Ambrose Evans-Pritchard - Global banks issue alerts on China carry trade as Fed tightens, yuan falls30/3/2014

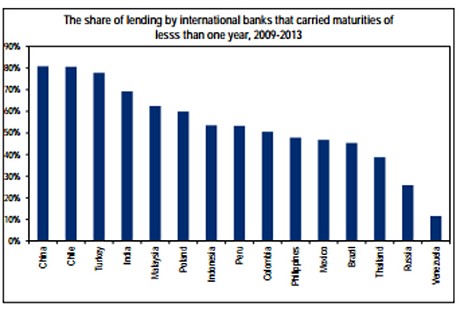

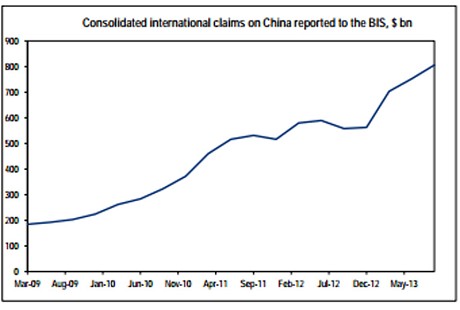

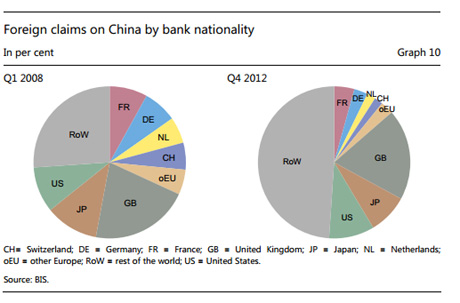

Citigroup tells clients to brace for second phase of the "taper tantrum" that rocked emerging markets last year, but this time with China at the eye of the storm By Ambrose Evans-Pritchard 30 March 2014 Three of the world's largest banks have warned that the flood of "hot money" into China is at risk of sudden reversal as the yuan weakens and the US Federal Reserve brings forward plans to raise interest rates, with major implications for global finance. A new report by Citigroup told clients to brace for a second phase of the "taper tantrum" that rocked emerging markets last year, but this time with China at the eye of the storm. “There’s a dangerous scenario in which the combination of rising US short-term rates and a more volatile RMB (yuan) could lead to a rather large capital outflow from China,” said the report, by Guillermo Mondino and David Lubin. They argue that China's credit boom has become a "function" of external dollar funding, mostly through offshore lending in Hong Kong and Singapore to circumvent internal curbs. It is a powerful side-effect of super-loose policies by the Fed, which the Chinese have been unable to control. If so, this may snap back abruptly as dollar liquidity dries up and fickle money returns to the US. Bank lending to emerging markets has surged by $1.2 trillion (£720bn) over the last five years to $3.5 trillion. The banks have funded most of these loans from short-term sources, leaving the whole nexus extremely vulnerable as the US prepares to tighten. The Fed caught markets badly off guard earlier this month when it suggested that interest rates would jump from near-zero to 1pc next year and 2.25pc the year after, a much faster pace than expected. Half of this foreign lending is linked to China, where dollar loans have jumped by $620bn since 2009. Roughly 80pc are at maturities of less than one year. The report warned that higher rates might “erode bank’s willingness to roll over their cross-border loans to borrowers in China”. Speculators have been borrowing dollars to buy Chinese assets, a flow known as the "carry trade". They often do so with leverage and through convoluted means, some involving use of copper or iron ore as collateral. The bet is that the yuan will strengthen, generating a near certain profit on the exchange rate. This has gone badly wrong as the central bank intervenes to force down the exchange rate, causing the yuan to fall 2.5pc against the dollar since January. Nomura issued a client note on Friday warning that the carry trade is “reversing gear”, describing a break-down of discipline in which almost everybody in China from investors, to manufacturers, exporters, and commercial banks have been playing the game. Most of the borrowing has been in dollars and yen on the Hong Kong market. Wendy Liu, Nomura’s China strategist, said investors are putting too much hope in the promise of fresh stimulus and infrastructure spending, ignoring the risks of a weak yuan. She said devaluation is a double-edged sword. It helps cushion the shock of China’s economic slowdown, boosting “the razor-thin margins” on exporters along the Eastern seaboard. It may also mitigate the “coming wave of credit defaults”. But is also exposes the fragility of the system. A view is gaining credence that the weak yuan is an early warning sign that “China's credit bubble may implode imminently”, she said. The Bank for International Settlements caught the attention of central banks across the world -- especially the Bank of England -- with a report last October warning that foreign loans to China are now large enough to risk a repeat of the 1998 financial crisis in Asia. “They have more than tripled in four years, rising from $270bn to a conservatively estimated $880bn in March 2013. Foreign currency credit may give rise to substantial financial stability risks associated with dollar funding,” it said. Analysts say dollar loans -- to firms, not the Chinese state -- have since risen to $1.2 trillion. Almost a quarter come from British-based banks. The BIS said the loan-to-deposit ratio for foreign currencies in China has doubled from 100pc in 2005 to 200pc today. Much of this has been through foreign exchange swaps and forms of credit that are hard to track.

China has $3.8 trillion of foreign reserves and ample monetary fire-power to shore up its financial system if need be. The banks are an arm of the state. The authorities can unleash $2 trillion of credit by slashing the reserve requirement ratio (RRR), currently 20pc. It was 6pc in the late 1990s. The question is whether President Xi Jinping wishes to do so. The current monetary squeeze has been deliberately engineered to crush speculators and prick the bubble before it is too late. Mr Xi's "Third Plenum" reforms aim to break China's reliance on excess credit, and on a catch-up growth model beyond its sell-by date. The paradox is that western lenders may be as much at risk -- or more so -- than the Chinese themselves. Credit Suisse says HSBC is heavily exposed, generating a large chunk of its profits from trades linked to China. The Swiss bank says the speculative part of the carry trade has reached $200bn and entails an intricate web of manoeuvres through Hong Kong. “Various indicators point to stress in the system. The risk of a mis-step is increasing,” it said. Citigroup said dollar lending to Brazil, India, Indonesia and Turkey has also been enough to create “some threat to external stability”. Outflows will have the effect of squeezing domestic credit, and risk pushing these countries into deeper downturns. The worry is different from last year's “taper tantrum” when the Fed's tough talk set off a 100 basis point rise in 10-year US bond yields, driving up global borrowing costs and triggering flight from emerging markets. Mr Lubin said the Fed's shift was the cause of China’s “nasty liquidity crunch” in June. This time bond yields have been better behaved. Citigroup says investors may be taking false comfort, concluding prematurely that the emerging market stress is over. The Achilles Heel in 2014 may prove to be the Fed's short-term rates. By Stephen Gandel

Fortune Magazine March 24, 2014 The money manager argues that the Fed's interventions have ruined the very recovery it was supposed to stimulate and that the market is poised to disappoint investors. FORTUNE -- If you hate the Federal Reserve, you have a new hero. A few weeks ago, Jeremy Grantham, the co-founder of money management firm GMO, called newly appointed Federal Reserve chairman Janet Yellen "ignorant" in the New York Times. He also said the reason for the slow recovery was not the severe financial crisis, continued high unemployment, or the many standoffs in Washington. Instead, he blamed the Fed for ruining the recovery it was supposed to stimulate. To someone who believes in the laws of economics, it's hard to overstate how odd that claim is. It's positively bonkers. Low interest rates stimulate the economy. The Fed has done everything in its power to keep interest rates down, lower and longer than anyone can remember. That should have helped the economy. And yet the recovery has been just meh. So, either Grantham is bonkers, or he is onto something. Fortune recently caught up with him to find out. Fortune Magazine - You believe the Fed's policies, particularly quantitative easing, have slowed the recovery. What's your proof? Jeremy Grantham - It's quite likely that the recovery has been slowed down because of the Fed's actions. Of course, we're dealing with anecdotal evidence here because there is no control. But go back to the 1980s and the U.S. had an aggregate debt level of about 1.3 times GDP. Then we had a massive spike over the next two decades to about 3.3 times debt. And GDP over that time period has been slowed. There isn't any room in that data for the belief that more debt creates growth. In the economic crisis after World War I, there was no attempt at intervention or bailouts, and the economy came roaring back. In the S&L crisis, we liquidated the bad banks and their bad real estate bets. Property prices fell, capitalist juices started to flow, and the economy came roaring back. This time around, we did not liquidate the guys who made the bad bets. FM - Can you really blame the Fed for the bailouts? That was an act of Congress. JG - I don't like to get into the details. The Bernanke put -- the market belief that if anything goes bad the Fed will come to the rescue -- has had a profound impact on people and how they act. FM - Okay, but that's still not proof that quantitative easing slowed the recovery. JG - There's no proof on the other side, that the economy is any stronger from quantitative easing. There's some indication that the crash would have been worse and the downturn would have been sharper had the Fed not stepped in, but by now the depths of that recession would have been forgotten, the system would have been healthier, and we would have regained our growth. FM - It's economic doctrine that lower interest rates boost the economy. Are you saying that's wrong? JG - Economic doctrine says the market is efficient. My view of the economy is not really principle-based. Higher interest rates would have increased the wealth of savers. Instead, they became collateral damage of Bernanke's policies. The theory is that lower interest rates are supposed to spur capital spending, right? Then why is capital spending so weak at this stage of the cycle. There is no evidence at all that quantitative easing has boosted capital spending. We have always come roaring back from recessions, even after the mismanaged Great Depression. This time we are not. It's anecdotal evidence, but we have never had such a limited recovery. FM - But the Fed does seem to have boosted stocks. Even if it did nothing else, doesn't a better market help the economy? JG - Yes, I agree that the Fed can manipulate stock prices. That's perhaps the only thing they can do. But why would you want to get an advantage from the wealth effect when you know you are going to have to give it all back when the Fed reverses course. At the same time, the Fed encourages steady increasing leverage and more asset bubbles. It's clear to most investing professionals that they can benefit from an asymmetric bet here. The Fed gives them very cheap leverage on the upside, and then bails them out on the downside. And you should have more confidence of that now. The only ones who have really benefited from QE are hedge fund managers. FM - Okay, but then I guess that means you think stocks are going higher? I thought I had read your prediction that the market would disappoint investors. JG - We do think the market is going to go higher because the Fed hasn't ended its game, and it won't stop playing until we are in old-fashioned bubble territory and it bursts, which usually happens at two standard deviations from the market's mean. That would take us to 2,350 on the S&P 500, or roughly 25% from where we are now. FM - So are you putting your client's money into the market? JG - No. You asked me where the market is headed from here. But to invest our clients' money on the basis of speculation being driven by the Fed's misguided policies doesn't seem like the best thing to do with our clients' money. JG - We invest our clients' money based on our seven-year prediction. And over the next seven years, we think the market will have negative returns. The next bust will be unlike any other, because the Fed and other centrals banks around the world have taken on all this leverage that was out there and put it on their balance sheets. We have never had this before. Assets are overpriced generally. They will be cheap again. That's how we will pay for this. It's going to be very painful for investors. The roundabout path to profits: Mark Spitznagel on the Dao of Capital

How a hedge fund manager with floor trader roots embraces the Q Ratio, Austrian economics, tail hedging, libertarianism and Daoism to prepare for the next market crash. Futures Magazine By Daniel P. Collins April 1, 2014 Mark Spitznagel is an accomplished trader and hedge fund manager who has learned to take advantage of market distortions he blames on an overly involved Federal Reserve and government, while preparing for the consequences of those distortions. Instead of fighting what he knows is an illogical distorted market he has learned to ride those irrational markets while preparing for the inevitable snap back, where he then can profit in an exponential fashion through the perfecting of tail hedging strategies. However, his book “The Dao of Capital: Austrian Investing in a Distorted World” is not an explanation of his trading strategy but an in-depth study of economics and human nature, the inevitable result of which is the philosophy of building a successful enterprise through the understanding of the roundabout, and learning to delay gratification to gain an advantage down the road. He does it through the study of Austrian economics and the application of the roundabout method of investing. Spitznagel could have simply have written that investors need patience and must avoid the temptation of the quick profit; that building a successful strategy, and life, involves a longer-term approach foregoing instant gratification; that establishing a solid foundation while appearing not to create progress puts you in position for much greater success later on. He did not do that. Instead, he takes you on a tour of history and nature that illuminates these long held truths. Just as the technical trader delves into cycle analysis and Fibonacci numbers, Spitznagel illustrates how these truths are imbedded in history and nature and are not just platitudes to throw around. In the end his message is simple, but by providing the historical underpinnings he brings them to life in a much more vibrant way. He travels a long way to come to a pretty simple message. It is through his vast research and study that he shows that this message, though simple, is essential. He has documented how it has been so throughout history. Futures Magazine: Your book cites some of the most accomplished economists, military and historical figures as inspiration but at the top of your list is an old grain trader and family friend Everett Klipp. Why? Mark Spitznagel: He was a close family friend, very close to my dad. I caught the [trading] bug from him early on and he said simply ‘to be successful you have to love to lose.’ Even at the [Chicago] Board of Trade, it is not like pit traders do this. But when I was 14 I thought that’s what trading was. This is the discipline of trading, loving to lose and nothing about winning. I immersed myself in it and became obsessed with the grain markets. Through high school and even through college, I wanted to be a corn trader. I clerked for many summers in the grain [room] and ultimately the bond [room]. It slowly became obvious that is where someone’s got to be. FM: It is no huge revelation that a lot of our recent economic problems can be blamed on short-term thinking; never looking beyond the next quarter. You take a circuitous route in your book to describe this. Is that on purpose? MS: It is on purpose. The whole point is there is a lot you have to build up along the way. There is a path you have to follow to get somewhere and it is not the direct path. For instance, it is not enough to give someone an investment strategy, the key is what is underlying that investment strategy, why these things should work, what the thinking behind it is. It is very easy to say this is a strategy that works and it will continue to work. There are data mining issues with that. You need to approach trading in a much more deductive way. It was the point to build up the necessary tools to code to the strategy. FM: It seems that we intuitively know some of these things but often don’t act on it. MS: People say it is a long term thing. It is almost a cliché to say that. They use it as an excuse for what is not working at the moment. What I am talking about is not just about waiting, it is about working in the present to gain an advantage in the future as opposed to just putting something on and twiddling your thumbs and watching it work. Yes, we are all very short-term minded. Corporate managers are thinking about the next quarter. This is all very rational for them to do. There is the [Stanford professor Walter] Mischel study (an experiment to determine whether kids would be willing to wait to get more marshmallows or take one immediately). It turns out that the reason they don’t wait is not because of impatience, it is that they don’t believe you are going to come back with more. Any investment manager is right to think that if I don’t get my marshmallow now, do well now, you are not going to give me an opportunity to do better later. And they are right about that. It is a structural problem. These people are acting very rationally based on the structure of these industries. I firmly believe the big problem here is one of being trapped in the present and all that matters is that next slice of time. It is both a structural problem in history and our psychology. FM: You successfully called the market turns of 2000 and 2008. Was your tail hedging strategy perfected or was it just forming? MS: I was on the floor from 1993-97. In ’98 I was a swaption trader at Credit bank primary dealer arm. In 1999 I started a hedge fund with Nassim Taleb, who was at the [Chicago Mercantile Exchange] when I was at the CBOT; 2000 was our big play there. In 2005 I went to Morgan Stanley within its stat arb group. In 2007 I left to start Universa [Investments] and we all know what happened in 2008. FM: A lot of people saw the 2000 crash coming as the market appeared overbought throughout the late 1990s but lost money by being wrong on the timing. Is your strategy a fix for that problem? MS: Absolutely. You can’t short markets that are running like that. You are going to blow yourself up. It goes back to Everett. That’s the reason I approach market this way: the idea of taking a one tick loss. If you want to trade that market with S&Ps you would short it, but when you are wrong you will have a tight stop. And throughout the ’90s you would have taken a lot of losses. Eventually you would have been right, whether you would make up all your losses, I can’t say. What I do with options is nothing more than a fancier way to do that. Right now I would say the market is massively distorted, we are going to see a huge sell-off but I would never advise someone to be short this market. You would blow yourself up. The market will balance itself; as it has in all the other bull moves caused by distortions in the last 100 years. It managed to right itself but the path there is difficult and there is no telling how far it can go. In the late ’90s clearly [Fed Chair Alan] Greenspan was the driver of that boom. There was a nice believable theme behind it that we were in a new economy. The market went further than it ever had in recorded history. Here we are again on the cusp. If the market rallies much from here, now we are back in this territory like 1999. It is possible the market could double from here or triple from here. I happen to think it is not the likely path. FM: Isn’t it different now. In the ’90s we had a booming economy. No one would confuse the last six years with a booming economy, we know it is struggling and the Fed is trying to keep us above water waiting for stronger growth to happen. MS: Agreed. But I would argue in both situations ultimately there were delusions. The booming economy of the ’90s was happening but it was not based on anything real. At some point monetary distortion can easily lift asset prices but it also could make it look like there is activity in the economy that is artificial. They both had similar sources. The late ’90s look very different than today and for that reason it will probably be very difficult for us to go too much higher. FM: What was the misallocation in the ’90s? It seem that they were constantly raising interest rates anytime growth went beyond 3.5%. MS: It was the Fed keeping interest rates too low. Rates were too low in the ’90s. We don’t understand why Greenspan kept rates as low as he did in 1996. The general argument was rates were too low for too long. I know by today’s standards it seems benign. They were artificially low in the ’90s. FM: In 2002 when GDP was growing by more than 4% two quarters in a row, the Fed went from 1.75% down to 1%. Is that the seed of the current problem? MS: Yes. The same thing happened. How people can’t see how that for instance created the real-estate boom is inconceivable. The question is how much do we bring Fed Funds back up again. In 1996, why didn’t you let rates go up more quickly than you did? And rates were lowered in ’02 all for the same reasons. You change the structure of the economy when you artificially move them in the first place. When the government sets the price of things typically our culture is such that we don’t like it. If the government set the price of LCD TVs we would think there is something weird about that, and yet we don’t think it is weird for them to set the price for the most important price in the economy, which is interest rates. We don’t have a free market in interest rates. When you do that, complex distortions happen. FM: How patient would you have been if you developed this strategy in 1990 and had to wait a long time for the market to correct? MS: You had to wait until the mid-1990s before the MS Index or Tobin’s Q ratio, put you at the levels where it is today. Let’s remember 1982 was a generational buy and then the market ripped. It wasn’t until 1995 or 1996 where it reached that level where every market topped in the last 100 years: 1917, 1929, 1937, (1973) and 1996. It wasn’t until 1996 if you were following this MS Index that you would have stated maybe it is different this time because the market screamed from there but throughout the first part of the 1990s, it was not terribly overvalued. FM: Your philosophy is based on non-intervention but 2008 was pretty extreme crisis. Do you think the Fed needed to do anything? MS: People who are Libertarian are always put in this unenviable position where we look like people who don’t care because we are saying you shouldn’t do anything; you should let the forest burn; let people suffer. It is unfair to start with the tragedy, you have to start with the build-up. It is interventionism that got us there in the first place. Go to my forest analogy that is central to my book. If you don’t allow any forest fires for many, many years and then all of a sudden a little fire starts at that point you get painted in a corner where you have to put out every fire. And now if you step aside at that point now the whole forest could get destroyed. The mistake you made was not letting the little fires burn in the first place. FM: To continue with your analogy; now there are houses built in the path and we can’t just let people’s homes burn down. Right? MS: In the economy—and I have a 100 years of evidence to show this—if people are going to build homes in this parkland where we don’t let fires go, those homes are doomed regardless. We can continue to put out fires but that is only going to make a bigger fire later. It is inevitable that this thing is going to blow. The question is how long are we going to let it go and how many people are we going to let get trapped into building more homes in this tinderbox, to extend your analogy. Should we have done nothing in 2008? I strongly believe that we should have let the market correct itself. I strongly believe that TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program) was a terrible thing to do. I strongly believe that the auto companies should have gone through bankruptcy. FM: So you are saying we need to go cold turkey on intervention? Haven’t we gone beyond the point of no return in Keynesian economics? This was not started in this administration or this Fed. It is a process that has taken decades. How would you get to where you want to go from where we are right now? MS: To start off, what Bernanke has done is unprecedented. We haven’t manipulated the yield curve like this ever. While there have been monetary manipulation that has caused booms and busts—and I strongly believe that booms and busts are caused by monetary interventions and it is not a natural feature of capitalism—but what Bernanke has done has been an experiment the likes of which we have never seen. Look at the history of rates. The last four years will stand out. It is very extreme and it is scary and the move down will be worse. Are we past the point of no return? I think we are. If this is the way the Federal Reserve Chairman will have to look at it. [New Fed Chair Janet] Yellen is going to have to deal with the consequences. All this talk of tapering. I don’t think it is going to be an option for the Fed. I don’t think the Fed can taper. If you saw a headline; ‘Yellen decides to let all interest rates float, free market in interest rates.’ Then you would see the market down 50%. Most people agree with me on that. I don’t know what the yield curve would look like but the market would crash. What they are doing now is waiting and hoping that something happens in the economy that allows them to taper. They are going to be waiting for a long time. You will end up with a situation that the Fed’s hand is forced or with what the Fed’s is doing stops mattering and that will come when more leverage in the system is not possible and we are probably not far from that. FM: But the Fed is tapering. MS: Those expectations keep on getting pushed back. I agree with your statement that we are passed the point of no return. I don’t think the Fed can taper without crashing the market. The market is only at where it is at because of the Fed. I don’t want to predict what the Fed will do but one way or another it won’t matter what they want to do. Unless the Fed is willing to crash the market, which I don’t think it is, I don’t see this big taper happening willingly. FM: Jim Sinclair said to us two years ago that quantitative easing was the only tool Bernanke had to avoid a catastrophe and the only measure of success is that when the economy begins to grow more robustly whether or not he can drain the excess liquidity safely. Do you agree? MS: I think you will be waiting a while for it. When companies start borrowing not to buy back their own stock, not just to raise their dividend but instead borrow in order to do more capital expenditures, then we will start seeing some growth but don’t hold your breath for it. I see his point: Will the Fed be able to drain the liquidity fast enough to avoid inflation? FM: Was QE not necessary? MS: It depends on what you are trying to do. If you are trying to prop up the stock market, if you are trying to save people who own risk assets like banks, it was absolutely necessary, in the short-term. There is no doubt that the Fed is capable of pushing risk assets. We shouldn’t be surprised that the market has gone up and continues to go up but it can’t go on forever. It is an artificial world we are living in. If we were able to manipulate it like this permanently than obviously this would be a formula that would work everywhere. FM: I don’t think anyone believes that this is good policy in general just that it was necessary to avoid a disaster. We kick the can down the road to a point that growth improves and we can better handle the excess. Can it work? MS: You certainly are looking for a precise, perfect scenario. I am not necessarily calling for hyperinflation but with the money being printed it is [possible]. Be careful what you wish for. If you start getting growth I totally recognize how we could get very high inflation, but first you have to have growth, you have to have people investing capital. Interest rates are the most important economic variable out there. Entrepreneurs base their activities on that, whether you engage in production what is your return over your cost of capital. When interest rates are very low in a free natural market that means that there is a lot of savings, people aren’t consuming but they are saving. They call that a consumer recession, it is a very nice homeostatic system. Entrepreneurs respond to that. It incentivizes them to extend their period of production. Austrians call that more roundabout. They create more efficient production. The civilization and economy progresses and that production completes around the time that consumers are ready to consume again and save less. Remember we save to consume more later. There is a nice temporal structure that goes on in the economy. But what happens when interest rates are low for artificial reasons; actually the opposite happens. The whole point of low interest rates is not only do central bankers want to goose asset prices but they are trying to get entrepreneurs to invest more and when they invest more, progress comes from them. But when interest rates are lower than what we natural want it to be based on our time preferences, it is now this weird thing where people are trying to chase yield just to make a little carry. Zero rates are unacceptable to people. So we are looking for dividend yielding stocks. At the end of the day investors are not looking for more roundabout production but instead are looking for companies with high dividends. This is considered a puzzle by Keynesian Economists. [Paul] Krugman himself called it a puzzle. When Tobin’s Q is high and rates are low why don’t companies invest more? It makes perfect sense because it is a distorted environment. They are not low for natural reasons. This is why we shouldn’t expect the economy to progress just because rates are low. The opposite is happening now. Many government programs create the opposite affect [of its design]. [Economist Ludvig von] Mises says when a person gets run over by a car, the last thing he needs is for that car to then back over him. And that is the cycle that we are in. Each time the government intervenes, it is making things worse. We are worse off now than when we were in 2006-07, for no other reason than there is no more back stop. FM: But these misallocations have been going on for a long time. Is there a way to do this gradually or does it have to happen all at once? MS: I would be perfectly happy with a taper that ends over a period with a free market in interest rates. It doesn’t have to be that we close the Eccles (Federal Reserve) building over night. It could be gradual. [But] if the market caught wind of what they were doing it would crash. A taper [with a goal] of a market determined interest rate would force discipline on our fiscal policy. So much of the debt that we are running up right now is because our rates are artificially low. I would be all for that. FM: Many experts suggested that regulations and policy needs to be countercyclical. Do you agree? MS: They look the other way when everything is going well. I totally agree. But it shouldn’t be so much about them in the first place. FM: Discuss your trading philosophy and how it can be used. MS: You simply step aside when markets get distorted. What does that mean? You have to watch all your friends making money when you are sitting aside making nothing. You are no longer focusing on your returns today but the return opportunities you will have later when markets reset. I am thinking about the advantage that you will have with dry powder when the markets crash and not about return today. By doing nothing I am doing something real big. I am allowing myself opportunities later. A higher level example of that is what I do, which is instead of doing nothing you actually have positions that will [create] a tremendous amount of cash. What is the hardest position to have right now? It is cash. The Fed knows what it is doing. It is pushing you out of something it doesn’t want you in. It is not an accident. If your focus is only on that next slice of time like all the professionals, then it is not an option. If you can plan for those other slices of time, they should be far more important to you than the current one. If you had followed the strategy you would be far ahead of the market. You would have been out of the market since 1996, which is a very hard thing to do. FM: In your strategy do you constantly have the same hedge on or do you increase and decrease it based on the MS Index? MS: You can increase it or decrease it. I showed an example in the book that it is the most effective when there is a high MS index; when it is low there is not a lot of room for a systemic crash. When that is low a tail hedge is not critical. The great thing about what I do is that the more distorted the market gets, the cheaper my trade is and the better the risk/reward looks. It is a very convenient property. For instance, the VIX tends to go down when the S&P rallies. FM: How much do you underperform the market when things go well? MS: It is complicated because I do some complex hedges and spreads. What I talk about in the book is a very simplistic naïve representation where you are just buying out-of-the-money puts. But it costs you a low single digit percentage a year—in that naïve case. I could be short premium meaning if the market shuts down I am earning premium but if the market crashes I am long gamma. FM: There has been a lot of criticism of alternatives. Is this dangerous given that it will push people to long equity strategies? MS: All bets are interconnected. There is one big systemic bet that everyone is taking right now. Diversification is hard to come by. It is a shame. We are very good extrapolators. FM: How will the current distorted market be resolved? MS: At some point whether it is quickly or not [there is so much leverage a system can take] markets will crash. In classical economic perspective they say that when interest rate get lower we have higher liquidity preferences, people don’t want to lend anymore, they don’t want to borrow anymore. That is why balance sheets at banks get so bloated. It will probably happen quickly when it happens but at the end of the day when markets are this distorted you will find your way back. FM: What is your goal with the book? It includes concepts that are very easy to understand but difficult to execute in investing and in life. MS: That’s kind of my thinking. It sounds like a cliché. These are the tools of what got us here in the first place. The idea of a roundabout. Focusing on the means and not the ends. It is so obvious but it helps to understand the role it has played. You can’t just focus on outcomes, you have to have something else to lean on. It is not empiricism that you should lean on because it can guide you down the wrong way so you need these concepts and in order to understand them and believe them [you have to see how they came about]. Half of it was good introspection for me. It is a travesty what the smaller investors go through so to me it was important to try and get people to understand this perspective. So much of Austrian theory is difficult to get through. Though I went about it in a roundabout way, my goal was to make it somewhat approachable. FM: For people to adopt this is it just going to take pain? Another crash or event to reorganize ourselves? MS: I think it will. And capitalism will be blamed again when it happens. All the scary stories that we heard when they jammed through TARP, a lot of it was overstated. I can’t prove it and I don’t think others can prove the other side of it. But this idea of the end of the world scenario is entirely wrong. We should look at this as a healthy process, as a cleansing process. We would be on the road to very healthy real growth today if we just let it cleanse itself. My ultimate message is one of great optimism. Seeing optimism in a crisis or a tragedy. It is a means to a much greater end. We need to recognize that. Politicians can’t because politicians will not get reelected during a crisis. They are rational to try and stop all pain. …We should have had more banks fail. by David Stockman

March 13, 2014 The greatest danger is the central banks. All the central banks are out of control. They have expanded their balance sheets in a way historians someday will properly and soberly describe as lunatic. So I think it’s extremely dangerous. No one has the foggiest idea of what land mines or explosive eruptions are out there. But it’s all out there and it’s just looking for a catalyst, looking for a match. There is an accumulating recognition that the environment is a lot more dangerous than people thought. Its not benign, it’s not that ‘the crisis of 2008 is over,’ and that ‘We’ve crawled along and finally we are nearing escape velocity,’ and all this nonsense you hear from Keynesians like Larry Summers and the economists at the IMF and the World Bank and so forth. I think what the marketplace of the world is beginning to realize is that the opposite is true — that we’re not getting stronger, better, and returning to normal, but instead the accumulation of all these anomalies and bubble finance effects is building huge tensions and instabilities . And as that happens, you get to an environment where some catalyst can set off a real selling panic. Stay alert, stay out of harm’s way, and don’t believe the constant refrain that ‘this dip is a buying opportunity.’ They have been for several years because the Fed and the central banks have made it so. But unless you believe that the central banks can just keep printing money forever and expanding their balance sheets at these crazy double- and triple-digit rates, then the answer is that it’s dangerous out there and the best thing to do is draw back, keep liquid, and keep out of the risk asset markets. --- David A. Stockman: Former Dir. of the US Office of Management and Budget (USOMB), Economic Policy Maker, Politician, Financier & Acclaimed Author - After leaving the White House, Stockman had a 20-year career on Wall Street where he joined Salomon Bros. He later became one of the original partners at New York-based private equity firm, The Blackstone Group and in 1999 started his own private equity fund based in Greenwich, Connecticut. Defying right- and left-wing boxes, his latest book a New York Times best-seller, The Great Deformation: The Corruption of Capitalism in America (2013), Stockman lays out how the U.S. has devolved from a free market economy into one fatally deformed by Washington’s endless fiscal largesse, K-street lobbies and Fed sponsored bailouts and printing press money. Evans-Pritchard - European banks face double hit from emerging market slide and ECB crackdown12/3/2014

OECD warns bond tapering by Fed has “only just begun” and threatens to trigger a fresh wave of capital flightBy Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

11 March 2014 The deepening slowdown in emerging markets is holding back global recovery and risks fresh financial strains in Spain, Britain and other European countries with large bank exposure to the bloc, the OECD has warned. Rintaro Tamaki, chief economist for the OECD club of rich states, said bond tapering by the US Federal Reserve has “only just begun” and threatens to trigger a fresh wave of capital flight from vulnerable parts of the emerging market nexus. “There remains a risk that capital flows could intensify,” he said. Mr Tamaki said Spanish bank exposure to developing countries is 35pc of Spain’s GDP, mostly through the operations of Santander and BBVA in Latin America. Exposure is 21pc for Britain and 18pc for Holland. The US is largely insulated at just 3pc of GDP. Much of Britain’s link is through lending to Chinese companies on the dollar market in Hong Kong. British-based banks account for almost a quarter of the estimated $1.1 trillion of foreign-currency loans to China. The OECD called on the Fed to go easy on bond tapering and said the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan may have to step up stimulus to prevent the recovery faltering. Mr Tamaki said the OECD’s leading indicator gauge for emerging markets peaked in January 2011 and has been declining relentlessly ever since, now made worse as Turkey, South Africa, Brazil, India and others tighten monetary policy to defend their currencies. “Given that emerging economies now account for more than half the world economy, the slowdown is likely to be a drag on global growth,” said the body. European banks are already under pressure from the ECB’s forthcoming stress tests. An ECB manual published on Tuesday signalled that these will be far more intrusive than previous rounds of tests by national regulators, widely viewed as a fiasco. Banks will no longer be allowed to cover up the true scale of non-performing loans by waiting for 120 or even 180 days before coming clean. “We will strictly enforce the 90-day rule,” said an ECB official. Once a borrower misses a payment by 90 days on any of its debt, everything it owes will be classified as a bad loan. The ECB will also carry out its own spot checks on €3.7 trillion of assets rather the letting banks reach their own rosy assessment, especially for “Level 3” assets that cannot easily be traded. “We will look closely at the trading books of around 30 large banks with Level 3 assets to see whether they are properly classified,” said one official. The ECB appears confident that the eurozone recovery is strong enough to withstand a tough approach, which could force banks to cut lending to meet capital ratios, and even lead to closures. Bank stocks barely moved on the new guidelines. Italy’s Unicredit rose more than 6pc despite a record loss of €14bn in the fourth quarter to cover bad loans from costly takeovers in Austria and central Europe. Investors were comforted by plans for a cost-cutting purge. Yet the ECB clampdown is a risky strategy at a time when EMU-wide private sector lending is contracting at 2.3pc, with a deep credit crunch for small firms in southern Europe. “I am very concerned about this,” said professor Richard Werner, from Southampton University. “There is a high risk that it could force banks to reduce lending. It could push banks in the periphery to the edge but it could also put pressure on smaller banks in Germany that provide 70pc of loans for small firms. “The ECB is far too tight already. Germany is providing the last speck of growth in the eurozone but even this is now threatened." Mauldin - The Problem with Keynesianism By John Mauldin March 09, 2014 Excerpt: Central banks around the world and much of academia have been totally captured by Keynesian thinking. In the current avant-garde world of neo-Keynesianism, consumer demand –consumption – is everything. Federal Reserve monetary policy is clearly driven by the desire to stimulate demand through lower interest rates and easy money. And Keynesian economists (of all stripes) want fiscal policy (essentially, the budgets of governments) to increase consumer demand. If the consumer can’t do it, the reasoning goes, then the government should step in and fill the breach. This of course requires deficit spending and the borrowing of money (including from your local central bank). Essentially, when a central bank lowers interest rates, it is trying to make it easier for banks to lend money to businesses and for consumers to borrow money to spend. Economists like to see the government commit to fiscal stimulus at the same time, as well. They point to the numerous recessions that have ended after fiscal stimulus and lower rates were applied. They see the ending of recessions as proof that Keynesian doctrine works. There are several problems with this line of thinking. First, using leverage (borrowed money) to stimulate spending today must by definition lower consumption in the future. Debt is future consumption denied or future consumption brought forward. Keynesian economists would argue that if you bring just enough future consumption into the present to stimulate positive growth, then that present “good” is worth the future drag on consumption, as long as there is still positive growth. Leverage just evens out the ups and downs. There is a certain logic to this, of course, which is why it is such a widespread belief. Keynes argued, however, that money borrowed to alleviate recession should be repaid when growth resumes. My reading of Keynes does not suggest that he believed in the continual fiscal stimulus encouraged by his disciples and by the cohort that are called neo-Keynesians. Secondly, as has been well documented by Ken Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart, there comes a point at which too much leverage on both private and government debt becomes destructive. There is no exact number or way of knowing when that point will be reached. It arrives when lenders, typically in the private sector, decide that the borrowers (whether private or government) might have some difficulty in paying back the debt and therefore begin to ask for more interest to compensate them for their risks. An overleveraged economy can’t afford the increase in interest rates, and economic contraction ensues. Sometimes the contraction is severe, and sometimes it can be absorbed. When it is accompanied by the popping of an economic bubble, it is particularly disastrous and can take a decade or longer to work itself out, as the developed world is finding out now. Every major “economic miracle” since the end of World War II has been a result of leverage. Often this leverage has been accompanied by stimulative fiscal and monetary policies. Every single “miracle” has ended in tears, with the exception of the current recent runaway expansion in China, which is now being called into question. (And this is why so many eyes in the investment world are laser-focused on China. Forget about a hard landing or a recession, a simple slowdown in China has profound effects on the rest of the world.) I would argue (along, I think, with the “Austrian” economist Hayek and other economic schools) that recessions are not brought on by insufficient consumption but rather by insufficient income. Fiscal and monetary policy should aim to grow incomes over the entire range of the economy, and that is accomplished by increasing production and making it easier for entrepreneurs and businesspeople to provide goods and services. When businesses increase production, they hire more workers and incomes go up. Without income there are no tax revenues to redistribute. Without income and production, nothing of any economic significance happens. Keynes was correct when he observed that recessions are periods of reduced consumption, but that is a result and not a cause. Entrepreneurs must be willing to create a product or offer a service in the hope that there will be sufficient demand for their work. There are no guarantees, and they risk economic peril with their ventures, whether we’re talking about the local bakery or hairdressing shop or Elon Musk trying to compete with the world’s largest automakers. If they are hampered in their efforts by government or central bank policies, then the economy stagnates. Keynesianism is favored by politicians and academics because it offers a theory by which government actions can become the decisive factor in the economy. It offers a framework whereby governments and central banks can meddle in the economy and feel justified. It allows 12 people sitting in a board room in Washington DC to feel that they are in charge of setting the price of money (interest rates) in a free marketplace and that they know more than the entrepreneurs and businesspeople do who are actually in the market risking their own capital every day. This is essentially the Platonic philosopher king conceit: the hubristic notion that there is a small group of wise elites that is capable of directing the economic actions of a country, no matter how educated or successful the populace has been on its own. And never mind that the world has multiple clear examples of how central controls eventually slow growth and make things worse over time. It is only when free people are allowed to set their own prices as both buyers and sellers of goods and services and, yes, even interest rates and the price of money, that valid market-clearing prices can be determined. Trying to control those prices results in one group being favored over another. In today's world, the favored group is almost always bankers and the wealthy class. Savers and entrepreneurs are left to eat the crumbs that fall from the plates of the well-connected crony capitalists and to live off the income from repressed interest rates. The irony of using “cheap money” to try to drive consumer demand is that retirees and savers get less money to spend, and that clearly drives down their consumption. Why is the consumption produced by ballooning debt better than the consumption produced by hard work and savings? This is trickle-down monetary policy, which ironically favors the very large banks and institutions. If you ask Keynesian central bankers if they want to be seen as helping the rich and connected, they will stand back and forcefully tell you “NO!” But that is what happens when you start down the road of financial repression. Someone benefits. So far it has not been Main Street. And, as we will see as we examine the problems of the economic paper that launched this essay, Keynesianism has given rise to a philosophical framework that justifies the seizure of money from one group of people to give to another group of people. This is a particularly pernicious doctrine, as George Gilder noted in our opening quote: Those most acutely threatened by the abuse of American entrepreneurs are the poor. If the rich are stultified by socialism and crony capitalism, the lower economic classes will suffer the most as the horizons of opportunity close. High tax rates and oppressive regulations do not keep anyone from being rich. They prevent poor people from becoming rich. High tax rates do not redistribute incomes or wealth; they redistribute taxpayers – out of productive investment into overseas tax havens and out of offices and factories into beach resorts and municipal bonds. Mark Spitznagel

USA Today March 9, 2014 What a waste of a crash. After enduring all that pain from the financial crisis and the Great Recession, five years from its depths we have little to show for it. It's true that certain asset prices have surged, but a chart of the S&P 500 looks disturbingly similar to the timing of the Fed's various rounds of "quantitative easing," suggesting an artificial bubble built on printing money. Have we learned nothing? Before the fall of 2008, Ben Bernanke misdiagnosed the coming financial storm. His medicine was just as bad. Thanks to his playing Dr. Frankenstein, pumping life into failing banks that should have been allowed to die, we have created an economic illusion. Interest rates are signals that provide important information to everyone in the economy. The Fed's artificially low interest rates induce investors to chase yield in risky projects that they normally would shun. Here's the paradox: Artificially low rates actually discourage patient investment, and create yield-crazed zombies that are only interested in what they can devour now. A lack of capital expenditure growth shows the Fed's folly. Although corporations are sitting on record cash levels, their net debt levels are back to their 2008 highs. This debt has not been spent on organic growth, but rather on stock buybacks and dividends. It's true that had the Fed not intervened, the crash of 2008 would have been even more painful and the recession more prolonged. But the bottom would have been a real foundation, solid as bedrock, from which meaningful, sustainable growth could occur. In short, we would have a natural, well-orchestrated dance of great patience, from which the economy would progress. Even more important, we would be on solid footing now, instead of teetering atop a bubble of inflated assets. Instead of toasting the success of the Fed, we would be better off recognizing the disconnect between reality and illusion. The illusion will shatter when the monster returns to its home, and asset markets return to reality. If we want a repeat performance of the last boom-and-bust cycle, current Fed policy is just the thing. Mark Spitznagel is the founder of the hedge fund Universa Investments L.P. and author of The Dao of Capital: Austrian Investing in a Distorted World. John Hussman

March 10, 2014 Excerpt: [I]n my view, it is incorrect to believe that the 2008-2009 market plunge and financial crisis were caused by the housing bubble. The housing bubble was merely the expression of a very specific underlying dynamic. The true cause of that episode can be found earlier, in Federal Reserve policies that suppressed short-term interest rates following the 2000-2002 recession, and provoked a multi-year speculative “reach for yield” into mortgage securities. Wall Street was quite happy to supply the desired “product” to investors who – observing that the housing market had never experienced major losses – misinvested trillions of dollars of savings, chasing mortgage securities and financing a speculative bubble. Of course, the only way to generate enough “product” was to make mortgage loans of progressively lower quality to anyone with a pulse. To believe that the housing bubble caused the crash was is to ignore its origin in Federal Reserve policies that forced investors to reach for yield. Tragically, the Federal Reserve has done the same thing again – starving investors of safe returns, and promoting a reach for yield into increasingly elevated and speculative assets. Thinking about the crisis only from the perspective of housing, investors and policy-makers have allowed the same process to play out more broadly in the equity market. On a quantitative basis, the overvaluation of the equity market is greater percentage-wise, and greater dollar-wise, than the overvaluation of housing in 2006-2007. We fully expect that from present valuations, U.S. stocks will produce zero or negative returns on every horizon shorter than 7 years. There is no antidote or alchemy that will allow a buy-and-hold approach to squeeze water from this stone. There is no painless monetary fix that will shift the allocation of capital toward productive investment and away from distortive speculation. Instead, one must wait for the rain. Impatient, uninformed investors are all too willing to wastefully scatter seeds onto this parched desert, thinking that this is their only chance to sow. To wait patiently in the expectation of fertile soil and rain is not an act of pessimism, but an act of optimism and informed experience. Excerpt - Seth Klarman, Baupost Grou:

Born Bulls In the face of mixed economic data and at a critical inflection point in Federal Reserve policy, the stock market, heading into 2014, resembles a Rorschach test. What investors see in the inkblots says considerably more about them than it does about the market. If you were born bullish, if you’ve never met a market you didn’t like, if you have a consistently short memory, then stocks probably look attractive, even compelling. Price-earnings ratios, while elevated, are not in the stratosphere. Deficits are shrinking at the federal and state levels. The consumer balance sheet is on the mend. U.S. housing is recovering, and in some markets, prices have surpassed the prior peak. The nation is on the road to energy independence. With bonds yielding so little, equities appear to be the only game in town. The Fed will continue to hold interest rates extremely low, leaving investors no choice but to buy stocks it doesn’t matter that the S&P has almost tripled from its spring 2009 lows, or that the Fed has begun to taper purchases and interest rates have spiked. Indeed, the stock rally on December’s taper announcement is, for this contingent, confirmation of the strength of this bull market. The picture is unmistakably favorable. QE has worked. If the economy or markets should backslide, the Fed undoubtedly stands ready to once again ride to the rescue. The Bernanke/Yellen put is intact. For now, there are no bubbles, either in sight or over the horizon. But if you have the worry gene, if you’re more focused on downside than upside, if you’re more interested in return of capital than return on capital, if you have any sense of market history, then there’s more than enough to be concerned about. A policy of near-zero short-term interest rates continues to distort reality with unknown but worrisome long-term consequences. Even as the Fed begins to taper, the announced plan is so mild and contingent – one pundit called it “taper-lite” – that we can draw no legitimate conclusions about the Fed’s ability to end QE without severe consequences. Fiscal stimulus, in the form of sizable deficits, has propped up the consumer, thereby inflating corporate revenues and earnings. But what is the right multiple to pay on juiced corporate earnings? Pretty clearly, lower than otherwise. Yet Robert Schiller’s cyclically adjusted P/E valuation is over 25, a level exceeded only three times before – prior to the 1929, 2000 and 2007 market crashes. Indeed, on almost any metric, the U.S. equity market is historically quite expensive. A skeptic would have to be blind not to see bubbles inflating in junk bond issuance, credit quality, and yields, not to mention the nosebleed stock market valuations of fashionable companies like Netflix and Tesla. The overall picture is one of growing risk and inadequate potential return almost everywhere one looks. There is a growing gap between the financial markets and the real economy. Flash-Mob Speculation When it comes to stock market speculation, it’s never hard to build a “coalition of willing.” A flash mob of day traders, momentum investors, and the usual hot money crowd drove one of the best years in decades for U.S., Japanese, and European equities. Even with the ranks of the unemployed and underemployed still bloated and the economy barely improved from a year ago, the S&P 500, Dow Jones Industrial Average, and Russell 2000 regularly posted new record highs (45 for the S&P, 52 for the Dow, and 66 for the Russell) while gaining a remarkable 32.4%, 29.7%, and 38.8% including dividend reinvestment, respectively, in 2013. It was the best year for the S&P 500 since 1997... In the closing weeks of 2013, it was as if the strong gravitational pull of valuation had been temporarily suspended and stock prices had been launched by a booster rocket, allowing them to reach escape velocity. As with bull markets past, favored stocks started to become unmoored and unbounded. Speculative Froth and Dot-Com 2.0 Whether you see today’s investment glass as half full or half empty depends on your age and personality type, as well as your “lifetime” of experiences in the markets and how you interpret them. Our assessment is that the Fed’s continuing stimulus and suppression of volatility has triggered a resurgence of speculative froth. Margin debt measured as a percentage of GDP recently neared an all-time high. IPO activity in 2013 was greater than it has been in years, with 230 offerings taking place, 59% more than last year and approaching 2007’s record of 288 transactions. Twitter, for example, surged from $26 to almost $45 on day one, and closed the year around $64. It was priced, after all, at only twenty times its projected 2015 revenue. One analyst suggests the profitless company might achieve $50 million of “adjusted” cash earnings this year, giving it a P/E of over 500. Some hedge and mutual funds are again investing in late-stage, pre-IPO financing rounds for hot Internet companies at valuations that only seem reasonable if the companies go public, soon, and at astronomical prices. Amazon.com, with a market cap of $180 billion, trades at about 15 times estimated 2013 earnings, Netflix at about 181 times. Tesla Motors’ P/E is about 279; LinkedIn’s is 145. Even though Netflix now carries some original programming, we’re pretty sure we’ve seen this movie before. Some 23-year-olds have sold their startup internet companies for hundreds of millions of dollars, while the profitless privately-held Snapchat has turned down a $3 billion buyout offer. In Silicon Valley, it seems that business plans – a narrative of how one intends to make money – are once again far more valuable than many actual businesses engaged in real world commerce and whose revenues exceed expenses. Ominous Signs In an ominous sign, a recent survey of U.S. investment newsletters by Investors Intelligence found the lowest proportion of bears since the ill-fated year of 1987. A paucity of bears is one of the most reliable reverse indicators of market psychology. In the financial world, things are hunky dory; in the real world, not so much. Is the feel-good upward march of people’s 401(k)s, mutual fund balances, CNBC hype, and hedge fund bonuses eroding the objectivity of their assessments of the real world? We can say with some conviction that it almost always does. Frankly, wouldn’t it be easier if the Fed would just announce the proper level for the S&P, and spare us all the policy announcements and market gyrations? Europe Isn't Fixed Europe isn’t fixed either, but you wouldn’t be able to tell that from investor sentiment. One sell-side analyst recently declared that ‘the recovery is here,’ a sharp reversal from his view in July 2012 that Greece had a 90% chance of leaving the Euro by the end of 2013. Greek government bond prices have nearly quintupled in price from the mid-2012 lows. Yet, despite six years of painful structural adjustments, Greece’s government debt-to-GDP ratio currently stands at 157%, up from 105% in 2008. Germany’s own government debt-to-GDP ratio stands at 81%, up from 65% in 2008. That doesn’t look fixed to us. The EU credit rating was recently reduced by S&P. European unemployment remains stubbornly above 12%. Not fixed. Various other risks lurk on the periphery: bank deposits remain frozen in Cyprus, Catalonia seems to be forging ahead with an independence referendum in 2014, and social unrest continues to escalate in Ukraine and Turkey. And all this in a region that remains saddled with deep structural imbalances. As Angela Merkel recently noted, Europe has 7% of the world’s population, 25% of its output, and 50% of its social spending. Again, not fixed. Bitcoin And Gold Only in a bull market could an online “currency” dubbed bitcoin surge 100-fold in one year, as it did in 2013. The phenomenon spurred The Wall Street Journal to call it a “cryptocurrency” craze, with dozens of entrants. Bitcoin now has an estimated market “value” in excess of $6 billion, leaving alphacoin, fastcoin, gridcoin, peercoin, and Zeuscoin in its wake. Now most sell-side firms are rushing to provide research on this latest fad, while “bitcoin funds” are being formed. Recent recruitment e-mails to staff such a platform reassure that even though experience is preferred, it is not required. While bitcoin is yet another bandwagon we are happy to let pass us by, the thinking behind cryptocurrencies may contain a kernel of rationality. If paper currencies – dollars and yen – can be printed in essentially unlimited volumes, and just as with all currencies are only worth what recipients on any given day will exchange in goods or services, then what makes them any better than the “crypto” kind of money? The dollars and yen are, of course, legal tender issued by governments, but in an era in which governments are neither popular nor trusted, that is not necessarily a big plus. Gold, at least, has been regarded as “money,” for thousands of years, and it is relatively stable and widely accepted store of value and medium of exchange. It’s a well-known monetary “brand.” It doesn’t exist only (or at all) in cyberspace, and it cannot be printed on the whim of authorities. Ironically and perplexingly, while gold, the hard money alternative to the printing press kind of money, dropped 28% in 2013, the untested and highly speculative bitcoin went completely through the roof. "The Truman Show" Market Welcome to “The Truman Show” market. In the 1998 film by that name, actor Jim Carrey is ignorant of the fact that his life is a hugely popular reality show. His every action, unbeknownst to him, is manipulated while being broadcast to millions of TV viewers worldwide. He seemingly lives in an idyllic seaside community where the manicured lawns are always green and the citizens are always happy. These people are, of course, actors. The world Truman inhabits turns out to be phony: a gigantic sound stage created for a manufactured “reality.” As Truman starts to unravel the truth, his anger erupts and chaos ensues. Ben Bernanke and Mario Draghi, as in the movie, are the “creators” who have manufactured a similarly idyllic, if artificial, environment for today’s investors. They were the executive producers of “The Truman Show” of 2013. A global audience sat in rapt attention before this wildly popular production. Given the U.S. stock market’s continuing upsurge, Bernanke is almost certain to snag yet another People’s Choice Award for this psychological “thriller.” Even in “The Truman Show,” life was not as good as this for investors. But there is one fly in the ointment: in Bernanke’s production, all the Trumans – the economists, fund managers, traders, market pundits – know at some level that the environment in which they operate is not what it seems on the surface. The Fed and the Treasury openly discuss the aim of their policies: to manipulate financial markets higher and to generate reported economic “growth” and a “wealth effect.” Inside the giant Plexiglas dome of modern capital markets, just about everyone is happy, the few doubters are mocked and jeered, bad news is increasingly ignored, and markets go asymptotic. The longer QE continues, the more bloated the Fed balance sheet and the greater the risk from any unwinding. The artificiality of today’s markets is pure Truman Show. According to the Wall Street Journal (12/20/13), the Federal Reserve purchased about 90% of all the eligible mortgage bonds issued in November. Like a few glasses of wine with dinner, the usual short-term performance pressures on most investors to keep up with the market serve to dull their senses, which makes it a bit easier to forget that they are being manipulated. But what is fake cannot be made real. As Jim Grant recently noted on CNBC, the problem is that “the Fed can change how things look, it cannot change what things are.” According to John Phelan, a fellow at the Cobden Centre in the U.K., “the Federal Reserve has become an enabler of the financial havoc it was designed (a century ago) to prevent.” Every Truman under Bernanke’s dome knows the environment is phony. But the zeitgeist so damn pleasant, the days so resplendent, the mood so euphoric, the returns so irresistible, that no one wants it to end, and no one wants to exit the dome until they’re sure everyone else won’t stay on forever. A marketplace of knowing Trumans seems even more unstable than the movie sound stage character slowly awakening to reality. Can the clued-in Trumans be counted on to maintain their complicity or will they go off-script? Will Fed actions reliably be met with the desired response? Will the program remain popular? Could “The Truman Show” be running out of material? After all, even Seinfeld ended. Someday, the Fed’s show will be off the air and new programming will take its place. And people will debate just how good it really was. When the show ends, those self-deluded Trumans will be mad as hell and probably broke as well. Hopefully there will be no sequels. Someday... Someday, financial markets will again decline. Someday, rising stock and bond markets will no longer be government policy – maybe not today or tomorrow, but someday. Someday, QE will end and money won’t be free. Someday, corporate failure will be permitted. Someday, the economy will turn down again, and someday, somewhere, somehow, investors will lose money and once again come to favor capital preservation over speculation. Someday, interest rates will be higher, bond prices lower, and the prospective return from owning fixed-income instruments will again be roughly commensurate with the risk. Someday, professional investors will come to work and fear will have come to the markets and that fear will spread like wildfire. The news flow will be bad, and the markets will be tumbling. ... Six years ago, many investors were way out over their skis. Giant financial institutions were brought to their knees... The survivors pledged to themselves that they would forever be more careful, less greedy, less short-term oriented. But here we are again, mired in a euphoric environment in which some securities have risen in price beyond all reason, where leverage is returning to rainy markets and asset classes, and where caution seems radical and risk-taking the prudent course. Not surprisingly, lessons learned in 2008 were only learned temporarily. These are the inevitable cycles of greed and fear, of peaks and troughs. Can we say when it will end? No. Can we say that it will end? Yes. And when it ends and the trend reverses, here is what we can say for sure. Few will be ready. Few will be prepared. By Greg Robb

Market Pulse March 5, 2014 WASHINGTON (MarketWatch) -- Richard Fisher, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, on Wednesday said he was concerned about "eye-popping levels" of some stock market metrics, and said the central bank has to monitor the signs carefully to make sure another bubble isn't forming. In his speech in Mexico City, Fisher said some indicators like the price-to-projected forward earnings, price-to-sales ratios and market capitalization as a percentage of GDP, are at levels not seen since the dot-com boom of the late 1990s. He noted that margin debt is pushing up against all-time records. "We must monitor these indicators very carefully so as to ensure that the ghost of 'irrational exuberance' does not haunt us again," Fisher said. While a few Fed officials have mentioned unease about stock prices, Fisher's comments are the most pointed to date. Fisher did not spare the bond market, saying that narrow spreads between corporate and Treasury debt "reflect lower risk premia on top of already abnormally low nominal yields." Fisher is a voting member of the Fed's monetary policy committee this year. He has been a strong opponent of the Fed's latest round of asset purchases. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed