|

by Danielle Dimartino-Booth

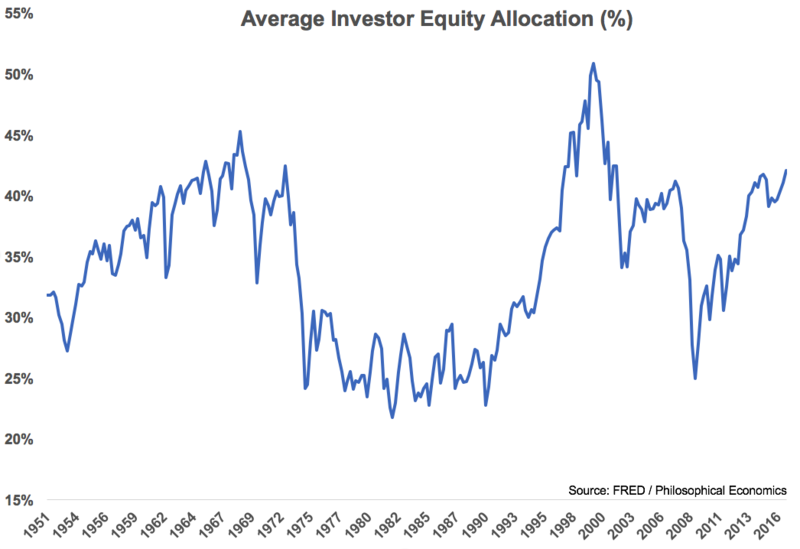

July 26, 2017 5:12 am, April 18, 1906. A foreshock rocked the San Francisco Bay area followed 20 seconds later by one of the strongest earthquakes in recorded history. The quake, which lasted a full minute, was felt from southern Oregon to south of Los Angeles and inland as far as central Nevada. In the aftermath, the shock to the financial system was equally violent. Precious gold stores were withdrawn from the world’s major money centers to address the City by the Bay’s devastation. What followed was a run on liquidity that culminated in a recession beginning in June 1907. A decline in the U.S. stock market, combined with tight credit markets across Europe and a Bank of England in a tightening mode, set the stage. Against the backdrop of rising income inequality spawned by the Gilded Age, distrust towards the financial community had burgeoned among working class Americans. Into this precarious fray, a scandal erupted centered on one F. Augustus Heinze’s machinations to corner the stock of United Copper Company. The collapse of Heinze’s scheme exposed an incestuous and corrupt circle of bank, brokerage house and trust company directors to a wary public. What started as an orderly movement of deposits from bank to bank devolved into a full scale run on Friday, October 18, 1907. Revelations that Charles Barney, president of Knickerbocker Trust Company, the third largest trust in New York, had also been ensnared in Heinze’s scheme sufficed to ignite systemic risk. Absent a backstop for depositors, J.P. Morgan famously organized a bailout to prevent the collapse of the financial system. Chief among his advisers on aid-worthy solvent institutions was Benjamin Strong, who would become the first president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Nearly 100 years later to the day, on May 2, 2006, California-based subprime lender Ameriquest announced it would lay off 3,800 of its nationwide workforce and close all 229 of its retail branches. There’s no need to rehash what followed. It remains fresh in many of our minds. Still, as we few skeptics who were on the inside of the Federal Reserve at the time can attest, that watershed moment also shattered the image of the false era that had sowed so many doubts, dubbed simply, The Great Moderation. It is said that the Great Inflation gave way to the Great Moderation, so named due to the decrease in macroeconomic volatility the U.S. economy enjoyed from the 1980s through the onset of that third ‘Great,’ The Great Financial Crisis. This from a 2004 speech given by none other than Ben Bernanke, who presided over this magnificent epoch: “My view is that improvements in monetary policy, though certainly not the only factor, have probably been an important source of the Great Moderation.” How very modestly moderate of him. To be precise, standard deviation gauges the volatility of a given data set by measuring how far from its long-run trend it swings; the higher the number, the more volatile, and vice versa. According to Bernanke’s own research, the standard deviation of GDP fell by half and that of inflation by two-thirds over this period of supreme calm. In late 2013, Fed historians published a retrospective on The Great Moderation, which concluded as such: “Only the future will tell for certain whether the Great Moderation is gone or is set to continue after the harrowing interruption of recent years. As long as the changes in the structure of the economy and good policy explained at least part of the Great Moderation, and have not been undone, then we should expect to return at least partially to the Great Moderation. And perhaps with financial stability being a more prominent objective and better integrated with monetary policy, financial shocks such as those seen over the past several years will be less common and have less severe impacts. If the Great Moderation is still with us, its reemergence in the aftermath of the Great Recession will be as welcome now as its first emergence was following the turbulence of the Great Inflation. As for its causes, economists may disagree on the relative importance of different factors, but there is little question that ‘good policy’ played a role. The Great Moderation set a high standard for today’s policymakers to strive toward.” Strive they have, and succeeded spectacularly, by their set standards. It matters little. Insert the observable phenomenon with anything that pertains to the macroeconomy and the financial markets, and you will see that volatility is all but extinct. The volatility on stocks, as gauged by the VIX index, hit its lowest intraday level on record July 25 of this year. As for how much stocks are jostling about on any given day, that’s sunk to the lowest in 50 years. Treasury market volatility is at a…record low. A lack of volatility in the price of oil is peeving those manning the commodities pits. Even go-go assets are dormant. The risk premium, or extra compensation you receive to own junk bonds, is negative. Negative! But this non-news spreads far beyond asset prices and presumably hits policymakers’ sweetest spot. According to some excellent reporting by the Wall Street Journal’s Justin Lahart, “Over the past three years, the standard deviation of the annualized change in U.S. gross domestic product…is just 1.5 percentage points, or about as low as it has ever been. It is a trend that is being matched elsewhere, with global GDP exhibiting the lowest volatility in history.” Lahart goes on to add that job growth and corporate profits also seem stunned into submission. And then he goes for the jugular: “In the years since the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve and other central banks have acted like overprotective parents of a toddler, rushing in whenever the economy looks as if it might stumble. That risk-averse behavior has extended to businesses, making them unwilling to take chances.” The WSJ goes on to report that at no time in at least 30 years has not one of the three major stock indexes in the U.S., Asia and Europe avoided a five percent decline in a calendar year…until what we’ve seen thus far in 2017, that is. Is it any wonder the ranks of those who would profit from stocks declining have fallen to a four-year low? Why bother in such a perfect world? In other words, we’ve never had it this good, or perhaps this bad. In that case, this must be The Greater Moderation. And by the looks of things, it’s gone global. It’s no secret that the Bank of England, Bank of Japan and European Central Bank have been aggressively flooding their respective economies and in turn, the global financial system, with liquidity in some form of quantitative easing. If there is one lesson to be learned from The Great Moderation, it is that liquidity acts as a shock absorber. In a less liquid world, the crash in oil prices would have resulted in a bankruptcy bloodbath. In a less liquid world, the bursting of the housing bubble would have led to millions of foreclosed homes clearing at fire sale prices. In a less liquid world, highly leveraged firms would have been rendered insolvent and incapable of covering their interest costs. In short, a less liquid world would be smaller, for a time. But when the time came to allow nature to take its course, central bankers could not bear the pain, nor muster the discipline, to allow creative destruction to cull the weakest from the herd. Their policies have forced us to pay a dear price to maintain a population of inefficient operators. The Economist recently featured a report on “corporate zombies”, firms that in a normal world would not walk among the living. Defining a ‘zombie’ as a company whose earnings before tax do not cover its interest expenses, the Bank for International Settlements placed 14 developed countries under the microscope. On this basis, the average proportion of zombies among publicly listed companies grew from less than six percent in 2007 to 10.5 percent in 2015. So we have one-in-ten firms effectively sucking the life out of the world economy’s ability to regenerate itself. There is no such thing as a productivity conundrum against a backdrop of such widespread misallocation of capital and labor. There is no mystery cloaking the breakdown in new business formation. And there is no enigma, much less any reason to assign armies of economists to investigate, shrouding the new abnormality we’ve come to know as a low growth world. There is simply no room for an economy to excel when its growth potential is choked off by an overabundance of liquidity that is perverting incentives. What is left behind is a yield drought, one that has left the whole of the world painfully parched for income and returns and yet too weary to conduct fundamental risk analysis. You have Greece returning to the debt markets after a three-year exile and investors falling over themselves to get their hands on the junk-rated bonds; the offering was more than two times oversubscribed. Argentina preceded this feat, selling the first-of-its kind, junk-rated 100-year-maturity, or ‘century’ bond; it was 3.5 times oversubscribed. Closer to home, Moody’s reports that lending to corporations has gone off the rails. Two-in-three loans offer no safeguards to lenders in the event a borrower hits financial distress; that’s up from 27 percent in 2015. Meanwhile, the kingpins of private equity have assumed such great powers, they’ve built in provisions that prohibit secondary market buyers of loans from assembling to make demands on their firms’ managements. Corporate lending standards in Europe are looser yet. What are investors, big and small, to do? Apparently, sit back and do as they’re told to do: Buy in, but passively, and let the machines do their bidding. For institutions, add in alternative investments at hefty fees and throw in leverage to assist in elevating returns. In late June, the recently retired Robert Rodriguez, a 33-year veteran of the markets, sat down for a lengthy interview with Advisor Perspectives (linked here). Among his many accolades, Rodriguez carries the unique distinction of being crowned Morningstar Manager of the Year for his outstanding management of both equity and bond funds. He likens the current era to that of the nine years ended 1951, a period during which the Fed and Treasury held interest rates at artificially low levels to finance World War II. His main concern today is that price discovery has been so distorted by the Fed that the stage is set for a ‘perfect storm.’ His personal allocation to equities is at the lowest level since 1971. The combination of meteorological forces to bring on said storm, you ask? It may well be an act of God, an earthquake. It could just as easily be a geopolitical tremor the system cannot absorb; it’s easy enough to name a handful of potential aggressors. Or history may simply rhyme with the unrelenting shock waves that catalyzed the subprime mortgage crisis, coupled per chance with a plain vanilla recession. We may simply and slowly wake to the realization that the assumptions we’ve used to delude ourselves into buying the most expensive credit markets in the history of mankind are built on so much quicksand. The point is panics do not randomly come to pass; they must be shocked into existence as was the case in advance of 1907 and 2007. One of Rodriguez’s observations struck a raw nerve for yours truly, who prides herself on being a reformed central banker: “The last great central banker that we had in the last 110 years other than Volcker was J.P. Morgan. The difference is, when Morgan tried to contain the 1907 crisis, he wasn’t using zeros and ones of imaginary computer money; he was using his own capital.” It is only fair and true to honor history and add that Morgan’s efforts rescued depositors. Income inequality in the years that followed 1907 declined before resuming its ascent to its prior peak, reached at the climax of the Roaring Twenties. The Fed’s intrusions since 2007, built on the false premise of a fanciful wealth effect concocted using models that have no place in the real world, have accomplished the opposite. Income inequality has not only grown in the aftermath of The Great Financial Crisis and throughout The Greater Moderation; it has long since smashed through its former 1927 record and kept rising. The Fed’s actions have not saved the little guy; they’ve skewered him. “The world in which we live has an increasing number of feedback loops, causing events to be the cause of more events (say, people buy a book because other people bought it), thus generating snowballs and arbitrary and unpredictable planet-wide winner-take-all effects.” – Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan By John Mauldin

Mauldin Economics July 22, 2017 “What do you do?” is a common question Americans ask people they have just met. Some people outside the US consider this rude – as if our jobs define who we are. Not true, of course, but we still feel obliged to answer the question. My work involves so many different things that it isn’t easy to describe. My usual quick answer is that I’m a writer. My readers might say instead: “He tells people what could go wrong.” I like to think of myself as an optimist, and I do often write about my generally optimistic view of the future, but that optimism doesn’t often extend to the performance of governments and central banks. Frankly, we all face economic and financial risks, and we all need to prepare for them. Knowing the risks is the first step toward preparing. Exactly 10 years ago we were months way from a world-shaking financial crisis. By late 2006 we had an inverted yield curve steep and persistent enough to be a high-probability indicator of recession 12 months later. So in late 2006 I was writing about the probability that we would have a recession in 2007. I was also writing about the heavy leverage in the banking system, the ridiculous level of high-yield offerings, the terms and potential turmoil in the bond and banking markets, and the crisis brewing in the subprime market. I wish I had had the money then that a few friends did to massively leverage a short position on the subprime market. I estimated at that time that the losses would be $400 billion at a minimum, whereupon a whole lot of readers and fellow analysts told me I was just way too bearish. Turned out the losses topped well over $2 trillion and triggered the financial crisis and Great Recession. Conditions in the financial markets needed only a spark from the subprime crisis to start a firestorm all over the world. Plenty of things were waiting to go wrong, and it seemed like they all did at the same time. Governments and central bankers scrambled hard to quench the inferno. Looking back, I wish they had done some things differently, but in the heat of battle – a battle these particular people had never faced before, with more going wrong every day – it was hard to be philosophically pure. (Sidebar: I think the Fed's true mistakes were QE2, QE3, and missing their chance to start raising rates in 2013. By then, they had time to more carefully consider those decisions.) We don’t have an inverted yield curve now, so the only truly reliable predictor of recessions in the US is not sounding that warning. But when the central bank artificially holds down short-term rates, it is difficult if not almost impossible for the yield curve to invert. We have effectively suppressed that warning signal, but I am laser focused on factors that could readily trigger a global recession, resulting in another global financial crisis. All is not well in the markets. Yes, we see stock benchmarks pushing to new highs and bond yields at record lows. Inflation benchmarks are stable. Unemployment is low and going lower. GDP growth is slow, but it’s still growth. All that says we shouldn’t worry. Perversely, the signs that we shouldn’t worry are also reasons why we should. This is a classic Minsky teaching moment: Stability breeds instability. I know the bullish arguments for why we can’t have another crisis. Banks are better capitalized now. Regulators are watching more intently. Bondholders are on notice not to expect more bailouts. All that’s true. On the other hand, today’s global megabanks are much larger than their 2008 versions were, and they are more interconnected. Most Americans – the 80% I’ve called the Unprotected – are still licking their wounds from the last battle. Many are in worse shape now than in 2008. Our crisis-fighting reserves are low. European banks are still highly leveraged. The shadow banking system in China has grown to scary proportions. Globalization has proceeded apace since 2008, and the world is even more interconnected now. Problems in faraway markets can quickly become problems close to home. And that’s without a global trade war. I am concerned that another major crisis will ensue by the end of 2018 – though it is possible that a salutary combination of events, aided by complacency, could let us muddle through for another few years. But there is another recession in our future (there is always another recession), and it’s going to be at least as bad as the last one was, in terms of the global pain it causes. The recovery is going to take much longer than the current one has, because our massive debt build-up is a huge drag on growth. I hope I’m wrong. But I would rather write these words now and risk eating them in my 2020 year-end letter than leave you unwarned and unprepared. Because I’m traveling this week, this letter will be just a few appetizers –black swan hot wings, black swan meatballs in orange sauce, teriyaki swan skewers, and the like – to whet your appetite and help you anticipate what’s coming. Seriously speaking, could the three scenarios we discuss below turn out be fateful black swans? Yes. But remember this: A harmless white swan can look black in the right lighting conditions. Sometimes that’s all it takes to start a panic. Black Swan #1: Yellen Overshoots It is increasingly evident, at least to me, that the US economy is not taking off like the rocket some predicted after the election. President Trump and the Republicans haven’t been able to pass any of the fiscal stimulus measures we hoped to see. Banks and energy companies are getting some regulatory relief, and that helps; but it’s a far cry from the sweeping healthcare reform, tax cuts, and infrastructure spending we were promised. Though serious, major tax reform could postpone a US recession to well beyond 2020, what we are going to get instead is tinkering around the edges. On the bright side, unemployment has fallen further, and discouraged workers are re-entering the labor force. But consumer spending is still weak, so people may be less confident than the sentiment surveys suggest. Inflation has perked up in certain segments like healthcare and housing, but otherwise it’s still low to nonexistent. Is this, by any stretch of the imagination, the kind of economy in which the Federal Reserve should be tightening monetary policy? No – yet the Fed is doing so, partly because they waited too long to end QE and to begin reducing their balance sheet. FOMC members know they are behind the curve, and they want to pay lip service to doing something before their terms end. Moreover, Janet Yellen, Stanley Fischer, and the other FOMC members are religiously devoted to the Phillips curve. That theory says unemployment this low will create wage-inflation pressure. That no one can see this pressure mounting seems not to matter: It exists in theory and therefore must be countered. The attitude among central bankers, who are basically all Keynesians, is that messy reality should not impinge on elegant theory. You just have to glance at the math to recognize the brilliance of the Phillips curve! It was Winston Churchill who said, “However beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results.” Fact is, the lack of wage growth among the bottom 70–80% of workers (the Unprotected class) constitutes a real weaknesses in the US economy. If you are a service worker, competition for your job has kept wages down. The black-swan risk here is that the Fed will tighten too much, too soon. We know from recent FOMC minutes that some members have turned hawkish in part because they wanted to offset expected fiscal stimulus from the incoming administration. That stimulus has not been forthcoming, but the FOMC is still acting as if it will be. What happens when the Fed raises interest rates in the early, uncertain stages of a recession instead of lowering them? I’m not sure we have any historical examples to review. Logic suggests the Fed will extinguish any inflation pressure that exists and push the economy in the opposite direction instead, into outright deflation. Deflation in an economy as debt-burdened as ours is could be catastrophic. We would have to repay debt with cash that is gaining purchasing power instead of losing it to inflation. Americans have not seen this happen since the 1930s. It wasn’t fun then, and it would be even less fun now. Worse, I doubt Trump’s FOMC appointees will make a difference. Trump appears to be far more interested in reducing the Fed’s regulatory role than he is in tweaking its monetary policies. I have no confidence that Yellen’s successor, whoever that turns out to be, will know what needs to be done or be able to do it fast enough. Let me make an uncomfortable prediction: I think the Trump Fed – and since Trump will appoint at least six members of the FOMC in the coming year, it will be his Fed – will take us back down the path of massive quantitative easing and perhaps even to negative rates if we enter a recession. The urge to “do something,” or at least be seen as trying to do something, is just going to be too strong. Black Swan #2: ECB Runs Out of Bullets Last week, news reports said that the Greek government is preparing to issue new bonds for the first time in three years. “Issue bonds” is a polite way of saying “borrow more money,” something many bond investors think Greece is not yet ready to do. Their opinions matter less than ECB chief Mario Draghi’s. Draghi is working hard to buy every kind of European paper except that of Greece. Adding Greece to the ECB bond purchases program would certainly help. Relative to the size of the Eurozone economy, Draghi’s stimulus has been far more aggressive then the Fed’s QE. It has pushed both deeper, with negative interest rates, and wider, by including corporate bonds. If you are a major corporation in the Eurozone and the ECB hasn’t loaned you any money or bought your bonds yet, just wait. Small businesses, on the other hand, are being starved. Such interventions rarely end well, but admittedly this one is faring better than most. Europe’s economy is recovering, at least on the surface, as the various populist movements and bank crises fade from view. But are these threats gone or just glossed over? The Brexit negotiations could also throw a wrench in the works. Despite recent predictions by ECB watchers and the euro’s huge move up against the dollar on Friday, Anatole Kaletsky at Gavekal thinks Draghi is still far from reversing course. He expects that the first tightening steps won’t happen until 2018 and anticipates continued bond buying (at a slower pace) and near-zero rates for a long time after. But he also sees risk. Anatole explained in a recent report: Firstly, Fed tapering occurred at a time when Europe and Japan were gearing up to expand monetary stimulus. But when the ECB tapers there won’t be another major central bank preparing a massive balance sheet expansion. It could still turn out, therefore, that the post-crisis recovery in economic activity and the appreciation of asset values was dependent on ever-larger doses of global monetary stimulus. If so, the prophets of doom were only wrong in that they overstated the importance of the Fed’s balance sheet, compared with the balance sheets of the ECB and Bank of Japan. This is a genuine risk, and an analytical prediction about the future on which reasonable people can differ, unlike the factual observations above regarding the revealed behavior of the ECB, the Franco-German rapprochement and the historical experience of Fed tapering. Secondly, it is likely that the euro will rise further against the US dollar if the ECB begins to taper and exits negative interest rates. A stronger euro will at some point become an obstacle to further gains in European equity indexes, which are dominated by export stocks. Anatole makes an important point. The US’s tapering and now tightening coincided with the ECB’s and BOJ’s both opening their spigots. That meant worldwide liquidity was still ample. I don’t see the Fed returning that favor. Draghi and later Kuroda will have to normalize without a Fed backstop – and that may not work so well. Black Swan #3: Chinese Debt Meltdown China is by all appearances unstoppable. GDP growth has slowed down to 6.9%, according to official numbers. The numbers are likely inflated, but the boom is still underway. Reasonable estimates from knowledgeable observers still have China growing at 4–5%, which, given China’s size, is rather remarkable. The problem lies in the debt fueling the growth. Ambrose Evans-Pritchard reported some shocking numbers in his July 17 Telegraph column. A report from the People’s Bank of China showed off-balance-sheet lending far higher than previously thought and accelerating quickly. (Interestingly, the Chinese have made all of this quite public. And President Xi has taken control of publicizing it.) The huge increase last year probably reflects efforts to jump-start growth following the 2015 downturn. Banks poured fuel on the fire, because letting it go out would have been even worse. But they can’t stoke that blaze indefinitely. President Xi Jinping has been trying to dial back credit growth in the state-owned banks for some time; but in the shadow banks that Xi doesn’t control, credit is growing at an astoundingly high rate, far offsetting any minor cutbacks that Xi has made. Here are a few more juicy quotes from Ambrose: President Xi Jinping called for a hard-headed campaign to curb systemic risk and to flush out “zombie companies”, warning over the weekend that financial stability was a matter of urgent national security. It is the first time that a Chinese leader has chaired the National Finance Work Conference – held every five years to thrash out long-term plans – and is a sign of rising concern as debt reaches 280pc of GDP. In a move that will send shivers up the spines of local party officials, he said they will be held accountable for the rest of their lives for debts that go wrong. Any failure to identify and tackle risks will be deemed “malfeasance”. Ambrose then quotes Patrick Chovanec of Silvercrest Asset Management: “The banks have been selling products saying it isn’t our risk. Investors have been buying them saying it’s not our risk either. They all think the government will save everything. So what the markets are pricing is what they think is political risk, not economic risk,” he said. A market in which “they all think the government will save everything” is generally not one you want to own – but China has been an exception. It won’t remain one forever. The collapse, when it comes, could be earthshaking. Chinese growth has been fueled by a near doubling of both GDP and debt over the last nine years. One reason why so many people are complacent about China is that they truly believe that “this time is different” applies to Chinese debt. Maybe in 10 years I will look back and say that it really was different, but I don’t think so. As is often the case with China, China’s current circumstances are without a true equal in the history of the world. And if Xi is really serious about slowing the pace of growth (another form of tightening by a major world economy), that move would just add to overall global risk. It is very possible that any of these black swans could trigger a recession in the US. And let’s be clear: The next US recession will be part of a major global recession and will result in massive new government debt build-up. It will not end well. by Mohamed A. El-Erian

21 July 2017 Bloomberg View Over the past few months, government bond yields have fallen, the dollar has weakened and financials have underperformed, yet the major stock indexes are at or very near record highs, as persistently supportive liquidity conditions have more than compensated for policy and growth disappointments. By boosting returns and repressing volatility, ample liquidity is a gift for investors. It makes the investment journey pleasing, comfortable and lengthy. But it is not a destination. With the exception of buoyant stock market indexes, it is hard to find many financial markets that have managed to retain their post-U.S. election mood. Specifically:

Much of this reflects the process of markets repricing to lower expectations for U.S. growth and for Federal Reserve policy tightening compared to the rest of the world, and especially relative to Europe and the European Central Bank. The main reason for this is reduced hopes for a rapid economic policy breakthrough powered by the implementation of tax reform and infrastructure programs. Despite Republican majorities in both chambers, Congress has struggled to come together on major legislation, most visibly health care (an issue that dominated the party’s narrative during the campaign). This has delayed pro-growth economic bills, while making their prospects more uncertain. With Fed monetary measures already stretched, there has been little policy offset to a soft patch in indicators of household and corporate economic activity. Yet none of this seems to have been reflected in the major stock indexes. All three -- the Dow Jones, Nasdaq and S&P -- registered more record highs this week. In the process, the leadership of the market has returned to tech and other disruptors, after a brief but intense post-election romance with financials and industrials deemed to be the largest beneficiary of Trumponomics. The markets’ overall sense of "goldilocks" -- not too hot, not too cold -- explains much of the gap between buoyant stock indexes and lagging economic and policy fundamentals. Growth may be low, but the markets perceive it as relatively stable. The Trump administration has not followed through on protectionist measures that would threaten a global trade war. Concerns about disruptive European politics, to the extent they even registered in stock markets, have been alleviated by President Emmanuel Macron’s victory in France. Interest rates continue to be low throughout the advanced world, with markets also marking down their expectations of Fed tightening in the last few weeks. Two systemically important central banks, the ECB and the Bank of Japan, continue to provide a lot of liquidity, and on a predictable monthly schedule; and, as signaled on Thursday by ECB President Mario Draghi, they seem in no rush to taper, despite the improvement in economic conditions. Moreover, with corporate balance sheets flush with cash, valuations are also influenced by understandable expectations of more dividends, stock buybacks, and mergers and acquisitions. Liquidity, especially when ample and predictable, can fuel markets and condition investor behavior in a supportive manner for quite a while. But when judged against the objective of durable long-term gains, it is best seen as part of the investment journey. The destination, however, doesn't depend on liquidity alone. Economic and corporate fundamentals play a much larger role. So far, equity investors have experienced an unusually long and fulfilling journey -- one that, absent a major accident, could last a little longer. What remains more elusive, however, is confidence that this will end up at an enjoyable destination. But the most reassuring factor for traders and investors remains very loose financial conditions. by Mark Spitznagel

The Mises Institute 14 July, 2017 There seems to be no shortage today of investors and pundits criticizing the market interventions of the world’s central banks. Monetary stimulus in the form of artificially low interest rates and bloated central bank balance sheets ($18.5 trillion, to be exact), the argument goes, have created another dangerous financial bubble (evidenced by ubiquitously bubbly stock market valuation ratios) that ultimately threatens the financial system yet again. The author shares wholeheartedly in this criticism. The ethical problem is, where were these voices when this all started, with Greenspan in the 1990s and, more specifically, with Bernanke in 2008? The central bank critics today who were not critics of — and in most cases were even sympathetic to — the great bailouts and stimulus that started almost a decade ago have reserved their criticisms only for those interventions that appear to hurt their interests, as opposed to those that have helped them. After all, no one would disagree that bailouts and monetary stimulus got us out of the last financial crisis, but they also certainly got us to where we are today, vulnerable to another even bigger one. We are so concerned about our friend the strung-out junkie, though we paid little mind when they were but a casual user. It is so easy to care when problems become obvious and critical, so hard when they are subtler and nascent. Artificial stimulus in an economy is the same: it is easily ignored as a problem in its infancy, but it always develops into a huge problem. Economies and markets are structurally altered and distorted by such stimulus, such that it cannot be removed without breaking those new structures. It must rather be ever increased, though even this will only delay an inevitable collapse. It is just too easy in today’s investing environment, and even necessary for most participants, to sympathize with and even exploit central bank interventions. Doing otherwise creates an opportunity cost in one’s career and investments. But doing so puts one in the position of enabler to the economic system’s self-destructive dependence on artificial stimulus. One cannot be a part-time classical liberal, criticizing central planning only when it runs contrary to one’s interests. Indeed, this is the very problem of Socialism: there are winners and losers; the winners are in the here and now — the seen; the losers are in the future — the unseen. The winners don't complain, and the losers can‘t until it is too late. But as the future becomes the here and now, the unseen becomes the seen, those who now think they are anticipating a problem and its cause, yet supported that same cause when they stood to benefit, must be seen for what they are: fellow travelers in the central planning ideology that grips today’s financial markets. They are too late. by R. Christopher Whalen

Institutional Risk Analyst July 6, 2017 News last week that European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi was considering an end to the ECB’s extraordinary purchases of securities quickly let some air out of the Great Rotation into EU stocks. Sure the euro surged against a weakening dollar, but Europe’s mountain of bad debt remains unresolved -- even after the election of Emmanuel Macron to the French presidency. Yet hope springs eternal in some quarters after Draghi’s claim of a successful “reflation.” “All the signs now point to a strengthening and broadening recovery in the euro area,” Draghi told the ECB’s annual conference. “Deflationary forces have been replaced by reflationary ones,” the former head of the Bank of Italy declared. Draghi’s bull call on inflation provides optimism for relief on excessive levels of bad debt, albeit in a context where the EU’s rules on resolving dead banks remain entirely subjective. The July 4 approval of the latest state-supported rescue for Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena (Montepaschi) illustrates the deflationary challenges still facing Europe. As part of the overhaul, Reuters reports, Montepaschi “will transfer 26.1 billion euros to a privately funded special vehicle on market terms, with the operation partially funded by Italian bank rescue fund Atlante II.” The bank will receive 5 billion euros in new public equity funds for its third bailout in a decade. Two weeks before the EU decision on rescuing Montepaschi, the Italian government supported the sale of two profoundly insolvent Italian banks. The assets of Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca were sold to Intesa SanPaolo Group at an estimated cost to the government of 10 billion euros, marking Italy’s latest breech of the EU’s rules on state support for failing financial institutions. Like Montepaschi, where retail investors were heavily subsidized, the Intesa SanPaolo transaction avoids imposing losses on senior debt and depositors, but wipes out the equity and junior debt. This outcome reflects political as well as financial constraints in Italy, but shows how far there is to go in the process of resolving bad banks in Europe. Of note, Italy is being given control over the remaining “bad bank” to wind down as the assets and deposits are conveyed to Intesa SanPaolo. This permits a bailout of senior unsecured creditors. So Italy gets what it wants – continued circumvention of EU bailout rules. If a bank disappears, notes a well-placed EU observer, “state aid rules do not apply." Compare the sale of these two insolvent Italian banks with the resolution in early June of Banco Popular Espanol, which became the first EU bank to be resolved by the EU’s Single Resolution Board (SRB). Banco Popular had a third of total assets in bad loans and real estate owned, double the 15% average for all banks in Spain. (In the US, by comparison, non-performing loans plus real estate owned equaled less than 1% of total assets for all banks at the end of Q1 2017.) “The resolution of Banco Popular, under which it was acquired by Banco Santander S.A., is consistent with the EU’s Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive (BRRD),” Moody’s notes, “which restricts the use of public funds to rescue failing banks. The route followed by the EU authorities in the case of Banco Popular contrasts with the approach taken elsewhere to other ailing banks, notably in the case of the troubled Italian lender Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena S.p.A.” The state bailout of Montepaschi, like the sale of the two smaller banks to Intesa SanPaolo, reflects political realities in Italy. “Montepaschi’s liability structure includes large volumes of bonds purchased by retail investors before the [Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive] introduction,” Moody’s continues. “Retail investors also accounted for around 40% of Banco Popular’s share capital and also held an undisclosed share of the bank’s Tier 2 instruments.” Well-advised institutional investors fled Italian banks years ago, partly because they could not trust official disclosure. So the Rome government countenanced the sale of “deposits” to retail investors by Montepaschi and other Italian zombie banks. The process of selling the deposits and good assets of the two Italian zombie banks to Intesa SanPaolo, while retaining the toxic waste in a “bad bank”, represents the true cost of this latest example of moral hazard in Europe. Draghi deserves considerable credit for the worsening situation at Montepaschi, starting with his tenure at the Bank of Italy. When the bank merged with Antonveneta, a troubled bank it bought from Spain’s Santander, Montepaschi’s troubles accelerated. Italy's third-biggest lender, received a 4 billion euro state bailout in 2012. The negative political consequences for the current government in Rome of the latest Montepaschi bailout are still unfolding, but Draghi and his fellow technocrats are the true authors of this mess. More, EU banks still face levels of bad debts that not only indicate insolvency, but under the EU’s often ignored fiscal rules, suggest a haircut for senior debt and depositors without state aid. As with the EU today, American officials in the late 1970s and 1980s bent the rules regarding bank disclosure to enable most of the larger, internationally active US banks to avoid a painful debt restructuring. The Latin debt crisis, trouble in the oil patch, and the S&L debacle pushed some of America’s largest banks to the edge of bankruptcy, starting a process of deregulation that is still little understood by investors and analysts. The Federal Reserve Board under Chairman Paul Volcker and other regulators allowed large banks to engage in off-balance sheet financial transactions that concealed tens of billions in loan exposures. This loosening of prudential standards regarding the treatment of off-balance sheet securities deals eventually led to the 2008 financial collapse. Three decades later, when concealed structured investment vehicles came back to issuers like Citigroup (NYSE:C), the results were disastrous. Today, officials in Europe led by ECB chief Mario Draghi are playing a similar game, pretending that bad public and private debt on the books of EU banks and investment houses, and held by individuals, is somehow money good. As with the US in the 1980s, the stark reality inside the EU banking system is being concealed under a heavy dose of technocratic obfuscation. Mountains of public debt in Europe also indicate proponents of the bullish EU equity trade may be a tad exuberant. Europe just dodged a bullet in Greece, where a last-minute deal with the International Monetary Fund allowed the member nations to kick the can down the road until next year. With debt at 200% of GDP, Greece is crippled economically and requires debt reduction in order to attract new investment. Over the past few months, investors have driven yields on Greek debt to the lowest level in years. To that point, investor optimism on the EU is predicated on an eventual debt bailout for Greece. Yet investors won't see any details on a long awaited Greek debt restructuring plan before the German elections later this year. The EU trade, as it were, depends an awful lot on what happens to Angela Merkel’s coalition this September. Economic reality is slowly leading the EU down the road to the assumption of bad debt of weaker states by the stronger members of the federation led by Germany. EU economic commissioner Pierre Moscovici has called for “debt reduction” in Greece, a proposal that is met with a lukewarm response by Germans. But will Merkel ultimately go along? "In the long run, in a completely integrated euro zone, we would talk about a ‘communitization’ of new debt, but we're not going to start with that," Moscovici told reporters last week. The necessary condition for the bull case on the EU is that the Germans must eventually embrace a federated structure for Europe, this as part of a gradual approach being advanced by leaders such as Macron in France and Moscovici in Brussels. Joint and several responsibility for all EU debts is the cost of unity. Such a scenario faces significant political and practical obstacles, most notably in Germany but also in France, where Macron must somehow convince his citizens to embrace German style economic behavior. A gradualist plan for a European federation seems unworkable so long as member states are able to borrow against Europe’s collective credit without toeing the line on fiscal reforms – as in the case of Italy and its troubled banks. “The euro crisis resulted from the fallacy that a monetary union would evolve into a political union,” writes Yanis Varoufakis, a former finance minister of Greece. “Today, a new gradualist fallacy threatens Europe: the belief that a federation-lite will evolve into a viable democratic federation.” |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed