|

by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

The Telegraph 30 October, 2014 Mind the monetary gap as the world's two superpowers turn off the liquidity spigot at the same time. The US Federal Reserve and the People’s Bank of China have both withdrawn from the global bond markets, each for their own entirely different reasons. The combined effect is a shock of sorts for the international financial system. The Fed’s message on Wednesday night was hawkish. It did not invoke the excuse of a stronger dollar or global market jitters to extened bond purchases. It no longer sees “significant” constraints to the labour market. Instead it spoke of “solid job gains” and a “gradual diminishing” of under-employment. This a tightening shift, and seen as such by the markets. The euro dropped 1.5 cents against a resurgent dollar within minutes of the release, falling back below $1.26. Rate rises are on track for mid-2015 after all. The Fed is no longer printing any more money to buy Treasuries, and therefore is not injecting further dollars into an interlinked global system that has racked up $7 trillion of cross-border bank debt in dollars and a further $2 trillion in emerging market bonds. The stock of QE remains the same. The flow has changed. Flow matters. The Fed has ended QE3 more gently than QE1 or QE2. This helps but it may also have given people a false sense of security. The hard fact is that the Fed has tapered net stimulus from $85bn a month to zero since the start of the year. The FOMC tried to soften the blow in its statement with pledges to keep interest rates low for a very long time. This assurance has value only if you think QE works by holding down interest rates, as the Yellen Fed professes to believe. It cuts no ice if you are a classical monetarist and think that QE works its magic through the quantity of money effect, most potently by boosting broad M3/M4 money through purchases of assets outside the banking system. Pessimists argue that the world economy is so weak that it needs a minimum of $85bn a month of Fed money creation (not to be confused with zero interest rates) just to avoid stalling again. Or put another way, there is nagging worry that tapering itself may amount to an entire tightening cycle, equivalent to a series of rate rises in the old days. If they are right, rates may never in fact rise above zero in the US or the G10 states before the global economy slides into the next downturn. It is no great mystery why the world is caught in this "liquidity trap", or "secular stagnation" if you prefer. Fixed capital investment in China is still running at $5 trillion a year, and still overloading the world with excess capacity in everything from solar panels to steel and ships, even after Xi Jinping’s Third Plenum reforms. Europe has been starving the world of demand by tightening fiscal policy into a depression, running a $400bn current account surplus that is now big enough to distort the global system as a whole. George Saravelos, at Deutsche Bank, dubs it the "Euroglut", the largest surplus in the history of financial markets. The global savings rate has risen to a fresh record of 25.5pc of GDP, the flipside of chronic under-consumption. Of course, it is not the job of the Fed to run monetary policy for the world, and that is the new problem facing QE-addicted investors. The US economy is growing briskly at a 3pc rate. It can arguably handle monetary tightening, at least for now. New home building is up 17.8pc over the past year. The Case-Shiller 20-City index of house prices is up 22pc since early 2012. Unemployment has tumbled to 5.9pc. Lay-offs have dropped to a 14-year low. We are entering a new phase of the monetary cycle where the US is strong (relatively) and the world is weak (relatively). The Fed has switched from a being the friend of global asset prices, to being neutral at best, with a strong hint of menace. It is a very odd environment. The US Treasury market is pricing in near-depression conditions. Five-year inflation expectations have suddenly collapsed. You could say it is remarkable that the Fed should be withdrawing any stimulus at all in such circumstances. Janet Yellen has to navigate a perilous course between the Scylla of deflation and the Charybdis of corrosive asset booms, just the like the Riksbank this week, or indeed the Bank of Canada, or the Bank of England. Yet the precipitous slide in commodities since June may be a warning sign that stress is building. There are echoes of 1928, when commodity prices buckled even as the boom on Wall Street was still gathering pace, and as the credit bubble in Weimar Germany was still gathering towards a crescendo. Fed hawks, led by Benjamin Strong, chose to ignore the deflation risk, instead raising rates to teach “speculators” a lesson. The move set off a global chain reaction. Mrs Yellen is unlikely to repeat that error, but there are many pushing her to do so, and since she is not a monetarist, she may have misjudged the quantity effects of tapering. Note that the growth rate of Divisia M4 – a broad measure of the money supply tracked by the Center for Financial Stability - has dropped to 2pc from 6.2pc in early 2013. The Fed pivot comes at a delicate moment because China’s (PBOC) is at the same time winding down stimulus, trying to tame China’s $25 trillion credit monster before it is too late. The central bank has not yet blinked - beyond minor short-term liquidity shots - even though bad loans are rising fast at the big state banks. China became a net seller of global bonds in the third quarter (even adjusting for currency effects). It was buying $35bn a month earlier this year. The move was well-flagged in advance. Premier Li Keqiang said in May that excess foreign reserves had become a "burden" and were making it impossible for China to run a sovereign monetary policy. The policy shift automatically entails monetary tightening – vis-à-vis the status quo ante – unless China acts to sterilise the effects. It has not done so. We have seen a sudden stop in China’s “proxy QE”. Brazil, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand all cut their foreign reserves in the third quarter. Korea slashed net purchases from $25bn to $9bn, and India from $43bn to $12bn. Russia is now burning through its reserves to defend the rouble. Others oil states will have to do the same to cover their budgets. Net bond stimulus by all the global central banks together has fallen by roughly $125bn a month since the end of last year, an annualised pace of $1.5 trillion. We have seen an abrupt halt to the $10.2 trillion of net reserve accumulation since 2000 that has played such a role in the asset boom of the modern era. That does not automatically mean asset prices will fall, but it removes a powerful tailwind. Hopes that the Europe would pick up the QE baton to keep the asset boom going border on wishful thinking. The European Central Bank’s balance sheet has contracted by almost €150bn due to passive tightening since the Mario Draghi first spoke of buying asset-backed securities in June. There is much chatter from peripheral ECB governors, a talkative lot. Listen instead to Sabine Lautenschläger, Germany’s member of the ECB’s executive board. Her predecessor backed the Draghi rescue plan for Italy and Spain (OMT) in August 2012 against objections from the Bundesbank, and that is what made it possible. I may be wrong, but it strikes me as implausible that the ECB will risk launching QE on a massive scale as long as both German members are opposed. The bank can dabble at the edges, as it is doing now, but a reflation blitz requires German political assent. So what is Dr Lautenschläger saying? "I take a more critical view of some areas of the ECB's unconventional measures. If we talk about large-scale purchase programmes of securitised assets, the so-called ABS plan, or even large-scale sovereign bond purchases - then I take a more critical view, because for me the balance between costs and needs is negative at the moment. Those are measures one uses as a last resort if deflation is visible and that is by no means the case.” Draw your own conclusions. History.com

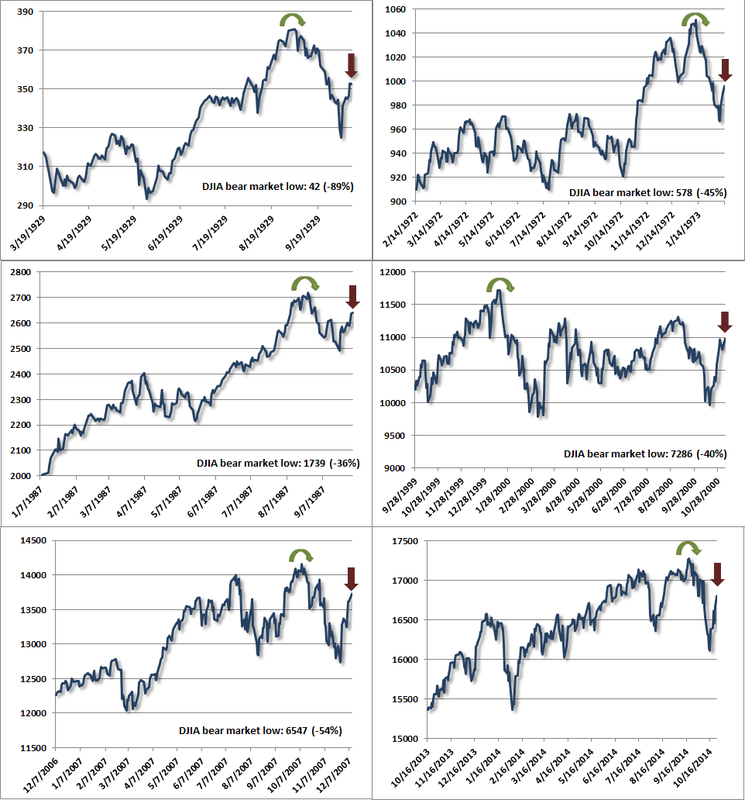

October 29, 2014 On October 29, 1929, Black Tuesday hit Wall Street as investors traded some 16 million shares on the New York Stock Exchange in a single day. Billions of dollars were lost, wiping out thousands of investors. In the aftermath of Black Tuesday, America and the rest of the industrialized world spiraled downward into the Great Depression (1929-39), the deepest and longest-lasting economic downturn in the history of the Western industrialized world up to that time. During the 1920s, the U.S. stock market underwent rapid expansion, reaching its peak in August 1929, after a period of wild speculation. By then, production had already declined and unemployment had risen, leaving stocks in great excess of their real value. Among the other causes of the eventual market collapse were low wages, the proliferation of debt, a struggling agricultural sector and an excess of large bank loans that could not be liquidated. Stock prices began to decline in September and early October 1929, and on October 18 the fall began. Panic set in, and on October 24, Black Thursday, a record 12,894,650 shares were traded. Investment companies and leading bankers attempted to stabilize the market by buying up great blocks of stock, producing a moderate rally on Friday. On Monday, however, the storm broke anew, and the market went into free fall. Black Monday was followed by Black Tuesday (October 29), in which stock prices collapsed completely and 16,410,030 shares were traded on the New York Stock Exchange in a single day. Billions of dollars were lost, wiping out thousands of investors, and stock tickers ran hours behind because the machinery could not handle the tremendous volume of trading. After October 29, 1929, stock prices had nowhere to go but up, so there was considerable recovery during succeeding weeks. Overall, however, prices continued to drop as the United States slumped into the Great Depression, and by 1932 stocks were worth only about 20 percent of their value in the summer of 1929. The stock market crash of 1929 was not the sole cause of the Great Depression, but it did act to accelerate the global economic collapse of which it was also a symptom. By 1933, nearly half of America’s banks had failed, and unemployment was approaching 15 million people, or 30 percent of the workforce. Relief and reform measures enacted by the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) helped lessen the worst effects of the Great Depression; however, the U.S. economy would not fully turn around until after 1939, when World War II (1939-45) revitalized American industry. Weekly Market Comment October 27, 2014 by John P. Hussman, Ph.D. My impression is that we are observing a similar dynamic at present. Though we remain open to the potential for market internals to improve convincingly enough to at least defer our immediate concerns about market risk, we should also be mindful of the sequence common to the 1929, 1972, 1987, 2000 and 2007 episodes: 1) an extreme syndrome of overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions (rich valuations, lopsided bullish sentiment, uncorrected and overextended short-term action); 2) a subtle breakdown in market internals across a broad range of stocks, industries, and security types; 3) an initial “air-pocket” type selloff to an oversold short-term low; 4) a “fast, furious, prone-to-failure” short squeeze to clear the oversold condition; 5) a continued pairing of rich valuations and dispersion in market internals, resulting in a continuation to a crash or a prolonged bear market decline. The panel of charts below shows the Dow Jones Industrial Average in those prior episodes, with the present episode at the lower right. The rounded green arrows identify the bull market peaks in DJIA (or in the 2014 chart, the highest level observed to-date), while the red arrows identify “fast, furious, prone-to-failure” advances that followed the market peak, generally after market internals had already deteriorated. The spikes marked the highest points that the DJIA would see over the remainder of those market cycles, on the way to far deeper bear market lows. The 2000 instance saw an extended period of churning between the January 2000 bull market high in the DJIA and later in the year. The 2000-2002 bear market ultimately asserted itself in earnest once our measures of market internals shifted decidedly negative on September 1, 2000 (see the October 2000 Hussman Investment Research & Insight). In the 2014 chart, the red arrow identifies the rally over the past several sessions. What characterizes the instances below is not simply a decline from a market peak and a subsequent rally, but the sequence from historically extreme overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions (see Exit Strategy) to a deterioration in market internals, an initial "air pocket" decline, and a subsequent short-squeeze that fails to restore market internals to a favorable condition. Of course, the prior episodes shown below are not themselves indicative of what will occur in the present instance, and current conditions might not be resolved in the same way. Still, investors should interpret recent market strength in its full context: we’ve observed a fast, furious advance to clear an oversold “air-pocket” decline – one that emerged from the pairing of rich valuations with a breakdown in market internals. Having cleared that oversold condition, we remain concerned that the pairing of rich valuations and still-injured market internals may reassert itself. Longer term, we continue to view present market conditions as among the most hostile in history, coupling rich valuations with market internals that remain unfavorable on historically reliable measures. So allow for any sort of action in the near term, but recognize that from a full-cycle perspective, we continue to view a 40-50% market loss as having very reasonable plausibility over the completion of this market cycle.

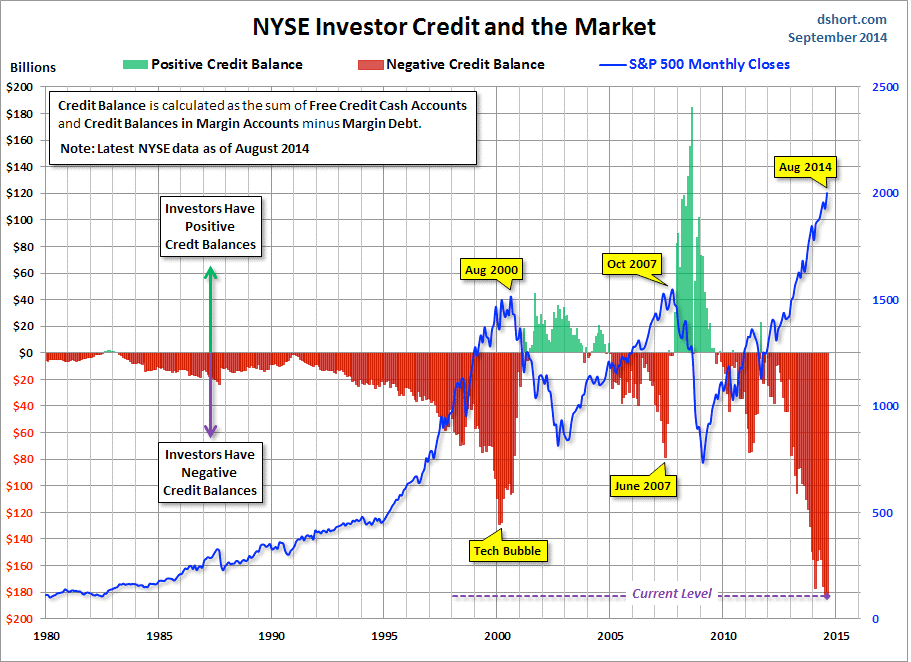

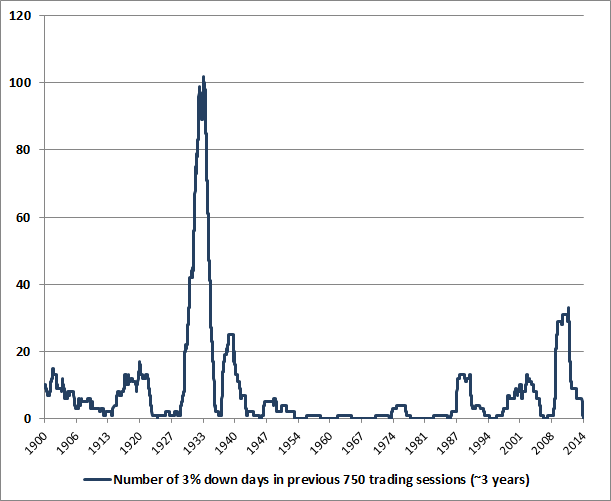

Weekly Market Comment October 20, 2014 by John P. Hussman, Ph.D. Excerpts: Abrupt market losses typically reflect compressed risk premiums that are then joined by a shift toward increased risk aversion by investors. In market cycles across history, we find that the distinction between an overvalued market that continues to become more overvalued, and an overvalued market is vulnerable to a crash, often comes down to a subtle but measurable shift in the preference or aversion of investors toward risk – a shift that we infer from the quality of market action across a wide range of internals. Valuations give us information about the expected long-term compensation that investors can expect in return for accepting market risk. But what creates an immediate danger of air-pockets, free-falls and crashes is a shift toward risk aversion in an environment where risk premiums are inadequate. One of the best measures of investor risk preferences, in our view, is the uniformity or dispersion of market action across a wide variety of stocks, industries, and security types. Once market internals begin breaking down in the face of prior overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions, abrupt and severe market losses have often followed in short order. That’s the narrative of the overvalued 1929, 1973, and 1987 market peaks and the plunges that followed; it’s a dynamic that we warned about in real-time in 2000 and 2007; and it’s one that has emerged in recent weeks (see Ingredients of A Market Crash). Until we observe an improvement in market internals, I suspect that the present instance may be resolved in a similar way. As I’ve frequently noted, the worst market return/risk profiles we identify are associated with an early deterioration in market internals following severely overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions. --- Keep in mind that even terribly hostile market environments do not resolve into uninterrupted declines. Even the 1929 and 1987 crashes began with initial losses of 10-12% that were then punctuated by hard advances that recovered about half of those losses before failing again. The period surrounding the 2000 bubble peak included a series of 10% declines and recoveries. The 2007 top began with a plunge as market internals deteriorated materially (see Market Internals Go Negative) followed by a recovery to a marginal new high in October that failed to restore those internals. One also tends to see increasing day-to-day volatility, and a tendency for large moves to occur in sequence. An interesting feature of the recent air-pocket in stock prices is that many observers characterize the depth of the recent selloff as meaningful. What we’ve seen in recent weeks is very minor in a historical, full-cycle context. The market has not experienced even a single 3% down day in nearly 3 years. The chart below shows the cumulative number of 3% down-days in the Dow Jones Industrial Average over the prior 750 trading sessions, in data over the past century. It’s certainly not an indicator that we would use in isolation, but in given current valuations and the recent deterioration in market internals, we should not be surprised if this absence of large daily losses is short-lived. I mention large down-days for a reason. A market crash comprises of a series of one-day losses that may be large, but are not particularly extraordinary in and of themselves. The problem is that they tend to occur in sequence rather than independently. In the chart above, you’ll notice that the cumulative total of 3%+ down days often spikes nearly vertically from zero, meaning that large down days tend to cluster. We may wish to believe that a 25-30% market plunge has zero probability since we know that the probability of a one-day loss of several percent is quite low, making a whole series of them seemingly impossible. But that view overlooks the tendency of large losses to occur in succession. It also overlooks the tendency for monetary easing to support stocks only when low- or zero-interest risk-free assets are considered inferior holdings in comparison to risky ones.

--- In short, recent weeks have seen a strenuously overbought record high in the S&P 500 featuring the most lopsided bullish sentiment (Investor’s Intelligence) since 1987, coupled with increasing divergence and deterioration across a wide range of market internals, including small-capitalization stocks, junk debt, market breadth, and other measures. With compressed risk premiums now joined by indications of increasing risk aversion, we remain concerned that risk premiums will normalize not gradually but in spikes, as is their historical tendency. By John Mauldin October 13, 2014 You don’t need a weatherman Did you feel the economic weather change this week? The shift was subtle, like fall tippy-toeing in after a pleasant summer to surprise us, but I think we’ll look back and say this was the moment when that last grain of sand fell onto the sandpile, triggering many profound fingers of instability in a pile that has long been close to collapse. This is the grain of sand that sets off those long chains of volatility that have been gathering for the last five years, waiting to surprise us with the suddenness and violence of the avalanche they unleash.

I suppose the analogy sprang to mind as I stepped out onto my balcony this morning. Texas has been experiencing one of the most pleasant summers and incredibly wonderful falls in my memory. One of the conversations that seem to occur regularly among locals who have a few decades under their belts here, is just how truly remarkable the weather has been. So it was a bit of a surprise to step out and realize the air had turned brisk. In retrospect it shouldn’t have fazed me. The air has been turning brisk in Texas at some point in October for the six decades that my memory covers, and for quite a few additional millennia, I suspect. But this week, as I worked through my ever-growing mountain of reading, I felt a similar awareness of a change in the economic climate. Like fall, I knew it was coming. In fact, I’ve been writing about it for years! But just as fall tells us that it’s time to get ready for winter, at least in more northerly climes, the portents of the moment suggest to me that it’s time to make sure our portfolios are ready for the change in season. Sea Change Shakespeare coined the marvelous term sea change in his play The Tempest. Modern-day pundits are liable to apply the word to the relatively minor ebb and flow of events, but Shakespeare meant sea change as a truly transformative event, a metamorphosis of the very nature and substance of a man, by the sea. In this week’s letter we’ll talk about the imminent arrival of a true financial sea change, the harbinger of which was some minor commentary this week about the economic climate. This letter is arriving to you a little later this week, as I had quite some difficulty writing it, because, while the signal event is rather easy to discuss, the follow-on consequences are myriad and require more in-depth analysis than I’ve been able to bring to them on short notice. As I wrestled with what to write, I finally came to realize that this sea change is going to take multiple letters to properly describe. In fact, it might eventually take a book. So, in a departure from my normal writing style, I am going to offer you a chapter-by-chapter outline for a book. As with all book outlines, it will be simply full of bones but without much meat on them, let alone dressed up with skin and clothing. I will probably even connect the bones in the wrong order and have to go back later and replace a leg bone with a rib, but that is what outlines are for. There is clearly enough content suggested by this outline to carry us through the next several months; and given the importance of the subject, I expect to explore it fully with you. Whether it actually becomes a book, I cannot yet say. I should note that much of what follows has grown out of in-depth conversations with my associate Worth Wray and our mutual friends. We’ve become convinced that the imbalances in the global economic system are such that the risks are high that another period of economic volatility like the Great Recession is not only likely but is now in the process of developing. While this time will be different in terms of its causes and symptoms (as all such stressful periods differ from each other in many ways), there will be a rhyme and a rhythm that feels all too familiar. That should actually be good news to most readers, as the last 14 years have taught us a little bit about living through periods of economic volatility. You will get to use those skills you learned the hard way. This will not be the end of the world if you prepare properly. In fact, there will be plenty of opportunities to take advantage of the coming volatility. If the weatherman tells you winter is coming, is he a prophet of doom? Or is it reasonable counsel that maybe we should get our winter clothes out? Three caveats before we get started. One, I am often wrong but seldom in doubt. And while I will marshal facts and graphs aplenty to reinforce my arguments, I would encourage you to think through the counterfactuals presented by those who will aggressively disagree. Two, while it goes without saying, you are responsible for your own decisions. It is easy for me to say that I think the bond market is going to go in a particular direction. I can even bet my personal portfolio on my beliefs. I can’t know your circumstances, but if you are similar to most investors, this is the time to make sure you have a truly balanced portfolio with serious risk management in the event of a sudden crisis. Three, give me (and Worth, whom I am going to draft to write some letters) some time to develop the full range of our ideas. To follow on with my weather analogy, the air is just starting to get crisp, and winter is still a couple months away. Absent something extraordinary, we are not going to get snow and a blizzard in Dallas, Texas, tomorrow. We may still have some time to prepare, but at a minimum it is time to start your preparations. So with those caveats, let’s look at an outline for a potential book called Sea Change. Prologue I turned publicly bearish on gold in 1986. At the time (a former life in a galaxy far, far away), I was actually writing a newsletter on gold stocks and came to the conclusion that gold was going nowhere – and sold the letter. I was still bearish some 16 years later. Then, on March 1, 2002, I wrote in Thoughts from the Frontline that it was time to turn bullish on gold. Gold at that time was languishing around $300 an ounce, near its all-time bottom. What drove that call? I thought that the future directions of gold and the dollar were joined at the hip. A bit over a year later I laid out the case for a much weaker dollar in a letter entitled “King Dollar Meets the Guillotine,” which later became the basis for a chapter in Bull’s Eye Investing. As the chart below shows, the dollar had risen relentlessly through the early Reagan years, doubling in value against the currencies of America’s global neighbors, causing exporters to grumble about US dollar policy. Then the bottom fell out, as the dollar made new lows in 1992. From 1992 through 2002 the dollar recovered about half of its value, getting back to roughly where it was in 1967. Elsewhere about that time, I predicted that the euro, which was then at $0.88, would rise to $1.50 before falling back to parity over a very long p eriod of time. I believe we are still on that journey. Weekly Market Comment

by John P. Hussman, Ph.D. October 13, 2014 Present conditions create an urgency to examine all risk exposures. Once overvalued, overbought, overbullish extremes are joined by deterioration in market internals and trend-uniformity, one finds a narrow set comprising less than 5% of history that contains little but abrupt air-pockets, free-falls, and crashes. In recent weeks, the market has transitioned to the most hostile return/risk profile we identify: the pairing of overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions with deterioration in market internals and price cointegration – what we call “trend uniformity” – across a wide range of stocks, sectors, and security types (see my September 29, 2014 comment Ingredients of a Market Crash). As in 2007 and 2000, we’re observing characteristic features of that shift. One of those features is that early selling from overvalued bull market peaks tends to be indiscriminate, as deterioration in market internals and the “average stock” often precedes substantial losses in the major indices. As of Friday, only 28% of NYSE stocks are above their respective 200-day moving averages. In the current cycle, both the Russell 2000 small-cap index, and the capitalization-weighted NYSE Composite set their recent highs on July 3, 2014, failing to confirm the later high in the S&P 500 on September 18, 2014. Through Friday, the NYSE Composite is down -7.3% from its July 3rd peak, and the Russell 2000 is down -12.8%, while the S&P 500 is down only -4.0% over the same period. What’s happening here is that selling is being partitioned in secondary stocks, and more recently high-beta stocks (those with greatest sensitivity to market fluctuations). Market action is narrowing in a classic pattern that reflects the effort of investors to reduce risk around the edges of their portfolios, in what typically proves an ill-founded belief that a falling tide will not lower all ships. Abrupt market losses are typically not responses to obvious “catalysts” but instead reflect a shift in investor preferences toward risk aversion, at a point where risk premiums are quite thin and prone to an upward spike to normalize them. That’s essentially what’s captured by the combination of overvalued, overbought, overbullish coupled with deteriorating internals. Another characteristic of these shifts is increasing volatility at short intervals – what I described at the 2007 peak and in early-2008 by analogy to “phase transitions” in particle physics. The extreme daily and intra-day market volatility in recent sessions is typical of that dynamic. Warning: Examine all risk exposures by Barry Ritholz October 13, 2014 Here we are, 10-plus months into the year, and we have nothing to show for it. At least, that is the case if we measure our progress by the gains (or losses) of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. The index is now unchanged for the year after last week's losses. The previously one-direction market has suddenly recalled what volatility looks like, having for the most part forgotten. Yes, stocks go up AND down. At the beginning of the fourth quarter, the Standard & Poor's 500 Index was up about 7 percent for the year; those gains have now been cut by more than half. The Russell 2000 small-cap index was already down almost 5 percent, and the past few weeks have added to the red. The Nasdaq 100 is still positive on the year, but has given back some of its gains. I can't tell you what will happen in the coming weeks or months, nor can I tell you what to do, not knowing your time horizon, risk tolerance and client base. I can, however, bring to your attention some interesting data points you may not have been aware of: • Since 1928, markets have averaged about three 5 percent corrections each calendar year; Then there is the concern about October as the worst month of the year for the stock market. The month has a bad reputation, likely due to a few outlying events that occurred in the past: The 1987 crash was less than 30 years ago, and even those traders who weren't yet born are familiar with the details of that particular episode. (I always recommend Tim Metz’s "Black Monday" for anyone who wants to understand what happened).

The 1929 crash (Oct. 29, "Black Tuesday”) also occurred in this month. The Great Depression -- the worst economic crisis in U.S. history -- followed. Is it any wonder traders can be superstitious about October? Ned Davis Research noted that of the “69 major trend changes since 1900, nine took place in October.” Mark Hulbert observes that while this “is higher than the monthly average of 5.75, October’s total is neither statistically significant nor unique.” As the "Stock Traders Almanac" is fond of pointing out, the six months that follow October are on average the best half of the year for equities. Whether that is because October affords a better entry price or is due to some other factor is both hotly debated and unresolved. The key question for investors is what to do in the face of this data. The simple truth is that we don't know whether this is going to be a run-of-the-mill 5 percent pullback, a deeper 10 percent correction, or a full-blown bear market. I hope for the middle outcome, while suspecting and fearing the third -- but that's only a wild guess. I suspect most investors will undertake one of three options: Benign neglect: They will ignore all of the goings on because they are autopilot investors. Their approach is to ride it out, making few moves other than regular portfolio rebalancing. These folks tend to do well over the long haul, but have little to talk about at cocktail parties. Over-reaction: These traders digest a massive amount of information via the media. They will obsessively consume as much news as possible before undertaking a series of radical changes in their holdings. Their performance may not be optimal, but they are great for anyone who toils in the world of commission-based compensation. Cautious contemplation: These are the investors who approach markets with a zen-like calm. They spend much of their time carefully thinking about the impact of their own actions on their returns. They are, for the most part, sociopaths who can disengage their emotions from their trading. What kind of trader are you? by Michael Sincere

October 13, 2014 Volatility has returned to the market. To be specific, the market has rallied, sold off, rallied, and sold off, all in one week. This is ideal for day traders but unnerving for individual investors. It is also a big red warning sign. To refresh your memory, last week every rally failed, so the market ended the week on its lows. Even the October 8th rally of 274 points reversed direction the next day. It was a monster rally based on the FOMC minutes, which revealed member’s concern for global growth. Got that? The market rallied on bad news. In the mixed-up world of Wall Street, that meant interest rates would remain low. Unfortunately for the bulls, the next day the market fell by 334 points. That’s volatility! In nontechnical terms, the October 8th manic rally was a head fake. It might have cheered amateur investors, but in reality, this has become one of the most dangerous markets since 2008. Facts are hard to dispute but easy to spin. Already, the Russell 2000 RUT, +0.50% is in a 10% correction. Judging by history, the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, -0.12% and S&P 500 SPX, -0.22% shouldn’t be far behind. A major correction or crash would be definitive proof this market is wearing no clothes. Failed rallies Failed rallies are extremely significant. Previously, whenever there were major or minor selloffs, buy-on-the-dippers would come in and change the market’s direction. On a chart, you’d see a distinctive “V” pattern as buyers overwhelmed sellers. This pattern has continued for months — until recently. On the market’s worst days, the Fed would conveniently appear with a new QE program or a promise to keep interest rates low for a considerable time (that’s getting old). Soon, though, these bandages will not work. Failed rallies mean the party is almost over and a bear market is getting closer (and may even have arrived). In addition to failed rallies, look for more intraday reversals (from a rally to a selloff), and a strong selloff into the close. For years, no matter how bad the news, it was either forgotten by the next day or spun as positive. As the bull market comes to an end, the market will finally react negatively to bad news. Sell into rallies Lately, there has been a tug-of-war between the bulls and bears. For the most part, the bears have been winning. If that pattern continues, many traders will sell on the rallies instead of buying on the dip. If selling on the rallies continues to work, that’s further evidence this bull market is on its last legs. The bulls are going to have to work hard for their money this year, something they are not accustomed to. And the bears will still have to manage explosive one-day rallies. This is what makes this market so dangerous. It takes a long time for sentiment to change from overconfidence to fear, and right now we’re in the early stages. The recent volatility has upset investors, but there is still little fear. When fear does hit the market, there will be a mad rush out the door that will remind investors of 2008. At the moment, it’s too early to proclaim that a bear market has definitely begun. Keep in mind that bull markets do not end in a week, as topping out can take time. In addition, bear markets often begin slowly and secretly, and arrive before most investors realize it. I’m convinced we’re close to the end of the topping-out process, but we still need more evidence. The increase in volatility VIX, +1.51% is a significant clue. There are other clues. For example, New Highs-New Lows have been flashing warning signs for weeks, and the NYSE Advance-Decline line topped out in late August. Although no one can time a market top, these indicators should not be ignored. In fact, judging by the technical, fundamental, and sentiment indicators, crunch time is getting closer. Be prepared to take defensive action Remember, Mr. Market always has the last word. My advice to investors: Buying on the dips could be highly dangerous. Review your portfolio and take defensive actions to protect it. This includes buying put options or hedging with ETFs if you are experienced. If you’re not, consider selling a portion of your stock portfolio. Bottom line: Some believe the long-anticipated correction has finally arrived. My view is that it could be worse — the end of the bull market. Take action before too much damage is done to your portfolio. The last thing you want is to try to get out when everybody else is selling. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed