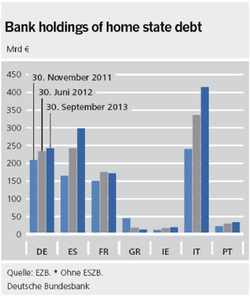

Excerpted from: The Monster That Is Europe By John Mauldin | Dec 16, 2013 Where There Is One Cockroach… One of the rules of investing is that there is never just one cockroach. S&P noted this fall that Europe's banks still had a funding gap of €1.3 trillion at the end of 2012; and most of this has yet to be funded or loan-loss provisions made, so the financial system is not out of the woods by any means – no matter what the complacency of consensus indicates. Shipping is just one business segment of German banks, but given the present economics of shipping, losses are likely to be much higher than forecast. And if the banks have hidden the actual extent of their losses in those other segments, as they appear to have done in the shipping arena? Inquiring minds wonder about problems in the other business groups of these banks. The shortfalls could be much larger than we know. Bad debts in Spain keep hitting a fresh record each month, and I have written about the problems in French and Italian banks. There seems to be a Europe-wide problem with bank debt . That might explain the worry that Mario Draghi expressed last month, which we'll turn to in a bit. The problem is not simply that European banks are inadequately capitalized. A committed ECB, given the freedom to act by Germany et al., could overcome that problem, though not without repercussions. The additional problem causing the current growth malaise and an unprecedented wave of high unemployment in the "developed" global economy is the rather perverse disincentives in effect for the banking industry in Europe. These disincentives have resulted in capital for businesses drying up. The ECB has actually provided huge amounts of capital for banks in an effort to get them to lend to businesses. But faced with regulatory risks and the significant requirement for increased reserve capital imposed by Basel III, the banks have taken the cheap money and bought their national government bonds, because the spreads are so high and the reserve capital required for making a sovereign loan is still bupkis (a technical banking term pertaining to European sovereign loan-loss provisions to insolvent governments). Italy has now seen its debt-to-GDP ratio rise from 119% to 133% even as Italian banks buy huge amounts of debt, mainly from non-Italian banks. Ditto for Spain, Portugal et al. The chart below illustrates the issue. Thus there is a massive shortage of financing available for solid medium and small businesses. Further, regulators are now seriously thinking about not only applying additional controls on the capital that is loaned to banks, but also forcibly converting junior and senior loans to capital, aggressively hurting those who are lending to banks. So much so that ECB president Mario Draghi recently wrote a private letter (which of course did not remain private) to the various authorities imploring them to stop their efforts. The problem is, the authorities see the problems correctly and are trying to force recapitalizations at the expense of the private sector, which is the right thing to do. Taxpayer funding of private banks should not occur except under extreme circumstances and then only "with extreme prejudice," which means wiping out the private shareholders. But if potential new investors think their loans are at risk for large haircuts, then the market for bank debt will dry up again. Didn't we watch that movie in 2008-09? The wording in Mario's letter asserts that punitive haircuts (the easy thing for a regulator to impose) and a full-blown assault on junior bank debt could lead to a "flight of investors out of the European banking market." There are no easy solutions for an overleveraged, out-of-control banking system. Except the one proposed by Irving Fisher late in his life, after he had witnessed the debacle of the Great Depression. His basic recommendation was to not allow the leveraging to begin with. It is too late to do anything after the fact except clean up the mess. Draghi says the ECB's bank stress tests early next year will degenerate into a fiasco or worse unless EU leaders put in place "credible public backstops" to cover cases where there is not enough money from private investors to recapitalize the banks. The whole botched structure "may very well destroy the very confidence in euro area banks which we all intend to restore." (The Telegraph) Draghi is clearly committed to providing as much central bank financing as he possibly can to keep the system liquid. (You do not write such an impassioned letter if you have no concerns.) As some have noted, the German Bundesbank has hinted that investors might see their capital impaired before the government has to admit to taxpayers the true cost of holding the eurozone together – no matter what the cost turns out to be to the system in general if investors take the hit. Then again, maybe the Bundesbank will feel that they can exert their will only in the midst of a crisis. If so, they may very well help precipitate one. I think a major risk to the current status quo is another European sovereign debt and banking crisis in a world where risky leverage is once again mounting in the quest for elusive yield. The uncertainty we face, no matter what the consensus view, is troubling to your humble analyst. How should we then invest? The brilliant and always must-read Howard Marks of Oaktree summed the situation up nicely in his latest letter. (According to Business Insider, "[Howard's] letters read like Michael Lewis ghostwriting for Warren Buffett: insightful, direct, homespun, expert and sharply pointed. Their quality and insight have gained them a devoted readership among value investors.") I quote a little liberally, because summing up his already succinct prose loses a lot in translation. (Note: emphasis in the original): As I've said before, most people are aware of these uncertainties. Unlike the smugness, complacency and obliviousness of the pre-crisis years, today few people are as confident as they used to be about their ability to predict the future, or as certain that it will be rosy. Nevertheless, many investors are accepting (or maybe pursuing) increased risk. As I close on a beautiful Sunday afternoon, the following darkish note hit my inbox, and I think it's the perfect thing to wrap up with. It seems the world's largest investor, BlackRock (at $4.1 trillion), suggests in their yearend letter that investors should be prepared to pull out of global markets at signs of serious trouble, but should try to squeeze out more returns in the process. Their advice should make you think about your own investment decision process. "Beware of traffic jams: easy to get into, hard to get out of," they write. They highlight the risks that are posed by central banks (shades of Code Red!): "The banking system in the eurozone periphery is under water, with a non-performing loan pile of €1.5 trillion to €2 trillion. Germany and other core countries are unlikely to pick up the tab. Eastern Europe could become the epicentre of funding risk in 2014 due to big refinancings," it said. BlackRock said the eurozone is "stuck in a monetary corset", failing to generate the nominal GDP growth of 3pc to 5pc needed for economies to outgrow their debt burdens. It's Quiet Out There. Maybe Too Quiet…

My porous old memory can't quiet place the source, but I think it might have been an old John Wayne movie, where the sergeant says, "It's quiet out there," and Wayne answers, "Maybe it's too quiet" – just before all the Indians in the world swoop onto the camp out of the darkness. The consensus seems to be saying it is quiet out there. And I can't hear anything, either. And that makes me even more nervous. Be careful out there. Comments are closed.

|

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed