|

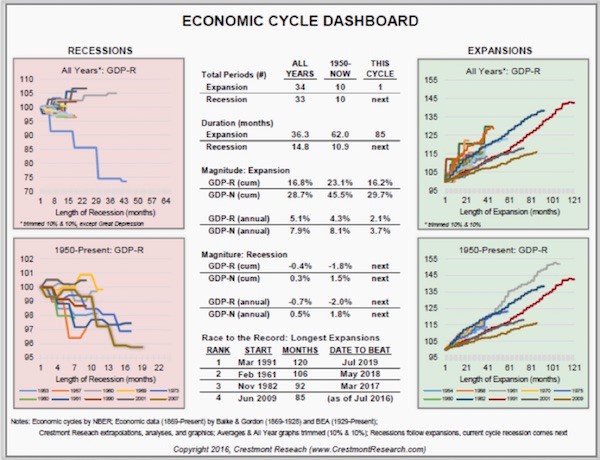

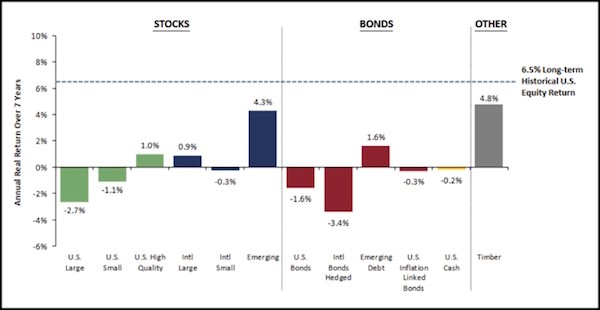

by John Mauldin July 16, 2016 The Age of No Returns The enemy is coming. Having absorbed Japan to the west and Europe to the east, negative interest rates now threaten North America from both directions. The vast oceans that protect us from invasions won’t help this time. Someday I want to get someone to count the number of times I’ve mentioned central bank chiefs by name in this newsletter since I first began writing in 2000, and we should graph the mentions by month. I suspect we’ll find that the number spiked higher in 2007 and has remained at a high plateau ever since – if it has not climbed even higher. That’s our problem in a nutshell. We shouldn’t have to talk about central banks and their leaders every time we discuss the economy. Monetary policy is but one factor in the grand economic equation and should certainly not be the most important one. Yet the Fed and its fellow central banks have been hogging center stage for nearly a decade now. That might be okay if their policies made sense, but abundant evidence says they do not. Overreliance on low interest rates to stimulate growth led our central bankers to zero interest rates. Failure of zero rates led them to negative rates. Now negative rates aren’t working, so their ploy is to go even more negative and throw massive quantitative easing and deficit financing at the balky global economy. Paul Krugman is beating the drum for more radical Keynesianism as loudly as anyone. He has a legion of followers. Unfortunately, they are in control in the halls of monetary policy power. Our central banks are one-trick ponies. They do their tricks well, but no one is applauding, except the adherents of central bank philosophy. Those of us who live in the real economy are growing increasingly restive. Today we’ll look at a few of the big problems that the Fed and its ilk are creating. As you’ll see, I think we are close to the point in the US where a significant course change might help, because our fate is increasingly locked in. I believe Europe and Japan have passed the point of no return. That means we should shift our thinking toward defensive measures. The Big Conundrum The immediate Brexit shock is passing, for now, but Europe is still a minefield. The Italian bank situation threatens to blow up into another angry stand-off like Greece, with much larger amounts at stake. The European Central Bank’s grand plans have not brought Southern Europe back from depression-like conditions. I cannot state this strongly enough: Italy is dramatically important, and it is on the brink of a radical break with European Union policy that will cascade into countries all over Europe and see them going their own way with regard to their banking systems. Italian politicians cannot allow Italian citizens to lose hundreds of billions, if not trillions, of euros to bank “bail-ins.” Such losses would be an utter disaster for Italy, resulting in a deflationary depression not unlike Greece’s. Of course, for the Italians to bail out their own banks, th ey will have to run their debt-to-GDP ratio up to levels that look like Greece’s. Will the ECB step in and buy Italy’s debt and keep their rates within reason? Before or after Italy violates ECB and EU policy? The Brexit vote isn’t directly connected to the banking issue, but it is still relevant. It has emboldened populist movements in other countries and forced politicians to respond. The usual Brussels delay tactics are losing their effectiveness. The associated uncertainty is showing itself in ever-lower interest rates throughout the Continent. That’s the situation to America’s east. On our western flank, Japan had national elections last weekend. Voters there do not share the anti-establishment fever that grips the rest of the developed world. They gave Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his allies a solid parliamentary majority. Japanese are either happy with the Abenomics program or see no better alternative. His expanded majority may give Abe the backing he needs to revise Japan’s constitution and its official pacifism policy. Doing so would be less a sign of nationalism than a new economic stimulus tool. Defense spending that more than doubles – as it is expected to do – will give a major boost to Japan’s shipyards, vehicle manufacturing, and electronics industries. The Bank of Japan’s negative-rate policy and gargantuan bond-buying operation will now continue full force and may even grow. Whether the program works or not is almost beside the point. It shows the government is “doing something” and suppresses the immediate symptoms of economic malaise. The Bank of Japan is the Japanese bond market. They are buying everything that comes available, and this year they will need to cough up an extra ¥40 trillion ($400 billion) just to make their purchase target, let alone increase their quantitative easing in the desperate attempt to drive up inflation. What is happening is that foreign speculators are becoming some of the largest holders of Japanese bonds, and many Japanese pension funds and other institutions are required to hold those bonds, so they aren’t selling. The irony is that the government is producing only about half the quantity of bonds the Bank of Japan wants to buy. Sometime this year the BOJ is going to have to do something differently. The question is, what? Okay, for you conspiracy theorists, please note that “Helicopter Ben” Bernanke was just in Japan and had private meetings with both Prime Minister Abe and Kuroda, who heads the Bank of Japan. Given the limited availability of bonds for the BOJ to buy, and that they’ve already bought a significant chunk of equities and other nontraditional holdings for a central bank, what are their other options? Perhaps Japan could authorize the BOJ to issue very-low-interest perpetual bonds to take on a significant portion of the Japanese debt. That option has certainly been a topic of discussion. It’s not exactly clear how you get people to give up their current debt when they don’t want to, or maybe the BOJ just forces them to swap out their old bonds for the new perpetual bonds, which would be on the balance sheet of the Bank of Japan and not counted as government debt. That’s one way to get rid of your debt problem. But that doesn’t give Abe and Kuroda the inflation they desperately want. Putting on my tinfoil hat (Zero Hedge should love this), the one country that could lead the way in actually experimenting with a big old helicopter drop of money into individual pockets is Japan. And Ben was just there… This bears watching. Okay, I am now removing my tinfoil hat. Yellen Changes the NIRP Tune I have been saying on the record for some time that I think it is really possible that the Fed will push rates below zero when the next recession arrives. I explained at length a few months ago in “The Fed Prepares to Dive.” In that regard, something important happened recently that few people noticed. I’ll review a little history in order to explain. In Congressional testimony last February, a member of Congress asked Janet Yellen if the Fed had legal authority to use negative interest rates. Her answer was this: In the spirit of prudent planning we always try to look at what options we would have available to us, either if we needed to tighten policy more rapidly than we expect or the opposite. So we would take a look at [negative rates]. The legal issues I'm not prepared to tell you have been thoroughly examined at this point. I am not aware of anything that would prevent [the Fed from taking interest rates into negative territory]. But I am saying we have not fully investigated the legal issues. So as of then, Yellen had no firm answer either way. A few weeks later she sent a letter to Rep. Brad Sherman (D-CA), who had asked what the Fed intended to do in the next recession and if it had authority to implement negative rates. She did not directly answer the legality question, but Bloomberg reported at the time (May 12) that Rep. Sherman took the response to mean that the Fed thought it had the authority. Yellen noted in the letter that negative rates elsewhere seemed to be having an effect. (I agree that they are having an effect; it’s just that I don’t think the effect is a good one.) Fast-forward a few more weeks to Yellen’s June 21 congressional appearance. She took us further down the rabbit hole, stating flatly that the Fed does have legal authority to use negative rates, but denying any intent to do so. “We don't think we are going to have to provide accommodation, and if we do, [negative rates] is not something on our list,” Yellen said. That denial came two days before the Brexit vote, which we now know from FOMC minutes had been discussed at a meeting the week earlier. But I’m more concerned about the legal authority question. If we are to believe Yellen’s sworn testimony to Congress, we know three things: 1. As of February, Yellen had not “fully investigated” the legal issues of negative rates. 2. As of May, Yellen was unwilling to state the Fed had legal authority to go negative. 3. As of June, Yellen had no doubt the Fed could legally go negative. When I wrote about this back in February, I said the Fed’s legal staff should all be disbarred if they hadn’t investigated these legal issues. Clearly they had. Bottom line: by putting the legal authority question to rest, the Fed is laying the groundwork for taking rates below zero. And I’m sure Yellen was telling the truth when she said last month that they had no such plan. Plans can change. The Fed always tells us they are data-dependent. If the data says we are in recession, I think it is very possible the Fed will turn to negative rates to boost the economy. Except, in my opinion, it won’t work. When Average Is Zero Now, I am not suggesting the Fed will push rates negative this month or even this year – but they will do it eventually. I’ll be surprised if it doesn’t happen by the end of 2018. A prime reason the next recession will be severe is that we never truly recovered from the last one. My friend Ed Easterling of Crestmont Research just updated his Economic Cycle Dashboard and sent me a personal email with some of his thoughts. Here is his chart (click on it to see a larger version). The current expansion is the fourth-longest one since 1954 but also the weakest one. Since 1950, average annual GDP growth in recovery periods has been 4.3%. This time around, average GDP growth has been only 2.1% for the seven years following the Great Recession. That means the economy has grown a mere 16% during this so-called “recovery” (a term Ed says he plans to avoid in the future). If this were an average recovery, total GDP growth would have been 34% by now instead of 16%. So it’s no wonder that wage growth, job creation, household income, and all kinds of other stats look so meager. For reasons I have outlined elsewhere and will write more about in the future, I think the next recovery will be even weaker than the current one, which is already the weakest in the last 60 years – precisely because monetary policy is hindering growth. Now combine a weak recovery with NIRP. If, in the long run, asset prices are a reflection of interest rates and economic growth, and both those are just slightly above or below zero, can we really expect stocks, commodities, and other assets to gain value? The upshot is that whatever traditional investment strategy you believe in will probably stop working soon. Ask European pension and insurance companies that are forced to try to somehow materialize returns in a non-return world of negative interest rates. All bets may be off anyway if the latest long-term return forecasts are correct. Here’s GMO’s latest 7-year asset class forecast: See that dotted line, the one that not a single asset class gets anywhere near? That’s the 6.5% long-term stock return that many supposedly wise investors tell us is reasonable to expect. GMO doesn’t think it’s reasonable at all, at least not for the next seven years.

If GMO is right – and they usually are – and you’re a devotee of any kind of passive or semi-passive asset allocation strategy, you can expect somewhere around 0% returns over the next seven years – if you’re lucky. Note also that nearly invisible -0.2% yellow bar for “U.S. Cash.” Negative multi-year real (adjusted for inflation) returns from cash? You bet. Welcome to NIRP, American-style. Would you like that with fries? The Fed’s fantasies notwithstanding, NIRP is not conducive to “normal” returns in any asset class. GMO says the best bets are emerging-market stocks and timber. Those also happen to be thin markets that everyone can’t hold at once. So, prepare to be stuck. Comments are closed.

|

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed