stocks can only advance forever. What seems different this time, enough to revive the conclusion that “this time is different,” is faith in the Federal Reserve’s policy of quantitative easing. Though quantitative easing has no mechanistic relationship to stock prices except to make low-risk assets psychologically uncomfortable to hold, investors place far more certainty in the effectiveness of QE than can be demonstrated by either theory or evidence. The argument essentially reduces to a claim that QE makes stocks go up because “it just does.” We doubt that the perception that an easy Fed can hold stock prices up will be any more durable in the next couple of years than it was in the 2000-2002 decline or the 2007-2009 decline – both periods of persistent and aggressive Fed easing. But QE is novel, and like the internet bubble, novelty feeds imagination. Most of what investors believe about QE is imaginative. As Ray Dalio of Bridgwater recently observed, “The dilemma the Fed faces now is that the tools currently at its disposal are pretty much used up. We think the question around the effectiveness of QE (and not the tapering, which gets all the headlines) is the big deal. In other words, we’re not worried about whether the Fed is going to hit or release the gas pedal, we’re worried about whether there’s much gas left in the tank and what will happen if there isn’t.” While we can make our case on the basis of fact, theory, data, history, and sometimes just basic arithmetic, what we can’t do – and haven’t done well – is to disabuse perceptions. Beliefs are what they are, and are only as malleable as the minds that hold them. Like the nearly religious belief in the technology bubble, the dot-com boom, the housing bubble, and countless other bubbles across history, people are going to believe what they believe here until reality catches up in the most unpleasant way. The resilience of the market late in a bubble is part of the reason investors keep holding and hoping all the way down. In this market cycle, as in all market cycles, few investors will be able to unload their holdings to the last of the greater fools just after the market’s peak. Instead, most investors will hold all the way down, because even the initial decline will provoke the question “how much lower could it go?” It has always been that way. The problem with bubbles is that they force one to decide whether to look like an idiot before the peak, or an idiot after the peak. There’s no calling the top, and most of the signals that have been most historically useful for that purpose have been blaring red since late-2011. As a result, the Shiller P/E (the S&P 500 divided by the 10-year average of inflation-adjusted earnings) is now above 25, a level that prior to the late-1990’s bubble was seen only in the three weeks prior to the 1929 peak. Meanwhile, the price/revenue ratio of the S&P 500 is now double its pre-bubble norm, as is the ratio of stock market capitalization to GDP. Indeed, the median price/revenue ratio of the S&P 500 is actually above the 2000 peak – largely because small cap stocks were much more reasonably priced in 2000 than they are today (not that those better relative valuations prevented wicked losses in small caps during the 2000-2002 decline). Despite the unusually extended period of speculation as a result of faith in quantitative easing, I continue to believe that normal historical regularities will exert themselves with a vengeance over the completion of this market cycle. Importantly, the market has now re-established the most hostile overvalued, overbought, overbullish syndrome we identify. Outside of 2013, we’ve observed this syndrome at only 6 other points in history: August 1929 (followed by the 85% market decline of the Great Depression), November 1972 (followed by a market plunge in excess of 50%), August 1987 (followed by a market crash in excess of 30%), March 2000 (followed by a market plunge in excess of 50%), May 2007 (followed by a market plunge in excess of 50%), and January 2011 (followed by a market decline limited to just under 20% as a result of central bank intervention). These concerns are easily ignored since we also observed them at lower levels this year, both in February (see A Reluctant Bear’s Guide to the Universe) and in May. Still, the fact is that this syndrome of overvalued, overbought, overbullish, rising-yield conditions has emerged near the most significant market peaks – and preceded the most severe market declines – in history: 1. S&P 500 Index overvalued, with the Shiller P/E (S&P 500 divided by the 10-year average of inflation-adjusted earnings) greater than 18. The present multiple is actually 25. 2. S&P 500 Index overbought, with the index more than 7% above its 52-week smoothing, at least 50% above its 4-year low, and within 3% of its upper Bollinger bands (2 standard deviations above the 20-period moving average) at daily, weekly, and monthly resolutions. Presently, the S&P 500 is either at or slightly through each of those bands. 3. Investor sentiment overbullish (Investors Intelligence), with the 2-week average of advisory bulls greater than 52% and bearishness below 28%. The most recent weekly figures were 55.2% vs. 15.6%. The sentiment figures we use for 1929 are imputed using the extent and volatility of prior market movements, which explains a significant amount of variation in investor sentiment over time. 4. Yields rising, with the 10-year Treasury yield higher than 6 months earlier. The blue bars in the chart to the right depict the complete set of instances since 1970 when these conditions have been observed.  In the old days central banks moved interest rates to run monetary policy. By watching the flows, we could see how lowering interest rates stimulated the economy by 1) reducing debt service burdens which improved cash flows and spending, 2) making it easier to buy items marked on credit because the monthly payments declined, which raised demand (initially for interest rate sensitive items like durable goods and housing) and 3) producing a positive wealth effect because the lower interest rate would raise the present value of most investment assets (and we saw how raising interest rates has had the opposite effect). All that changed when interest rates hit 0%; "printing money" (QE) replaced interest-rate changes. Because central banks can only buy financial assets, quantitative easing drove up the prices of financial assets and did not have as broad of an effect on the economy. The Fed's ability to stimulate the economy became increasingly reliant on those who experience the increased wealth trickling it down to spending and incomes, which happened in decreasing degrees (for logical reasons, given who owned the assets and their decreasing marginal propensities to consume). As shown in the chart on the right, the marginal effects of wealth increases on economic activity have been declining significantly. The Fed's dilemma is that its policy is creating a financial market bubble that is large relative to the pickup in the economy that it is producing. If it were targeting asset prices, it would tighten monetary policy to curtail the emerging bubble, whereas if it were targeting economic conditions, it would have a slight easing bias. In other words, 1) the Fed is faced with a difficult choice, and 2) it is losing its effectiveness. By Mark Spitznagel

November 4, 2013 Forbes Magazine In the midst of the epic dysfunction known as the 16-day government shutdown, we lost sight of the fundamental issue whose inescapable logic cuts across politics and party lines: We are feeding the rapacious appetites of our current selves (we want what we want now) at the dire and escalating cost to our future selves (whom, we assume, will somehow have the patience and resources to bear the burden). If that sounds unworkable and unsustainable, it is. If government spending continues apace, feeding the monster known as the national debt will swallow the resources of our future selves, whether we personify that concept as ourselves at retirement or our children who will inherit an astronomical bill for our rash and compulsive spending. We cannot expect Washington to solve these problems, because politicians are, by definition, creatures of the moment who want to please their current constituents who will re-elect them, rather than worrying about future constituents who cannot vote. It’s up to us to advocate for our future selves, both personal and progeny. As simple and logical as this might sound, it is nigh onto impossible to do. We simply can’t help ourselves, because of our human nature and a behavioral concept—applicable to most everything in life, including my bailiwick of investing—called time inconsistency, or hyperbolic discounting. Simply stated, we discount the present now more than we expect to later—that is, we act one way now—impatient, demanding our appetites (food, drink, investment returns) be met at all costs—while deluding ourselves that, in the future, we’ll somehow be patient and better able to act rationally and take care of problems. But when later becomes now, we are just as impatient. The easiest and most universal example is dieting. We indulge now, telling ourselves we’ll diet tomorrow. The parallels to our bloated spending and ballooning debt are too obvious to mention. The root of the problem goes to our human origins, when overlooking immediate needs was reckless and life-threatening. Consider the 1.8-million-year-old pre-human skull unveiled recently, with its massive jaw and big teeth, but small brain. I’m certainly no expert in human evolution, but it doesn’t take much to imagine this ancestral precursor was more concerned about eating now than preparing for the future. Yet, humans did overcome that predilection, through making tools, domesticating animals, growing and storing grains, smelting ores and metals, and eventually amassing great entrepreneurial capital structures that required upfront investment and lost opportunity costs in the moment. This became possible because objectives switched, from satisfying immediate appetites to gaining an intermediate, positional advantage for the future. My shorthand phrase for that is becoming ever-more roundabout. Our only hope to stop the battle between present and future selves is to adopt a more roundabout perspective, seeing time differently in an intertemporal dimension. When we are no longer hyper-focused on the moment, we can pursue proximal aims that look across slices of time. We avoid eating, drinking, acting, and spending as if there is no tomorrow, so that we can, indeed, have better, healthier, and more prosperous tomorrow. Admittedly, grasping these concepts about our human nature and our perplexing time inconsistency requires a mental leap. By becoming more aware, though, we give ourselves a roadmap with which to navigate the minefields of our own human nature. With an intertemporal perspective we can avoid the mad scramble for 11th hour solutions, which in politics always equals crisis. Since we cannot expect Washington and its stable of political animals to do the work, we must press for it ourselves, by sending the message to Capitol Hill: Taking on ever bigger amounts of debt is mathematically unsustainable. Using the Federal Reserve and its zero-interest-rate policy to kick the proverbial can down the road only postpones the pain, which intensifies with the passage of time. The reckoning will be excruciating. When another shutdown looms in the months ahead, we have to keep in mind who the battle is really between: our present selves versus our future selves. We who can think, act, and vote now, must advocate for the currently disenfranchised who will pay the bill. Mark Spitznagel is the founder and President of Universa Investments, and author of The Dao of Capital: Austrian Investing in a Distorted World (Wiley, 2013). |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed