|

by Robin Wigglesworth and Mary Childs

Financial Times May 16, 2016 For most money managers, raking in $1bn in a day would be the pinnacle of achievement. But for Mark Spitznagel it was tied with winning three medals at the World Championship Cheese Contest. Mr Spitznagel runs Universa, a “tail risk” hedge fund that specialises in profiting from extreme market crashes. On August 24 last year — a day dubbed “Black Monday” by the Chinese media after the local stock market cratered and led declines across global equity markets — the firm rocketed 20 per cent, making its investors about $1bn. But for the former Chicago pit trader the triumphs of his Michigan goat farm at the recent cheese championship tasted just as sweet. The libertarian hedge fund manager sees a close similarity between what he is trying to achieve at Idyll Farms — which he built in 2010 with winnings from the financial crisis — and his investment strategy and deeply-held Austrian economic philosophy. “It’s all about sustainable use of resources. Modern farming has completely broken down the traditional system of agriculture. It’s become a machine. We’ve manipulated away its natural productivity and robustness, just like what we’ve done with markets,” he says. “Markets don’t have a purpose any more — they just reflect whatever central planners want them to.” Tail risk funds — often called “Black Swan” funds — seek to protect investors from losses during times of outsized market moves, often by buying cheap options protecting against seemingly unlikely scenarios, which then pay out if price swings are wide enough. While they can make money during volatile periods, the cost of paying premia for those hedges in the months and years waiting for the volatility adds up. Accepting the capital burn that most tail risk funds entail can be tricky for some investors, points out Andrew Ang, a prominent finance professor who now works at BlackRock. He therefore recommends “low-volatility” funds instead, that invest in blue-chip, defensive stocks that tend to be very resilient in times of turmoil. “If you can stomach the negative carry, by all account go for it, but a low-vol fund doesn’t have that [cost of buying expiring options],” he says Mr Spitznagel says that investors should keep allocations to their funds as a small percentage of their overall portfolio, and another person familiar with the matter said Universa investors should expect to lose 1-2 per cent annually when markets are steady. But Mr Spitznagel says his formative years on the Chicago trading floor was a good training for such a strategy. “I learnt to lose money in the pit. The way I traded, I had to be willing to look like a fool for a long time, taking tiny losses and waiting for a big win,” he says. One of Universa’s claims to fame is its relationship with Nassim Taleb, the author of Fooled by Randomness and The Black Swan. Mr Taleb, a professor at New York University Polytechnic Institute and a celebrity in the world of derivatives, is listed as a “Distinguished Scientific Advisor” on its website and has a stake in Universa. This is Mr Taleb and Mr Spitznagel’s second endeavour together: Mr Spitznagel worked for Mr Taleb at his hedge fund Empirica Capital, which was started in 1999. After some solid gains the fund closed in 2004 after years of subpar returns. “Mark and I have been studying extreme events and protecting portfolios from them together since the 90s,” Mr Taleb told the FT. “People are finally discovering that being protected from fragility in the financial system is a necessity rather than an option.” His latest venture has enjoyed more success. Universa started in January 2007 after its success during the financial crisis, when it reportedly gained about 100 per cent. The firm now protects about $6bn of investor money, backed by about $200m-$300m of capital (the firm declined to say exactly how much because of regulatory issues). Fees are paid on the nominal amount insured against calamity, rather than the capital invested. Still, sometimes it can go wrong. After the financial crisis, Universa bet that the Fed pumping money into the system would spur hyperinflation. So far inflation has been notable for its absence, but Mr Spitznagel is undeterred. “This is the greatest monetary experiment in history. Why wouldn’t it lead to the biggest collapse? My strategy doesn’t require that I’m right about the likelihood of that scenario. Logic dictates to me that it’s inevitable,” he says. While some money managers are critical of a strategy that “sells fear,” there are others who share Mr Spitznagel’s views that another reckoning is imminent. Among those who share his worldview is former US presidential candidate, Senator Rand Paul, and his father Ron Paul. The elder Paul wrote the introduction to Mr Spitznagel’s 2013 book, The Dao of Capital. “As one of the leading voices in the country on economic policy, Mark has been a key friend and ally, and I’m thankful for his always-ready advice,” Senator Paul told the FT. But most investors will be praying he is wrong. by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

The Telegraph May 11, 2016 Italy is running out of economic time. Seven years into an ageing global expansion, the country is still stuck in debt-deflation and still grappling with a banking crisis that it cannot combat within the paralyzing constraints of monetary union. "We have lost nine percentage points of GDP since the peak of the crisis, and a quarter of our industrial production," says Ignazio Visco, the rueful governor of the Banca d'Italia. Each year Rome hopefully pencils in a fall in the ratio of public debt to GDP, and each year the ratio rises. The reason is always the same. Deflationary conditions prevent nominal GDP rising fast enough to outgrow the debt. The putative savings from drastic fiscal austerity - cuts in public investment - were overwhelmed by the crushing arithmetic of the 'denominator effect'. Debt was 121pc in 2011, 123pc in 2012, 129pc in 2013. It came close to levelling out last year at 132.7pc, helped by the tailwinds of a cheap euro, cheap oil, and Mario Draghi's fairy dust of quantitative easing. This triple stimulus is already fading before the country escapes the stagnation trap. The International Monetary Fund expects growth of just 1pc this year. The global window is closing in any case. US wage growth will probably force the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates and wild speculation will certainly force China to rein in its latest credit boom. Italy will enter the next downturn - perhaps early next year - with every macro-economic indicator in worse shape than in 2008, and half the country already near political revolt. "Italy is enormously vulnerable. It has gone through a whole global recovery with no growth," said Simon Tilford from the Centre for European Reform. "Core inflation is at dangerously low levels. The government has almost no policy ammunition to fight recession." Italy needs root-and-branch reform but that is by nature contractionary in the short-run. It is viable only with a blast of investment to cushion the shock, says Mr Tilford, but no such New Deal is on the horizon. Legally, the EU Fiscal Compact obliges Italy to do the exact opposite: to run budget surpluses large enough to cut its debt ratio by 3.6pc of GDP every year for twenty years. Do you laugh or cry? "There is a very real risk that Matteo Renzi will come to the conclusion that his only way to hold on to power is to go into the next election on an openly anti-euro platform. People are being very complacent about the political risks," said Mr Tilford. Indeed. The latest Ipsos MORI survey shows that 48pc of Italians would vote to leave the EU as well as the euro if given a chance. The rebel Five Star movement of comedian Beppe Grillo has not faded away, and Mr Grillo is still calling for debt default and a restoration of the Italian lira to break out of the German mercantilist grip (as he sees it). His party leads the national polls at 28pc, and looks poised to take Rome in municipal elections next month. The rising star on the Italian Right, the Northern League's Matteo Salvini, told me at a forum in Pescara that the euro was "a crime against humanity" - no less - which gives you some idea of where this political debate is going. The official unemployment rate is 11.4pc. That is deceptively low. The European Commission says a further 12pc have dropped out of the data, three times the average EU for discouraged workers. The youth jobless rate is 65pc in Calabria, 56pc in Sicily, and 53pc in Campania, despite an exodus of 100,000 a year from the Mezzogiorno - often in the direction of London. The research institute SVIMEZ says the birth rate in these former Bourbon territories is the lowest since 1862, when the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in Naples began collecting data. Pauperisation is roughly comparable to that in Greece. Industrial output has dropped by 35pc since 2008, and investment by 59pc. SVIMEZ warns that the downward spiral is turning a cyclical crisis into a "permanent state of underdevelopment". In short, southern Italy is close to social collapse, and there is precious little that premier Renzi can do about it without reclaiming Italian economic sovereignty. The story of Italy's disastrous ordeal with the euro is long and complex. The country had a large trade surplus with Germany in the mid-1990s, before the exchange rates were fixed in perpetuity. Those were the days when it could still devalue its way back to viability, much to the irritation of the German chambers of commerce. Suffice to say that Italy lost 30pc in unit labour cost competitiveness against Germany over the next fifteen years, in part because Germany was screwing down wages to steal a march on others, but also because globalization hit the two countries in different ways. Italy tipped into a 'bad equilibrium'. Its productivity has dropped by 5.9pc since 2000, a breath-taking collapse. Blame is pointless. The anthropological critique of EMU was always that it would be unworkable to corral Europe's prickly, heterogeneous nation cultures into a tight monetary union, and so it has proved. You can fault successive Italian governments, but the relevant issue today is that Italy cannot now break out of the trap. Efforts to claw back competitiveness by means of an internal devaluation merely poison debt dynamics and perpetuate depression. The result before our eyes is industrial implosion. Into this combustible mix we can now add a banking crisis that exposes the dysfunctional character of EMU, and it is getting worse by the day. The share price of Italy's biggest bank Unicredit fell 4.5pc today. It has lost half its value over the last six months, emblem of an untouchable sector with €360bn of non-performing loans (NPLs) - 19pc of the Italian banking balance sheets. This is the highest in the G20, though some say the real figure in China is close. The banks have yet to write down €83.6bn of the worst debts (sofferenze). They have not done so for a reason. Their capital ratios are too low, hence the gnawing fears of forced recapitalization and a creditor haircut under the EU's new 'bail-in" laws. This is politically explosive. Tens of thousands of Italian depositors at small regional banks have already faced the axe, learning to their horror that they had signed away their savings unknowingly. The Banca d'Italia said the EU bail-in law has become “a source of serious liquidity risk and financial instability” and should be revised before it sets off a run on the banking system. The government wanted to follow the Anglo-Saxon model and create a publicly-funded 'bad bank' to run off the NPLs but this breached eurozone rules. "They basically tried all possible routes," said Lorenzo Codogno, former chief economist at the Italian treasury and now at the London School of Economics. The ECB's surveillance police has made matters worse. "They keep asking the banks to put more money. It is normal to have high NPLs after a long deep and recession, so the ECB should not be doing this. It is effectively increasing instability," he said. In the end the government launched its hybrid €4.25bn 'Atlante' fund, twisting the arms of Italian banks and insurers to take part. The aim is to soak up bad debts, to prevent a fire-sale of assets to foreign vulture funds at levels that would wipe out capital, and to save Unicredit from having to raise fresh money in a hostile market. Atlante is fraught with hazard. Silvia Merler from the Bruegel think-tank says it draws healthier banks into the quagmire, increasing systemic risk. Nor has it succeeded in buying time in any case. Italy is now in the worst of all worlds. It cannot take normal sovereign action to stabilize the banking system because of EU rules and meddling, yet there is no EMU banking union worth the name and no pan-EMU deposit insurance to share the burden. "We're going to be in big trouble if there is another recession," said Mr Codogno. "The whole way the banking union is operating is symptomatic of EU practice. Countries have to abide by a slew of rules and regulations but when a crisis hits there is no solidarity: none of the benefits are forthcoming," said Mr Tilford. Mr Renzi may ultimately face an ugly choice. Either he tells the EU authorities to go to Hell, or he stands by helpless as the Italian banking sytem implodes and the country spins into sovereign insolvency. Italy is not Greece. It cannot be crushed into submission. Besides, the 'poteri forti' of Italian industry whisper in your ear these days that ejection from the euro might not be so awful after all. In fact it might be the only way to avert a catastrophic deindustrialization of their country before it is too late. by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

The Telegraph May 10, 2016 The eurozone’s short-lived recovery is already losing steam as stimulus fades and deep problems resurface, raising fears of yet another false dawn and a potential deflation trap if there is any external shock over coming months. Industrial output fell in 1.3pc Germany and 0.3pc in France in March as manufacturing stalled, confounding expectations for robust expansion. The relapse in a string of countries suggests that flash estimates of 0.6pc GDP growth in the first quarter were too optimistic and may have to be cut. “The recovery is not gaining any traction. I am really quite worried about another spasm of the debt crisis over the summer,” said Lars Christensen from Markets and Money Advisory. “Markets are beginning to lose faith that the European Central Bank can deliver stimulus, and we are seeing the return of problems in public finances in Portugal, Spain, and Italy. That is becoming a key story,” he said. The eurozone has been basking in a sweet spot over the last year, with stimulus from cheap oil, a weaker euro, ECB bond purchases, and an end to fiscal austerity, all coming together in a "perfect positive storm". “If that can’t produce growth, nothing will,” said Nouriel Roubini from New York University. Each of these effects is losing its potency, or is turning into a cyclical headwind. Oil prices have jumped by 75pc since early February. The euro’s trade-weighted index has risen by 5pc over the last six months, and is now higher than it was when the ECB launched quantitative easing in a frantic effort to drive it down. Looser fiscal policy has been too scattered and weak to galvanize lasting investment, and the initial sugar rush is now ebbing. Marchel Alexandrovich from Jefferies said the ECB has so far failed to build a buffer against a deflationary shock. “What catches the eye is that services inflation has been running at just 0.2pc over the last six months. They are really not that far away from deflation.” “Things are still holding up on the surface but people may be underestimating the underlying deterioration. What they need is a big programme of infrastructure spending, monetized by quantitative easing,” he said. This could be done legally if the European Investment Bank issued bonds that were then bought by the ECB, a plan first pushed by Greece’s Yanis Varoufakis. Professor Paul de Grauwe from the London School of Economics said QE may keep the cyclical wolf from the door for another year but this is no solution in itself. “It is not enough to sustain growth,” he said. “We need an investment expansion of 2pc to 3pc of GDP to reach lift-off, and it makes sense when you can borrow so cheaply. But to talk about this is heresy. You hit a brick wall. They think it is devilish,” he said. His pleas were echoed this week by the ECB’s vice-president Vitor Constancio, who warned that central banks cannot hold up the sky alone and called for “growth-friendly fiscal policies” with reforms to keep the fragile recovery alive. He said the world economy was prey to "secular forces" that have lowered long-term growth rates, making it even harder to overcome the deflationary hangover of accumulated debt. There are plenty of trouble spots in sight. Italy is struggling to manage a banking crisis as bad debts reach 19pc of lenders’ balance sheets, while Spain and Portugal are both in political turmoil and flouting EU deficit rules – leaving it unclear whether the ECB could legally back them in a crisis under its rescue machinery (OMT). Raoul Ruparel from Open Europe said Spain’s apparent mini-boom is driven by a burst of pent-up consumer spending that cannot last: “Corporations are still heavily indebted and they are not investing. I don’t see this recovery as sustainable." The eurozone is in much better shape than it was in 2011 and 2012 before Mario Draghi had established full control over the ECB. Yet there is still no fiscal union, and calls for Eurobonds have been blocked by Germany, Holland, Finland, and Austria. Nor is there a genuine banking union to break the "doom-loop" between banks and sovereign states, each dragging the other down in a crisis. “Sovereigns are still exposed to the catastrophic risk of shouldering the cost of a banking system rescue. What matters for markets is who bears the ultimate, catastrophic risk,” said Jean Pisani-Ferry, France’s Commissioner General for Policy Planning. This is eurozone’s Achilles Heel. It is sure to be tested in the next global downturn. Stanley Druckenmiller May 4, 2016 Full Speech - The Sohn Investment Conference The Endgame When I started Duquesne in February of 1981, the risk free rate of return, 5 year treasuries, was 15%. Real rates were close to 5%. We were setting up for one of the greatest bull markets in financial history as assets were priced incredibly cheaply to compete with risk free rates and Volcker’s brutal monetary squeeze forced much needed restructuring at the macro and micro level. It is not a coincidence that strange bedfellows Tip O’Neill and Ronald Reagan produced the last major reforms in social security and taxes shortly thereafter. Moreover, the 15% hurdle rate forced corporations to invest their capital wisely and engage in their own structural reform. If this led to one of the greatest investment environments ever, how can the mirror of it, which is where we are today, also be a great investment environment? Not a week goes by without someone extolling the virtues of the equity market because “there is no alternative” with rates at zero. The view has become so widely held it has its own acronym, “TINA”. Not only valuations were low back in 1981 but financial leverage was less than half of what it is today. The capacity of credit inspired growth was still ahead of us. The policy response to the global crisis was, and more importantly, remains so forceful that it has prevented any real deleveraging from happening. Leverage has actually increased globally. Ironically from where I stand, that has been the intended goal of most policymakers today. Let me focus on two of the main policies that have not only prevented a clean-up of past excesses in developed markets but also led to an explosion in leverage in Emerging markets. The first of these policies has been spearheaded by the Federal Reserve Bank in the US. By most objective measures, we are deep into the longest period ever of excessively easy monetary policies. During the great recession, rates were set at zero and they expanded their balance sheet by $1.4T. More to the point, after the great recession ended, the Fed continued to expand their balance sheet another $2.2T. Today, with unemployment below 5% and inflation close to 2%, the Fed’s radical dovishness continues. If the Fed was using an average of Volcker and Greenspan’s response to data as implied by standard Taylor rules, Fed Funds would be close to 3% today. In other words, and quite ironically, this is the least “data dependent” Fed we have had in history. Simply put, this is the biggest and longest dovish deviation from historical norms I have seen in my career. The Fed has borrowed more from future consumption than ever before. And despite the US global outperformance, we currently have the most negative real rates in the G-7. At the 2005 Ira Sohn Conference, looking at a more muted but similar deviation, I argued that the Greenspan Fed was sowing the seeds of an historical housing bubble fed by reckless sub-prime borrowing that would end very badly. Those policy excesses pale in comparison to the duration and extent of today’s monetary experiment. The obsession with short-term stimuli contrasts with the structural reform mindset back in the early 80s. Volcker was willing to sacrifice near term pain to rid the economy of inflation and drive reform. The turbulence he engineered led to a productivity boom, a surge in real growth, and a 25 year bull market. The myopia of today’s central bankers is leading to the opposite, reckless behavior at the government and corporate level. Five years ago, one could have argued it was in search of “escape velocity.” But the sub-par economic growth we are experiencing in the 8th year of a radical monetary experiment and in Japan after more than 20 years has blown that theory out of the water. And smoothing growth over a cycle should not be confused with consistently attempting to borrow consumption from the future. The Fed has no end game. The Fed’s objective seems to be getting by another 6 months without a 20% decline in the S&P and avoiding a recession over the near term. In doing so, they are enabling the opposite of needed reform and increasing, not lowering, the odds of the economic tail risk they are trying to avoid. At the government level, the impeding of market signals has allowed politicians to continue to ignore badly needed entitlement and tax reform. Look at the slide behind me. The doves keep asking where is the evidence of mal-investment? As you can see, the growth in operating cash flow peaked 5 years ago and turned negative year over year recently even as net debt continues to grow at an incredibly high pace. Never in the post-World War II period has this happened. Until the cycle preceding the great recession, the peaks had been pretty much coincident. Even during that cycle, they only diverged for 2 years, and by the time EBITDA turned negative year over year, as it has today, growth in net debt had been declining for over 2 years. Again, the current 5-year divergence is unprecedented in financial history! And if this wasn’t disturbing enough, take a look at the use of that debt in this cycle. While the debt in the 1990’s financed the construction of the internet, most of the debt today has been used for financial engineering, not productive investments. This is very clear in this slide. The purple in the graph represents buybacks and M/A vs. the green which represents capital expenditure. Notice how the green dominates in the 1990’s and is totally dominated by the purple in the current cycle. Think about this. Last year, buybacks and M&A were $2T. All R&D and office equipment spending was $1.8T. And the reckless behavior has grown in a non-linear fashion after 8 years of free money. In 2012, buybacks and M&A were $1.25T while all R&D and office equipment spending was $1.55T. As valuations rose since then, R&D and office equipment grew by only $250b, but financial engineering grew $750b, or 3x this! You can only live on your seed corn so long. Despite no increase in their interest costs while growing their net borrowing by $1.7T, the profit share of the corporate sector peaked in 2012. The corporate sector today is stuck in a vicious cycle of earnings management, questionable allocation of capital, low productivity, declining margins, and growing indebtedness. And we are paying 18X for the asset class. A second source of myopic policies is now coming from China. In response to the global financial crisis, China embarked on a $4 trillion stimulus program. However, because they had engaged in massive infrastructure investment the previous 10 years, and that was the primary stimulus pipe they chose; this only aggravated the overcapacity in the investment side of their economy. Not surprisingly, this only provided a short term pop in nominal growth. While we were worried about bank assets to GDP in 2012, incredibly, credit has increased by 70% of GDP in the 4 years since then. Just to put this in perspective, this means that since 2012 the Chinese banking sector has allowed credit to grow by the amount of the entire Brazilian GDP per year! Picture the entire Brazilian production in new houses and infrastructure. Incredibly, all this credit growth has been accompanied by a fall in nominal GDP growth from 15% to 5%. This is an extremely toxic cocktail for companies that have borrowed at 10% expecting 15% sales growth. Our strong suspicion therefore is that a large part of this growth is just credit flowing to otherwise insolvent borrowers. How else to explain the lack of NPL problem in heavy industries hit by lower prices and sales growth? As a result, unlike the pre-stimulus period, when it took $1.50 to generate a $1.00 of GDP, it now takes $7. This is extremely rare and dangerous. The most recent historical analogue was the U.S. in the mid- 2000’s when the debt needed to generate a $ of GDP increased from $1.50 to $6 during the subprime mania. Two years ago, we had hope the Chinese were ready to accept a slowdown in exchange for reform. Unfortunately, with the encouragement of the G-7, they have opted for another investment focused fiscal stimulus which may buy them some time but will exacerbate their problem. They do not need more debt and more houses. As the chart shows, this will remove a major cylinder from the engine of world growth. I have argued that myopic policy makers have no end game, they stumble from one short term fiscal or monetary stimulus to the next, despite overwhelming evidence that they only produce an ephemeral sugar high and grow unproductive debt that impedes long term growth. Moreover, the continued decline of global growth despite unprecedented stimulus the past decade suggests we have borrowed so much from our future for so long the chickens are coming home to roost. Three years ago on this stage I criticized the rationale of fed policy but drew a bullish intermediate conclusion as the weight of the evidence suggested the tidal wave of central bank money worldwide would still propel financial assets higher. I now feel the weight of the evidence has shifted the other way; higher valuations, three more years of unproductive corporate behavior, limits to further easing and excessive borrowing from the future suggest that the bull market is exhausting itself. If we have borrowed more from our future than any time in history and markets value the future, we should be selling at a discount, not a premium to historic valuations. It is hard to avoid the comparison with 1982 when the market sold for 7x depressed earnings with dozens of rate cuts and productivity rising going forward vs. 18x inflated earnings, productivity declining and no further ammo on interest rates.

The lack of progress and volatility in global equity markets the past year, which often precedes a major trend change, suggests that their risk/reward is negative without substantially lower prices and/or structural reform. Don’t hold your breath for the latter. While policymakers have no end game, markets do. On a final note, what was the one asset you did not want to own when I started Duquesne in 1981? Hint…it has traded for 5000 years and for the first time has a positive carry in many parts of the globe as bankers are now experimenting with the absurd notion of negative interest rates. Some regard it as a metal, we regard it as a currency and it remains our largest currency allocation. Sohn Investment Conference

May 4, 2016 Stanley Druckenmiller was Managing Director at Soros Fund Management, where he served as Lead Portfolio Manager of the Quantum Fund and Chief Investment Officer of Soros and had overall responsibility for funds with a peak asset value of $22 billion. Stanley Druckenmiller went on to found Duquesne Capital Management, which he ran until 2010 when the firm closed its doors to outside money. Today, Druckenmiller continues to manage money under the name Duquesne Family Office, but he tends to avoid giving stock-specific ideas at conferences. Instead, Druckenmiller tends to weigh in on broader economic topics with the odd political opinion thrown in. “I have argued that the myopic policy makers have no endgame,” billionaire Stanley Druckenmiller said towards the end of a scathing twenty minute romp through all of the world’s economic problems. The U.S. debt is out of control, China is even worse, but the biggest offender of all is the Federal Reserve, Druckenmiller said. Corporations in the United States are stuck in the mud, forlorn of growth, unwilling to invest, and addicted to share buybacks to gin up their stocks. It is a sentiment Druckenmiller has had for years, but the famed hedge fund manager indicated he really means it now. Eleven years ago, Druckenmiller warned the Sohn audience of then-Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan’s blunders in inflating an epic mortgage bubble, which was sure to crash. On Wednesday, he said the bubble inflated by former chair Ben Bernanke and current chairwoman Janet Yellen is many magnitudes worse. The Fed, Druckenmiller said, is using low interest rates to ease borrowing costs and smooth over growing problems in the global economy. And this radical Central Bank accommodation is leading to unproductive investment, and is an issue that is even worse in China, an engine of global demand. Whether it is S&P 500 Index corporations, U.S. households or the state-managed economy in China, Druckenmiller believes cheap money is borrowing from future growth, and will backfire spectacularly. ”While policy makers have no endgame, markets do,” he said. by John Mauldon

Mauldin Economics Outside the Box May 5, 2016 I have long been a critic of government inflation statistics. Not so much with regard to the methodology they use, but because the measure of “average” inflation across the broad economy doesn’t really describe the inflation that the majority of Americans experience. I’ve written about that at length in several letters. Now my good friend Ron Arnott, along with his associate Lillian Wu, presents us with a research paper that lays out what inflation actually looks like for most Americans – and the picture is not pretty. The authors demonstrate that inflation in the main four categories – rent, food, energy, and medical care – has been running at roughly 3% since 1995, significantly more than the 2.2% the BLS data yields – especially when you think about the compounding effect. In the 20 years since ’95, that 0.8% differential has compounded to over 20%, which has to be deflated against incomes. When you look at the stagnant income growth of the middle class and then reduce that income by 20%, rather than by the official inflation rate, it is not hard to grasp why significant majorities in both political parties are pissed off (to employ a technical economics term). Quoting from Rob and Lillian’s paper: Since 1995, households have expected inflation to be, on average, 3.0%, whereas realized inflation has been around 2.2%, leaving an inflation “gap” of almost 0.8%. What explains this gap? The following is our hypothesis. The four “biggies” for the average American are rent, food, energy, and medical care, in approximately that order. These “four horsemen” have been galloping along at a faster rate than headline CPI. According to the BLS definition, they compose about 60% of the aggregate population’s consumption basket, but for struggling middle-class Americans, it’s closer to 80%. For the working poor, spending on these four categories can stretch to as much as 90% of total spending. Families have definitely been feeling the inflation gap, that difference between headline CPI and inflation in the prices of goods they most frequently consume. This paper is one of the most powerful indictments of central bank policy that I have read in a long time (even if the authors didn’t intend it to be that). It reinforces my contention that the models central banks create and the data they base those models on are inherently flawed. And those flaws are compounded because the banks’ manipulation of interest rates (the price of money) is perversely doing the opposite of what they think it should do. This is going to cause more mischief and economic pain during the next recession than any of us are prepared for or can even imagine. Seriously, we’re going to have to restructure our expectations and strategies for our portfolios to deal with what I think is developing into a policy error of biblical proportions. by John Mauldin

April 13, 2016 You often hear me harping on the dangers of too much debt, and I keep my eyes peeled for significant work that backs up my concerns. In today’s Outside the Box good friend Dr. Lacy Hunt of Hoisington Investment Management gives us more ammunition to take on those who just don’t seem to get that the endless piling up of debt is not a sustainable way to run an economy. The most striking feature of the US economy’s performance in 2015, according to Lacy, was a massive advance in nonfinancial debt that kept the economy stuck in the doldrums of subpar growth. US nonfinancial debt rose 3.5 times faster than GDP last year. (Nonfinancial debt is the sum of household debt, business debt, federal debt, and state and local government debt.) Lacy points out unfavorable trends in each component of nonfinancial debt: Household debt: Delinquencies in household debt moved higher even as financial institutions continued to offer aggressive terms to consumers, implying falling credit standards. Furthermore, the New York Fed said subprime auto loans reached the greatest percentage of total auto loans in ten years. Moreover, they indicated that the delinquency rate rose significantly. Business debt: Last year business debt, excluding off balance sheet liabilities, rose $793 billion, while total gross private domestic investment (which includes fixed and inventory investment) rose only $93 billion. Thus, by inference this debt increase went into share buybacks, dividend increases and other financial endeavors…. When business debt is allocated to financial operations, it does not generate an income stream to meet interest and repayment requirements. Such a usage of debt does not support economic growth, employment, higher paying jobs or productivity growth. Thus, the economy is likely to be weakened by the increase of business debt over the past five years. Federal debt: U.S. government gross debt, excluding off balance sheet items, gained $780.7 billion in 2015 or about $230 billion more than the rise in GDP…. The divergence between the budget deficit and debt in 2015 is a portent of things to come. This subject is directly addressed in the 2012 book The Clash of Generations, published by MIT Press, authored by Laurence Kotlikoff and Scott Burns. They calculate that on a net present value basis the U.S. government faces liabilities for Social Security and other entitlement programs that exceed the funds in the various trust funds by $60 trillion. This sum is more than three times greater than the current level of GDP. State and local government debt: State and local governments … face adverse demographics that will drain underfunded pension plans…. The state and local governments do not have the borrowing capacity of the federal government. Hence, pension obligations will need to be covered at least partially by increased taxes, cuts in pension benefits or reductions in other expenditures. Lacy adds this note on total debt, which includes nonfinancial, financial, and foreign debt: Total debt … increased by $1.968 trillion last year. This is $1.4 trillion more than the gain in nominal GDP. The ratio of total debt-to-GDP closed the year at 370%, well above the 250-300% level at which academic studies suggest debt begins to slow economic activity. Lacy makes the key point that overindebtedness impairs monetary policy, not just in the US but globally: The Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and the People’s Bank of China have been unable to gain traction with their monetary policies…. Excluding off balance sheet liabilities, at year-end the ratio of total public and private debt relative to GDP stood at 350%, 370%, 457% and 615%, for China, the United States, the Eurocurrency zone, and Japan, respectively…. The debt ratios of all four countries exceed the level of debt that harms economic growth. As an indication of this over-indebtedness, composite nominal GDP growth for these four countries remains subdued. The slowdown occurred in spite of numerous unprecedented monetary policy actions – quantitative easing, negative or near zero overnight rates, forward guidance and other untested techniques. Read it and think about this, gentle reader. We’re digging a great big hole that is likely to cave in on us before we manage to claw our way back out of it. We need to “wargame” how we respond in our personal lives. That is going to be a big focus of my letters in the coming months. Weekly Market Comment

by John P. Hussman, Ph.D March 21, 2016 Extinction Burst In behavioral psychology, a “reinforcer” is anything that increases the likelihood of a given behavior. Reducing an undesirable behavior usually involves two steps: a) “extinction,” where the reinforcement for the existing behavior is removed, and; b) “substitution,” where another behavior is introduced that hopefully satisfies the underlying need in a more desirable and effective way. Now, when a given behavior stops being reinforced, one might expect the behavior to be abandoned. Instead, and particularly when no substitute behavior is available, you’ll actually see an initial “extinction burst” - a nearly frantic increase in the frequency and the intensity of the behavior. Consider central bankers. For the past several years, global central banks have pursued increasingly deranged monetary policies, creating massive distortions in financial markets. It’s easy to point to these effects on the financial markets, as Bernanke, Kuroda, Draghi and other central bankers have emphasized, as evidence that central bank policy is “working.” Unfortunately, that’s not how one measures the impact of monetary policy on the real economy. The correct approach is to compare how the economy has actually done versus how it would have been expected to do with and without those interventions. Specifically, you estimate the trajectory of output, employment, and other variables using past values of a) only non-monetary variables like output and employment, and b) both non-monetary variables and monetary ones (typically using a statistical method known as "vector autoregression" or VAR). What we, and others, have found, is that all of this deranged monetary policy has raised the level of GDP, industrial production, and employment by barely 1% from what would have been expected in the absence of these interventions. On January 29, a week after insisting that a move to negative rates was not under consideration, Bank of Japan Governor Harohiko Kuroda announced a rate cut to -0.1%. On February 18 he reiterated that the BOJ was prepared to ease further. He wavered on that stance at the end of February, but shifted again last week, saying that a move to even deeper negative rates was possible. Meanwhile, facing economic erosion in Europe, Mario Draghi came out on February 15 saying “we will not hesitate to act.” He followed on March 10 with his “bazooka” including a rate cut to -0.4%, an increase in the pace of QE, and a broadening of ECB purchases to include investment-grade, non-bank corporate bonds. On Wednesday, Janet Yellen announced that the expected pace of Fed rate hikes this year was likely to be slower than expected, as a result of weak global economic conditions and widening credit spreads. Aside from a one or two-day knee-jerk response, these moves have had very little sustained impact on the equity markets. Japan’s Nikkei index is down about 5% since the day after Kuroda’s rate-cut announcement. The Dow Jones EuroStoxx Index is also down since the day after Draghi’s bazooka. One suspects that the response of the S&P 500 to Yellen’s dovishness will be similarly short-lived, though we need not rely on that. Given the continued sequence of erosion in economic measures, central bankers continue to point to the financial markets as evidence that their policies are “working.” Now even those effects have become unreliable. The press conferences following central bank moves increasingly sound like real people have been replaced with “bots,” mechanically retrieving phrases to make a historically extreme monetary stance sound prudent and to simultaneously encourage speculation. Every phrase has to be weighed individually, so one observes a halting, almost rambling quality to the remarks. Consider this response by Janet Yellen to the first question in the press conference following the Fed’s dovish monetary policy statement on Wednesday: “So, you have seen a shift, uh, this time, in most participants assessments of the appropriate path for policy, and as I tried to indicate, I think that largely reflects a somewhat slower projected path for global growth, for growth in the global economy outside the United States, um, and for some tightening in credit conditions in the form of an increase in spreads, and, um, those changes in financial conditions and in, uh, the path of the global economy have, uh, induced, uh changes in the assessment of individual participants in what path is appropriate to achieve our objectives, so that’s what you, uh, see, that’s what you see. Now I guess you asked me also, what would we need to see, um, to continue raising rates, and I think it’s worth pointing out here that, um, the committee, most participants do continue to um, envision that if economic developments unfold as they expect, that further increases in the federal funds rate will prove appropriate over time, um, most participants anticipate that uh, and, uh, that the pace will be gradual.” - Janet Yellen, March 16, 2016 press conference following FOMC meeting This sudden escalation of dovish pronouncements by central bankers isn’t sound monetary policy, being conducted based on demonstrated cause-and-effect relationships between policy tools and the real economy. No, this is an extinction burst. Central bankers are behaving like lab rats frantically pressing a bar in hope that more food pellets will come out of the chute. They ain’t comin’. --- The problem with punishing saving in order to encourage more consumption is that it’s ineffective, and also leaves the economy with nothing to show for it. The wealth of a nation consists of its stock of real private investment (e.g. housing, capital goods, factories), real public investment (e.g. infrastructure), intangible intellectual capital (e.g. education, inventions, organizational knowledge and systems), and its endowment of basic resources such as land, energy, water, and the environment. In an open economy, one would include the net claims on foreigners. Everything else cancels out, because every security is an asset of the holder, but a liability of the issuer. If we want greater prosperity, it will come from expanding our productive capacity and defending our natural resources. Monetary authorities have now become little more than lab rats on a frantic extinction burst. If there are no adults in the room among our policy-makers who are willing to pursue the appropriate substitute behavior - expanding productive investment through fiscal means - we’re going to have a deeper and more concerted global economic downturn than is already likely. I remain convinced that monetary authorities have already ensured a financial collapse in the coming years that is baked-in-the-cake as a result of obscene valuations. That outcome will unfold nearly regardless of economic prospects. By encouraging acute financial distortions, enabling massive issuance of speculative-grade securities and stock buybacks at near-record valuations, and repeatedly diverting national savings toward speculative malinvestment, the concerted behavior of central banks is increasingly pushing the global economy toward financial crisis and depressed long-term growth. There is no hope for long-term economic prosperity if we place our faith in the monetary policies of deranged bankers and ivory tower college professors. All they can do is to buy interest-earning bonds and replace them with zero-interest paper. How ignorant must we be to believe that financial bubbles will carry us to prosperity without consequences, and how many collapses must we endure before we focus on strengthening our own legs? The irony of economics is that when we pursue policies that encourage speculative malinvestment and make productive investment scarce, the pie gets smaller but a larger share of it goes to the owners of existing capital. The “rents” are always highest for those resources that are most scarce. If we really want more jobs, higher labor productivity, stronger growth, better real wages, a balanced income distribution, and a return to long-term economic prosperity, only an expansion of real productive investment - at every level of the economy - will do the job. Ever more deranged monetary policy will not.

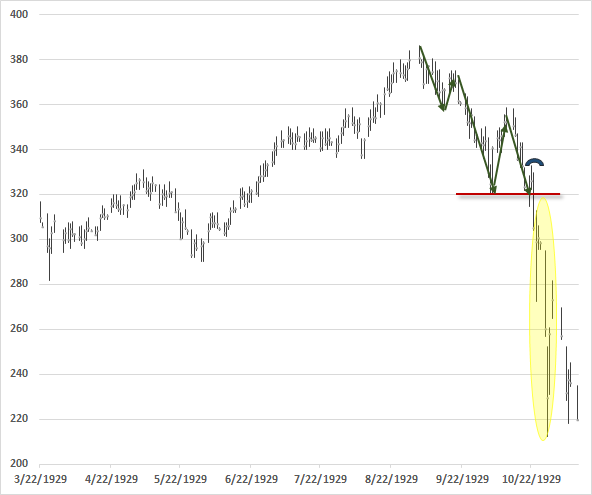

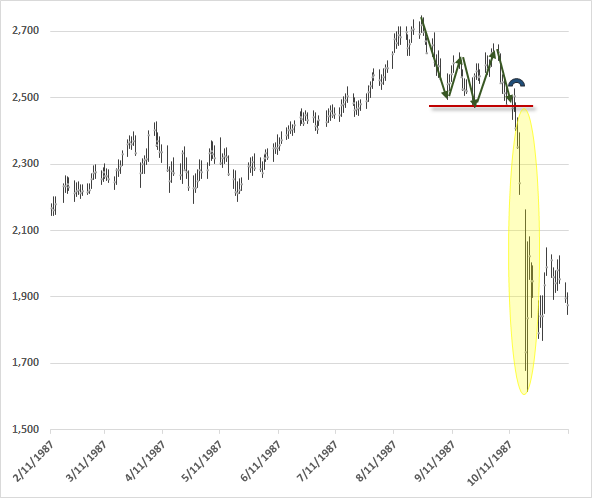

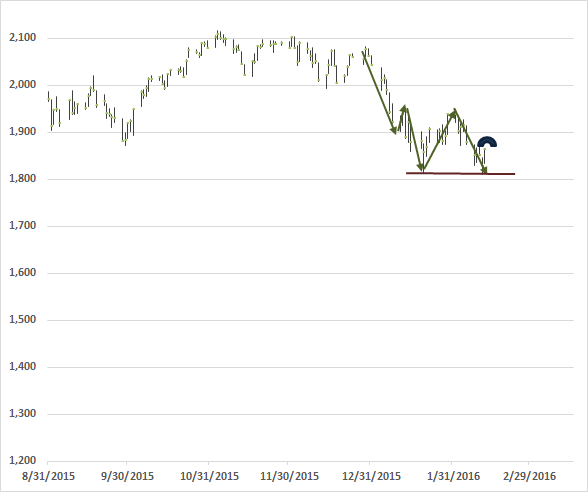

The economy is unlikely to reach "escape velocity" due to the influence of Federal Reserve and other central banks' policies, billionaire investor Stanley Druckenmiller said Wednesday.

"We have pulled so much demand forward and borrowed so much from our future, so much financial engineering has gone on," the former Duquesne Capital Management chairman and president told CNBC's "Squawk Box." Druckenmiller said he can't see the U.S. economy breaking free of sluggish growth any time soon. "This idea that we're going to have escape velocity in the economy, I just don't see it," he said. "At best we're going to muddle through," he said. The U.S. economy grew by 1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2015, according to the second of three readings released last week by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Druckenmiller said the market was overvalued heading into last year, following "huge" liquidity support for a number of years. But that support is now dissipating as China and Saudi Arabia scale back purchases of Western assets, he said. "The Fed stopped injecting, so I think it's just the natural outgrowth — the markets themselves — the natural outgrowth of this cessation of liquidity," he said. The Fed held interest rates near near zero from December 2008 until a meeting of its policymaking committee in December, when they raised interest rates by 25 basis points. With bonds yielding little return, investors have flocked to stocks, raising concerns about misallocation of capital and bubbles. by John Hussman February 15, 2016 Weekly Market Comment Excerpts Given our focus on historically-informed, value-conscious, full-cycle investing, I generally don’t place much attention on short-term technical factors or specific patterns of price action. However, the current setup is one of the few exceptions. In a market return/risk classification that is already the most negative we identify, where a sustained period of speculation has given way increasing risk-aversion, the position of the market relative to very widely identified “support” (about the 1820 level on the S&P 500) is of particular note. Often, well-recognized support levels become places where dip-buyers and swing-traders line up on the buy side, on the assumption that they’ll be rewarded if the market bounces from that support, and that they can quickly cut their losses immediately if the support level is broken. The problem here is that when too many speculators set their stop-loss points at the same level, and valuations are still elevated, there may be neither speculators nor value-conscious investors willing to bid for stock anywhere near those support levels once they break. The resulting gap between eager sellers at a high level and willing buyers at a much lower level is the essential element of market crashes, because every seller requires a buyer. I’ve often observed that market crashes have historically emerged only after a familiar profile of market behavior that features a compressed market retreat of about 14% over 10-12 weeks, a rebound between 1/3 and 2/3 of that decline, a fresh retreat that slightly breaks that initial level of support, a one-day barn-burner advance, and then a collapse as the prior support level is broken. In the 1990’s, I called this pattern the lead-up to “five days of Armageddon” because historically, once rich valuations have been joined with poor market internals (what I used to call “trend uniformity”), the break of a widely-identified support level has often been followed by vertical market losses. The present widely-followed “support” shelf for the S&P 500 is roughly 14% below the 2015 market peak, but most domestic and international indices have already broken corresponding support levels. Given the obscene valuations at the 2015 peak, my impression is that a run-of-the-mill completion of the current market cycle (neither an unusual nor worst-case scenario from a historical perspective) would comprise an additional market decline of roughly 40-50% from present levels. I certainly don’t expect that kind of market loss in one fell swoop. Rather, my immediate concern is that the first leg of this decline could be quite steep. Emphatically, my concern is not simply that the market has retreated by some amount to a widely-identified support level. The issue is the context of rich valuations and poor market internals in which that market weakness has emerged, because when a widely- identified support level gives way at rich valuations, in an environment where poor market internals convey a shift toward risk-aversion among investors, the break can behave as a common trigger for concerted attempts to exit. Though the 1929 and 1987 crashes are the most salient instances, there are numerous less memorable examples across history. As I observed in my June 6, 2002 comment: “I have chosen to call this particular climate a Warning with a capital ‘W’ because every historical market crash of note is found within this one set of conditions. Those conditions are: extremely unfavorable valuations and poor trend uniformity. At present, the market is displaying the same set of characteristics as it did just prior to past market crashes. In both 1929 and 1987, the market crash began about 55 trading sessions after the peak. During those sessions, the market traced out a characteristic pattern of declining peaks and troughs, with a one-day rally just after the third trough (roughly 14% down from the peak), and then ‘five days of Armageddon.’ This is exactly the pattern that the S&P has traced since its late-March peak.” The market followed with a 24% plunge over the following 6 weeks (and an even greater loss on an intra-day basis). It took more than 5 days, but then, the S&P 500 was already down substantially from its 2000 extreme even before that plunge. Prior to the mid-1990’s, the most common “reference” index of investors was the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Presently, the most broadly followed index is the S&P 500 Index. The following charts show the general pattern I’ve described, along with the 1929 and 1987 instances. Now, perhaps the rally since Friday is instead a “successful retest” of prior support. Given that leading economic data, coupled with poor market internals, continue to indicate an imminent U.S. recession, I tend to doubt that possibility, but we’ll take the evidence as it arrives. Despite elevated valuations and deteriorating economic conditions in the U.S. and elsewhere, our immediate downside concerns would ease considerably in the event market internals were to clearly improve on our measures. Here and now, investors should ensure that their market exposures and investment horizons would allow them to tolerate a potential 40-50% market loss over the completion of this market cycle without abandoning their discipline.

Meanwhile, remember that investors, in aggregate, cannot exit the stock market, or any other market for that matter. Every security that is issued, including base money created by the Federal Reserve, must be held by some investor, at every point in time, in precisely the form it was issued, until that security is retired. The only question is how eager buyers are, relative to sellers. Prices don’t advance because money goes “into” stocks. Every dollar that a stock buyer brings into the market goes right back out in the hands of a seller. No, prices advance because buyers are more eager than sellers. Prices decline because sellers are more eager than buyers. My concern is that support for an increasingly risk-averse market now rests on the fragile resolve of dip-buying speculators primed to cut-and-run at exactly the same nearby support level, beyond which stands a rather shallow pool of powder-dry, value-conscious potential buyers who remain unwilling to commit that powder anywhere near current levels, in a risk-averse market where further central bank intervention is likely to be futile. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed