|

by R. CHristopher Whalen

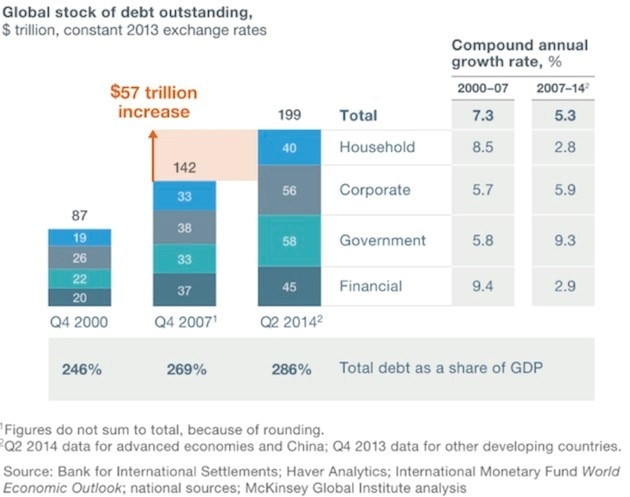

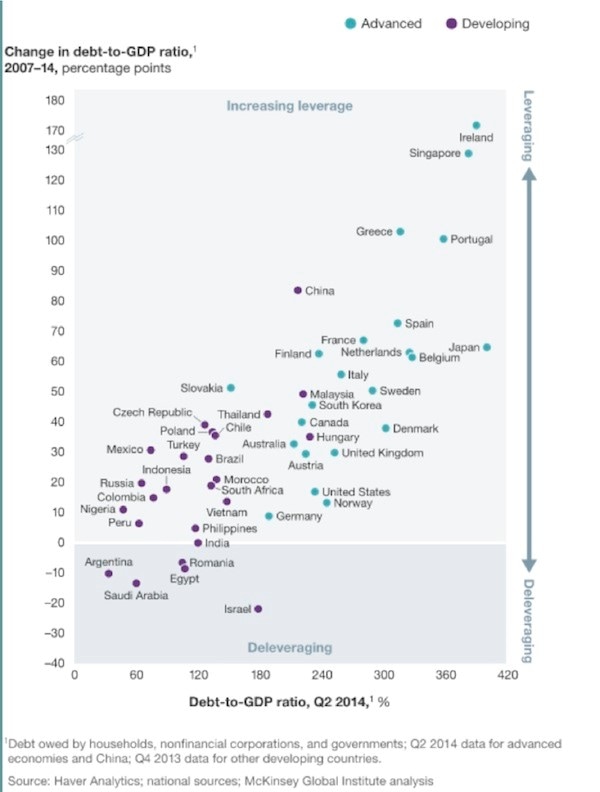

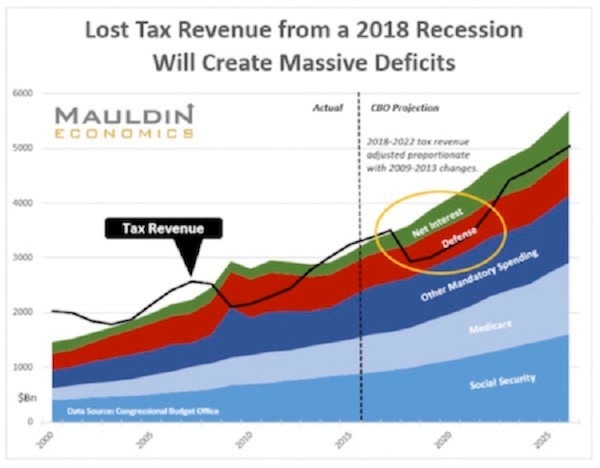

The Institutional Risk Analyst May 29, 2017 In the mid 2000s, just before the financial crisis began, US banks were reporting credit metrics for all asset classes in loan portfolios that were quite literally too good to be true. And they were. The cost of bad credit decisions was hidden, for a time, by rising asset prices. The same aggressive, low-rate environment used by the Fed to artificially stoke growth in the early 2000s has been repeated in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, only to a greater extreme. Today US banks report credit metrics in many loan categories that are not merely too good, but are entirely anomalous. Negative default rates, for example, are a red flag. A decade ago, the more aggressive lenders such as Wachovia, Countrywide and Washington Mutual were actually reporting negative net default rates, suggesting that extending credit had no cost – in large part because the value of the collateral behind the loans was rising in value. In those heady days of comfortable collective delusions, non-current rates for 1-4 family loans were below 1%, the lowest levels of delinquency since the early 1990s. This situation changed rather dramatically by 2007, when several large west-coast non-bank mortgage lenders collapsed. By the start of 2008, funding for banks, non-banks and even the GSEs was drying up and default rates were rising rapidly. The cost of credit reappeared. Net-charge off rates for 1-4 family loans in particular went from 0.06% early in 2005 to 1.5% by the end of 2008 and peaked at 2.5% by the end of 2009. Today the irrational exuberance of the Federal Open Market Committee has created huge asset price bubbles in sectors such as residential and commercial real estate. A combination of low rates, a dearth of home builders (down 40% from ~ 550k firms in 2008 to ~ 330k firms today) and even less construction & development (C&D) lending (down ~ 30-40%) has constrained the supply of homes. But low rates sent prices for existing homes soaring multiples of annual GDP growth – both for single-family and multifamily properties. Keep in mind that the folks on the Federal Reserve Board think that asset price inflation is helpful – thus the “wealth effect.” Specifically, the FOMC believes that manipulating risk preferences, credit spreads and therefore asset prices helps the economy to generate more income and employment. Many analysts have debunked the notion of a “wealth effect,” but the FOMC persists in this thinking even today. Mohamed E-Erian writing in Bloomberg has it right: “Forced to use the 'asset channel' as the main vehicle for pursuing its macroeconomic growth and inflation objectives – that is, boosting asset prices to make consumers feel wealthier and spend more, and also to increase corporate investments by fueling animal spirits – the Fed has ended up providing exceptional multiyear support to financial markets using an experimental array of unconventional tools and forward policy guidance. Indeed, most investors and traders are now conditioned to expect soothing words from central bankers – and, if needed, policy actions – the minute markets hit a rough patch, virtually regardless of the reason.” In an economic sense, the Federal Open Market Committee is the heart of the Administrative State. The use of the “asset channel” to pretend to boost economic activity is part of the larger delusion at the Fed known as “macro-prudential” policy. The macro-prudential worldview sees the Fed as an all knowing, all-seeing global managerial agency that can somehow balance goosing economic growth using asset bubbles with preventing the associated systemic risks. Note that regulating whole industries and constraining growth is, in fact, a key part of the Fed’s macropru model. Having maintained low interest rates and used trillions of dollars of bank reserves to fund open market purchases of Treasury bonds and agency mortgage paper, the FOMC now faces an asset market that has understated the cost of credit for over a decade. From 2001 through 2007, and then 2009 through today, the FOMC has boosted asset prices – but without a commensurate and necessary increase in income. The Fed has, to paraphrase El-Erian, decoupled prices from fundamentals and distorted asset allocation in markets and the economy. SO the question that concerns The IRA is when will the credit cycle turn and how much of the apparently benign credit picture we see today is a function of the Fed’s social engineering? If this latest round of Fed “ease” is more radical than that seen in the early 2000s, will we see an even sharper uptick in bank loan loss rates than we saw in 2007-2009? So how does this all end? In the short term, look for default rates on consumer exposures to continue rising. But in asset classes like commercial real estate, residential homes and C&D lending, we suspect that the party may continue, at least in statistical terms, through at least the end of the year. After that, however, we full expect to see loss rates and LGDs start to snap back to the middle of the proverbial distribution. As one well-placed bank CEO told The IRA over breakfast, “there are lots of sweaty palms” in the New York commercial real estate market. Read this little missive in The New York Times about the Park Lane Hotel to get a sense of the level of exuberance in the commercial real estate market in Gotham. Without a rather robust confirmation of asset prices with rising incomes, as El_Erian and many others have observed, current levels of assets prices are unlikely to be maintained. In the event, look for bank default and recovery rates to normalize, with a sharp increase in credit costs for lenders and bond investors alike. Trees do not grow to the sky, credit costs are never really negative, and last we looked, Fed chairs cannot fly through the air or spin straw into gold. But they can manipulate asset prices and cause other mischief that, we suspect, represents a net cost to consumers and investors alike. But this is hardly a novel state of affairs. In that regard, we appreciate your comments about our earlier missive, “Buy Britain, Sell Europe.” Many of you challenged our idea that Britain is an enduring nation state, while the EU is merely a bad idea whose sell by date has passed. To address these comments, we refer to one of our favorite reads of late, “Playing Catch Up,” by Wolfgang Streeck. The emeritus director of the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies in Cologne, Streeck writes regularly for the London Review of Books. He is ready to suspend democratic processes to support “willing governments” that advance German-style reforms, but Streeck has a cogent view of the European political economy: “Here, as so often in her long career, Merkel is anything but dogmatic, and certainly isn’t beholden to ordoliberal orthodoxy since what is at stake is Germany’s most precious historical achievement, secure access to foreign markets at a low and stable exchange rate. For several years now, Berlin has allowed the European Central Bank under Draghi and the European Commission under Juncker to invent ever new ways of circumventing the Maastricht treaties, from financing government deficits to subsidising ailing banks. None of this has done anything to resolve the fundamental structural problems of the Eurozone. What it has done is what it was intended to do: buy time, from election to election, for European governments to carry out neoliberal reforms, and for Germany to enjoy yet another year of prosperity.” Sound familiar? In the US as well as Europe, what passes for fiscal and monetary policy are merely a series of short-term expedients meant to get us from one day to the next. The nonsense of macro-prudential policy represents the apex of such thinking. As we look out to credit conditions in the US banking sector in 2H 2017 and beyond, the one sure bet is that the cost of credit will not remain suppressed forever. by John Mauldin Mauldin Economimcs May 22, 2017 The Great Reset We are coming to a period I call the Great Reset. As it hits, we will have to deal, one way or another, with the largest twin bubbles in the history of the world: global debt, especially government debt, and the even larger bubble of government promises. We are talking about debt and unfunded promises to the tune of multiple hundreds of trillions of dollars – vastly larger than global GDP. We are also going to have to restructure our economies and in particular how we approach employment because of the massive technological transformation that is taking place. But let’s keep the focus for now on global debt and government promises. All that debt cannot be repaid under current arrangements, nor can those promises ultimately be kept. There is simply not enough money and not enough growth, and these bubbles are continuing to grow. At some point, we’re going to have to deal with these issues and restructure everything. Now, people have been saying that for years. Remember Ross Perot and his charts in the early 1990s? We’ve all heard the doom and gloom predictions of the demise of civilization that will be brought on by our Social Security and/or healthcare and/or pension problems. And yet, these are real problems we must face. Facing them won’t be the end of the world, but it will mean we must forge a different social contract and make changes to taxes and the economy. That said, the day of reckoning is not here yet. We have time to adjust and prepare. But I believe that within the next 5–10 years we have to confront the ending of the debt and government promises supercycle that has been developing since the late 1930s. This is a global problem, but it will be felt most acutely in the developed world and China. The developing and frontier markets will be radically affected as well, but mostly by fallout from the impacts on the developed world. There has been no instance in history when too much debt didn’t eventually have to be dealt with. The even more massive bubble of government promises will have to be dealt with, too. We need some realistic way to decide how to meet those promises, or at least the portion of them that can be met. For the record, what I mean by government promises are pensions and healthcare benefits in all their myriad varieties. Governments everywhere guaranteed these benefits assuming that taxes would cover their immediate costs and future politicians would figure out the rest. Now the time is rapidly approaching when those “future politicians” are the ones we elect in the here and now. What Happened to Deleveraging? Typically, after a significant recession there is a deleveraging of society. That’s certainly what many expected in 2009. Individuals in some countries did in fact reduce their debts, but not governments and corporations, or most individuals outside the US. That the world is awash in debt is not exactly news. As of 2014, total global debt had risen to $199 trillion, growing some $57 trillion in just the previous seven years, about $8 trillion a year. The McKinsey Institute chart below shows 22 advanced and 25 developing countries that make up the bulk of the world economy. The chart illustrates how the debt is split among household, corporate, government, and financial sectors: The debt-to-GDP ratio increased in all advanced economies from 2007 through 2014, and the trend is continuing. Here’s a chart for the advanced and developing economies: Since that 2014 report was published, global debt rose by $17 trillion through 3Q 2016. In fact, in the first nine months of 2016 global debt rose $11 trillion! After averaging a little over $8 trillion from 2007 through 2014, global debt growth is now accelerating. Global debt-to-GDP is now 325%, though it varies sharply by region and country. More worrisome is that interest rates are slowly rising pretty much everywhere, so debt-servicing costs are rising, too. In the US, according to a note sent to me recently by my friend Terry Savage, Interest on the national debt is the third largest component of our annual Federal budget – after social programs and military spending. In the most recent fiscal year, we paid $240 billion in interest on the national debt. That was a relatively low cost, because the Fed has kept interest rates artificially low for years – as savers can attest. Now, with the Fed hiking rates, interest costs are set to soar. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that every percentage point hike in rates will cost $1.6 trillion over the next ten years! And that’s without adding to the debt itself every year, by running budget deficits. That 1% rate hike will take roughly an additional 3% of our current tax revenues every year. Governments must cover higher interest costs with additional taxes, lower spending, or an increase in the deficit (which means more total debt and even more interest rate cost). Of course, higher interest rates affect more than just government interest rates. Many of us have adjustable-rate mortgages and other loans with floating interest rates. It is not just the US that faces a serious debt problem. Global GDP is roughly $80 trillion. If interest rates were to rise just 1% on our global debt, an additional $2 trillion of that GDP would go to pay that debt increase, or about 1.5% of global GDP. As we have discussed many times, debt is a limiting factor on future growth. Debt is future consumption brought forward. Repaying that debt requires either reduced future consumption or some kind of debt liquidation – those are the only choices. Debt has additional consequences. I have highlighted research from my friends Lacy Hunt and Van Hoisington that correlates increased total debt with slower overall growth. The graph below from Hoisington Investment Management shows total debt as a percentage of GDP for the major developed countries. Note that Japan, with by far the highest debt-to-GDP ratio, is growing slower than Europe, which is growing slower than the US. China’s debt is rapidly overtaking the US’s debt, and at its current growth rate it will soon overtake Europe’s. The grand Chinese debt experiment will eventually reveal the true linkage between the size of debt and growth. Unfunded Liabilities A Citibank report shows that the OECD countries face $78 trillion in unfunded pension liabilities. That is at least 50% more than their total GDP. Pension obligations are growing faster than GDP in most of those countries, if not all. Those are obligations on top of their total debt. By the way, most of those pension obligations are theoretically funded from future returns, which are going to be sparse to nonexistent. That means obligations are compounding significantly faster than the ability to pay them. Without serious adjustments to either benefits or funding, there is literally no hope of catching up. Thought exercise: In European countries where taxes are already more than 50% of GDP, where will they find an extra 5–10% to meet those future pension obligations? How long will younger generations tolerate carrying older generations when the government is taking two thirds of their paychecks? You can begin to see the scope of the problem. Sometime this year, world public and private debt plus unfunded pensions will surpass $300 trillion – not counting the $100 trillion in US government unfunded liabilities. Oops. These obligations simply cannot be paid. A time is coming when the market and voters will realize that these obligations cannot be met. Will voters decide to tax “the rich” more? Will they increase their VAT rates and further slow growth? Will they reduce benefits? No matter what they decide, hard choices will bring political turmoil, which will mean market turmoil. The Unthinkable Recession History shows it is more than likely that the US will have a recession in the next few years, although one doesn’t appear to be on the near horizon. But when it does come, it will likely blow the US government deficit up to $2 trillion a year. Obama took eight years to run up a $10 trillion debt after the 2008 recession. It might take just five years after the next recession to run up the next $10 trillion. Here is a chart my staff created in late 2016 using Congressional Budget Office data, showing what will happen in the next recession if revenues drop by the same percentage as they did in the last recession (without even counting likely higher expenditures this time). And you can add the $1.3 trillion deficit in this chart to the more than $500 billion in off-budget debt, plus higher interest rate expense as interest rates rise. Whether the catalyst is a European recession that spills over into the US, or one triggered by US monetary and fiscal mistakes, or a funding crisis in China, or an emerging-market meltdown, the next recession will be just as global as the last one. And there will be more build-up of debt and more political and economic chaos.

President Trump is a fairly controversial figure, but I think most of us can agree that Trump is going to make volatility great again. The Great Reset will bring an increase in volatility, and the correlation among asset classes will once again approach 1.0, as it did during 2008–2009. If I’m right about the growing debt burden, the recovery from the next recession may be even slower than the last recovery has been – unless the recession is so deep that we have a complete reset of all asset valuations. I don’t believe politicians and central banks will allow that. They will print and try to hold on as long as possible, thwarting any normal recovery, until markets force their hands. But then, I can think of at least three or four ways that politicians and central bankers could react during the Great Reset, and each will bring a different type of volatility and effects on valuations. Flexibility will be critical to successful investing in the future. (Excerpts from Skin in the Game - Unedited)

Sontag is about Sontag — Virtue is precisely what you don’t show by Nassim Nicholas Taleb May 27, 2017 I will always remember my encounter with the writer and cultural icon Susan Sontag, largely because it was on the same day that I met the great Benoit Mandelbrot. I took place in 2001, two months after the terrorist event, in a radio station in New York. Sontag who was being interviewed, was pricked by the idea of a fellow who “studies randomness” and came to engage me. When she discovered that I was a trader, she blurted out that she was “against the market system” and turned her back to me as I was in mid-sentence, just to humiliate me (note here that courtesy is an application of the Silver rule), while her female assistant gave me the look, as if I had been convicted of child killing. I sort of justified her behavior in order to forget the incident, imagining that she lived in some rural commune, grew her own vegetables, wrote on pencil and paper, engaged in barter transactions, that type of stuff. No, she did not grow her own vegetables, it turned out. Two years later, I accidentally found her obituary (I waited a decade and a half before writing about the incident to avoid speaking ill of the departed). People in publishing were complaining about her rapacity; she had to squeeze her publisher, Farrar Strauss and Giroud of what would be several million dollars today for a book advance. She shared, with a girlfriend, a mansion in New York City, one that was later sold for $28 million dollars. Sontag probably felt that insulting people with money inducted her into some unimpeachable sainthood, exempting her from having skin in the game. It is immoral to be in opposition of the market system and not live (like the Unabomber) in a hut isolated from it But there is worse: It is even more, much more immoral to claim virtue without fully living with its direct consequences and this will be the main topic of the chapter: exploiting virtue for image, personal gain, careers, social status, these kind of things –and personal gain is anything that does not share the downside of a negative action. By contrast with Sontag, I have met a few people who live their public ideas. Ralph Nader, for instance, leads the life of a monk, identical to the member of a monastery in the sixteenth century. The Public and the Private As we saw with the interventionistas, a certain class of theoretical people can despise the details of reality, and completely so. If you believe that you are right in theory, you can completely ignore the real world –and vice versa. And you don’t really care how your ideas affect others because your ideas make you belong to some virtuous status that is impervious to how it affects others. Likewise, if you believe that you are “helping the poor” by spending money on powerpoint presentations and international meetings, the type of meetings that lead to more meetings (and powerpoint presentations) you can completely ignore the individuals –the poor is some abstract reified construct that you do not encounter in your real life. Your efforts in conferences gives you a license to humiliate them in person. Hillary Monsanto-Malmaison, more commonly known as Hillary Clinton, found it permissible to heap abuse at secret service agents.[i] I was recently told that a famous socialist environmentalist who was part of the same lecture series abused waiters in restaurants, between lectures on equity and fairness. Kids with rich parents talk about “white privilege” at such privileged colleges as Amherst –but in one instance, one of them could not answer D’Souza’s simple and logical suggestion: why don’t you go to the registrar’s office and give your privileged spot to a minority student who was next in line? Hence the principle: If your private life conflicts with your intellectual opinion, it cancels your intellectual ideas, not your private life and If your private actions do not generalize then you cannot have general ideas This is not strictly about ethics, but information transfer. If a car salesman tries to sell you a Detroit car while driving a Honda, he is signaling that it may have a problem. The Virtue Merchants In about every hotel chain, from Argentina to South Africa, the bathroom with have a sign meant to gets your attention: “protect the environment”. They want you to hold off from sending the towels to the laundry and reuse them for a while, because avoiding excess laundry it saves them tens of thousand dollars a year. This is similar to the salesperson telling you what is good for you when it is mostly (and centrally) good for him. They, of course, love the environment but you can bet that they wouldn’t have advertised it so loudly had it not been been good for their bottom line. So these global causes: poverty (particularly children’s), the environment, justice for some minority trampled upon by colonial powers, or some unknown yet gender that will be persecuted; these global causes are now the last refuge of the scoundrel advertising virtue. But virtue is precisely what you don’t advertise. It is not an investment strategy. It is not a cost-cutting scheme. It is not a book selling (and worse, concert tickets selling) strategy. Now I have wondered why, by the Lindy effect, there was no mention of what is called virtue signaling in the texts. How could it be new? Well, it is not new, but was not seen as particularly prevalent in the past. Indeed, let’s check Matthew 5 and 6. “Be careful not to practice your righteousness in front of others to be seen by them. If you do, you will have no reward from your Father in heaven. “So when you give to the needy, do not announce it with trumpets, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and on the streets, to be honored by others. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward in full. But when you give to the needy, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your giving may be in secret. Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you.” Unpopular Virtue Virtue without courage is an aberration: in fact you see cowards endorsing a public face of “virtue” as defined by the mainstream media, because they are afraid of doing otherwise. Their cowardice leads them to avoid association with, say anti-Al Qaeda in Syria because some Saudi shill (or some AlQaeda promoter like Charles Lister) will accuse them of Putinism, racism, anti-democracy, or some accusation that will cause ostracism. The best virtue requires courage; accordingly it needs to be unpopular. If I were to describe the perfect virtuous acts, it would be to take currently frowned upon positions, those penalized by the common discourse (particularly when funded by lobbyists). Like fighting the Monsanto claims, and promotion through shills that they are “saving the children” with their poisonous products, so anyone opposing them becomes easily described as a baby killer. The more costly, the more virtuous the act — particularly if it costs you your reputation. When integrity conflicts with reputation, go with integrity. Other Virtues True virtue lies in being nice to those who are neglected by others, the less obvious cases, those people the grand charity business tends to miss, those causes that are not (yet) promotional. by Dan Niles

17 May 2017 CNBC At the start of each new year, there is one thing I hate doing above all others: Paying my home insurance. I always wonder, why on earth do I do this? I have never had any use for it — ever. Then last year, an illegal campfire was built in Garrapata State Park. We could see the flames from our home. By the end of it, that fire had burned 132,000 acres and became the most expensive wildfire in United States history. That is how many people have approached the current bull market, which has been going on for eight years — there's no need for portfolio insurance, right? With a return of 255 percent since the S&P 500 bottomed at 677 on March 9, 2009, the correct strategy in hindsight would have been to borrow as much money as you could and put it all into a long only S&P index fund. In hindsight, there was no need to worry about the European debt crisis, China currency devaluation, oil market collapse, or Brexit vote. The recoveries were always swift with new highs not far behind. As stocks continue to climb, this 98-month-old bull market seems to have the legs of a youngster. This is the second oldest bull in history. How long did the oldest bull market last? It was from October 1990 through March 2000, a whopping 114 months. Unfortunately, that ended with a 49-percent correction over roughly 2 ½ years. During the most recent full economic cycle that started in October 2002, the bull market lasted 60 months but in the span of 17 additional months, the market lost 57 percent during the correction. The S&P was actually down 13 percent on a price basis over the full economic cycle as can be seen in the table below. Now many of your reading this may say "Who cares, Dan? If I had held on through the downturns, I made back what I lost and then some." While this sounds good in theory, how many of you actually didn't sell when it looked like the world was headed into the second Great Depression and banks were failing? Did you think the government would let Lehman fail? The length of the current bull market is even more concerning when combined with the valuation of the market. For example, the Shiller S&P 500 cylical-adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (CAPE) which is based on average inflation-adjusted earnings from the previous 10 years is at 29x versus its average of 17x. But this is higher than at any time since the time periods surrounding 1929 and 2000. Looking at just this year, S&P 500 companies trade at an average price-to-earnings ratio of 21x times last 12 month earnings compared to a 10-year average of 16.5x. On the positive side, unemployment is low, interest rates are low, and the housing market is strong so the next recession doesn't seem near. Multiples can always go higher and it would not surprise me if stocks climb another 5 percent to 10 percent higher over the next six to 12 months if tax reform or infrastructure spending are passed. I remember stocks looking overvalued exiting 1998 and then the Nasdaq went up 86 percent in 1999, powering a 20-percent increase in the S&P. Much like the New England Patriots coming back from a 28-3 deficit to win the Super Bowl, anything is possible. However, investors need to be aware that, at these multiples and the age of the current bull market, that the next likely move of 10 percent to 20 percent in stocks maybe lower, not higher. The problem is, most of the time that crystal ball is not handy and you do not know exactly when the next market wildfire is coming.

As it turns out, my home was safe from that wildfire but underinsured. I will be upping our policy. In good times, it is easy to get caught up in trying to obtain everything. In bad times you realize you do not want to lose everything. Only time will tell how long this bull market can last but I can guarantee, you will want insurance when it ends. With Central Bank rates today near all-time lows and their aggregate balance sheets at all-time highs, governments won't be able to be the insurance policy they once were in 2001 or 2008 once the current bull market ends and the next recession/correction begins. Commentary by Dan Niles, founding partner of AlphaOne Capital Partners and senior portfolio manager of the AlphaOne Satori Fund. Previously, he was a managing director at Neuberger Berman, a subsidiary of Lehman Brothers. Excessive stability breeds instability down the road

by Mohamed El-Erian 15 May, 2017 Bloomberg View The smoother the road, the faster people are likely to drive. The faster they drive, the more excited they are about getting to their destination in good, if not record time; but, also, the greater the risk of an accident that could also harm other drivers, including those driving slower and more carefully. That is an appropriate analogy for the way unusually low financial volatility influences positioning, asset allocation and market prospects. And it holds for both traders and investors. The lower the market volatility, the less likely a trader is to be “stopped out” of a position by short-term price fluctuations. Under such circumstances, traders are enticed to put on on bigger positions and assume greater risks. What is true for one trader is often true for firms as a whole. Moreover, the approach is often underpinned by formal volatility-driven models such as VAR, or value at risk, that give the appearance of structural robustness. Patient long-term investors can also be influenced by unusually low volatility, whether they know it or not. Expected volatility is among the three major inputs that drive asset-allocation models, including the “policy portfolio” optimization approach used by quite a few foundations and endowments (the other two variables being expected returns and expected correlation). As the specifications of such expectations are often overly influenced by observations from recent history, the lower the volatility of an asset class, the more the optimizer will allocate funds to it. All this is to say that the recent decline in both implied and actual measures of volatility, including a VIX that recently touched levels not seen since 1993, is likely to encourage even greater risk taking both tactically and strategically, including bigger allocations to stocks, high yield bonds and emerging market assets. And both, at least in the short-term, will contribute to damping market volatility further. None of this would be particularly remarkable if the decline in volatility was not coinciding with notable fluidity in the global economy on account of economic, financial, geopolitical, institutional and political factors. From the North Korean nuclear threat and the rise of anti-establishment movements to allegations of Russian meddling in elections and yet-to-be properly explained behaviors of some economic variables (such as productivity, wages and inflation), among many other developments, the disconnect with the exceptionally low levels of volatility is attracting greater attention, though seemingly few portfolio adjustments as of now. What makes the situation even more intriguing is that the main policy instrument that has been used in recent years to repress financial volatility, unconventional monetary policy, is itself in transition. The U.S. Federal Reserve has stopped its quantitative easing program and now seems intent on normalizing interest rates, including at least two possible hikes in the remainder of 2017. It is also considering a program for an outright reduction in the size of its balance sheet. Meanwhile, the long-awaited economic strengthening in Europe is placing pressure on the European Central Bank to be less accommodating, raising interesting questions about the sequence of its QE tapering, forward policy guidance and interest rate hikes. The Bank of England is seeing inflation rise to its highest level in some years. Left unattended, all this could lead to some unpleasant market outcomes -- whose consequences would potentially impact excessive risk takers, with negative spillovers on those who have been more careful. Fortunately, there is an orderly economic and financial way to reconcile the disconnects, and without derailing the gradual normalization of monetary policy. As detailed in earlier articles, this process involves politicians enabling other policy-making entities, which have tools better suited to the challenges at hand, to deliver on their economic governance responsibilities. By achieving higher and more inclusive growth, such an overdue policy response would enhance economic prospects, allow for genuine financial stability, lessen the political pressures on economic institutions (particularly central banks) and help render national politics less toxic. But if the needed policy response continues to lag, this period of unusual market calm would end up as another data point in support of the “instability hypothesis” of the U.S. economist Hyman Minsky – that is, the simple yet powerful idea that excessive stability breeds unsettling instability down the road. Investors need to appreciate the disconnect that can emerge between the price of risk in the market and the actual risks. by Dean Curnutt Bloomberg View 2 May 2017 Amid an improbable level of calm in markets, it’s worth remembering what Victor Haghani, a partner at Long-Term Capital Management, said in early 1999 about the fund’s implosion, especially given that quiet markets are compelling trading strategies that capitalize on low levels of volatility.

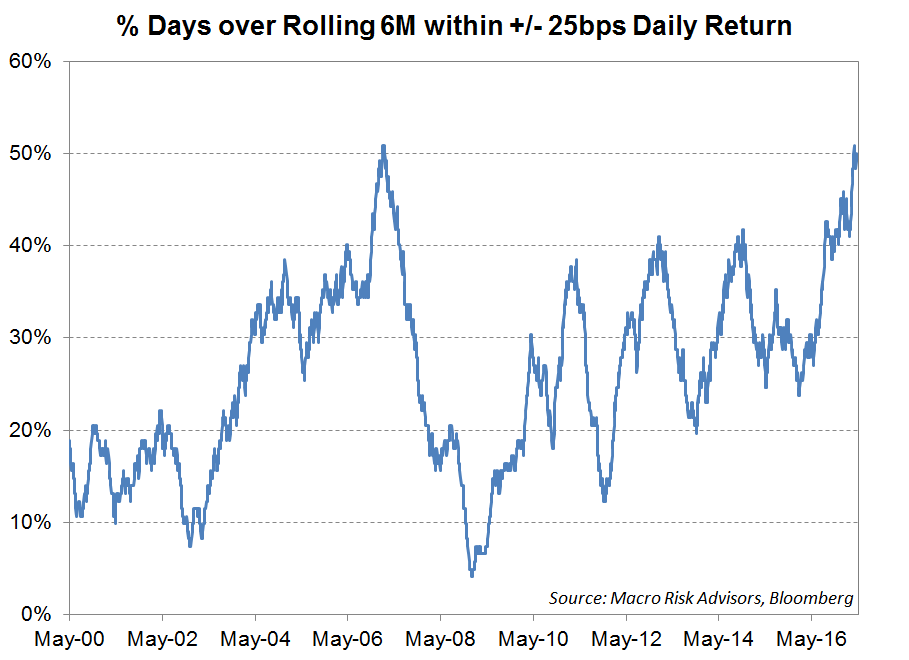

While Haghani’s statements were focused on the manner in which LTCM-specific trades were seemingly attacked by the market, they remain highly relevant today because the notion that financial market insurance is not like hurricane insurance is broadly applicable. When trades are especially crowded, their unwinding can amplify market moves as investors seek to de-risk in unison. Stable markets not only invite trades that bet on the continuation of stability, they almost force investors to pursue them in an investment climate so deprived of nominal return. Over the most recent six-month period, the realized volatility of the S&P 500 has been lower than at any time since before the financial crisis. Importantly, this period of market tranquility has generated huge profits for trading strategies that capitalize on stability by selling options. While there is an almost limitless supply of industry analysis on the current low level of the CBOE Volatility Index, or VIX, the real story has been the consistency with which the index has overstated the actual movement in the market. How low has volatility been? Over the last six months, more than half of the days have had a less than 25 basis-point return. These are “home run” results for option sellers. Even as markets appear stable, we should appreciate the risks. While Mother Nature dictates the timing and severity of the next hurricane, the financial market equivalent may arise endogenously, propelled by the forceful unwind of trades that enjoyed too much success for too long. Winning trades attract money, and as capital flows in to them, they become increasingly crowded. In markets, positioning matters. The Nomura Equity Volatility Risk Premium Fund, which systematically sells equity index variance swaps, has enjoyed quite a run. Since the U.S. election, it has lost money on just 27 percent of trading days. The average loss on such days has been a mere 19 basis points. The six month Sharpe Ratio of the strategy is north of 6. Strategies that make money nearly all the time, and only lose fractionally on the days they don’t are beyond appealing to investors.

The standard disclaimer “past performance is no guarantee of future results” tends to be ignored when strategies generate consistent profits with seemingly low risk. This is especially the case in a world bereft of interest income and as the expected future return prospects for the traditional 60/40 stock/bond portfolio appear unconvincing. With both stock and bond valuations at stretched levels, investors are being forced into “alternative risk premia” like the one offered by the Nomura fund. While the unprecedented market swings during the financial crisis imposed massive drawdowns on short volatility strategies, handsome profits have since been generated betting against a repeat of that market chaos. Over long periods of time, there are few trades that hold up as well as selling equity volatility. Faced with the daunting task of achieving 8 percent return targets, many pension funds have “bought the back-test” and are actively generating returns through short option strategies. Ten years after the early onset of the financial crisis, investors must appreciate the disconnect that can emerge between the price of risk in the market and the actual risks that may be in the process of materializing. In early 2007, the VIX dipped below 10, pulled down then -- like now -- by 6 percent realized volatility. Then, even as short volatility strategies profited from the very muted daily fluctuations in the S&P 500 Index, a tidal wave of systemic risk was already in motion. Over the first quarter of 2007, the mortgage industry began its collapse with a series of bankruptcies by subprime lenders. The severity of what would unfold over the next two years resulted from the one-sided positioning in the market that had built up over years based on faulty assumptions relating to credit risk and housing price appreciation. It is easy to argue that today’s financial system is safer than that of the pre-crisis era. Wall Street banks run with considerably less leverage than they did a decade ago. Further, the speculative excess in housing and the shadow bank securitization built around it is not nearly as prominent. These differences acknowledged, the current period and that of a decade earlier are similar in sharing a protracted decline in realized volatility. In one of the most ironic set of comments ever made by a policy maker, Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan said at the 2005 Jackson Hole confab -- with the VIX at 13, realized volatility at 8 and the CDX investment grade index at 50 -- that history “has not dealt kindly with the aftermath of protracted periods of low risk premiums.” Investors should heed those words. by Jeff Deist

Mises Wire May 2, 2017 Nassim Nicholas Taleb does not suffer fools gladly. Author of several books including The Black Swan and Antifragile, Taleb is known for his incendiary personality almost as much as his brilliant work in probability theory. Readers of his very active Medium page will experience a formidable mind with no patience for trendy groupthink, a mind that takes special pleasure in lambasting elites with no “skin in the game.” “Skin in the game” is a central (and welcome) tenet of Taleb’s worldview: we increasingly are ruled by an intellectual, political, economic, and cultural elite that does not bear the consequences of the decisions it makes on our (unwitting) behalf. In this sense Taleb is thoroughly populist, and in fact he correctly identified trends behind the Crash of ’08, Brexit, and Trump’s election. He understands that globalism is not liberalism, that identity and culture matter, and most of all that elites don’t understand how randomness and uncertainty threaten the inevitability of a global order. Thus Taleb argues the intelligentsia are not only haughty when they plan our future, they are also clueless: fragility abounds, and threatens to crash the Party of Davos. Hubris results from unearned wealth and prominence, coupled with a blindness to the Black Swans lying in wait. Born in Lebanon to a prominent family, educated at the University of Paris and Wharton, Taleb was poised to become part of the cognitive aristocracy he mocks. But he was never one of them. His hard-nosed persona, enhanced by a dedication to rigorous deadlift workouts, is quickly evident in his notorious interviews and very public Twitter brawls. His willingness to delve into history and religion sets him apart from the neoliberals who hope to wish them both away. Taleb writes for the intelligent everyman, and this blue-collar approach also extends to his description of himself as a “private intellectual, not a public one.” Austro-libertarians will find much to admire in his brilliant takedowns of the “pseudo-experts” he identifies in academia, journalism, politics, and science. But Taleb is no Austrian. While he holds a decidedly jaundiced view of most economists—calling for the Nobel in economics to be cancelled— he does not denounce economics as a field of study per se. Nor does he claim heterodox or reactionary inclinations: “I am as orthodox neoclassical economist as they make them, not a fringe heterodox or something. I just do not like unreliable models that use some math like regression and miss a layer of stochasticity, and get wrong results, and I hate sloppy mechanistic reliance on bad statistical methods. I do not like models that fragilize. I do not like models that work on someone's computer but not in reality. This is standard economics.” While he is not averse to using mathematics and statistics in economics, Austrians share his perspective that both are tools for economists. Statistical models are mostly bunk that provide no value to economic forecasters or investors, despite the highly paid Ivy League quants who produce them. In fact, models often have harmful effect of creating a false sense of relative certainty where none exists. It's refreshing to see Taleb make this claim so effectively from outside the Austrian paradigm of praxeology. But if his view of economics is mainline, his tone is Rothbard meets Hayek: I'm in favour of religion as a tamer of arrogance. For a Greek Orthodox, the idea of God as creator outside the human is not God in God's terms. My God isn't the God of George Bush. We know from chaos theory that even if you had a perfect model of the world, you'd need infinite precision in order to predict future events. With sociopolitical or economic phenomena, we don't have anything like that. Taleb does see a role for government, and supports consumer protection laws against predatory lending as one example. But he also purportedly supported Ron Paul in the 2012 presidential election, and has indeed mentioned Hayek as an influence regarding the dispersal of knowledge in society. He’s also applied special venom to several worthy targets in professional economics, including Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz, and Paul Samuelson. Taleb labels as “Stiglitz Syndrome” the process whereby public intellectuals suffer no financial or career consequences for being spectacularly wrong in their predictions. This is especially galling to a man who correctly called (and in fact became wealthy as a result of) economic crises in 1987 and 2008. In both instances, Taleb had “skin in the game” as a market trader. His own money and reputation were on the line, unlike the court economists in the New York Times. For an excellent (albeit indirect) analysis of how Austrians and libertarians can advance their cause from a minority position, Taleb’s recent article The Most Intolerant Wins: The Dictatorship of the Small Minority is a must-read. He reminds us that a small minority with courage—the most important form of skin in the game— can prevail over the slumbering masses. And he also reminds us that courageous individual actors, not 51% mass movements, drive real changes in every society: The entire growth of society, whether economic or moral, comes from a small number of people. So we close this chapter with a remark about the role of skin in the game in the condition of society. Society doesn’t evolve by consensus, voting, majority, committees, verbose meeting, academic conferences, and polling; only a few people suffice to disproportionately move the needle. All one needs is an asymmetric rule somewhere. And asymmetry is present in about everything. Economics is lost, mired in a quicksand of predictive models that fail to predict and macro-analysis that fails to analyze. Democratic politics is lost, ruined by bad actors with perverse incentives to burn capital rather than accumulate it. And academia is lost, still stuck in a centuries-old model run by hopelessly sheltered PhDs. Taleb gets all of this, and does an admirable job of explaining it. Austro-libertarians would be wise to see him as a valuable ally and voice in the ongoing fight against states, central banks, and planners of all stripes. Jeff Deist is president of the Mises Institute. He previously worked as a longtime advisor and chief of staff to Congressman Ron Paul. by Nicholas Colas, Chief Market Strategist

Convergex May 2, 2017 “It’s quiet out there… too quiet.” That old line, its origins lost to history, neatly sums up how many equity traders feel right now. Global equities continue their remarkable rally in the most unremarkable of ways. Slow, and steady and boring. The CBOE VIX Index briefly broke 10 today, essentially half of its long run average of 19.6, and closed at 10.11. In its unofficial role as the primary forecasting tool of near term US equity volatility, that is the equivalent of a Los Angeles weather forecast. 80 degrees and sunny… Next weather update in 5 days. I got to wondering just how many days the VIX has closed below 10 and what that means for future equity returns. The answers:

The takeaway from these examples is clear: in the unusual instances (just 0.13% of the days since 1990) when the VIX closes below 10, one year forward returns have all been negative. In one case (2007 into 2008) the following year was terrible. In the other case (1994 into 1995) it was great – up 37.2%. If you want to see a history of S&P 500/3 month T-bills/10 year Treasury note returns (very useful when looking at historical trends such as these), click here: http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/histretSP.html Important: the upshot of this quick analysis is this: a VIX close below 10 is historically correlated with a one year pause in S&P 500 returns. The year after that is where things get dicey. You could get a 1995 (+37%) or a 2008 (down 37%). Now, 3 (2 and half, if we’re being honest) examples isn’t a great sample size. To round out the discussion we need to come to some conclusions about WHY US equity volatility is so low. And what might change that. Here are 10 equity “Puts”: commonly held investor beliefs about current market dynamics that help explain both low volatility and the march higher for US and global equities. #1) The Fed Put. Ever since Alan Greenspan came to the US equity market’s rescue after the October 1987 crash, there has been a school of thought that says the US Federal Reserve views equity markets as a “Third mandate” along with price stability and full employment. If markets falter, the Fed will pass on a June rate increase and perhaps those scheduled for later in the year as well. Or so the logic goes… #2) The ECB Put. To the degree to which the European Central Bank has mimicked the Fed’s policies of ultralow interest rates and the purchase of long dated bonds (quantitative easing), equity investors may well feel that there is also an ECB “Put”. #3) “Long End of the Yield Curve” Put. If global economic growth is about to take a step function higher (as indicated by rallies in US, EAFE and Emerging Market equities) no one seems to have told sovereign debt markets. The US 10 year note for example, yields all of 2.3% and the 10 year German Bund pays a 0.3% coupon. Those low rates help support equity valuations, and if global growth falters those rates will go lower still (and continue to help valuations). #4) “Trump/Republican Washington” Put. At some point before the mid-term US elections in 2018, President Trump and the GOP – controlled Congress should be able to pass tax reform. That gives equity investors the chance to see earnings estimates rise for 2018 and beyond, supporting current valuations. #5) “Passive Money/ETF Flow” Put. Year to date money flows into equity US listed Exchange Traded Funds total $121 billion, a pace that will break all prior records if it continues through the end of 2017. Moreover, those flows are remarkably consistent whether you look at the last day, week, month, quarter to date or calendar year. As long as those trends continue, why worry about a market correction? #6) “Offshore/Corporate Cash” Put. US public companies continue to operate at near-record profit margins, but they are still more likely to buy back their own stock or hold cash offshore rather than invest in their business with those cash flows. That leaves them less prone to financial stress during an economic downturn and therefore reduces their stock price volatility across the business cycle. Also worth considering: if corporate tax reform does come through, these same companies may be able to repatriate some of their offshore cash holdings for buybacks (which would also reduce price volatility, everything else equal). #7) “Lower Sector Correlation” Put. Since the November US elections, sector correlations within the S&P 500 have dropped from +90% to 55-60%. Should this continue (and absent a major correction, it should), overall S&P 500 volatility will remain lower than when correlations were higher. #8) “Earnings Beats GDP” Put. As it stands right now, the S&P 500 will post close to a 10% earnings growth rate for Q1 2017. Part of that is from smaller losses in the Energy sector, and part is actual earnings growth in Financials, Materials, and Tech stocks. All of it is enough to allow analysts to expect Q2 2017 earnings growth to run 8%, even though Q1 US GDP growth only showed 0.7% growth when it was released last Friday. #9) “Receding Nationalism” Put. Now that equity investors seem certain Marine Le Pen will not be the next French president, the prospects for a “Frexit” seem distant. Polls currently have her at 40% of the vote versus Macron’s 60%. See here for a good poll tracker: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-39692961 #10) “GDP Bounce Back” Put. After a lackluster Q1 GDP print, the closely watched (and accurate for Q1) Atlanta Fed GDP Now model has a 4.3% starting estimate for Q2 2017. Blue chip economists are sitting closer to 2.7%, but all agree for the moment that Q2 will be far better than Q1. I could go on, but you get the point: there is an overwhelming market narrative that equates to “Don’t worry, be happy”. That should be no surprise. You don’t end up with a 10 handle VIX very often, and when you do it is the result of a unique set of circumstances. I will close where I began, with the possibility of a single digit VIX reading. Historically, that signals the possibility of a pause in equity returns. This means at least a few of our 10 “Puts” will not actually work as anticipated. But the real question is not 2017 – it is 2018. Will next year resemble 1995 (+37%) or 2008 (-37%). Again, that comes down to how many of these “Puts” survive the next 12 months. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed