|

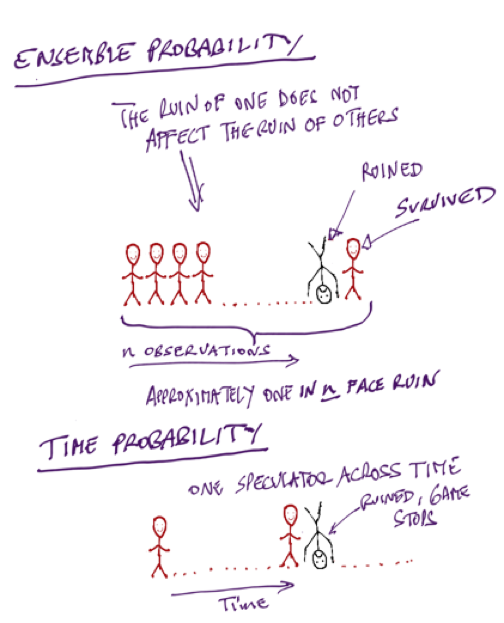

A central chapter from Taleb’s forthcoming book: Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb August 25, 2017 (unedited) Time to explain ergodicity, ruin and (again) rationality. Recall from the previous chapter that to do science (and other nice things) requires survival t not the other way around? Consider the following thought experiment. First case, one hundred persons go to a Casino, to gamble a certain set amount each and have complimentary gin and tonic –as shown in the cartoon in Figure x. Some may lose, some may win, and we can infer at the end of the day what the “edge” is, that is, calculate the returns simply by counting the money left with the people who return. We can thus figure out if the casino is properly pricing the odds. Now assume that gambler number 28 goes bust. Will gambler number 29 be affected? No. You can safely calculate, from your sample, that about 1% of the gamblers will go bust. And if you keep playing and playing, you will be expected have about the same ratio, 1% of gamblers over that time window. Now compare to the second case in the thought experiment. One person, your cousin Theodorus Ibn Warqa, goes to the Casino a hundred days in a row, starting with a set amount. On day 28 cousin Theodorus Ibn Warqa is bust. Will there be day 29? No. He has hit an uncle point; there is no game no more. No matter how good he is or how alert your cousin Theodorus Ibn Warqa can be, you can safely calculate that he has a 100% probability of eventually going bust. The probabilities of success from the collection of people does not apply to cousin Theodorus Ibn Warqa. Let us call the first set ensemble probability, and the second one time probability (since one is concerned with a collection of people and the other with a single person through time). Now, when you read material by finance professors, finance gurus or your local bank making investment recommendations based on the long term returns of the market, beware. Even if their forecast were true (it isn’t), no person can get the returns of the market unless he has infinite pockets and no uncle points. The are conflating ensemble probability and time probability. If the investor has to eventually reduce his exposure because of losses, or because of retirement, or because he remarried his neighbor’s wife, or because he changed his mind about life, his returns will be divorced from those of the market, period. We saw with the earlier comment by Warren Buffett that, literally, anyone who survived in the risk taking business has a version of “in order to succeed, you must first survive.” My own version has been: “never cross a river if it is on average four feet deep.” I effectively organized all my life around the point that sequence matters and the presence of ruin does not allow cost-benefit analyses; but it never hit me that the flaw in decision theory was so deep. Until came out of nowhere a paper by the physicist Ole Peters, working with the great Murray Gell-Mann. They presented a version of the difference between the ensemble and the time probabilities with a similar thought experiment as mine above, and showed that about everything in social science about probability is flawed. Deeply flawed. Very deeply flawed. For, in the quarter millennia since the formulation by the mathematician Jacob Bernoulli, and one that became standard, almost all people involved in decision theory made a severe mistake. Everyone? Not quite: every economist, but not everyone: the applied mathematicians Claude Shannon, Ed Thorp, and the physicist J.-L. Kelly of the Kelly Criterion got it right. They also got it in a very simple way. The father of insurance mathematics, the Swedish applied mathematician Harald Cramér also got the point. And, more than two decades ago, practitioners such as Mark Spitznagel and myself build our entire business careers around it. (I personally get it right in words and when I trade and decisions, and detect when ergodicity is violated, but I never explicitly got the overall mathematical structure –ergodicity is actually discussed in Fooled by Randomness). Spitznagel and I even started an entire business to help investors eliminate uncle points so they can get the returns of the market. While I retired to do some flaneuring, Mark continued at his Universa relentlessly (and successfully, while all others have failed). Mark and I have been frustrated by economists who, not getting ergodicity, keep saying that worrying about the tails is “irrational”. Now there is a skin in the game problem in the blindness to the point. The idea I just presented is very, very simple. But how come nobody for 250 years got it? Skin in the game, skin in the game.

It looks like you need a lot of intelligence to figure probabilistic things out when you don’t have skin in the game. There are things one can only get if one has some risk on the line: what I said above is, in retrospect, obvious. But to figure it out for an overeducated nonpractitioner is hard. Unless one is a genius, that is have the clarity of mind to see through the mud, or have such a profound command of probability theory to see through the nonsense. Now, certifiably, Murray Gell-Mann is a genius (and, likely, Peters). Gell-Mann is a famed physicist, with Nobel, and discovered the subatomic particles he himself called quarks. Peters said that when he presented the idea to him, “he got it instantly”. Claude Shannon, Ed Thorp, Kelly and Cramér are, no doubt, geniuses –I can vouch for this unmistakable clarity of mind combined with depth of thinking that juts out when in conversation with Thorp. These people could get it without skin in the game. But economists, psychologists and decision-theorists have no genius (unless one counts the polymath Herb Simon who did some psychology on the side) and odds are will never have one. Adding people without fundamental insights does not sum up to insight; looking for clarity in these fields is like looking for aesthetic in the attic of a highly disorganized electrician. By Steve Blumenthal, CMG August 18, 2017 “Anything that has happened economically, has happened over and over again.” – Ray Dalio, founder, Bridgewater Associates, in Bloomberg interview My thinking is impatient and mostly critical as I sift through research each week. I’m sure my “get to the point” personality frustrates my co-workers and I’m sure at times my beautiful wife. It’s a personality flaw, I know; but hey, I’m just not sure any amount of therapy can help. As I sift through research, my head clicks doesn’t matter, doesn’t matter… matters! Last week I wrote about Camp Kotok. There were some important “matters” moments. For example, there was an interesting moment when Bloomberg’s Mike McKee fired hard questions at the panel of economists and former Fed insiders. Stress test very bright thinkers on stage with their peers and you get to watch their body language as you listen to their answers. Further, you get to watch the movements and facial expressions of others in the room. The panelists debated what the Fed will do next. The most important takeaway from camp was confirmation of my view that the Fed, at the highest level, is heavily reliant on, if not married to, a limited equation called the Phillips Curve. The Fed’s goals are to keep employment strong and inflation in check. The Phillips Curve is a single-equation empirical model, named after William Phillips, describing a historical inverse relationship between rates of unemployment and corresponding rates of inflation that result within an economy. The Phillips Curve assumes that high levels of employment will pressure wages, increase incomes, increase spending and drive inflation higher. And that is true in the short-term debt (or business cycles) we move through over time, but is it always true? In my view, the answer is no. I argued they need to consider where we are in terms of both the short-term and the long-term debt cycle. A retired senior Fed economist said to me, “Until someone comes up with a better model, it’s the best we’ve got.” At this moment in time, they are looking at the wrong thing. “Matters!” Put “how the Fed will likely react” in the matters category. Put the Phillips Curve in the matters category simply because it is what the Fed is focused on and not because it is the right metric and put, as I mentioned last week, the understanding of short-term and long-term debt cycles and where we are within those cycles in the matters most category. Bottom line: We sit at the end of a long-term debt cycle. One very few of us have ever seen before yet one that has happened many times over hundreds of years. The data exists. The Phillips Curve doesn’t see it. I wrote last week, “… the Fed is Focused on the Obvious and the Unimportant.” That is important for us to know. But then, what should the central bankers and you and I be focused on? Let’s take a look at that today and see if we can gain a better understanding. Meeting Bloomberg’s chief global economist Mike McKee at Camp Kotok was a real treat for me. If you have listened to Bloomberg radio over the years, you’ll know him as Tom Keene’s co-host. So how will the next few years play out? What does it mean in terms of the returns you are likely to receive? In the matters category, I believe this is what you and I need to know most. Following are my abbreviated notes from a recent Keene-McKee-Ray Dalio video interview to better understand how the economic machine works and how Bridgewater uses this understanding to invest their clients’ money. ---

So there are three equilibriums we have longer term:

And there is an equilibrium that keeps working itself through this system and monetary and fiscal policy are the tools we use as we work through short-term and long-term debt cycles. Tom Keene asks, “…we’ve enjoyed the last seven years. Where are we now within that equilibrium?” Dalio answered, The United States is in the mid-point of its short-term debt cycle so as a result central banks are talking about whether we should tighten or not. That’s what central banks do in the middle of the short-term cycle and we are near the end of a long-term debt cycle.

Tom Keene asks, “Within the framework of your economic machine, do you presume a jump condition (a jump up in rates) as central banks come out of this or can they manage it with smooth glide paths?” Ray answered, I don’t believe they can raise rates faster than is discounted in the curve. In other words, the rate at which it is discounted to rise which is built into the interest rate curve (the curve is the different yields you get for short-term Treasury Bills to long-term Treasury Bonds). This is built into all asset prices. So if you raise rates much more than is discounted in the curve, I think that is going to cause asset prices to go down. Because all things being equal, all assets sell at the present value of discounted cash flow. All assets are subject to this so if you raise rates faster than what is discounted in the curve, all things being equal, it will produce a downward pressure on all asset prices. And that’s a dangerous situation because the capacity of the central banks to ease has never been less in our lifetimes. So we have a very limited ability of central banks to be effective in easing monetary policy. Mike McKee asks, “What does a central bank do when you are at the end of a long-term debt cycle? When the Fed is at the zero bound (meaning a Fed Funds rate yielding 0%)?” Ray believes the pressure on the central banks will be on easing monetary policy (lowering rates) vs. tightening (raising rates). Ray said, “We are in an asymmetrical world where the risks of raising rates is far greater than lowering rates (this is due to where we sit in the long-term debt cycle including emerging market U.S. dollar denominated debt, commodity producing dollar denominated debts, Japan, Europe and China debts relative to GDP or their collective income).” Meaning if you raise rates, it affects the dollar and it affects foreign dollar dominated debt. So the risks on the downside are totally different than the risks on the upside. Ray suggests that the next big Fed move will be to ease and provide more QE. McKee asks, “Do you think QE works anymore?” Ray said, “It will work a lot less than it did last time. Just like each time it worked a lot less.” He’s saying we can’t have a big rate rise because of the amount of debt, because of what it will do to the dollar, because of the disinflation it will cause and we will have a downturn. And the downturn should be particularly concerning because we don’t have the same return potential with asset prices richly priced, so each series of QE cannot provide the same bump. You reach a point where QE is simply pushing on a string. You get nothing. McKee asked if we are there yet. Ray responded, “No, we are not there yet, but we are close. Some countries are there. Europe is there. What are you going to buy in a negative interest rate world? Japan is there. The effectiveness of monetary policy then comes through the currency (SB here: currency devaluation makes your goods cheaper to buy than my goods).” (SB here: QE creates money out of thin air and central banks use that money to buy assets. That money buys bonds from you and you then have money in your account to put to work. What will you then buy? Which country might you choose to invest?) Ray said, “If you look at us (the U.S.), we have very high rates in comparison to those in Europe and Japan. So it comes through the currency. If you can’t have interest rate moves (like in Europe) it comes through the currency.” Countries need to get their currencies lower to compete and drive growth. Can you see the mess that debt gets us into and the challenges reached at the end of long-term debt cycles?) I’m going to conclude my notes from the Bloomberg interview with this last comment from Ray: If you can’t have interest rate moves, you’ve got to have currency moves. And that’s the environment we are in. OK, my friend, I believe the Fed should be studying history. As I mentioned last week, they do talk with the likes of Bridgewater but it stops short of the top. I believe the Fed should be looking at what happens at periods in time when debt had reached, like today, ridiculous debt-to-GDP levels. That’s the road map. That’s the seminal issue. There are other important issues, of course, but I believe this one matters most. What I gained from my time at Camp Kotok was that the Fed is not reviewing history. They are not considering the dynamics of were we are in the long-term debt cycle. They are wed to the Phillips Curve. “Matters!”

How we reset the debt via a combination of monetary policy and fiscal policy will dictate a beautiful or ugly outcome. Risks are high because asset prices are significantly overvalued. Participate yes but have processes in place that protect. I believe the U.S. looks most favorable relative to the rest of the world and we will likely see more QE. I believe the Phillips Curve and the Fed’s desire to normalize rates (to put them in a better position to deal with the next cycle) will prove to be a mistake. As Ray said, “The risks are asymmetric.” The current rate hike period will be halted and more QE will follow. What happens between now and then? Don’t know. I suspect a shock followed by more global QE. The current state favors a stronger dollar and a strong U.S. equity market especially if there is a sovereign debt crisis in Europe. So yep… there’s that. Participate and protect and tighten your seat belt. Likely to be bumpy. Grab a coffee. There was a great piece from GMO titled, “The S&P 500: Just Say No.” It highlights how GMO comes to their 7-Year Real Asset Return Forecast. One that is currently predicting a -4.20% annualized real return over the coming seven years. As in a loss of nearly 4% per year. If true, expect every $100,000 of your wealth to equal $70,945 seven years from now. Ultimately, valuations do matter. So yep… that too. GMO has posted its forecast for many years. It is updated monthly. The accuracy rate has been excellent. Meaning the correlation to what they predicted to what returns turned out to be is very high. Not a guarantee, but put it too on your matters list. You can follow it here. You’ll find a few interesting charts. Thanks for reading. I hope you find this information helpful for you and your work with your clients. Have a great weekend. by Mark Spitznagel

The Mises Institute 14 August, 2017 Every further new high in the price of Bitcoin brings ever more claims that it is destined to become the preeminent safe haven investment of the modern age — the new gold. But there’s no getting around the fact that Bitcoin is essentially a speculative investment in a new technology, specifically the blockchain. Think of the blockchain, very basically, as layers of independent electronic security that encapsulate a cryptocurrency and keep it frozen in time and space — like layers of amber around a fly. This is what makes a cryptocurrency “crypto.” That’s not to say that the price of Bitcoin cannot make further (and further…) new highs. After all, that is what speculative bubbles do (until they don’t). Bitcoin and each new initial coin offering (ICO) should be thought of as software infrastructure innovation tools, not competing currencies. It’s the amber that determines their value, not the flies. Cryptocurrencies are a very significant value-added technological innovation that calls directly into question the government monopoly over money. This insurrection against government-manipulated fiat money will only grow more pronounced as cryptocurrencies catch on as transactional fiduciary media; at that point, who will need government money? The blockchain, though still in its infancy, is a really big deal. While governments can’t control cryptocurrencies directly, why shouldn’t we expect cryptocurrencies to face the same fate as what started happening to numbered Swiss bank accounts (whose secrecy remain legally enforced by Swiss law)? All local governments had to do was make it illegal to hide, and thus force law-abiding citizens to become criminals if they fail to disclose such accounts. We should expect similar anti-money laundering hygiene and taxation among the cryptocurrencies. The more electronic security layers inherent in a cryptocurrency’s perceived value, the more vulnerable its price is to such an eventual decree. Bitcoins should be regarded as assets, or really equities, not as currencies. They are each little business plans — each perceived to create future value. They are not stores-of-value, but rather volatile expectations on the future success of these business plans. But most ICOs probably don’t have viable business plans; they are truly castles in the sky, relying only on momentum effects among the growing herd of crypto-investors. (The Securities and Exchange Commission is correct in looking at them as equities.) Thus, we should expect their current value to be derived by the same razor-thin equity risk premiums and bubbly growth expectations that we see throughout markets today. And we should expect that value to suffer the same fate as occurs at the end of every speculative bubble. If you wanted to create your own private country with your own currency, no matter how safe you were from outside invaders, you’d be wise to start with some pre-existing store-of-value, such as a foreign currency, gold, or land. Otherwise, why would anyone trade for your new currency? Arbitrarily assigning a store-of-value component to a cryptocurrency, no matter how secure it is, is trying to do the same thing (except much easier than starting a new country). And somehow it’s been working. Moreover, as competing cryptocurrencies are created, whether for specific applications (such as automating contracts, for instance), these ICOs seem to have the effect of driving up all cryptocurrencies. Clearly, there is the potential for additional cryptocurrencies to bolster the transactional value of each other—perhaps even adding to the fungibility of all cryptocurrencies. But as various cryptocurrencies start competing with each other, they will not be additive in value. The technology, like new innovations, can, in fact, create some value from thin air. But not so any underlying store-of-value component in the cryptocurrencies. As a new cryptocurrency is assigned units of a store-of-value, those units must, by necessity, leave other stores-of-value, whether gold or another cryptocurrency. New depositories of value must siphon off the existing depositories of value. On a global scale, it is very much a zero sum game. Or, as we might say, we can improve the layers of amber, but we can’t create more flies. This competition, both in the technology and the underlying store-of-value, must, by definition, constrain each specific cryptocurrency’s price appreciation. Put simply, cryptocurrencies have an enormous scarcity problem. The constraints on any one cryptocurrency’s supply are an enormous improvement over the lack of any constraint whatsoever on governments when it comes to printing currencies. However, unlike physical assets such as gold and silver that have unique physical attributes endowing them with monetary importance for millennia, the problem is that there is no barrier to entry for cryptocurrencies; as each new competing cryptocurrency finds success, it dilutes or inflates the universe of the others. The store-of-value component of cryptocurrencies — which is, at a bare-minimum, a fundamental requirement for safe haven status — is a minuscule part of its value and appreciation. After all, stores of value are just that: stable and reliable holding places of value. They do not create new value, but are finite in supply and are merely intended to hold value that has already been created through savings and productive investment. To miss this point is to perpetuate the very same fallacy that global central banks blindly follow today. You simply cannot create money, or capital, from thin air (whether it be credit or a new cool cryptocurrency). Rather, it represents resources that have been created and saved for future consumption. There is simply no way around this fundamental truth. Viewing cryptocurrencies as having safe haven status opens investors to layering more risk on their portfolios. Holding Bitcoins and other cryptocurrencies likely constitutes a bigger bet on the same central bank-driven bubble that some hope to protect themselves against. The great irony is that both the libertarian supporters of cryptocurrencies and the interventionist supporters of central bank-manipulated fiat money both fall for this very same fallacy. Cryptocurrencies are a very important development, and an enormous step in the direction toward the decentralization of monetary power. This has enormously positive potential, and I am a big cheerleader for their success. But caveat emptor—thinking that we are magically creating new stores-of-value and thus a new safe haven is a profound mistake. Mark Spitznagel is Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Universa Investments. Spitznagel is the author of The Dao of Capital, and was the Senior Economic Advisor to U.S. Senator Rand Paul. by Nassim N. Taleb, Daniel G. Goldstein, and Mark W. Spitznagel

Harvard Business Review October 2009 We don’t live in the world for which conventional risk-management textbooks prepare us. No forecasting model predicted the impact of the current economic crisis, and its consequences continue to take establishment economists and business academics by surprise. Moreover, as we all know, the crisis has been compounded by the banks’ so-called risk-management models, which increased their exposure to risk instead of limiting it and rendered the global economic system more fragile than ever. Low-probability, high-impact events that are almost impossible to forecast—we call them Black Swan events—are increasingly dominating the environment. Because of the internet and globalization, the world has become a complex system, made up of a tangled web of relationships and other interdependent factors. Complexity not only increases the incidence of Black Swan events but also makes forecasting even ordinary events impossible. All we can predict is that companies that ignore Black Swan events will go under. Instead of trying to anticipate low-probability, high-impact events, we should reduce our vulnerability to them. Risk management, we believe, should be about lessening the impact of what we don’t understand—not a futile attempt to develop sophisticated techniques and stories that perpetuate our illusions of being able to understand and predict the social and economic environment. To change the way we think about risk, we must avoid making six mistakes. 1. We think we can manage risk by predicting extreme events. This is the worst error we make, for a couple of reasons. One, we have an abysmal record of predicting Black Swan events. Two, by focusing our attention on a few extreme scenarios, we neglect other possibilities. In the process, we become more vulnerable. It’s more effective to focus on the consequences—that is, to evaluate the possible impact of extreme events. Realizing this, energy companies have finally shifted from predicting when accidents in nuclear plants might happen to preparing for the eventualities. In the same way, try to gauge how your company will be affected, compared with competitors, by dramatic changes in the environment. Will a small but unexpected fall in demand or supply affect your company a great deal? If so, it won’t be able to withstand sharp drops in orders, sudden rises in inventory, and so on. In our private lives, we sometimes act in ways that allow us to absorb the impact of Black Swan events. We don’t try to calculate the odds that events will occur; we only worry about whether we can handle the consequences if they do. In addition, we readily buy insurance for health care, cars, houses, and so on. Does anyone buy a house and then check the cost of insuring it? You make your decision after taking into account the insurance costs. Yet in business we treat insurance as though it’s an option. It isn’t; companies must be prepared to tackle consequences and buy insurance to hedge their risks. 2. We are convinced that studying the past will help us manage risk. Risk managers mistakenly use hindsight as foresight. Alas, our research shows that past events don’t bear any relation to future shocks. World War I, the attacks of September 11, 2001—major events like those didn’t have predecessors. The same is true of price changes. Until the late 1980s, the worst decline in stock prices in a single day had been around 10%. Yet prices tumbled by 23% on October 19, 1987. Why then would anyone have expected a meltdown after that to be only as little as 23%? History fools many. You often hear risk managers—particularly those employed in the financial services industry—use the excuse “This is unprecedented.” They assume that if they try hard enough, they can find precedents for anything and predict everything. But Black Swan events don’t have precedents. In addition, today’s world doesn’t resemble the past; both interdependencies and nonlinearities have increased. Some policies have no effect for much of the time and then cause a large reaction. People don’t take into account the types of randomness inherent in many economic variables. There are two kinds, with socioeconomic randomness being less structured and tractable than the randomness you encounter in statistics textbooks and casinos. It causes winner-take-all effects that have severe consequences. Less than 0.25% of all the companies listed in the world represent around half the market capitalization, less than 0.2% of books account for approximately half their sales, less than 0.1% of drugs generate a little more than half the pharmaceutical industry’s sales—and less than 0.1% of risky events will cause at least half your losses. Because of socioeconomic randomness, there’s no such thing as a “typical” failure or a “typical” success. There are typical heights and weights, but there’s no such thing as a typical victory or catastrophe. We have to predict both an event and its magnitude, which is tough because impacts aren’t typical in complex systems. For instance, when we studied the pharmaceuticals industry, we found that most sales forecasts don’t correlate with new drug sales. Even when companies had predicted success, they underestimated drugs’ sales by 22 times! Predicting major changes is almost impossible. 3. We don’t listen to advice about what we shouldn’t do. Recommendations of the “don’t” kind are usually more robust than “dos.” For instance, telling someone not to smoke outweighs any other health-related advice you can provide. “The harmful effects of smoking are roughly equivalent to the combined good ones of every medical intervention developed since World War II. Getting rid of smoking provides more benefit than being able to cure people of every possible type of cancer,” points out genetics researcher Druin Burch in Taking the Medicine. In the same vein, had banks in the U.S. heeded the advice not to accumulate large exposures to low-probability, high-impact events, they wouldn’t be nearly insolvent today, although they would have made lower profits in the past. Psychologists distinguish between acts of commission and those of omission. Although their impact is the same in economic terms—a dollar not lost is a dollar earned—risk managers don’t treat them equally. They place a greater emphasis on earning profits than they do on avoiding losses. However, a company can be successful by preventing losses while its rivals go bust—and it can then take market share from them. In chess, grand masters focus on avoiding errors; rookies try to win. Similarly, risk managers don’t like not to invest and thereby conserve value. But consider where you would be today if your investment portfolio had remained intact over the past two years, when everyone else’s fell by 40%. Not losing almost half your retirement is undoubtedly a victory. Positive advice is the province of the charlatan. The business sections in bookstores are full of success stories; there are far fewer tomes about failure. Such disparagement of negative advice makes companies treat risk management as distinct from profit making and as an afterthought. Instead, corporations should integrate risk-management activities into profit centers and treat them as profit-generating activities, particularly if the companies are susceptible to Black Swan events. 4. We assume that risk can be measured by standard deviation. Standard deviation—used extensively in finance as a measure of investment risk—shouldn’t be used in risk management. The standard deviation corresponds to the square root of average squared variations—not average variations. The use of squares and square roots makes the measure complicated. It only means that, in a world of tame randomness, around two-thirds of changes should fall within certain limits (the –1 and +1 standard deviations) and that variations in excess of seven standard deviations are practically impossible. However, this is inapplicable in real life, where movements can exceed 10, 20, or sometimes even 30 standard deviations. Risk managers should avoid using methods and measures connected to standard deviation, such as regression models, R-squares, and betas. Standard deviation is poorly understood. Even quantitative analysts don’t seem to get their heads around the concept. In experiments we conducted in 2007, we gave a group of quants information about the average absolute movement of a stock (the mean absolute deviation), and they promptly confused it with the standard deviation when asked to perform some computations. When experts are confused, it’s unlikely that other people will get it right. In any case, anyone looking for a single number to represent risk is inviting disaster. 5. We don’t appreciate that what’s mathematically equivalent isn’t psychologically so. In 1965, physicist Richard Feynman wrote in The Character of Physical Lawthat two mathematically equivalent formulations can be unequal in the sense that they present themselves to the human mind in different ways. Similarly, our research shows that the way a risk is framed influences people’s understanding of it. If you tell investors that, on average, they will lose all their money only every 30 years, they are more likely to invest than if you tell them they have a 3.3% chance of losing a certain amount each year. The same is true of airplane rides. We asked participants in an experiment: “You are on vacation in a foreign country and are considering flying the national airline to see a special island you have always wondered about. Safety statistics in this country show that if you flew this airline once a year there would be one crash every 1,000 years on average. If you don’t take the trip, it is extremely unlikely you’ll revisit this part of the world again. Would you take the flight?” All the respondents said they would. We then changed the second sentence so it read: “Safety statistics show that, on average, one in 1,000 flights on this airline has crashed.” Only 70% of the sample said they would take the flight. In both cases, the chance of a crash is 1 in 1,000; the latter formulation simply sounds more risky. Providing a best-case scenario usually increases the appetite for risk. Always look for the different ways in which risk can be presented to ensure that you aren’t being taken in by the framing or the math. 6. We are taught that efficiency and maximizing shareholder value don’t tolerate redundancy. Most executives don’t realize that optimization makes companies vulnerable to changes in the environment. Biological systems cope with change; Mother Nature is the best risk manager of all. That’s partly because she loves redundancy. Evolution has given us spare parts—we have two lungs and two kidneys, for instance—that allow us to survive. In companies, redundancy consists of apparent inefficiency: idle capacities, unused parts, and money that isn’t put to work. The opposite is leverage, which we are taught is good. It isn’t; debt makes companies—and the economic system—fragile. If you are highly leveraged, you could go under if your company misses a sales forecast, interest rates change, or other risks crop up. If you aren’t carrying debt on your books, you can cope better with changes. Overspecialization hampers companies’ evolution. David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage recommended that for optimal efficiency, one country should specialize in making wine, another in manufacturing clothes, and so on. Arguments like this ignore unexpected changes. What will happen if the price of wine collapses? In the 1800s many cultures in Arizona and New Mexico vanished because they depended on a few crops that couldn’t survive changes in the environment.… One of the myths about capitalism is that it is about incentives. It is also about disincentives. No one should have a piece of the upside without a share of the downside. However, the very nature of compensation adds to risk. If you give someone a bonus without clawback provisions, he or she will have an incentive to hide risk by engaging in transactions that have a high probability of generating small profits and a small probability of blowups. Executives can thus collect bonuses for several years. If blowups eventually take place, the managers may have to apologize but won’t have to return past bonuses. This applies to corporations, too. That’s why many CEOs become rich while shareholders stay poor. Society and shareholders should have the legal power to get back the bonuses of those who fail us. That would make the world a better place. Moreover, we shouldn’t offer bonuses to those who manage risky establishments such as nuclear plants and banks. The chances are that they will cut corners in order to maximize profits. Society gives its greatest risk-management task to the military, but soldiers don’t get bonuses. Remember that the biggest risk lies within us: We overestimate our abilities and underestimate what can go wrong. The ancients considered hubris the greatest defect, and the gods punished it mercilessly. Look at the number of heroes who faced fatal retribution for their hubris: Achilles and Agamemnon died as a price of their arrogance; Xerxes failed because of his conceit when he attacked Greece; and many generals throughout history have died for not recognizing their limits. Any corporation that doesn’t recognize its Achilles’ heel is fated to die because of it. --- Nassim N. Taleb is the Distinguished Professor of Risk Engineering at New York University’s Polytechnic Institute and a principal of Universa Investments, a firm in Santa Monica, California. He is the author of several books, including The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (Random House, 2007). Daniel G. Goldstein is an assistant professor of marketing at London Business School and a principal research scientist at Yahoo. Mark W. Spitznagel is a principal of Universa Investments. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed