|

As market collapsed, hedge-fund firm Universa Investments gained roughly 20% on Monday By Juliet Chung The Wall Street Journal August 28, 2015 The recent market rout caught some star Wall Street traders by surprise. But not a hedge-fund firm affiliated with “The Black Swan” author Nassim Nicholas Taleb, which gained more than $1 billion on a strategy that seeks to profit from extreme events in financial markets. Universa Investments LP was up roughly 20% on Monday, according to a person familiar with the matter, a day when the Dow Jones Industrial Average collapsed more than 1,000 points in its largest intraday point decline. The blue-chip index finished down 588 points on the day. The fund’s returns for the year climbed to roughly 20% through earlier this week, this person said. Universa holds positions designed to protect about $6 billion in client assets, according to people familiar with the firm. “This is just the beginning,” said Universa founder Mark Spitznagel, referring to the market volatility this week. His longtime collaborator, Mr. Taleb, who advises Universa, is a professor at New York University and is known for his pessimistic forecasts on the global economy. “The markets are overvalued to the tune of 50%, and I’ve been saying that for some time,” said Mr. Spitznagel, who has spent the past several years warning of a coming correction he viewed as inevitable given the easy-money policies by central banks around the world. Miami-based Universa and other “black swan” hedge funds that seek to reap big rewards from sharp market downturns emerged as winners amid the world-wide volatility of the past week, according to investors. These funds “so far this month have been very strong,” said Gregg Hymowitz, founder of New York-based hedge-fund investor EnTrust Capital Inc., who has invested in several such funds since 2011. “If your house burns down, you want to have some protection.” The funds’ nickname refers to the long-held belief that all swans are white, proved false when European explorers found black swans in Australia. In finance, a black-swan event refers to something extreme and highly unexpected, like the financial crisis. Mr. Taleb popularized the term in his best-selling 2007 book. Some funds racked up double-digit percentage gains in the past week, largely on Monday. Capstone Investment Advisors LLC is up 52%, or nearly $100 million, for August through Wednesday, nearly all of it coming from gains last Friday through Tuesday, according to a person familiar with the matter. Black Eyrar, a fund of London-based 36 South Capital Advisors LLP, was up in the double-digit percentages for August through Friday, according to a person familiar with the fund. A similar fund at Boaz Weinstein’s Saba Capital Management LP was up 14% for August through Friday, according to an investor, bringing its returns for the year to 1%. “We wait for times like these,” said Jerry Haworth, 36 South’s co-founder and chief investment officer. Black-swan funds came into vogue in the years after the financial crisis, as concerns mounted about another recession, a potential increase in interest rates by the Federal Reserve and a European crisis, investors said. Their strategies aren’t an easy sell to prospective investors because the funds tend to lose money steadily for several years before making a profit. Some critics said they can be too expensive and lead clients to pull out at the wrong time. Universa, which was founded in 2007, first attracted attention for its outsize gains in 2008, racking up more than 100% profits for many of its clients. It profited in 2010, and in 2011 it notched gains of about 10% to 30% for clients. In other years, it has lost small amounts of money. The firm focuses on finding cheap, shorter-dated options on the S&P 500 and other instruments it expects to rise in value amid a notable downturn. During the past week, the value of put options that Universa bought over the past one to two months jumped, said people familiar with the matter. A put option confers the right, but not the obligation, to sell a security at a specified price, usually within a limited period. Mr. Spitznagel, a former Chicago Board of Trade pit trader who worked at the proprietary-trading desk of Morgan Stanley, described Monday’s fall as a “blip” compared with what could still happen, though he said it was unusual because of the speed of the decline and its timing so close to market highs. “The stock market has climbed to where it has over the six-plus years because of central banks, but people forget how crazy and unsustainable that is,” Mr. Spitznagel said. Unlike a typical hedge fund, clients don’t hand over their entire account to Universa’s Black Swan Protection Protocol. Instead, they designate a certain pool of assets, a notional value, that they seek to hedge, or protect from extreme losses. Typically, Universa hedges against clients’ U.S. stockholdings. For example, a client that has a $100 million account with Universa would pay the firm a flat annual fee of 1.5% on that amount, or $1.5 million. The client would transfer to Universa typically less than 10% to fund the purchase of hedges for its account. Universa managed roughly $300 million in assets at the end of last year, according to a regulatory filing. by Nassim Taleb

Absolute Return Magazine Aughust 11, 2015 Nassim Nicholas Taleb, is Distinguished Scientific Adviser at Universa Investments, author of “The Black Swan,” and Distinguished Professor of Risk Engineering at New York University Polytechnic Institute. Uncertainty should not bother you. We may not be able to forecast when a bridge will break, but we can identify which ones are faulty and poorly built. We can assess vulnerability. And today the financial bridges across the world are very vulnerable. Politicians prescribe ever larger doses of pain killer in the form of financial bailouts, which consists in curing debt with debt, like curing an addiction with an addiction, that is to say it is not a cure. This cycle will end, like it always does, spectacularly. When it comes to investing in this environment, my colleague Mark Spitznagel articulated it well: investors are left with a simple choice between chasing stocks that have an increasing chance of a crash or missing out on continued policy effects in the short term. Incorporating a tail hedge minimizes the risk in the tail, allowing investors to remain invested over time without risking ruin. Spitznagel put together a video explaining the point here. To be robust, one must construct a portfolio as an engineer would a bridge and ask what your managers expect to lose should the market fall by 10%. Then ask them again what they’d expect to lose in the down 20% scenario. If that second number is more than two times more painful emotionally than the first, your portfolio is fragile. To fix the problem, add components to your portfolio that make the portfolio stronger in a crash, like actively managed put options. You will be able to build stronger, better bridges, with better returns, that will last for the long term. By clipping the tail, you can own more risk, the good type of risk: upside with limited downside. And rather than helplessly watching your bridge collapse, you can be opportunistic in a crash, and take the pieces from others at bargain prices to increase the size of yours. Weekly Market Comment

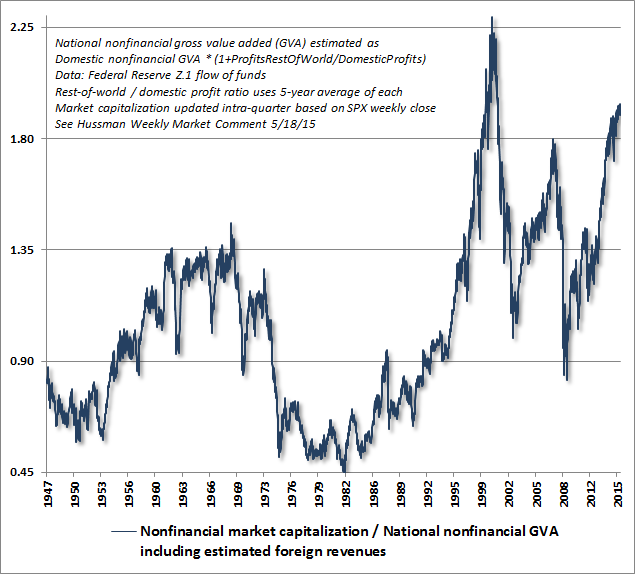

John P. Hussman, Ph.D. August 3, 2015 From our perspective, the fundamental reason for economic stagnation and growing income disparity is straightforward: Our current set of economic policies supports and encourages a low level equilibrium by encouraging debt-financed consumption and discouraging saving and productive investment. We permit an insular group of professors and bankers to fling trillions of dollars about like Frisbees in the simplistic, misguided, and repeatedly destructive attempt to buy prosperity by maximally distorting the financial markets. We offer cheap capital and safety nets to too-big-to-fail banks by allowing them to speculate with the same balance sheets that we protect with deposit insurance. We pursue easy monetary fixes aimed at making people “feel” wealthier on paper, far beyond the fundamental value that has historically backed up that wealth. We view saving as dangerous and consumption as desirable, failing to recognize a basic accounting identity: there can only be a "savings glut" in countries that fail to stimulate investment. We leave central bankers in charge of our economic future because we're too timid to directly initiate or encourage productive investment through fiscal policy. When zero interest rates don't do the trick, we begin to imagine that maybe negative interest rates and penalties on saving might coerce people to spend now. Look around the world, and that same basic policy set is the hallmark of economic failure on every continent. --- Be careful here – deteriorating internals matter. The condition of market internals is precisely the same hinge that – in market cycles across history – has separated overvalued markets that continued to advance from overvalued markets that collapsed through a trap door. That’s not to say that stocks must collapse immediately; market peaks are a process, not an event. That’s also not to say that market internals could not improve, which wouldn’t relieve extreme valuations, but could very well defer their immediate consequences. We’ll take our evidence as it arrives, but at present, we view the condition of the equity market as precarious. As a guide to how we expect the current market cycle to be completed, the chart below presents the ratio of market capitalization/gross value added, which has the strongest correlation with actual subsequent S&P 500 10-year nominal total returns of any valuation ratio we’ve examined across history (including Shiller P/E, market capitalization/GDP, price/revenue, price/dividend, price/book, Tobin’s Q, price/trailing earnings, price/forward earnings, the Fed Model, and other variants). On reliable measures available since the late-1880’s, as well as estimates imputed from historical data, current valuations now easily exceed the 1907 peak, the 1929 peak, the 1937 peak, the 1973 peak, the 1987 peak, the 2007 peak, and indeed every market peak in history except 2000. Moreover, the valuation of the median stock on the basis of price/earnings and price/revenue ratios considerably exceeds the 2000 peak here – because the 2000 peak was more focused on large-capitalization stocks, particularly in the technology sector. Put simply, the recent market peak represents the second most overvalued point in history for the capitalization-weighted stock market, and the single most overvalued point in history for the broad market. August 04, 2015

Size matters. Just ask Roy Scheider. As incredulous as it may seem, I only recently sat myself down to watch that American scare-you-out-of-the-water staple Jaws for the first time. As a baby born in 1970, the movie at its debut in 1975 was hugely inappropriate for my always precocious, but nevertheless only five-year old self. And by the time this Texas girl and those Yankee cousins of mine were pondering breaking the movie rules during those long-ago summers in Madison, Connecticut, it was not Jaws but rather Brat Pack movies that tempted us. We started down our road of movie rebellion with St. Elmo's Fire, then caught up with a poor Molly Ringwald in Pretty in Pink and then really stretched our boundaries with Less than Zero - you get the picture. And so finally during this long, hot summer of 2015, a seemingly appropriate time with our country gripped from coast to coast with real-life shark hysteria, I watched Jaws for the first time and heard Roy Scheider as Chief Martin Brody utter those words, "You're gonna need a bigger boat." Prophetically, the reality might just be that the collective "we," and quite possibly sooner than we think, really will need a bigger boat. That is, as it pertains to the global debt markets, which have swollen past the $200 trillion mark this year rendering the great white featured in Jaws, which can be equated with past debt markets, as defenseless and small as a teensy, striped Nemo by comparison. The question for the ages will be whether size really does matter when it comes to the debt markets. It's been more than three years since Bridgewater Associates' Ray Dalio excited the investing world with the notion that the levered excesses that culminated in the financial crisis could be unwound in a "beautiful" way. A finely balanced combination of austerity, debt restructuring and money printing could provide the pathway to a gentle outcome to an egregious era. In Mr. Dalio's words, "When done in the right mix, it isn't dramatic. It doesn't produce too much deflation or too much depression. There is slow growth, but it is positive slow growth. At the same time, ration of debt-to-income go down. That's a beautiful deleveraging." I'll give him the slow growth part. Since exiting recession in the summer of 2009, the economy has expanded at a 2.1-percent rate. I know beauty is in the eye of the beholder but the wimpiest expansion in 70 years is something only a mother could feign admiration for. That not-so-pretty baby still requires the wearing of deeply tinted rose-colored glasses to maintain the allusion. As for the money printing, $11 trillion worldwide and counting certainly checks off another of Dalio's boxes. But refer to said growth extracted and consider the price tag and one does begin to wonder. As for debt restructuring, it's questionable how much has been accomplished. There's no doubt that some creditors, somewhere on the planet, have been left holding the proverbial bag -- think Cypriot depositors and (yet-to-be-determined) Energy Future Holdings' creditors. Still, the Fed's extraordinary measures in the wake of Lehman's collapse largely stunted the culmination of what was to be the great default cycle. Had that cycle been allowed to proceed unhampered, there would be much less in the way of overcapacity across a wide swath of industries. Instead, as a recent McKinsey report pointed out, and to the astonishment of those lulled into falsely believing that deleveraging is in the background quietly working 24/7 to right debt's ship, re-leveraging has emerged as the defeatist word of the day. Apparently, the only way to supply the seemingly endless need for more noxious cargo to fill the world's rotting debt hulk is by astoundingly creating more toxic debt. Since 2007, global debt has risen by $57 trillion, pushing the global debt-to-GDP ratio to 286 percent from its starting point of 269 percent. Of course, the Fed is not alone in its very liberal inking and priming of the presses. Central banks across the globe have been engaged in an increasingly high stakes race to descend into what is fast becoming a bottomless abyss in the hopes of spurring the lending they pray will jump start their respective economies. Perhaps it's time to consider the possibility that low interest rates are not the solution. Debt is a fickle witch. When left to its own devices, which it has been for nearly seven years with interest rates at the zero bound, it tends to get into trouble. Unchecked credit initially seeps, and eventually finds itself fracked, into the dark, dank nooks and crannies of the fixed income markets whose infrastructures and borrowers are ill-suited to handle the capacity. Consider the two flashiest badges of wealth in America - cars and homes. These two big-line items sales' trends used to move in lockstep -- that is until the powers that be at the FOMC opted to leave interest rates too low for too long. In Part I, aka the housing bubble, home sales outpaced car sales as credit forced its way onto the household balance sheets of those who could no more afford to buy a house than they could drive a Ferrari. True deleveraging of mortgage debt has indeed taken place since that bubble burst, mainly through the mechanism of some 10 million homes going into foreclosure. It's no secret that credit has resultantly struggled mightily to return to the mortgage space since. Today though, Part II of this saga features an opposite imbalance that's taken hold. Car sales have come unhinged from that of homes and are roaring ahead at full speed, up 76 percent since the recession ended six years ago, more than three times the pace of home sales over the same period. It's difficult to fathom how car sales are so strong. Disposable income, adjusted for inflation, is up a barely discernible 1.5 percent in the three years through 2014. Add the loosest car lending standards on record to the equation and you quickly square the circle. Little wonder that the issuance of securities backed by car loans is racing ahead of last year's pace. If sustained, this year will take out the 2006 record. At what cost? Maybe the record 16 percent of used car buyers taking out 73-84 month loans should answer that question. To be sure, car loans are but a drop in the $57 trillion debt bucket. The true overachievers, at the opposite end of the issuance spectrum, have been governments. The growth rate of government debt since 2007 has been 9.3 percent, a figure that explains the fact that global government debt is nearing $60 trillion, nearly double that of 2007. The plausibility of the summit to the peak of this mountain of debt is sound enough considering the task central bankers faced as the global financial system threatened to implode (thanks to their prior actions, mind you). In theory, government securities are as money good as you can get. Practice has yet to be attempted. The challenge when pondering $200 trillion of debt is that it's virtually impossible to pinpoint the next stressor. Those who follow the fixed income markets closely have their sights on the black box called Chinese local currency debt. A few basics on China and its anything-but-beautiful leverage. Since 2007 China's debt has quadrupled to $28 trillion, a journey that leaves its debt-to-GDP ratio at 282 percent, roughly double its 2007 starting point of 158 percent. For comparison purposes, that of Argentina is 33 percent (hard to borrow with no access to debt markets); the US is 233 percent while Japan's is 400 percent. If Chinese debt growth continues at its pace, it will rocket past the debt sound barrier (Japan) by 2018. As big as it is, China's debt markets have yet to withstand a rate-hiking cycle, hence investors' angst. My fear is of that always menacing great white swimming in ever smaller circles closer and closer to our shores. I worry about sanguine labels attached to untested markets. US high-grade bonds come to mind in that respect even as investors calmly but determinately exit junk bonds. Over the course of the past decade, the US corporate bond market has doubled to an $8.2 trillion market. A good portion of that growth has come from high yield bonds. But the magnificence has emanated from pristine issuers who have had unfettered access to the capital markets as starved-for-yield investors clamor to debt they deem to have a credit ratings close to that of Uncle Sam's. Again, labels are troublesome devils. Remember subprime AAA-rated mortgage-backed securities? We've grown desensitized to multi-billion issues from high grade companies. Most investors sleep peacefully with the knowledge that their portfolios are indemnified thanks to a credit rating agency's stamp of approval. Mom and pop investors in particular are vulnerable to a jolt: the portion of the bond market they own through perceived-to-be-safe mutual funds and ETFs has doubled over the past decade. Retail investors probably have little understanding of the required, intricate behind-the-scenes hopscotching being played out by huge mutual fund companies. This allows high yield redemptions to present a smooth, tranquil surface with little in the way of annoying ripples. That might have something to do with liquidity being portable between junk and high grade funds - moves made under the working assumption that the Fed will step in and assure markets that more cowbell will always be forthcoming rather than risk the slightest of dramas unfolding. Once the reassurance is acknowledged by the market, all can be righted in the ledgers. It's worked so far. But investors have yet to even consider selling their high grade holdings. It's unthinkable. It's hard to fathom that back in 1975 when I was a kindergartener, security markets' share of U.S. GDP was negligible. Forty years later, liquidity is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon. That is, until it's not. Nary are any of us far removed from a poor stricken soul who has suffered a fall from grace. In the debt markets, a "fallen angel" is a term assigned to a high grade issuer that descends to a junk-rated state. It could just as easily refer to any credit in the $200 trillion universe investors perceive as being risk-free. Should the need arise, will there be enough room on policymakers' boats to provide seating for every fallen angel? That is certainly the hope. But what if the real bubble IS the sheer size of the collective balance sheet? If that's the case, we really are gonna need a bigger boat. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed