|

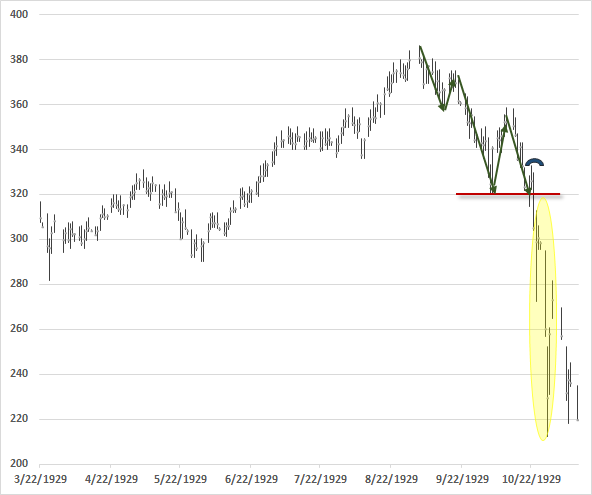

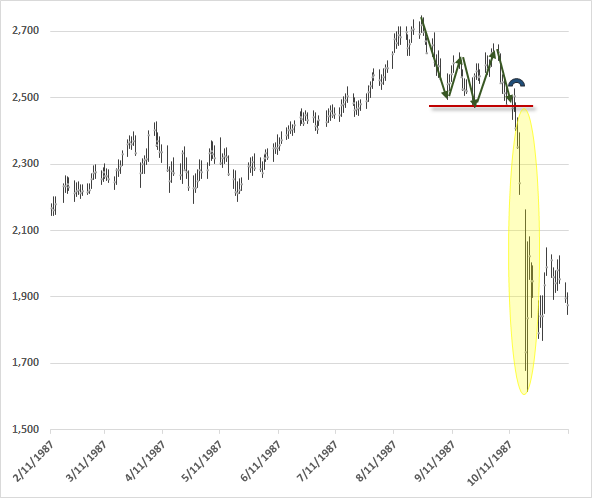

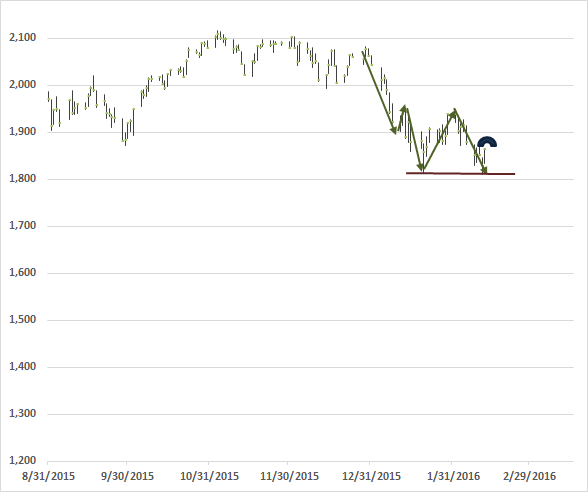

by John Hussman February 15, 2016 Weekly Market Comment Excerpts Given our focus on historically-informed, value-conscious, full-cycle investing, I generally don’t place much attention on short-term technical factors or specific patterns of price action. However, the current setup is one of the few exceptions. In a market return/risk classification that is already the most negative we identify, where a sustained period of speculation has given way increasing risk-aversion, the position of the market relative to very widely identified “support” (about the 1820 level on the S&P 500) is of particular note. Often, well-recognized support levels become places where dip-buyers and swing-traders line up on the buy side, on the assumption that they’ll be rewarded if the market bounces from that support, and that they can quickly cut their losses immediately if the support level is broken. The problem here is that when too many speculators set their stop-loss points at the same level, and valuations are still elevated, there may be neither speculators nor value-conscious investors willing to bid for stock anywhere near those support levels once they break. The resulting gap between eager sellers at a high level and willing buyers at a much lower level is the essential element of market crashes, because every seller requires a buyer. I’ve often observed that market crashes have historically emerged only after a familiar profile of market behavior that features a compressed market retreat of about 14% over 10-12 weeks, a rebound between 1/3 and 2/3 of that decline, a fresh retreat that slightly breaks that initial level of support, a one-day barn-burner advance, and then a collapse as the prior support level is broken. In the 1990’s, I called this pattern the lead-up to “five days of Armageddon” because historically, once rich valuations have been joined with poor market internals (what I used to call “trend uniformity”), the break of a widely-identified support level has often been followed by vertical market losses. The present widely-followed “support” shelf for the S&P 500 is roughly 14% below the 2015 market peak, but most domestic and international indices have already broken corresponding support levels. Given the obscene valuations at the 2015 peak, my impression is that a run-of-the-mill completion of the current market cycle (neither an unusual nor worst-case scenario from a historical perspective) would comprise an additional market decline of roughly 40-50% from present levels. I certainly don’t expect that kind of market loss in one fell swoop. Rather, my immediate concern is that the first leg of this decline could be quite steep. Emphatically, my concern is not simply that the market has retreated by some amount to a widely-identified support level. The issue is the context of rich valuations and poor market internals in which that market weakness has emerged, because when a widely- identified support level gives way at rich valuations, in an environment where poor market internals convey a shift toward risk-aversion among investors, the break can behave as a common trigger for concerted attempts to exit. Though the 1929 and 1987 crashes are the most salient instances, there are numerous less memorable examples across history. As I observed in my June 6, 2002 comment: “I have chosen to call this particular climate a Warning with a capital ‘W’ because every historical market crash of note is found within this one set of conditions. Those conditions are: extremely unfavorable valuations and poor trend uniformity. At present, the market is displaying the same set of characteristics as it did just prior to past market crashes. In both 1929 and 1987, the market crash began about 55 trading sessions after the peak. During those sessions, the market traced out a characteristic pattern of declining peaks and troughs, with a one-day rally just after the third trough (roughly 14% down from the peak), and then ‘five days of Armageddon.’ This is exactly the pattern that the S&P has traced since its late-March peak.” The market followed with a 24% plunge over the following 6 weeks (and an even greater loss on an intra-day basis). It took more than 5 days, but then, the S&P 500 was already down substantially from its 2000 extreme even before that plunge. Prior to the mid-1990’s, the most common “reference” index of investors was the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Presently, the most broadly followed index is the S&P 500 Index. The following charts show the general pattern I’ve described, along with the 1929 and 1987 instances. Now, perhaps the rally since Friday is instead a “successful retest” of prior support. Given that leading economic data, coupled with poor market internals, continue to indicate an imminent U.S. recession, I tend to doubt that possibility, but we’ll take the evidence as it arrives. Despite elevated valuations and deteriorating economic conditions in the U.S. and elsewhere, our immediate downside concerns would ease considerably in the event market internals were to clearly improve on our measures. Here and now, investors should ensure that their market exposures and investment horizons would allow them to tolerate a potential 40-50% market loss over the completion of this market cycle without abandoning their discipline.

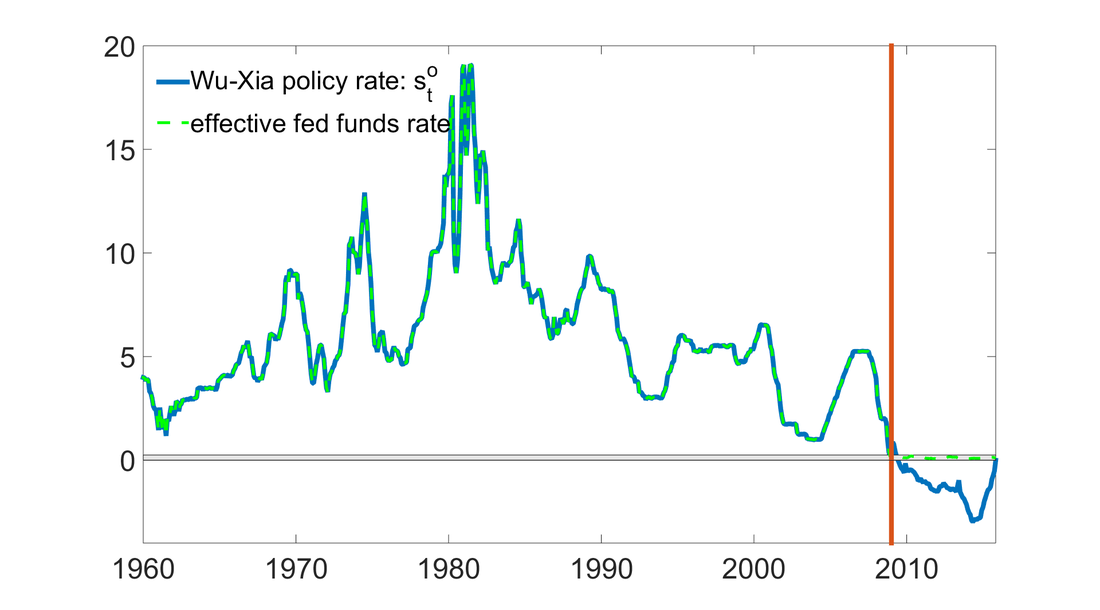

Meanwhile, remember that investors, in aggregate, cannot exit the stock market, or any other market for that matter. Every security that is issued, including base money created by the Federal Reserve, must be held by some investor, at every point in time, in precisely the form it was issued, until that security is retired. The only question is how eager buyers are, relative to sellers. Prices don’t advance because money goes “into” stocks. Every dollar that a stock buyer brings into the market goes right back out in the hands of a seller. No, prices advance because buyers are more eager than sellers. Prices decline because sellers are more eager than buyers. My concern is that support for an increasingly risk-averse market now rests on the fragile resolve of dip-buying speculators primed to cut-and-run at exactly the same nearby support level, beyond which stands a rather shallow pool of powder-dry, value-conscious potential buyers who remain unwilling to commit that powder anywhere near current levels, in a risk-averse market where further central bank intervention is likely to be futile. by John Hussman February 8, 2016 Weekly Market Comment Excerpts Though central bankers and talking heads on television speak about monetary policy as if it has a large and predictable impact on the real economy, decades of evidence underscore a weak and unreliable cause-and-effect relationship between the policy tools of the Fed and the targets (inflation, unemployment) that the Fed hopes to affect. One of the difficulties in evaluating the impact of monetary policy in recent years is that one can’t observe the relative aggressiveness of monetary policy using interest rates, once they hit zero. On that front, economists Cynthia Wu and Fan Dora Xia recently described a clever method to infer a “shadow” federal funds rate based on observable variables (see this University of Chicago article for a good discussion, and the original paper if you’re one of the five geeks who enjoy Kalman filtering, principal components analysis, and vector autoregression as much as I do). The chart below shows the Wu-Xia shadow rate versus the actual federal funds rate. Notably, the Fed doesn’t actually “control” the shadow rate directly, as it does when the Fed Funds rate is above zero. Rather, the shadow rate is statistically inferred using factors such as industrial production, the consumer price index, capacity utilization, the unemployment rate, housing starts, as well as forward interest rates and previously inferred shadow rates.

While it’s very useful to have an estimate of what the “effective” Fed Funds rate might look like at any point in time, be careful not to misinterpret what the shadow rate measures. Again, once interest rates hit zero, the Wu-Xia shadow rate stops being a measure of something that is directly controlled by the Fed. Rather, it measures the possibly negative “shadow” interest rate that would be consistent with the behavior of other observable economic variables. Like the rate of inflation, it’s not at all clear that the Fed can actively manage a negative shadow federal funds rate in a reliably predictable way. In any event, what’s striking from Wu and Xia’s paper is how feeble the estimated impact of QE has been on the real economy. Using vector autoregressions to estimate the trajectory of the economy under various monetary policy assumptions, Wu and Xia observe: “In the absence of expansionary monetary policy, in December 2013, the unemployment rate would be 0.13% higher... the industrial production index would have been 101.0 rather than 101.8... housing starts would be 11,000 lower (988,000 vs. 999,000).” Notably, the Wu-Xia plots of observed and counterfactual economic variables show the same result that we find in our own work: most of the progressive improvement in industrial production, capacity utilization, unemployment, and other economic variables since 2009 would have emerged regardless of activist Fed policy (see Extremes in Every Pendulum). We estimate that this also holds for the improvement in these variables since Wu and Xia's paper was published. Put simply, the Federal Reserve has created the third speculative bubble in 15 years in return for real economic improvements that amount to literally a fraction of 1% from where we would otherwise have been. It’s slightly amusing to hear alarm from some corners that the Wu-Xia rate has increased toward zero - as if the impact of this “tightening” on the real economy is something to be feared. That fear might be valid if there was a strong effect size linking changes in the shadow rate to changes in the real economy. But as Wu and Xia’s own work demonstrates, there is not. The entire global economy seems condemned to repeatedly suffer from deranged central bankers that wholly disregard the weak effect size of monetary policy on policy targets like employment and inflation, and equally disregard their responsibility for the disruptive economic collapses that have followed on the heels of Fed-induced yield-seeking speculation. In short, what we should fear is not the slight impact of recent policy normalizations, but the violent, delayed, yet inevitable consequences of years of speculative distortions that are already fully baked in the cake. What we should fear are the Fed’s repeated and deranged attempts to achieve weak effects on the real economy, at the cost of speculative distortions that exact ten times the damage when they unwind. What we should fear is more of the same Fed recklessness that encouraged a yield-seeking bubble in mortgage debt, enabling a housing bubble that collapsed to create the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. What we should fear is Fed policy that has encouraged a yield-seeking bubble in equities, debt-financed stock repurchases, and covenant-lite junk debt; that has carried capitalization-weighted valuations to the second greatest extreme in history other than the 2000 peak, and median equity valuations to the highest level ever recorded. That’s exactly what the Fed has done in recent years, and the cost of that unwinding is still ahead. by Guy Haselmann

Feburay 18, 2016 Scotiabank A well-known central banker once said to me, “if you don’t have a Plan B, then you don’t have a plan”. When he spoke those words over a year ago, he was referring to the Fed’s lack of an exit strategy from zero rates and its QE-swollen balance sheet. He was telling me that the Fed was so focused on bettering ‘today’ through aggressive stimulus that it could not worry about ‘tomorrow’. He speculated that central banks were “terrified of looking as if they were doing too little”. Part of the Fed’s aggressiveness entailed waiting as long as possible to initiate its first hike. However, many believe that the Fed waited much too long, and in doing so missed the ideal window of opportunity to hike (for the first time in almost nine years). Some would even characterize Twist, QE2 and/or QE3 as unnecessary, labeling it monetary over-reach and the underlying source of the violent market behavior observed since the hike in interest rates. It is likely that a non-linear direct correlation has existed between the length of time the Fed maintained its extreme accommodation and the market’s reaction at the point of rate ‘lift-off’. If this is true, then financial risk assets would have been even more adversely affected if the Fed had waited longer to hike; alternatively, markets would have had a lesser reaction if the Fed had hiked back in 2013/14. This formula likely became even more precise the further nominal GDP underperformed rosy forecasts. Paradoxically, the quick and sharp declines in equity and credit markets have caused many pundits to allege the opposite point of view - that the Fed made a ‘mistake’ by hiking rates in December. It is counter-factual to know for sure, but I maintain that the market reaction would have likely been much less severe had it come earlier, and much more severe had the Fed delayed the inevitable even further. Therefore, if there was a ‘mistake’, it was hiking too late, rather than hiking in December. There is never a “good time” to hike rates (reduction ad absurdum) It is easy to play ‘armchair quarterback’, but few would disagree that ‘good’ policy leads to good outcomes. By waiting so long to shift gears, debt levels increased further, global and US economic growth waned, China and Japan stumbled, and geo-political tensions increased. One thing seems clear, the Fed’s timing became ‘less good’. Some of you may be thinking that the factors just listed would suggest that no hikes would have been best. I disagree. Monetary policy has been unfairly called upon to fix all which ails economies and financial markets. There has to be some tipping point where too much monetary stimulus – via QE or negative rates – ensures negative long-term benefits and great risks to financial stability. Where exactly is this point? Are we there yet? The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) warns against asymmetric monetary policy’s ‘propensity for hugely damaging financial booms and busts’. The BIS believes such policy entrenches financial instability leading to chronic economic weakness, and ruptures the open global economic order (translation: leads to currency wars and protectionism). Markets have developed an unhealthy dependency on central banks to provide ever-greater stimulus with each decline in financial market prices or ebb in economic activity. A highly-combustible paradigm exists when risk assets perform better as economic performance wanes (like today), simply because of the expectations of further central bank support. Current solutions to economic woes reside with politicians not central banks. The only hope of avoiding a severe market downturn going forward is to rebalance the policy mix. Great changes are required in terms of the tax code, health care costs, better property right protections, regulation, entitlements, global trade, and cooperation on international currency policies (to name a few). Over-active monetary policy has been enabling fiscal inaction. Many of these issues are the root causes of economic shortcomings. Without better understanding, clarity, and visibility on these factors, ultra-accommodative monetary policy will remain ineffective. Maximum effectiveness can only result from monetary, fiscal and regulatory policies working together. Yellen’s testimony last week exposed great political tensions. Ironically, both parties, who typically agree on little, were united in their criticism of Fed policy. It was troubling that they dislike both past policies, as well as, all of the Fed’s current options. In other words, they hate higher rates as IOER is, as they called it, “a taxpayer subsidy paid to banks”, but they also criticized the Fed’s QE and zero rate policies. They also displayed great concern for the possibility of negative rates. I believe that market pundits arguing for easier money (or negative rates) do not fully understand the long-run unintended consequences to markets and economies from extreme and long periods of unconventional monetary policy. Market turbulence today is a warning sign. Today, there are almost $7 trillion of sovereign bonds with negative yields. The countries where negative yields are official policy account for almost 25% of global GDP. After Japan experimented with negative rates the Nikkei lost over 15% in two weeks and the Yen unexpectedly appreciated by 7%. Banking shares in the EU, and Japan fell by over 20%. Market angst might be a sign that policymakers are underestimating the economic risks. Unfortunately, central bank policymakers all possess a deep-seeded belief that ‘expanding the money base will lead to inflation’. Many of them believe this, because as they state, ‘that is what happened in the past’. The world today is a vastly different place than in past cycles. The market reaction to the BoJ move is a waving red flag, a warning sign. Central bankers need to realize that there could be significant mis-measurement errors which partially explain their poor forecasts in recent years: populations in developed-world economies are far older; economies and corporations are much more indebted; world economies are more globalized, and; technology has continued to improve at a rapid rate. Old rules cannot be applied well. History might look back on this period as a great intellectual failure for not properly understanding these dynamics. The Fed should spend more of its intellectual power trying to understand why its policy actions have not had the desired or expected result. Draghi gave us an initial hint this week in this regard when he said before EU Parliament that the ECB will be studying Europe’s monetary transition mechanisms. In the meantime, central banks are increasing or maintaining massive accommodation, while seemingly disregarding the risks. As many have written recently, ‘Einstein’s definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result’. Let’s hope that reaction to the BoJ’s experiment into negative rate territory serves as an adequate warning to reassess. Global economic data has been terrible this week. The counter-intuitive short-covering rally in risk assets has provided another opportunity to fade the move. Long-Treasuries remain the most attractive and safest place for portfolios to hide while market turbulence continues and central banks recede from what is shaping up to be counter-productive actions. If the Fed ever moves to negative rates (which I doubt barring a catastrophe), than its ability to conduct effective policy changes will diminish. This is the basis for the increasing number of articles about the elimination of paper currency as a means for it to regain control. For investors, this would be their gold-moment. Under this scenario, it is not unthinkable for gold to rise to $4000 per ounce (to pick a level out of thin air). by Stephen Roach - Stephen S. Roach, former Chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia and the firm's chief economist, is a senior fellow at Yale University's Jackson Institute of Global Affairs and a senior lecturer at Yale's School of Management. He is the author of Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China.

February 18, 2016 Project Syndicate NEW HAVEN – In what could well be a final act of desperation, central banks are abdicating effective control of the economies they have been entrusted to manage. First came zero interest rates, then quantitative easing, and now negative interest rates – one futile attempt begetting another. Just as the first two gambits failed to gain meaningful economic traction in chronically weak recoveries, the shift to negative rates will only compound the risks of financial instability and set the stage for the next crisis. The adoption of negative interest rates – initially launched in Europe in 2014 and now embraced in Japan – represents a major turning point for central banking. Previously, emphasis had been placed on boosting aggregate demand – primarily by lowering the cost of borrowing, but also by spurring wealth effects from appreciating financial assets. But now, by imposing penalties on excess reserves left on deposit with central banks, negative interest rates drive stimulus through the supply side of the credit equation – in effect, urging banks to make new loans regardless of the demand for such funds. This misses the essence of what is ailing a post-crisis world. As Nomura economist Richard Koo has argued about Japan, the focus should be on the demand side of crisis-battered economies, where growth is impaired by a debt-rejection syndrome that invariably takes hold in the aftermath of a “balance sheet recession.” Such impairment is global in scope. It’s not just Japan, where the purportedly powerful impetus of Abenomics has failed to dislodge a struggling economy from 24 years of 0.8% inflation-adjusted GDP growth. It’s also the US, where consumer demand – the epicenter of America’s Great Recession – remains stuck in an eight-year quagmire of just 1.5% average real growth. Even worse is the eurozone, where real GDP growth has averaged just 0.1% over the 2008-2015 period. All of this speaks to the impotence of central banks to jump-start aggregate demand in balance-sheet-constrained economies that have fallen into 1930s-style “liquidity traps.” As Paul Krugman noted nearly 20 years ago, Japan exemplifies the modern-day incarnation of this dilemma. When its equity and property bubbles burst in the early 1990s, the keiretsu system – “main banks” and their tightly connected nonbank corporates – imploded under the deadweight of excess leverage. But the same was true for over-extended, saving-short American consumers – to say nothing of a eurozone that was basically a levered play on overly-inflated growth expectations in its peripheral economies – Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain. In all of these cases, balance-sheet repair preempted a resurgence of aggregate demand, and monetary stimulus was largely ineffective in sparking classic cyclical rebounds. This could be the greatest failure of modern central banking. Yet denial runs deep. Former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan’s “mission accomplished” speech in early 2004 is an important case in point. Greenspan took credit for using super-easy monetary policy to clean up the mess after the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, while insisting that the Fed should feel vindicated for not leaning against the speculative madness of the late 1990s. That left Greenspan’s successor on a very slippery slope. Quickly out of ammunition when the Great Crisis hit in late 2008, former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke embraced the new miracle drug of quantitative easing – a powerful antidote for markets in distress but ultimately an ineffective tool to plug the hole in consumer balance sheets and spark meaningful revival in aggregate demand. European Central Bank President Mario Draghi’s famous 2012 promise to do “whatever it takes” to defend the euro took the ECB down the same path – first zero interest rates, then quantitative easing, now negative policy rates. Similarly, Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda insists that so-called QQE (quantitative and qualitative easing) has ended a corrosive deflation – even though he has now opted for negative rates and pushed back the BOJ’s 2% inflation target to mid-2017. It remains to be seen whether the Fed will resist the temptation of negative interest rates. But most major central banks are clinging to the false belief that there is no difference between the efficacy of the conventional tactics of monetary policy – driven by adjustments in policy rates above the zero bound – and unconventional tools such as quantitative easing and negative interest rates. Therein lies the problem. In the era of conventional monetary policy, transmission channels were largely confined to borrowing costs and their associated impacts on credit-sensitive sectors of real economies, such as homebuilding, motor vehicles, and business capital spending. As those sectors rose and fell in response to shifts in benchmark interest rates, repercussions throughout the system (so-called multiplier effects) were often reinforced by real and psychological gains in asset markets (wealth effects). That was then. In the brave new era of unconventional monetary policy, the transmission channel runs mainly through wealth effects from asset markets. Two serious complications have arisen from this approach. The first is that central banks have ignored the risks of financial instability. Drawing false comfort from low inflation, overly accommodative monetary policies have led to massive bubbles in asset and credit markets, resulting in major distortions in real economies. When the bubbles burst and pushed unbalanced economies into balance-sheet recessions, inflation-targeting central banks were already low on ammunition – taking them quickly into the murky realm of zero policy rates and the liquidity injections of quantitative easing. Second, politicians, drawing false comfort from frothy asset markets, were less inclined to opt for fiscal stimulus – effectively closing off the only realistic escape route from a liquidity trap. Lacking fiscal stimulus, central bankers keep upping the ante by injecting more liquidity into bubble-prone financial markets – failing to recognize that they are doing nothing more than “pushing on a string” as they did in the 1930s. The shift to negative interest rates is all the more problematic. Given persistent sluggish aggregate demand worldwide, a new set of risks is introduced by penalizing banks for not making new loans. This is the functional equivalent of promoting another surge of “zombie lending” – the uneconomic loans made to insolvent Japanese borrowers in the 1990s. Central banking, having lost its way, is in crisis. Can the world economy be far behind? The Telegraph

by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard 11 February, 2016 The Japanese yen has become the lightning rod of extreme stress in the global financial system, rocketing this week in violent moves that threaten to plunge Japan back into deep deflation and overwhelm the experiment of "Abenomics". The currency has appreciated by 9pc against the US dollar since the Bank of Japan (BoJ) cut interest rates below zero for the first time ever at the end of January, entirely defeating the purpose. The yen broke through ¥111 in early trading on Thursday as safe-haven flows poured into the country and vast positions were unwound on the global derivative markets. This wiped out all the depreciation effects of the country’s "weak yen" policy over the past 15 months. The Nikkei index of stocks in Tokyo has fallen 22pc since early December. The drastic developments have been nothing less than a disaster for Governor Haruhiko Kuroda who pushed through negative rates against strong protests by half the bank’s voting members. The chief motive for the move was counter deflation by weakening the currency. “This is a reverse policy shock. We are reaching the limits of quantitative easing as we know it,” said David Bloom, currency chief at HSBC. “Countries are losing their ability to drive down their currencies.” The Bank of Japan bought vast amounts of US Treasuries in 2003 in direct intervention to devalue the yen but any such action in today’s neuralgic markets would trigger accusations of currency warfare. It would violate a solemn accord by G20 leaders prohibiting the use of QE for exchange rate purposes. Mr Bloom said there is almost nothing the Bank of Japan can do to stop inflows of money in any case. “The Swiss spent €150bn over four months to hold down the franc and achieved nothing in a market that is 14 times smaller,” he said. Japan is already in the grip of deflation. Producer prices fell 3.1pc in January. The economy almost certainly contracted in the fourth quarter. “Japan’s economy is in a very dire situation,” said Yoshiki Shinke from Dai-ichi Life. The surging yen tightens the noose further, calling into question the whole strategy of premier Shinzo Abe, the strongman who swept into office three yeas ago with bold plans to break the country’s deflationary psychology once and for all. “This could go down in the history books as the death of Abenomics,” said Neil Mellor from BNY Mellon. “Abe cannot stand aside and let the project die like this. But negative interest rates have backfired and hurt the banks, so what are they going to do next?” he said. Abenomics never lived up to its billing, although QE did succeed in driving the yen to its lowest level in trade-weighted terms since the early 1980s. It also led to windfall profits for Japanese companies, but little was put to use or passed through in higher wages. The crucial "third arrow" of Thatcherite reform hardly flew at all. A premature rise in the consumption tax tipped the economy back into recession before it had reached "escape velocity". The yen is closely-watched by traders as a global stress indicator. It has spiked wildly at the onset of each global upheaval over the past three decades, including the East Asian crisis in 1998 and the Lehman crash in 2008. This odd dynamic occurs because Japan is the world’s biggest net creditor by far, with net assets of $3.5 trillion overseas equal to 72pc of GDP, a ratio comparable to that of Switzerland and Norway but on a vastly greater scale. The Japanese tend to bring their money home whenever they lose confidence in global markets, typically closing "carry trade" positions en masse and sparking an explosive collective impact. Hans Redeker, head of currencies at Morgan Stanley, said Japanese funds have record levels of “unhedged” assets in the US that are suddenly at risk as the US Federal Reserve retreats from monetary tightening and yields plummet on US Treasuries. “Value at risk is coming into play and this is forcing funds to cut back,” he said. The 10-year yield on US Treasuries has plummeted to 1.57pc from 2.31pc six weeks ago, with similar moves across the yield curve. This has obliterated the crowded "long US" trade so popular in Japan. The proverbial “Mrs Watanabe” – Japan’s day-trading housewives and grannies – are famed for playing the global markets with too much leverage and gusto. The yen syndrome has been amplified by the effects of QE. The Bank of Japan has been buying $70bn of bonds each month, effectively monetising the entire budget deficit. It is has gobbled up 33pc of the country’s $9.3 trillion public debt. This has pushed Japanese banks, life insurers and Japan’s $1.2 trillion pension fund (GPIF) out of government bonds and into foreign investments, a deliberate strategy to force down the currency. The snag is that this tightens the elastic. It can snap back ferociously, as we have seen this week. Kenji Abe from Bank of America said the BoJ could cut rates to -1pc, a move that would drive the 10-year bond yield from zero to -0.8pc under the bank’s model. This would, in theory, lift corporate earnings by 5pc and set off a stock market rally. Kazumasa Iwata, the former deputy governor of the BoJ, said rates could drop to -2pc, uncharted territory even in the current topsy-turvy world. There comes a point when even large investors switch to cash instruments. It is unclear what more can be achieved by tinkering with interest rates. The Bank of Japan might gain more traction by expanding its purchases from real estate "REITS" and exchange-traded funds to a broader range of securities, injecting money into the veins of the stock market. Ultimately, the BoJ and its peers in Europe and the US may have to resort to variants of "helicopter money" and the blanket funding of New Deal programmes to counter the next recession. None is yet ready to cross the Rubicon, and the markets know it. The Telegraph

by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard February 9, 2016 Credit stress in the European banking system has suddenly turned virulent and begun spreading to Italian, Spanish and Portuguese government debt, reviving fears of the sovereign "doom-loop" that ravaged the region four years ago. “People are scared. This is very close to a potentially self-fulfilling credit crisis,” said Antonio Guglielmi, head of European banking research at Italy's Mediobanca. “We have a major dislocation in the credit markets. Liquidity is totally drained and it is very difficult to exit trades. You can’t find a buyer,” he said. The perverse result is that investors are "shorting" the equity of bank stocks in order to hedge their positions, making matters worse. Marc Ostwald, a credit expert at ADM, said the ominous new development is that bank stress has suddenly begun to drive up yields in the former crisis states of southern Europe. “The doom-loop is rearing its ugly head again,” he said, referring to the vicious cycle in 2011 and 2012 when eurozone banks and states engulfed in each other in a destructive vortex. It comes just as sovereign wealth funds from the commodity bloc and emerging markets are forced to liquidate foreign assets on a grand scale, either to defend their currencies or to cover spending crises at home. Mr Ostwald said the Bank of Japan’s failure to gain any traction by cutting interest rates below zero last month was the trigger for the latest crisis, undermining faith in the magic of global central banks. “That was unquestionably the straw that broke the camel’s back. It has created havoc,” he said. Yield spreads on Italian and Spanish 10-year bonds have jumped to almost 150 basis points over German Bunds, up from 90 last year. Portuguese spreads have surged to 235 as the country’s Left-wing government clashes with Brussels on austerity policies. While these levels are low by crisis standards, they are rising even though the European Central Bank is buying the debt of these countries in large volumes under quantitative easing. The yield spike is a foretaste of what could happen if and when the ECB ever steps back. Mr Guglielmi said a key cause of the latest credit seizure is the imposition of a tough new “bail-in” regime for eurozone bank bonds without the crucial elements of an EMU banking union needed make it viable. “The markets are taking their revenge. They have been over-regulated and now are demanding a sacrificial lamb from the politicians,” he said. Mr Guglielmi said there is a gnawing fear among global investors that these draconian "bail-ins" may be crystallised as European banks grapple with €1 trillion of non-performing loans. Declared bad debts make up 6.4pc of total loans, compared with 3pc in the US and 2.8pc in the UK. The bail-in rules were first imposed in Cyprus after the island's debt crisis, stripping European bank debt of its hallowed status as a pillar of financial stability, and of its implicit guarantee by states. The regime came into force for the whole currency bloc in January. Both senior and junior debt must now face wipeout before taxpayers have to contribute money. While this makes sense on one level, the eurozone banking structure is now dangerously deformed. Individual eurozone states cannot easily recapitalize their own banking systems because that breaches EU state-aid rules, but there is no functioning European body to replace them. “The root cause of this debacle is the way the eurozone is designed. We don’t have a mutualisation of the risks. That is why this is escalating,” said Mr Guglielmi. Europe’s leaders agreed in June 2012 to break the “vicious circle between banks and sovereigns” but Germany, Holland, Austria and Finland later walked away from this crucial pledge. The chief cost of rescuing banks still falls on the shoulders of each sovereign state. The Sword of Damocles still hangs over the weakest countries. Peter Schaffrik, from RBC Capital Markets, said there is a nagging concern among investors that the ECB is running low on ammunition. It cannot usefully cut interest rates any deeper into negative territory since the current level of -0.3pc is already burning up the “net interest margin’ of lenders and eroding bank profits. “How much further can the ECB go before it becomes outright harmful?” he asked. A string of dire results from banks have set off a firesale on "Cocos", bonds that allow lenders to miss a coupon payment and switch the debt to equity. A Unicredit issue of €1bn of Coco bonds has crashed to 72 cents on the euro. The iTraxx Senior Financial index measuring default risk for bank debt in Europe soared to 137 on Tuesday, from 68 as recently as early December. Mr Guglielmi said the mood is starting to feel like the panic in the summer of 2012, just before Mario Draghi vowed to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro – a shift made possible when Berlin lifted its veto on emergency action to backstop Italian and Spanish bonds. Mr Draghi is running out of tricks for an encore but there is still scope for "QE2" at the next ECB meeting in March, if he can secure German acquiescence. He could legally purchase parastatal bonds such as those of Italy’s power group ENEL or Infraestucturas de Portugal, or purchase Italian bad debt packaged as asset-backed securities. “He can buy Italian subprime. That is the low-hanging fruit,” said Mr Guglielmi. “We all know that QE2 is not really going to work but the feeling in the market is ‘I’m a smoker, I know it kills me, but so long as I can get cigarettes, I’m happy,'” he said. Project Syndicate

by Nouriel Roubini February 4, 2016 NEW YORK – Since the beginning of the year, the world economy has faced a new bout of severe financial market volatility, marked by sharply falling prices for equities and other risky assets. A variety of factors are at work: concerns about a hard landing for the Chinese economy; worries that growth in the United States is faltering at a time when the Fed has begun raising interest rates; fears of escalating Saudi-Iranian conflict; and signs – most notably plummeting oil and commodity prices – of severe weakness in global demand. And there’s more. The fall in oil prices – together with market illiquidity, the rise in the leverage of US energy firms and that of energy firms and fragile sovereigns in oil-exporting economies – is stoking fears of serious credit events (defaults) and systemic crisis in credit markets. And then there are the seemingly never-ending worries about Europe, with a British exit (Brexit) from the European Union becoming more likely, while populist parties of the right and the left gain ground across the continent. These risks are being magnified by some grim medium-term trends implying pervasive mediocre growth. Indeed, the world economy in 2016 will continue to be characterized by a New Abnormal in terms of output, economic policies, inflation, and the behavior of key asset prices and financial markets. So what, exactly, is it that makes today’s global economy abnormal? First, potential growth in developed and emerging countries has fallen because of the burden of high private and public debts, rapid aging (which implies higher savings and lower investment), and a variety of uncertainties holding back capital spending. Moreover, many technological innovations have not translated into higher productivity growth, the pace of structural reforms remains slow, and protracted cyclical stagnation has eroded the skills base and that of physical capital. Second, actual growth has been anemic and below its potential trend, owing to the painful process of deleveraging underway, first in the US, then in Europe, and now in highly leveraged emerging markets. Third, economic policies – especially monetary policies – have become increasingly unconventional. Indeed, the distinction between monetary and fiscal policy has become increasingly blurred. Ten years ago, who had heard of terms such as ZIRP (zero-interest-rate policy), QE (quantitative easing), CE (credit easing), FG (forward guidance), NDR (negative deposit rates), or UFXInt (unsterilized FX intervention)? No one, because they didn’t exist. But now these unconventional monetary-policy tools are the norm in most advanced economies – and even in some emerging-market ones. And recent actions and signals from the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan reinforce the view that more unconventional policies are to come. Some alleged that these unconventional monetary policies – and the accompanying ballooning of central banks’ balance sheets – were a form of debasement of fiat currencies. The result, they argued, would be runaway inflation (if not hyperinflation), a sharp rise in long-term interest rates, a collapse in the value of the US dollar, a spike in the price of gold and other commodities, and the replacement of debased fiat currencies with cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin. Instead – and this is the fourth aberration – inflation is still too low and falling in advanced economies, despite central banks’ unconventional policies and surging balance sheets. The challenge for central banks is to try to boost inflation, if not avoid outright deflation. At the same time, long-term interest rates have continued to come down in recent years; the value of the dollar has surged; gold and commodity prices have fallen sharply; and bitcoin was the worst performing currency of 2014-2015. The reason ultra-low inflation remains a problem is that the traditional causal link between the money supply and prices has been broken. One reason for this is that banks are hoarding the additional money supply in the form of excess reserves, rather than lending it (in economic terms, the velocity of money has collapsed). Moreover, unemployment rates remain high, giving workers little bargaining power. And a large amount of slack remains in many countries’ product markets, with large output gaps and low pricing power for firms (an excess-capacity problem exacerbated by Chinese overinvestment). And now, following a massive decline in housing prices in countries that experienced a boom and bust, oil, energy and other commodity prices have collapsed. Call this the fifth anomaly – the result of China’s slowdown, the surge in supplies of energy and industrial metals (following successful exploration and overinvestment in new capacity), and the strong dollar, which weakens commodity prices. The recent market turmoil has started the deflation of the global asset bubble wrought by QE, though the expansion of unconventional monetary policies may feed it for a while longer. The real economy in most advanced and emerging economies is seriously ill, and yet, until recently, financial markets soared to greater highs, supported by central banks’ additional easing. The question is how long Wall Street and Main Street can diverge. In fact, this divergence is one aspect of the final abnormality. The other is that financial markets haven’t reacted very much, at least so far, to growing geopolitical risks either, including those stemming from the Middle East, Europe’s identity crisis, rising tensions in Asia, and the lingering risks of a more aggressive Russia. Again, how long can this state of affairs – in which markets not only ignore the real economy, but also discount political risk – be sustained? Welcome to the New Abnormal for growth, inflation, monetary policies, and asset prices, and make yourself at home. It looks like we’ll be here for a while. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed