Excerpted from: That Was The Weak That Worked: Part I By Grant Williams Things That Make You Go Hmmm... December 30, 2013 The chart below, deflating the S&P 500 by the ongoing QE experiment, which I included a few weeks ago courtesy of Raoul Pal & Remi Tetot of Global Macro Investor, strips away the effect of the Fed's pumping and lays bare the market's real performance. It's one of the best charts I've seen this year, and it speaks volumes.  Equity prices used to be a reflection of the strength of the underlying economy — after all, the component pieces of benchmark indices were functioning companies that existed in the real world where they need to manufacture something and sell it to a buyer in order to stay in business and make a profit. So how have companies and the economy they constituted done in 2013? Well, the companies themselves have done incredibly well at tightening their own belts and squeezing every last drop of juice out of the lemons they've been handed. In fact, corporate profits have never been higher; and as a percentage of GDP they have scaled new and almost unimaginable heights, as the chart to the right demonstrates: But under the surface and in the wider economy, the story is very different, indeed, as the mountain of cash on corporate balance sheets has led to an avalanche of buybacks, which has in turn boosted earnings and given the impression that things are roaring, when in fact the true story is a familiar one of an increase in debt. And it's one that we saw not so very long ago: (Karl Denninger): The second important thing to understand is that the other claim — "record corporate cash" — is true but intentionally misleading. What's also at records is corporate debt, and what you must look at is not tangible assets (which includes cash, of course) but rather such assets less obligations, that is, debt. And when you do and compare against equity prices what do you see? This chart was bad at the end of 2012 — in bubble territory, for sure — which was a big part of why I didn't think we'd get through 2013. Well, we did — and now it's worse, because this is only updated through the end of September and of course the market has gone screaming higher in the last three months.  Very high "skew" reflects an implied probability distribution with a "fat left tail" - assigning a larger than normal probability to significantly negative outcomes. What’s notable here is that unusually large option skew approaching the 1987 crash suggested that option market participants were implicitly aware of the "too good to be true" nature of the advance, and were compensating by pricing options to better reflect the risk of a steep market drop. What’s equally notable is that the 10-day (exponential) moving average of option skewness hit the highest level in history last week. -- John Hussman, December 30, 2013 Excerpted from: Estimating the Risk of a Market Crash John P. Hussman, Ph.D. December 30, 2013 “We thought it was the eighth inning, and it was the ninth. I did not think it would go down 33 percent in 15 days.” - Stanley Druckenmiller In April 2000, Stanley Druckenmiller, who managed the phenomenally successful Quantum fund for George Soros, called it quits – saying “I overplayed my hand” in technology stocks. The Nasdaq composite had suffered the first blow of what was to become a much deeper loss, with the index losing an additional 70% by 2002 low. Still, getting out was a good idea in hindsight. With one of the best records in the industry, Druckenmiller has expressed increasing concerns recently that “all the lobsters are in the pot.” A few weeks ago, he said of equities that he holds “the smallest positions I’ve had,” and warned “a necessary condition for a financial crisis, in my opinion, is too loose monetary policy that encourages people to take undue risk.” Floyd Norris of the New York Times reported in 2000 that Druckenmiller was actually the second high-profile hedge manager to call it quits in that cycle. The first was Tiger Fund’s Julian Robertson, who had lagged the advance because he (correctly, in hindsight) viewed technology stocks as vastly overvalued. The article quoted an analyst saying “The moral of the story is that irrational markets can kill you. Julian said ‘This is irrational and I won’t play,’ and they carried him out feet first. Druckenmiller said ‘This is irrational and I will play,’ and they carried him out feet first.”  Estimating the Risk of a Market Crash In effect, if the market is adhering to a “bubble” trajectory, we should not be surprised by a phase of persistent advances toward the end, followed ultimately by a sharp decline that erases a significant amount of prior gains in one fell swoop. This is what I’ve often described as “unpleasant skewness,” and is unpleasant precisely because it has historically emerged in conditions that we identify as “overvalued, overbought, and overbullish.” These conditions are often – at least temporarily – associated with persistent further advances to successive marginal new highs, followed by a steep loss. With regard to present market conditions, the increasingly severe overvalued, overbought, overbullish features of the market here are coupled with soaring margin debt as speculators accumulate stock with borrowed money; record issuance of low-grade “covenant lite” debt; heavy issuance of new stocks – particularly characterized by speculative narratives; and a price trajectory that is eerily well-described by the mathematics of a “log-periodic bubble” that economist Didier Sornette described a decade ago, and has regularly been observed in financial bubbles across asset classes and countries across history. Interestingly, the no-arbitrage condition also gives us the mathematical tool to estimate the “hazard rate” or crash probability over any finite horizon. Our estimate is that this probability is soaring here. As I noted again approaching the 2007 market peak, the need to wait for some observable “catalyst” to justify a defensive stance is reminiscent of other awful consequences of overvalued, overbought, overbullish, rising-yield syndromes, including the 1987 crash: “Investors could find no news to explain the crash in that instance, except an unusually large trade gap with Germany, so they continued to fear that particular piece of data. But day-to-day news events rarely ‘cause’ large market movements… Once certain extremes are clear in the data, the main cause of a market plunge is usually the inevitability of a market plunge. That's the reason we sometimes have to maintain defensive positions in the face of seemingly good short-term market behavior.”

Sornette described this same regularity a decade ago: “The underlying cause of the crash will be found in the preceding months and years, in the progressively increasing build-up of market cooperativity, or effective interactions between investors, often translated into accelerating ascent of the market price. According to this “critical” point of view, the specific manner by which prices collapsed is not the most important problem: a crash occurs because the market has entered an unstable phase and any small disturbance or process may have triggered the instability. The collapse is fundamentally due to the unstable position; the instantaneous cause of the collapse is secondary. Essentially, anything would work once the system is ripe… a crash has fundamentally endogenous, or internal origin.” My opinion is that present circumstances will not end well, and that a very finite number of speculators will be able to exit with their paper gains successfully...My guess is that the present speculative advance may have a few percent to run – I’ll be particularly concerned if the market does so in a rapid, uncorrected manner in the next couple of weeks, which could suggest crash probabilities approaching 100% based on the sort of analysis above.  Excerpted from: The Diva is Already Singing John P. Hussman, Ph.D. December 23, 2013 Bubble Update Regardless of last week’s slight tapering of the Federal Reserve’s policy of quantitative easing, speculators appear intent on completing the same bubble pattern that has attended a score of previous financial bubbles in equity markets, commodities, and other assets throughout history and across the globe. The chart below provides some indication of our broader concerns here. The blue lines indicate the points of similarly overvalued, overbought, overbullish, rising-yield conditions across history (specific definitions and variants of this syndrome can be found in numerous prior weekly comments). Sentiment figures prior to the 1960’s are imputed based on the relationship between sentiment and the extent and volatility of prior market fluctuations, which largely drive that data. Most of the prior instances of this syndrome were not as extreme as at present (for example, valuations are now about 35% above the overvaluation threshold for other instances, overbought conditions are more extended here, and with 58% bulls and only 14% bears, current sentiment is also far more extreme than necessary). So we can certainly tighten up the criteria to exclude some of these instances, but it’s fair to say that present conditions are among the most extreme on record. This chart also provides some indication of our more recent frustration, as even this variant of “overvalued, overbought, overbullish, rising-yield” conditions emerged as early as February of this year and has appeared several times in the past year without event. My view remains that this does not likely reflect a permanent change in market dynamics – only a temporary deferral of what we can expect to be quite negative consequences for the market over the completion of this cycle.  Narrowing our focus to the present advance, what concerns us isn’t simply the parabolic advance featuring increasingly immediate impulses to buy every dip – which is how we characterize the psychology behind log-periodic bubbles (described by Didier Sornette in Why Markets Crash). It’s that this parabola is attended by so many additional and historically regular hallmarks of late-phase speculative advances. Aside from strenuously overvalued, overbought, overbullish, rising-yield conditions, speculators are using record amounts of borrowed money to speculate in equities, with NYSE margin debt now close to 2.5% of GDP. This is a level seen only twice in history, briefly at the 2000 and 2007 market peaks. Margin debt is now at an amount equal to 26% of all commercial and industrial loans in the U.S. banking system. Meanwhile, we are again hearing chatter that the Federal Reserve has placed a “put option” or a “floor” under the stock market. As I observed at the 2007 peak, before the market plunged 55%, “Speculators hoping for a ‘Bernanke put’ to save their assets are likely to discover – too late – that the strike price is way out of the money.” The following chart is not a forecast, and certainly not something to be relied upon. It does, however, provide an indication of how Sornette-type bubbles have ended in numerous speculative episodes in history, in equities, commodities, and other assets, both in the U.S. and abroad. We are already well within the window of a “finite-time singularity” – the endpoint of such a bubble, but it is a feature of parabolas that small changes in the endpoint can significantly change the final value. The full litany of present conditions could almost be drawn from a textbook of pre-crash speculative advances. We observe the lowest bearish sentiment in over a quarter century, speculation in equities using record levels of margin debt, depressed mutual fund cash levels, heavy initial public offerings of stock, record issuance of low-grade “covenant lite” debt, strikingly rich valuations on a wide range of measures that closely correlate with subsequent market returns, faith that the Fed has put a “floor” under the market (oddly the same faith that investors relied on in 2007), and the proliferation of “this time is different” adjustments to historically reliable investment measures. Even at 1818 on the S&P 500, we have to allow for the possibility that speculators have not entirely had their fill. In my view, the proper response is to maintain a historically-informed discipline, but with limited concessions (very small call option positions have a useful contingent profile) to at least reduce the temptation to capitulate out of undisciplined, price-driven frustration. Regardless of whether the market maintains its fidelity to a “log-periodic bubble,” we’ll continue to align our position with the expected return/risk profile as it shifts over time. That said, the “increasingly immediate impulses to buy every dip” that characterize market bubbles have now become so urgent that we have to allow for these waves to compress to a near-vertical finale. The present log-periodic bubble suggests that this speculative frenzy may very well have less than 5% to run between current levels and the third market collapse in just over a decade. As I advised in 2008 just before the market collapsed, be very alert to increasing volatility at 10-minute intervals. The bell has already rung. The diva is already singing. The only question is precisely how long they hold the note.

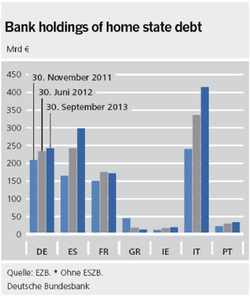

Excerpted from: The Monster That Is Europe By John Mauldin | Dec 16, 2013 Where There Is One Cockroach… One of the rules of investing is that there is never just one cockroach. S&P noted this fall that Europe's banks still had a funding gap of €1.3 trillion at the end of 2012; and most of this has yet to be funded or loan-loss provisions made, so the financial system is not out of the woods by any means – no matter what the complacency of consensus indicates. Shipping is just one business segment of German banks, but given the present economics of shipping, losses are likely to be much higher than forecast. And if the banks have hidden the actual extent of their losses in those other segments, as they appear to have done in the shipping arena? Inquiring minds wonder about problems in the other business groups of these banks. The shortfalls could be much larger than we know. Bad debts in Spain keep hitting a fresh record each month, and I have written about the problems in French and Italian banks. There seems to be a Europe-wide problem with bank debt . That might explain the worry that Mario Draghi expressed last month, which we'll turn to in a bit. The problem is not simply that European banks are inadequately capitalized. A committed ECB, given the freedom to act by Germany et al., could overcome that problem, though not without repercussions. The additional problem causing the current growth malaise and an unprecedented wave of high unemployment in the "developed" global economy is the rather perverse disincentives in effect for the banking industry in Europe. These disincentives have resulted in capital for businesses drying up. The ECB has actually provided huge amounts of capital for banks in an effort to get them to lend to businesses. But faced with regulatory risks and the significant requirement for increased reserve capital imposed by Basel III, the banks have taken the cheap money and bought their national government bonds, because the spreads are so high and the reserve capital required for making a sovereign loan is still bupkis (a technical banking term pertaining to European sovereign loan-loss provisions to insolvent governments). Italy has now seen its debt-to-GDP ratio rise from 119% to 133% even as Italian banks buy huge amounts of debt, mainly from non-Italian banks. Ditto for Spain, Portugal et al. The chart below illustrates the issue. Thus there is a massive shortage of financing available for solid medium and small businesses. Further, regulators are now seriously thinking about not only applying additional controls on the capital that is loaned to banks, but also forcibly converting junior and senior loans to capital, aggressively hurting those who are lending to banks. So much so that ECB president Mario Draghi recently wrote a private letter (which of course did not remain private) to the various authorities imploring them to stop their efforts. The problem is, the authorities see the problems correctly and are trying to force recapitalizations at the expense of the private sector, which is the right thing to do. Taxpayer funding of private banks should not occur except under extreme circumstances and then only "with extreme prejudice," which means wiping out the private shareholders. But if potential new investors think their loans are at risk for large haircuts, then the market for bank debt will dry up again. Didn't we watch that movie in 2008-09? The wording in Mario's letter asserts that punitive haircuts (the easy thing for a regulator to impose) and a full-blown assault on junior bank debt could lead to a "flight of investors out of the European banking market." There are no easy solutions for an overleveraged, out-of-control banking system. Except the one proposed by Irving Fisher late in his life, after he had witnessed the debacle of the Great Depression. His basic recommendation was to not allow the leveraging to begin with. It is too late to do anything after the fact except clean up the mess. Draghi says the ECB's bank stress tests early next year will degenerate into a fiasco or worse unless EU leaders put in place "credible public backstops" to cover cases where there is not enough money from private investors to recapitalize the banks. The whole botched structure "may very well destroy the very confidence in euro area banks which we all intend to restore." (The Telegraph) Draghi is clearly committed to providing as much central bank financing as he possibly can to keep the system liquid. (You do not write such an impassioned letter if you have no concerns.) As some have noted, the German Bundesbank has hinted that investors might see their capital impaired before the government has to admit to taxpayers the true cost of holding the eurozone together – no matter what the cost turns out to be to the system in general if investors take the hit. Then again, maybe the Bundesbank will feel that they can exert their will only in the midst of a crisis. If so, they may very well help precipitate one. I think a major risk to the current status quo is another European sovereign debt and banking crisis in a world where risky leverage is once again mounting in the quest for elusive yield. The uncertainty we face, no matter what the consensus view, is troubling to your humble analyst. How should we then invest? The brilliant and always must-read Howard Marks of Oaktree summed the situation up nicely in his latest letter. (According to Business Insider, "[Howard's] letters read like Michael Lewis ghostwriting for Warren Buffett: insightful, direct, homespun, expert and sharply pointed. Their quality and insight have gained them a devoted readership among value investors.") I quote a little liberally, because summing up his already succinct prose loses a lot in translation. (Note: emphasis in the original): As I've said before, most people are aware of these uncertainties. Unlike the smugness, complacency and obliviousness of the pre-crisis years, today few people are as confident as they used to be about their ability to predict the future, or as certain that it will be rosy. Nevertheless, many investors are accepting (or maybe pursuing) increased risk. As I close on a beautiful Sunday afternoon, the following darkish note hit my inbox, and I think it's the perfect thing to wrap up with. It seems the world's largest investor, BlackRock (at $4.1 trillion), suggests in their yearend letter that investors should be prepared to pull out of global markets at signs of serious trouble, but should try to squeeze out more returns in the process. Their advice should make you think about your own investment decision process. "Beware of traffic jams: easy to get into, hard to get out of," they write. They highlight the risks that are posed by central banks (shades of Code Red!): "The banking system in the eurozone periphery is under water, with a non-performing loan pile of €1.5 trillion to €2 trillion. Germany and other core countries are unlikely to pick up the tab. Eastern Europe could become the epicentre of funding risk in 2014 due to big refinancings," it said. BlackRock said the eurozone is "stuck in a monetary corset", failing to generate the nominal GDP growth of 3pc to 5pc needed for economies to outgrow their debt burdens. It's Quiet Out There. Maybe Too Quiet…

My porous old memory can't quiet place the source, but I think it might have been an old John Wayne movie, where the sergeant says, "It's quiet out there," and Wayne answers, "Maybe it's too quiet" – just before all the Indians in the world swoop onto the camp out of the darkness. The consensus seems to be saying it is quiet out there. And I can't hear anything, either. And that makes me even more nervous. Be careful out there. By Mark Spitznagel | Founder and CIO of Universa Investments LP

CNBC Monday, 23 Dec 2013 One hundred years ago, on Dec. 23, 1913, the Federal Reserve Act was signed into law, giving the United States exactly what it didn't need: a central bank. Americans had gone without one since the 1836 expiration of the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, which Andrew Jackson famously refused to renew. Not to be a party pooper, but as this dubious centennial is observed, we should ask ourselves: Has the Fed been friend or foe to growth and prosperity? According to the standard historical narrative, the U.S. learned a painful lesson in the Panic of 1907 that a "lender of last resort" was necessary lest the financial sector be at the mercy of private capitalists such as J.P. Morgan. A central bank—the Federal Reserve—was supposed to provide an "elastic currency" that would expand and contract with the needs of trade, and that could rescue solvent but illiquid firms by providing liquidity when other institutions couldn't or wouldn't. If that's the case, then the Fed has obviously failed in its mission of preventing crippling financial panics. The early years of the Great Depression—starting with a stock market crash that arrived a full 15 years after the Fed opened its doors—saw far more turmoil than anything in the pre-Fed days, with some 4,000 commercial banks failing in 1933 alone. A typical defense acknowledges that the Fed botched its job during the Great Depression, but once the wise regulations of the New Deal were put into place and academic economists realized just what had gone wrong, it was relatively smooth sailing from that point forward. It would be silly, these apologists argue, to question the advantage of central banking now that we have learned so many painful lessons, lessons that Fed officials take into account when making policy decisions. What about the excruciating pain of the recent past, dubbed the Great Recession of 2008-09? In the five years from 2008-12 almost 500 banks have failed. What would history need to look like for people to agree that the Fed has not done its job? But wait! The Fed is necessary to the promotion of stable economic growth—or so convention wisdom says. The idea here is that without a central bank, the economy would be plagued by wildly oscillating business cycles. The only hope is a "countercyclical policy" of raising interest rates to cool an overheating boom, and then slashing rates to turn up the flame during a bust. In actuality, the Fed's modus operandi has been to trick capitalists into doing things that are not aligned with economic reality. For example, the Fed creates the illusion, through artificially low interest rates, that there is both higher savings and higher consumption, and thus all assets should be worth more (making their holders invest and spend more—can you say "bubble?"). The perpetuation of this trickery only delays the market's eventual, and often precipitous, return to reality. Many economists now recognize that the massive housing bubble of the early and mid-2000s was caused by the artificially low interest rate approach of the Greenspan Fed, enacted in response to the dot-com crash (itself the ostensible result of artificially low rates). At the time, this was viewed as textbook pro-growth monetary policy; the economy (allegedly) needed a shot in the arm to get consumers and businesses spending again, especially after the 9/11 attacks. It appears those "textbooks" are wrong. Economists Selgin, Lastrapes and White analyzed the Fed's record and found that even focusing on the post-World War II era, it is not clear that the Fed has provided more economic stability compared with the pre-Fed regime that was characterized by the National Banking system. The authors concluded that "the need for a systematic exploration of alternatives to the established monetary system is as pressing today as it was a century ago." In other sectors, we don't normally defer to a committee of a dozen experts to set prices. Yet this is what the Fed does with its "open market committee" that routinely sets a target for the "federal funds rate" as well as other objectives. If we all agree that central planning and price-fixing don't work for computers and oil, why would we expect it to bring us stability in money and banking? On this, the 100th birthday of the Fed, it's time to ask ourselves: Wouldn't we be better off without a central bank? A timely review of the Fed and its policies. The first part of the film focuses on the Fed's history since its creation 100 years ago. Of particular importance is how the Fed changed under Greenspan who actively used monetary policy to fine tune the economy. This is further developed in the second part of the film which focuses on Bernanke and his penchant for academically-derived ideas on monetary policy around money printing (QE) and zero interest rates (ZIRP) - a grand experiment.

From the Publisher: Money For Nothing: Inside The Federal Reserve is an independent, non partisan documentary film that examines America's central bank in a critical, yet balanced way. Narrated by the acclaimed actor Liev Schreiber, and featuring interviews with Paul Volcker, Janet Yellen, Jeremy Grantham and many of the world's best financial minds, Money For Nothing is the first film ever to take viewers inside the world's most powerful financial institution. Click to access the website to purchase the film By Janet Tavakoli

Hunffington Post 17 December 2013 Excerpt: ----- Kyle Bass, founder of Hayman Capital Management, announced during his March 2013 talk to the Chicago Booth's Global Markets Initiative that he is bearish on Japan and has engaged in trades that will pay off in an extreme scenario:

Shortly after Bass put on his trade, bank traders asked the hedge fund manager to close out his position. They explained they ran a new model with better stress tests, and the trades were riskier than they first thought. Bass declined, even though he could have made a quick profit. He'd rather harpoon a whale. ---- The rest of the article is well worth the read (click here to access full article). |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed