|

February 13, 2015

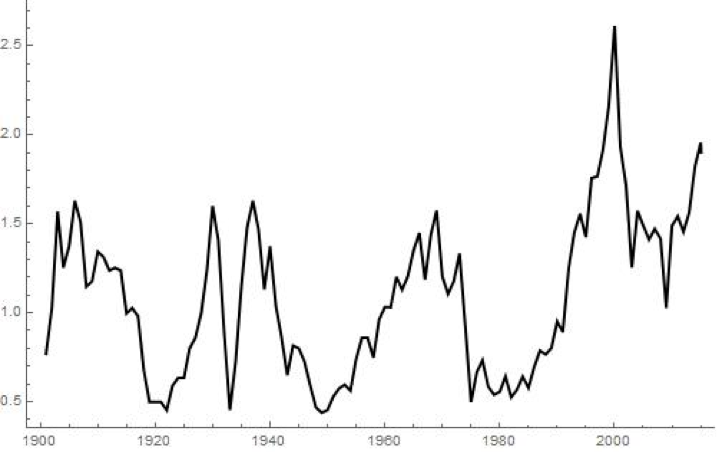

Forbes Excerpts from Bill Ackman's Boys & Girls Harbor Investment Conference: When asked about the current market environment, Dalio said he is worried about so-called tail risks, unexpectedly severe market moves like the 2008 crisis, as the Federal Reserve contemplates a rise in interest rates. With investors chasing ever scanter yields and driving up the price of perceived safe assets like U.S. stocks, bonds and real estate, Dalio said “what I think going forward over the next few years is that the risk of a downside is material.” Furthermore, Dalio said he believes expectations for corporate profits are running far too high and not accounting for the drag of rising rates. He characterized profit margin expectations as ”unsustainable” and argued asset prices are at risk over the next three years. “I always think about what is the biggest tail risk,” Dalio said before stating Bridgewater is long bond exposure. If Dalio is correct in his view of rising rates and declining profit margins, one of those “risk of ruin” or “risk of not coming back” nightmares he fears, it will have a dramatic negative impact on the work that activists like Ackman undertake. Dalio’s forecast of declining profit margins would cast a pall over the standalone, leveraged businesses that activist investors have created in recent years. But he could also be wrong. by Mark Spitznagel: Mark Spitznagel is the founder and chief investment officer of Universa Investments, and the author of “The Dao of Capital.”

The New York Times February 13, 2015 Project Syndicate

by Mohamed El-Erian February 10, 2015 LAGUNA BEACH – Six and a half years after the global financial crisis, central banks in emerging and developed economies alike are continuing to pursue unprecedentedly activist – and unpredictable – monetary policy. How much road remains in this extraordinary journey? In the last month alone, Australia, India, Mexico, and others have cut interest rates. China has reduced reserve requirements on banks. Denmark has taken its official deposit rate into negative territory. Even the most stability-obsessed countries have made unexpected moves. Beyond cutting interest rates, Switzerland suddenly abandoned its policy of partly pegging the franc's value to that of the euro. A few days later, Singapore unexpectedly altered its exchange-rate regime, too. More consequential, the European Central Bank has committed to a large and relatively open-ended program of large-scale asset purchases. The ECB acted despite a growing chorus of warnings that monetary stimulus is not sufficient to promote durable growth, and that it encourages excessive risk-taking in financial markets, which could ultimately threaten economic stability and prosperity (as it did in 2008). Even the US Federal Reserve, which is presiding over an economy that is performing far better than its developed-world counterparts, has reiterated the need for "patience" when it comes to raising interest rates. This stance will be difficult to maintain, if continued robust job creation is accompanied by much-needed wage growth. This new round of central-bank activism reflects persistent concerns about economic growth. Despite a once-unthinkable amount of monetary stimulus, global output remains well below potential, with the potential itself at risk of being suppressed. Making matters worse, weak demand and debt overhangs are fueling concerns about deflation in the eurozone and Japan. Anticipating falling prices, households could postpone their consumption decisions, and companies could defer investment, pushing the economy into a downward spiral from which it would be very difficult to escape. If weak demand and high debt were the only factors in play, the latest round of monetary stimulus would be analytically straightforward. But they are not. Key barriers to economic growth remain largely unaddressed – and central banks cannot tackle them alone. For starters, central banks cannot deliver the structural components – for example, infrastructure investments, better-functioning labor markets, and pro-growth budget reforms – needed to drive robust and sustained recovery. Nor can they resolve the aggregate-demand imbalance – that is, the disparity between the ability and the willingness of households, companies, and governments to spend. And they cannot eliminate pockets of excessive indebtedness that inhibit new investment and growth. It is little wonder, then, that monetary-policy instruments have become increasingly unreliable in generating economic growth, steady inflation, and financial stability. Central banks have been forced onto a policy path that is far from ideal – not least because they increasingly risk inciting some of the zero-sum elements of an undeclared currency war. With the notable exception of the Fed, central banks fear the impact of an appreciating currency on domestic companies' competitiveness too much not to intervene; indeed, an increasing number of them are working actively to weaken their currencies. The "divergence" of economic performance and monetary policy among three of the world's most systemically important economies – the eurozone, Japan, and the United States – has added another layer of confusion for the rest of the world, with particularly significant implications for small, open economies. Indeed, the surprising actions taken by Singapore and Switzerland were a direct response to this divergence, as was Denmark's decision to halt all sales of government securities, in order to push interest rates lower and counter upward pressure on the krone. Of course, not all currencies can depreciate against one another at the same time. But the current wave of efforts, despite being far from optimal, can persist for a while, so long as at least two conditions are met. The first condition is America's continued willingness to tolerate a sharp appreciation of the dollar's exchange rate. Given warnings from US companies about the impact of a stronger dollar on their earnings – not to mention signs of declining inward tourism and a deteriorating trade balance – this is not guaranteed. Still, as long as the US maintains its pace of overall growth and job creation – a feasible outcome, given the relatively small contribution of foreign economic activity to the country's GDP – these developments are unlikely to trigger a political response for quite a while. Indeed, America's intricate trade relations with the rest of the world – which place households and companies on both sides of the production and consumption equation – make it particularly difficult to stimulate significant political support for protectionism there. The second condition for broad-based currency depreciation is financial markets' willingness to assume and maintain risk postures that are not yet validated by the economy's fundamentals. With central banks – the de facto best friend of financial markets these days – pushing for increasingly large financial risk-taking (as a means of stimulating productive economic risk-taking), this is no easy feat. But, given the danger that this poses, one hopes that they succeed. In any case, central banks will have to back off eventually. The question is how hard the global economy's addiction to partial monetary-policy fixes will be to break – and whether a slide into a currency war could accelerate the timetable. by Guy Haselman

Scotiabank Feburaury 5, 2015 Central bank polices have ruptured the proper functioning of capital markets. Policy over-reach with gargantuan experimentation has, and continues, to fuel extreme mispricing of risk and mis-allocation of resources. Soaring market volatilities with wild daily gyrations are a symptom. A battle is raging between the non-believers (doubters of policy success) versus those clinging to the hope that a soft landing can someday be engineered. Some investors have little choice but to play along. Some investors only participate reluctantly. Yet, other investors move to cash or cash-equivalents, while looking for better ‘places to hide’. For the growing number of non-believers, the secret sauce today is trying to find non-correlated sources of idiosyncratic risk where adequate compensation is offered for that risk. So what do investors do in a ZIRP/NIRP world (Zero/Negative Interest Rate Policy)? Why would anyone pay money to lend money? Buyers are typically those who are mandated to do so: passive indexers, some bond funds, LDI pensions or insurance companies. Some of them, however, are locking into losses that will at some point have terrible consequences (e.g., an insurance company who sold an annuity product several years ago that guarantees, say, a 4% return). Investors who are not mandated, and who do not wish to lock into losses, are incentivized to take risk. They either have to move out the curve, assuming duration risk, or they move down the capital structure, assuming credit risk. Since investors only receive a trivial yield boost by increasing duration or credit risk, many investors have instead moved further up the risk spectrum to equities. The justification is often, ‘equities have upside, while bonds are capped at par’: such a comment does not take risk into account. QE programs turbo charge the chase for yield because central banks hoard the safest assets. Those who sell securities to the central bank need to replace those assets, but reinvestment into an asset that yields a similar return often means moving into a riskier security.There are some fixed income managers who now get their fixed income exposures through dividend paying stocks. Speculators who buy negative yielding bonds only do so in the belief that they will be able sell them at an even more negative yield. With negative yields on some deposit accounts and on highly-rated securities, investors have to decide if they want to pay money for safety, or pay to avoid risk. Most decide to chase positive return (risk), causing many to extend beyond their historical risk preferences and for which many are ill-suited. Aggressive central bank activity and implicit promises have led to behavioral changes where investors have become fearful of missing out on the easy returns of markets that are perceived to rise perpetually (as long as the Fed doesn’t hike). Finland became the first country to issue debt as long as 5 years in the primary market at negative yields. In the secondary market, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and The Netherlands have negative yields on debt trading out to 5 years. Nestles became the first corporation to have a negative yielding bond. As policy rates and bond yields plummet, and as equity markets power to new highs, investors need to recognize that future expected returns decrease, because (for the most part) rising markets shrink upside potential, while enlarging downside potential. Nonetheless, some investors myopically believe that ‘money printing needs a home’ and that it will end up in equities (the asset class with upside). However, such a belief needs to include a deep faith in the central bank’s abilities to navigate a soft landing. History is not on their side. Investors pouring into equities might be playing an epic game of chicken. There are significant consequences of ZIRP and NIRP. Money market funds, pensions, insurance companies, savers, or those who live on a fixed income, are punished at the expense of the debtor. Low rates imply less household disposable income for creditors and more disposable income for debtors. Capital accumulation and savings - that would normally reduce overall debt levels – is discouraged. The original premise behind the QE programs and other types of extreme monetary accommodation was to lower leverage and reduce the high levels of indebtedness that caused the 2008 crisis. In this light, measuring the success of central bank’s extraordinary policies should include the progress made in lower indebtedness to safer levels. Since global indebtedness has risen materially, it can be argued that levels of financial instability have actually risen and central bank policies are to blame. Consultancy firm McKinsey & Co just issued a report finding that global levels of indebtedness have increased from $142 Trillion in Q4 2007 to $199 Trillion in Q2 2014 with debt as a share of GDP rising from 270% to 286%. Debt is being added at a faster rate than GDP. Policy makers are borrowing from the future to solve the short term problems of today. The result is unstable future outcomes and ballooning risks to market stability; concurrent with complacent investors unwittingly scramble for paltry returns. Holding cash has never looked so good. “We’ll be fighting in the streets / with our children at our feet / and the moral that they worship will be gone.” – The Who by Paul Singer

Elliott Management Investor Letter Excerpts: The world believes it is in a sweet spot. There is global consensus that central banks know what they are doing and are in control, and that if economies falter, a bigger dose of QE or ZIRP or NIRP (negative interest rate policy – we just made that one up) will keep it from getting out of hand. Additionally, there seems to be a universally held belief that the U.S. is unquestionably the safe haven for the foreseeable future, that its financial crisis and long recession are behind it and that China has complete control over its own destiny. It may not surprise you to learn that we either disagree with or remain unconvinced about every one of the foregoing propositions. Conditions in the global economy are clearly abnormal. The policymaker response to those conditions is extraordinary, with minimal focus on an all-out push for higher growth. Instead, the primary focus is on boosting “inflation” with repeated doses of bondbuying, stock-buying and super-low interest rates. We cannot appreciate why policymakers are not jumping up and down clamoring for structural pro-growth reforms and policies, and why there is a compliant consensus that the only policy that is possible is more monetary easing. Apparently, most politicians are happy to leave the hard economic and policy decisions to their central banks instead of introducing legislation to properly address the world’s economic problems. It is impossible to assess what will change or destroy the consensus that current policies will hold the global economy and financial system afloat forever, but when assessing the scope and shape of risks to our assets, it is most useful to match them to the size of the aberrations which could cause reversal or surprise. Today, those potential changes are strikingly large. We have frequently said that real deflation (price and credit collapse, not a tiny downturn in aggregate prices or “insufficient” inflation) is impossible. Governments are too alert to that possibility, have no compunction about debasing their currencies and will simply not stand for seriously-falling prices. The issue of real inflation, at the other end of the spectrum, is deemed by just about everyone but us, plus a few beleaguered stragglers and fellow travelers who “didn’t get the memo,” to be a non-issue into the future as far as one can peer. We are a little bit more simpleminded than the consensus-buyers who are looking just ahead. They think there is slack in the global economy, workers do not have pricing power and inflation is something that governments always will need to boost and push just to reach their (arbitrary) targets. We, on the other hand, are most focused on the combination of the trustworthiness of governments to protect the value of paper money (which has never been lower than at present), plus the structural impediments and barriers to smoothly functioning growth, innovation, entrepreneurship and private-sector job creation. Confidence in policymakers and central bankers today should be low or nonexistent, but confidence has not (yet) been lost. Leadership in the developed world is weak and confused, except for President Putin (although his is not the kind of strong leadership that we have in mind as a model for bringing the developed world out of its torpor). It is for this reason that we are not complacent, because we can easily imagine a transition from the current post-2008 context to a different and scarier environment. Recent abrupt and intense trading shakeouts give some hint of the potential power and violence that resides in modern, over-leveraged, technologically wired markets, and confidence in paper money and central bankers can be lost at any moment. When it is, and what that development will look like, are mysteries. The difference between “us” and “them” is that we are trying hard to figure out what is essentially unknowable and impossible to ascertain, while most people are just shrugging and accepting the current calm as a given. Government action is obviously a more powerful contributor to the trading context in many areas than ever before, and it is also true that a good amount of government action is increasingly arbitrary, ideologically driven and arguably lawless, even in the most developed countries. This factor is hard to quantify and mitigate in risk management, but traders who wish to preserve their capital “no matter what” need to take it into account in their trading and risk controls. These are the considerations that are front and center in our strategic assessment of the trading landscape: trying to make sure that a sudden loss of confidence in paper money, or in any of the major markets in which we trade, does not unacceptably jostle our portfolio; keeping dry powder for the inevitable moment when the next flood of distressed securities becomes available at reasonable prices; and being cautious and visionary about the regulatory landscape in order to be cognizant of regulatory directions as well as where regulators are focusing today. Our mix of strategies is a good one, and we need to keep making the research and analysis process more and more robust. This effort is key to making sure that the next trading crisis does not surprise us in major ways. In the last few years, thanks to QE and ZIRP, the common investor has made very good returns despite the lack of solid growth in the global economy. Such an imbalance between economic growth and good investment returns for both stocks and bonds is abnormal and unsustainable for extended periods of time. We at Elliott aim to make at least some money in every environment, with a combination of activities emphasizing complexity and manual effort, including activism. Thus, a period such as the most recent few years masks the benefits of exerting the effort (and accepting the costs) to hedge rather than not, and to try to make things happen rather than passively ride the wave. We are certainly not complaining, but merely observing these factors, and further speculating that the time may be near when complacency in the stock and bond investing community may be seriously jostled. We design our positions so that they will, in most cases, be governed more or less by their own idiosyncratic paths, even in periods of disruption. We of course recognize that events and resolutions will be affected in various measures by macro developments, and that liquidity considerations in adverse market conditions will impact even completely uncorrelated positions. One very clear implication of the diminished liquidity in markets due to the withdrawal of a great deal of position-taking capital is that the punishment for being wrong has become more severe. We suppose the other side of the coin is that aberrations which can create attractive trades can also be larger and more compelling, given the reduced participation from Wall Street prop desks. ... Markets are not getting more efficient; indeed, the press of money and zero-percent interest rates doth not efficiency make. People should have learned that lesson in 2006-08, but they did not (much to their ultimate peril, we think). And here we are again. by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

The Telegraph February 4, 2015 China is trapped. The Communist authorities have discovered, like the Japanese in the early 1990s and the US in the inter-war years, that they cannot deflate a credit bubble safely. A year of tight money from the People's Bank and a $250bn crackdown on shadow banking have pushed the Chinese economy close to a debt-deflation crisis. Wednesday's surprise cut in the Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR) - the main policy tool - comes in the nick of time. Factory gate deflation has reached -3.3pc. The official gauge of manufacturing fell below the "boom-bust" line to 49.8 in January. Haibin Zhu, from JP Morgan, says the 50-point cut in the RRR from 20pc to 19.5pc injects roughly $100bn into the system. This will not, in itself, change anything. The average one-year borrowing cost for Chinese companies has risen from zero to 5pc in real terms over the past three years as a result of falling inflation. UBS said the debt-servicing burden for these firms has doubled from 7.5pc to 15pc of GDP. Yet the cut marks an inflection point. There will undoubtedly be a long series of cuts before China sweats out its hangover from a $26 trillion credit boom. Debt has risen from 100pc to 250pc of GDP in eight years. By comparison, Japan's credit growth in the cycle preceding its Lost Decade was 50pc of GDP. The People's Bank may have to cut all the way to zero in the end - a $4 trillion reserve of emergency oxygen - but to do that is to play the last card. Wednesday's trigger was an amber warning sign in the jobs market. The employment component of the manufacturing survey contracted for the 15th month. Premier Li Keqiang targets jobs - not growth - and the labour market is looking faintly ominous for the first time. Unemployment is supposed to be 4.1pc, a make-believe figure. A joint study by the International Monetary Fund and the International Labour Federation said it is really 6.3pc, high enough to cause sleepless nights for a one-party regime that depends on ever-rising prosperity to replace the lost elan of revolutionary Maoism. Whether or not you call it a hard-landing, China is struggling. Home prices fell 4.3pc in December. New floor space started has slumped 30pc on a three-month basis. This packs a macro-economic punch. A study by Jun Nie and Guangye Cao for the US Federal Reserve said that since 1998 property investment in China has risen from 4pc to 15pc of GDP, the same level as in Spain at the peak of the "burbuja". The inventory overhang has risen to 18 months compared with 5.8 in the US. The property slump is turning into a fiscal squeeze since land sales make up 25pc of local government money. Zhiwei Zhang, from Deutsche Bank, says land revenues crashed 21pc in the fourth quarter of last year. "The decline of fiscal revenue is the top risk in China and will lead to a sharp slowdown," he said. The IMF says China's fiscal deficit is nearly 10pc of GDP once land sales are stripped out and all spending included, far higher than generally supposed. It warned two years ago that Beijing was running out of room and could ultimately face "a severe credit crunch". The gears are shifting across the Chinese policy spectrum. Shanghai Securities News reported that 14 Chinese provinces are preparing a $2.4 trillion blitz on infrastructure to combat the downturn, a reversion to the same policies of reflexive stimulus that President Xi Jinping forswore in his Third Plenum reforms. How much of this is new money remains to be seen but there is no doubt that Beijing is blinking. It may be right to do so - given the choice of poisons - yet such a course stores up even greater problems for the future. The China Development Research Council, Li Keqiang's brain-trust, has been shouting from the rooftops that the country must take its post-debt punishment "as soon possible". China is not alone in facing this dilemma as deflation spreads and beggar-thy-neighbour currency wars become the norm. Fifteen central banks have eased monetary policy so far this year. Denmark's National Bank has cut rates three times in two weeks to -0.5pc in an effort to defend its euro-peg, the latest casualty of the European Central Bank's €1.1 trillion quantitative easing. The Swiss central bank has been blown away. Asia is already in a currency cauldron, eerily like the onset of the 1998 crisis. The Japanese yen has fallen by half against the Chinese yuan since Abenomics burst upon the Pacific Rim. Japanese exporters pocketed the windfall gains of devaluation at first to boost margins. Now they are cutting prices to gain export share, exporting deflation. China's yuan is loosely pegged to a rocketing US dollar. Its trade-weighted exchange rate has jumped 10pc since July. This is eroding the wafer-thin profit margins of Chinese companies and tightening monetary conditions into the downturn. David Woo, from Bank of America, says Beijing may be forced to join the currency wars to defend itself, even though this variant of the "Prisoner's Dilemma" leaves everybody worse off. "We view a meaningful yuan devaluation as a major tail-risk for the global economy," said. If this were to happen, it would send a deflationary impulse worldwide. China spent $5 trillion on fixed investment last year, more than Europe and America combined, increasing its overcapacity in everything from shipping to steels, chemicals and solar panels, to even more unmanageable levels. A yuan devaluation would dump this on everybody else. It would come at a moment when Europe is already in deflation at -0.6pc, and when Britain and the US are fast exhausting their inflation buffers as well. Such a shock would be extremely hard to combat. Interest rates are already zero across the developed world. Five-year bond yields are negative in six European countries. The 10-year Bund has dropped to 0.31. These are no longer just 14th century lows. They are unprecedented. My own guess is that we would have to tear up the script and start printing money to build roads, pay salaries and fund a vast New Deal. This form of helicopter money, or "fiscal dominance", may be dangerous, but not nearly as dangerous as the alternative. China faces a Morton's Fork. Li Keqiang has made it his life's mission to stop his country drifting into the middle income trap. He says himself that the investment-led model of past 30 years is obsolete. The low-hanging fruit of catch-up growth has been picked. For two years he has been trying to tame the state's industrial behemoths, and trying to wean the economy off credit. Yet virtuous intent has run into cold reality. It cannot be done. China passed the point of no return five years ago. Weekly Market Comment

by John P. Hussman, Ph.D. February 2, 2015 The combination of widening credit spreads, deteriorating market internals, plunging commodity prices, and collapsing yields on Treasury debt continues to be most consistent with an abrupt slowing in global economic activity. Generally speaking, joint market action like this provides the earliest signal of potential economic strains, followed by the new orders and production components of regional purchasing managers indices and Fed surveys, followed by real sales, followed by real production, followed by real income, followed by new claims for unemployment, and confirmed much later by payroll employment. Stronger conclusions, particularly about the U.S. economy, will require more evidence, but from a global perspective, these pressures are already quite evident. It’s striking how little economic thought seems to go into talking-head assessments of these developments. The plunge in Treasury yields, for example, is attributed to yield-seeking in response to expectations of European Q-ECB. But if investors still retained speculative yield-seeking preferences, we would observe that uniformly through similar yield-seeking in lower quality credit, as well as risk-seeking in equities without large internal divergences (factors that serve as the central distinction between overvalued markets that continue to advance, and overvalued markets that drop like a rock – see A Most Important Distinction). Instead, the broad retreat – though still early – from speculative assets toward havens considered free of default, essentially signals a shift toward risk aversion. Bad things tend to happen when compressed risk premiums meet increasing risk aversion. As I’ve frequently noted, risk premiums tend to normalize in spikes, so low and expanding risk premiums are the root of abrupt market losses. While Wall Street talking heads seem unanimous in viewing the decline in oil prices as “stimulative” for the global economy, on the notion that it frees up spending money for other purposes, the problem is that the decline in oil prices is indicative of a retreat in global demand. That is, when prices fall, it makes a difference whether the decline is due to an expansion of supply (which lowers price but expands output), or a retreat in demand (which also lowers price but contracts output). If the demand curve shifts back, you don’t take the lower price that resulted from the reduction of demand, and then use it as an argument that demand is going to increase (and then use that as an argument that increased demand will raise the price, and then…) No. The decline in price is itself an equilibrium outcome of the decline in demand. At that point, you end the sentence. Unfortunately for monetary authorities around the world, the same is true for interest rates here. Attempts to press interest rates to preposterously low levels aren’t stimulating demand for borrowing, because the global economy is already submerged in its own indebtedness. Yes, before investor preferences shifted toward risk aversion in about mid-2014, depressed yields on safer investment classes did create an opportunity for really junky issuers to issue debt to yield-seeking investors by offering a “pickup” above Treasury yields. We saw the same thing during the housing bubble, which allowed an enormous amount of malinvestment funded by yield-seeking. In the recent cycle, the malinvestment has primarily taken the form of leveraged loans (loans to already highly-indebted borrowers), and “covenant-lite” junk lending. The other primary form of malinvestment has been through corporate repurchases of equities that are strenuously overvalued on historically reliable measures, financed – make no mistake – through the issuance of new debt (see The Two Pillars of Full Cycle Investing for the data on this). So what we’ve really got is a situation where interest rates are low because safer borrowers are swimming in debt, while credit spreads are widening because junkier borrowers are hugely sensitive to even a moderate slowing in global economic activity. We generally agree with Charles Plosser, one of the more economically thoughtful minds at the Federal Reserve, who observed last week: “The history is that monetary policy is not ultimately a very effective tool at solving real economic structural problems. It can try for a while but the problem then is that it’s only temporarily effective, and when you can’t do it anymore you get the explosion yesterday in the Swiss market. One of the things I’ve tried to argue is look, if we believe that monetary policy is doing what we say it’s doing and depressing real interest rates and goosing the economy, and we’re in some sense distorting what might be the normal market outcomes, at some point we’re going to have to stop doing it. At some point the pressure is going to be too great. The market forces are going to overwhelm us. We’re not going to be able to hold the line anymore. And then you get that rapid snapback in premiums as the market realizes that central banks can’t do this forever. And that’s going to cause volatility and disruption.” That’s already an issue at present. If we were still in an environment where investors were risk-seeking (which we infer from the uniformity of market internals, credit spreads, and other risk-sensitive market action), overvalued markets might have a tendency to become more overvalued, regardless of how thin risk premiums might be. That, right there, is the essential lesson to be drawn from our own challenges in the recent half-cycle, at least until about June of last year when we viewed them as fully addressed (see A Better Lesson Than “This Time is Different” – probably the best reference on that awkward transition). But once internals and credit spreads deteriorate, as they have been doing in recent months, compressed risk-premiums have a tendency to normalize - not gently, but in spikes, which we observe in price action as air-pockets, free-falls, and crashes. Where I think Plosser and I might disagree is that, in my view, the first step by the Federal Reserve should not be to raise interest rates – indeed, in the face of what we view as a clear deterioration in global economic prospects, I question that this would be particularly constructive – and would cast a great deal of blame toward the Fed if the weakness continues. Not to say that raising rates would have much actual effect on economic activity, as the only form of economic activity that has proved responsive to zero-interest rate policy are those activities where interest itself is the primary cost of doing business: financial speculation and leveraged carry trades. But hiking rates by paying interest on reserves, rather than by normalizing the monetary base, would have no promising effects. In my view, the primary response to a hike in the Fed Funds rate (achieved by raising the interest rate paid on reserves) would be to draw currency out of circulation and expand the already grotesque mountain of idle reserves in the banking system. Rather, I think the Fed should – and should immediately – cease the reinvestment of principal as assets on the Fed’s balance sheet mature. There’s utterly no sense to these reinvestments, as 1) the balance sheet could contract by about $1.4 trillion without moving short-term interest rates from zero (see A Sensible Proposal and a New Adjective), and 2) at the present 10-year Treasury yield of 1.64% and interest on reserves of 0.25%, the breakeven curve on new bond purchases by the Fed – the future yields that would result in zero total returns, even after interest income – are just 1.81% on a 1-year horizon, 2.02% on a 2-year horizon, and 2.29% on a 3-year horizon. Future yields any higher than that will produce net losses to the Fed. Now, my impression is that yields may move even lower over the next few quarters if the economy weakens, in which case we might even see a 1-handle on the 30-year bond and a 0-handle on the 10-year. But bonds are already priced at speculative levels in the sense that one must expect virtually no normalization of yields at all, for years to come, if one is to avoid net losses on purchases at these levels. As usual, our own approach leans toward seeking longer duration on upward spikes in yields, and avoiding long-duration exposures on overextended retreats in yield. In short, 10-year Treasury bonds are priced to be feeble long-term investments, as are nearly all other investment classes thanks to years of yield-seeking speculation. But the assets that will be hit first – and hit hardest in any normalization of yields or risk premiums – are likely to be junk, then equities, then seemingly credit-worthy corporates, with Treasury debt at the tail end of that normalization. But – a Fed-chasing lemming might counter, in the belief that Federal Reserve intervention “works” regardless of investor risk preferences – if the economy softens, doesn’t that ensure that the Fed will come to the rescue by deferring any hike in interest rates? Won’t that in turn drive the financial markets higher? There are two answers to that question. The first, as I noted in The Line Between Rational Speculation and Market Collapse, is a reminder that the Fed did not tighten in 1929, but instead began cutting interest rates on February 11, 1930 – nearly two and a half years before the market bottomed. The Fed cut rates on January 3, 2001 just as a two-year bear market collapse was starting, and kept cutting all the way down. The Fed cut the federal funds rate on September 18, 2007 – several weeks before the top of the market, and kept cutting all the way down. As a result, the second answer to the question above is that it is the wrong question. Our attention should not be absorbed in speculation about what the Fed might or might not do, but should instead attend to measures of investor risk preferences such as market internals and credit spreads. In the event they improve – which we certainly don’t rule out but don’t particularly expect in the near term either – the immediacy of our concerns about downside risk will ease markedly. Depending on the status of other market conditions, we may even observe an opportunity to encourage an outlook more along the lines of “constructive with a safety net.” On the other hand, if we observe a material retreat in valuations followed by an improvement in market action, I expect we could encourage a clearly constructive or even aggressive stance toward the market. So we’ll take our evidence as it comes, with a continued focus on adhering to a historically informed, value-conscious, risk-managed discipline. With respect to risk management, it’s helpful to recognize that it takes two back-to-back 33% losses to experience a 55% loss as the S&P 500 did in 2007-2009. Compounding has very interesting effects over the course of a market cycle. A 50% loss wipes out a 100% gain. A 20% gain in asset X during a 40% loss in asset Y leaves asset X at double the value of asset Y. Passive investment strategies invariably look desirable relative to risk-managed strategies at the peak of a market cycle, because risk-management looks like a mistake in hindsight. Over the course of the complete market cycle – of which we have now experienced an unfinished half – those relative comparisons typically look dramatically different. With median valuations for the average stock higher now than in 2000 on the basis of price/revenue, price/earnings, and enterprise-value to EBITDA; with numerous historically reliable valuation measures more than double their pre-bubble historical norms; and with the S&P 500 now beyond the peak valuations of every market cycle on record (including 1929) except for the final quarters surrounding the 2000 bubble, understand that stocks are no longer an investment but a speculation. There are times that such speculation tends to work out – but those times require risk-seeking preferences among investors, which can be inferred from features of market action that are not in place at present. I expect that these distinctions will serve us greatly over the completion of the present cycle and in those to come. As for the completion of the present cycle, I’ll say this again – the 2000-2002 decline wiped out the entire total return of the S&P 500, in excess of Treasury bill returns – all the way back to May 1996. The 2007-2009 decline wiped out the entire total return of the S&P 500, in excess of Treasury bills – all the way back to June 1995. A shift back toward risk-seeking preferences among investors will not relieve the extreme overvaluation of the equity market, but it would defer our immediate concerns. We may observe constructive opportunities along the way, but we view it as inescapable that the completion of the current market cycle will end in tears for investors who don’t carefully align their investment exposures with their expected spending horizon (see the second half of Hard Won Lessons and the Bird in the Hand for a discussion of these considerations). For now, we maintain a sharply negative outlook toward equities. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed