|

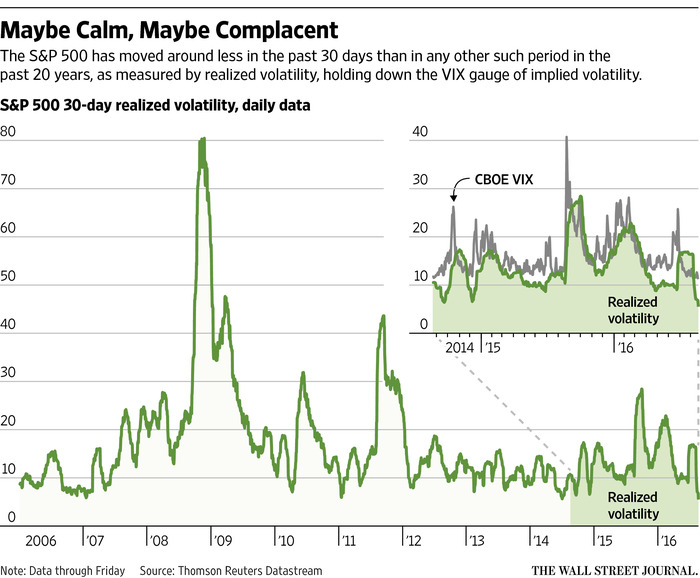

by James Mackintosh August 23, 2016 Calm has descended on the U.S. stock market. The past 30 days have been the least volatile of any 30-day period in more than two decades. Only five days during the most recent stretch saw the S&P 500 move by more than 0.5% in either direction, the lowest since the fall of 1995. Back then, the Federal Reserve was paused between rate cuts. This time around, a combination of the summer lull in trading and super-easy global monetary policy has helped drive volatility to levels seen only a dozen times in the past half-century. “Last week and the week before, you had to make sure your machine was actually on because it was flashing so infrequently,” said Jared Woodard, a strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, referring to the changes in stock prices on computer terminals. The quiet market, measured by the realized volatility—a measure of how much share prices move around—of the S&P 500, has led some to worry that a market storm may be brewing, as peaceful periods in the past have frequently ended in sharp corrections. Implied volatility, a measure of stocks’ expected future volatility and of the cost of options, has collapsed alongside realized volatility. The CBOE VIX index on Friday dropped to levels last seen in the summer of 2014—a period of calm that ended decisively with panic buying of bonds that October. The VIX, seen as Wall Street’s fear gauge, rose slightly on Monday, as the S&P fell fractionally to 2182.64. Previous periods of very low volatility were in early 2011, before the U.S.’s near-default and loss of triple-A status, and January 2007, a few months before the collapse of two Bear Stearns Cos. hedge funds marked the beginning of the credit crunch. There is more going on now than just the summer holidays. The markets are very rarely this serene, with S&P 500 realized volatility lower only a dozen times in the past half-century. In data back to 1928, this level of volatility appeared frequently only during the period from the 1951 removal of the Federal Reserve’s cap on bond yields to President Richard Nixon’s 1971 scrapping of the dollar’s link to gold. Mr. Woodard said Britain’s vote in June to leave the European Union had shocked investors, many of whom then closed their big market positions. Without many aggressive bets, there has been less need to trade on the news—and there hasn’t been much news, anyway. Investors have become more relaxed as this year’s rebound has continued, but surveys and market technical measures don’t suggest they are gripped by complacency.

Excuses can be made for the low level of the VIX, too. The implied volatility measured by the VIX should offer a premium to realized volatility, a reward for the risk taken by option sellers. Excessive complacency should show up in a shrinking risk premium, but at the moment, the gap between the VIX and realized volatility is roughly in the middle of its range from the past 20 years. The same is true for the gap between implied volatility of the next few months and further ahead. Investors seem to think volatility will pick up a bit, and again the oddity is where it stands now, not what investors are doing. “Everything feels distorted and unnatural; you know the source of that is the central banks but equally there’s nothing to stop them carrying on,” said Matt King, head of credit strategy at Citigroup. Wall Street has long seen central-bank action through the lens of the options market, since Alan Greenspan’s tenure as Fed chairman. The “Greenspan put” has under current Fed chief Janet Yellen become the “Yellen put,” named for an option used to protect against falling prices. If the Fed offers free insurance, there is no point buying your own, which ought to keep the price of puts—that is, implied volatility—down. Faith in how far central banks will protect against losses comes and goes, though. In market-speak, the Yellen put is less out of the money if a smaller price fall pushes the Fed to act. At the moment, investors seem to think the put is barely out of the money at all. The danger, then, is not so much complacency about markets, but complacency about central banks. The lesson of the past seven years is that policy makers will step in every time disaster strikes. But investors tempted to rely on the central banks should note that disasters did still strike, and markets had big falls before help arrived. The time to buy insurance is when it is cheap, and for the U.S. stock market, that is now. by Julia La Roche

Yahoo Finance August 8, 2016 Yahoo Finance: You’re the Distinguished Scientific Advisor at the hedge fund of your longtime friend Mark Spitznagel, Universa Investments, a pioneer in tail risk hedging for institutional clients. What is tail risk hedging? Nassim Nicholas Taleb: The idea at Universa is protecting clients against extreme events, those that are rare and traumatic and can threaten their survival. Counter-intuitively, by minimizing clients’ vulnerability to extreme losses through things like put options, they tend to do much better over the long run. YF: Why is it important for investors to tail risk hedge their portfolios? And how should they do this? NNT: The point is that when someone is subjected to deep losses in a large part of their portfolio, they will spend an enormous amount of their investment time rebuilding that portfolio from those losses, and any future “alpha” that is excess return from the portfolio will diverge and long term it will be much lower. Why? Because unless someone has no “uncle points,” or infinite capital, extreme loss is deterministic and does not let people emerge from it. Look at the state of under-funding of the majority of pension funds after 2008. This problem for them is only worse now. Ruin doesn’t have to be a total loss. It can be something that forces someone out of the market at the worst possible time, or, say, a 60-year old person discovering that he or she can no longer survive on future retirement income. NNT: Also, someone who minimizes their exposure to ruin by tail risk hedging can gain greater exposure to the market in other times, as they don’t have the same risk of getting stopped out as someone else so they can invest larger and for longer. Let me explain with the following example. If 100 people walk into a casino and the people who bet their money on number 27 go bust, those who bet on number 28 will not be affected. The ruin of one person does not directly affect that of others. But, if on the other hand, a person plans to walk into a casino every day for 100 days and is bust on day 27, there will be no days 28, 29, …100. So it is a mistake to look at returns of the market if you don’t have the perfect staying power, and investors should do things like tail risk hedging to ensure the highest certainty of survivorship. What Mark is doing at Universa is just that: providing staying power and robustness for clients. YF: You and Spitznagel have been doing this for a long time. What have you learned? NNT: One should stay consistent, keep an iron discipline. Mark and I have been protecting against extreme risks for nearly twenty years together. During that time, we’ve seen tail hedgers come and go by following whims and not truly focusing long term on hedging. Universa is a true “hedge” fund, as it lowers portfolio uncertainty rather than adding to it. One needs to work very, very hard at calibrating the right kind of exposure and making sure it delivers a payout in a true crash, just like Universa did in 2008, while keeping costs minimal otherwise. Refining both sides of that pendulum is the most important, and it creates its own alpha for investors. Also one can’t view hedging in isolation. The portfolio package is what matters, and investors need to know you can’t achieve one without the other. YF: What are the biggest risks out there right now? NNT: The fact that the world, as a result of quantitative easing, has seen an asset inflation that benefited the uber-rich, and that nothing has been cured. One cannot cure debt with debt, by transferring from private to public sectors. The markets will ultimately crash again, although this time it will hurt a lot more people. YF: A lot of people throw around the phrase ‘black swan’ haphazardly. What do people most commonly get wrong when talking about black swans? NNT: They don’t get that what matters is to be protected against those tail risks that matter, something easier to do than trying to predict them. The idea is to focus on portfolio robustness rather than forecasts. YF: Finally, you’re very active on social media — Twitter and Facebook. What do you think the role of social media plays in politics, the economy and the markets? NNT: Social media allowed me to go direct to the public and bypass the press, an uberization if you will, as I skip the intermediary. I do not believe that members of the press knows their own interests very well. I noticed that journalists try to be judged by other journalists and their community, not by their readers, unlike writers. This cannot be sustainable. Also, if you say it the way it is, people trust you. The central modus operandi is to avoid marketing: social media is a way to test ideas and work in progress and give-and-take to and from the readers. by Satyajit Das - author of A Banquet of Consequences, published in North America as The Age of Stagnation

Financial Times August 1, 2106 Since 2008, total public and private debt in major economies has increased by over $60tn to more than $200tn, about 300 per cent of global gross domestic product (“GDP”), an increase of more than 20 percentage points. Over the past eight years, total debt growth has slowed but remains well above the corresponding rate of economic growth. Higher public borrowing to support demand and the financial system has offset modest debt reductions by businesses and households. If the average interest rate is 2 per cent, then a 300 per cent debt-to-GDP ratio means that the economy needs to grow at a nominal rate of 6 per cent to cover interest. Financial markets are now haunted by high debt levels which constrain demand, as heavily indebted borrowers and nations are limited in their ability to increase spending. Debt service payments transfer income to investors with a lower marginal propensity to consume. Low interest rates are required to prevent defaults, lowering income of savers, forcing additional savings to meet future needs and affecting the solvency of pension funds and insurance companies. Policy normalisation is difficult because higher interest rates would create problems for over-extended borrowers and inflict losses on bond holders. Debt also decreases flexibility and resilience, making economies vulnerable to shocks. Attempts to increase growth and inflation to manage borrowing levels have had limited success. The recovery has been muted. Sluggish demand, slowing global trade and capital flows, demographics, lower productivity gains and political uncertainty are all affecting activity. Low commodity, especially energy, prices, overcapacity in many industries, lack of pricing power and currency devaluations have kept inflation low. In the absence of growth and inflation, the only real alternative is debt forgiveness or default. Savings designed to finance future needs, such as retirement, are lost. Additional claims on the state to cover the shortfall or reduced future expenditure affect economic activity. Losses to savers trigger a sharp contraction of economic activity. Significant writedowns create crises for banks and pension funds. Governments need to step in to inject capital into banks to maintain the payment and financial system’s integrity. Unable to grow, inflate, default or restructure their way out of debt, policymakers are trying to reduce borrowings by stealth. Official rates are below the true inflation rate to allow over-indebted borrowers to maintain unsustainably high levels of debt. In Europe and Japan, disinflation requires implementation of negative interest rate policy, entailing an explicit reduction in the nominal face value of debt. Debt monetisation and artificially suppressed or negative interest rates are a de facto tax on holders of money and sovereign debt. It redistributes wealth over time from savers to borrowers and to the issuer of the currency, feeding social and political discontent as the Great Depression highlights. The global economy may now be trapped in a QE-forever cycle. A weak economy forces policymakers to implement expansionary fiscal measures and QE. If the economy responds, then increased economic activity and the side-effects of QE encourage a withdrawal of the stimulus. Higher interest rates slow the economy and trigger financial crises, setting off a new round of the cycle. If the economy does not respond or external shocks occur, then there is pressure for additional stimuli, as policymakers seek to maintain control. All the while, debt levels continue to increase, making the position ever more intractable as the Japanese experience illustrates. Economist Ludwig von Mises was pessimistic on the denouement. “There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion,” he wrote. “The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as a result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.” by Bill Gross

Janus Capital August 3, 2106 When does our credit-based financial system sputter/break down? When investable assets pose too much risk for too little return. Not immediately, but at the margin, low/negative yielding credit is exchanged for figurative and sometimes literal gold or cash in a mattress. When it does, the system delevers as cash at the core, or real assets like gold at the risk exterior, become the more desirable assets. Central banks can create bank reserves, but banks are not necessarily obliged to lend it if there is too much risk for too little return. The secular fertilization of credit creation may cease to work its wonders at the zero bound, if such conditions persist. Can capitalism function efficiently at the zero bound? No. Low interest rates may raise asset prices, but they destroy savings and liability based business models in the process. Banks, insurance companies, pension funds and Mom and Pop on Main Street are stripped of their ability to pay for future debts and retirement benefits. Central banks seem oblivious to this dark side of low interest rates. If maintained for too long, the real economy itself is affected as expected income fails to materialize and investment spending stagnates. Can $180 billion of monthly quantitative easing by the ECB, BOJ, and the BOE keep on going? How might it end? Yes, it can, although the supply of high quality assets eventually shrinks and causes significant technical problems involving repo, and of course negative interest rates. Remarkably, central banks rebate almost all interest payments to their respective treasuries, creating a situation of money for nothing — issuing debt for free. Central bank "promises" of eventually selling the debt back into the private market are just that — promises/promises that can never be kept. The ultimate end for QE is a maturity extension or perpetual rolling of debt. The Fed is doing that now but the BOJ will be the petri dish example for others to follow, if/ when they extend maturities to perhaps 50 years. When will investors know if current global monetary policies will succeed? Almost all assets are a bet on growth and inflation (hopefully real growth) but in its absence at least nominal growth with some inflation. The reason nominal growth is critical is that it allows a country, company or individual to service their debts with increasing income, allocating a portion to interest expense and another portion to theoretical or practical principal repayment via a sinking fund. Without the latter, a credit-based economy ultimately devolves into Ponzi finance, and at some point implodes. Watch nominal GDP growth. In the U.S. 4-% is necessary, in Euroland 3-4%, in Japan 2-3%. What should an investor do? In this high risk/low return world, the obvious answer is to reduce risk and accept lower than historical returns. But don't you have to put your money somewhere? Yes, of course, except markets offer little in the way of double digit returns. Negative returns and principal losses in many asset categories are increasingly possible unless nominal growth rates reach acceptable levels. I don't like bonds; I don't like most stocks; I don't like private equity. Real assets such as land, gold, and tangible plant and equipment at a discount are favored asset categories. But those are hard for an individual to buy because wealth has been "financialized". How about Janus Global Unconstrained strategies? Much of my money is there. Reuters

August 2, 2106 Aug 2 Bond markets across the world are at risk to lose up to $3.8 trillion if bond yields suddenly surge back to their 2011 levels from their current historic lows, Fitch Ratings said on Tuesday. European and Japanese government bond yields have been in negative territory due to their central banks' adaptation of negative rate policies and expansion of bond purchases in 2016. Longer-dated U.S. Treasury yields reached record lows in July in a global scramble for higher-yielding sovereign debt. "As rates hit record lows, investors face growing interest rate risk. A hypothetical rapid rate rise scenario sheds light on the potential market risk faced by investors with high-quality sovereign bonds in their portfolios," Fitch Ratings said in a statement. In its analysis, a hypothetical rapid reversion of yields to 2011 levels for $37.7 trillion worth of investment-grade sovereign bonds could result in market losses of as much as $3.8 trillion, it said. From July 2011 to July 2016, the median yield on the 10-year government bonds among 34 countries fell by 2.70 percentage points. The median yield on one-year debt declined by 1.76 points, Fitch said. On July 15, there were $11.5 trillion worth of government bonds globally which offered negative yields, which were less than the $11.7 trillion on June 27. The sum of negative-yielding bonds decreased due to the yen's rally against the dollar and a rise in Japanese government yields, according to Fitch. by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

The Telegraph July 27, 2016 The great fiscal fair of 2016 has begun. The world's governments are seizing on the flimsy excuse of Brexit to prime pump their economies, hoping to stretch the ageing global cycle for a little longer. Japan's Shinzo Abe has kicked off the first round with a "shock and awe" fiscal package ostensibly worth $270bn, though the South Koreans nipped ahead of him with a $17bn raft of measures. Britain cannot be far behind as Philip Hammond prepares his first post-austerity Budget this autumn, while France's Francois Hollande and Italy's Matteo Renzi have seized on Brexit to run a coach and horses through the eurozone's fiscal rules. Brexit is manna from heaven. Brussels hardly dares to raise a squeak, knowing that revolutionaries - the Front National and Beppe Grillo's Five Star movement - are knocking at the doors of power. Fiscal austerity is over in Europe. The details of the Japanese plan will be fleshed out next week. The infrastructure measures will include a push for the Maglev magnetic levitation train, which has already attained speeds of 600 km/h on a stretch rail beneath Mount Fuji. Mr Abe's plan amounts to 5.6pc of GDP, though the actual figure will be less once double counting is stripped out. This is far bigger than sums floated earlier by officials and would pack twice the punch of Japan's stimulus after the Lehman crisis. He has already postponed plans for a rise in the consumption tax until 2019. All pretence at fiscal rectitude has been abandoned. This "precautionary" stimulus has a loose parallel with the events of 1998 following the Asian financial crisis, when the US Federal Reserve and others slashed interest rates. The global authorities overdid it - easy to say in hindsight - setting off the final explosive phase of the dotcom bubble on Wall Street, with similar excesses on Germany's Neuer Markt. This time the policy mix is subtly different. Fiscal spending is the spearhead, backed by easy money. Japan is taking advantage of the new global orthodoxy. The International Monetary Fund - once the voice of fiscal restraint - wants "growth-friendly" spending to soak up chronic slack in the world economy, mostly on infrastructure schemes with the highest multiplier effect. "There is an urgent need for G-20 countries to step up their efforts to turn growth around," it said last week. Fixed public investment in the US has fallen to a 60-year low of 2.8pc of GDP, even though Kennedy Airport is crumbling and New York's gas mains date back 120 years or more. Almost fifty of the city's bridges are rated "fracture critical" and prone to collapse. Public investment has fallen to 2.6pc in the eurozone, and has been negative in Germany for much of the last fifteen years, though the Kiel Canal is falling into the water and the country's railways still rely on 19th Century signalling in places. In Japan it has fallen from 9.7pc to 3.9pc over the last two decades. None of this makes sense when there is so much excess capital in the world and $11 trillion of sovereign debt is trading at negative yields, allowing governments to borrow for twenty or thirty years for almost nothing. Debt ratios are higher, but debt service costs in the US have dropped to just 1.2pc of GDP from 3pc in the early 1990s. Mislav Matejka and Emmanuel Cau from JP Morgan has created a series of "fiscal baskets" for investors. "We believe that it is prudent to begin adding to stocks that could benefit from a potential increase in fiscal spend and from infrastructure projects," they said. They like Haynes, Atkins, Balfour Beatty, Costain, and Kier Group, among others, in the UK; Siemens, ThyssenKrupp, Thales, Alstom, and Dong Energy in Europe; General Electric, Steel Dynamics, and Texas Instruments in the US; and Tokyo Steel, and Osaka Gas in Japan. The beauty of fiscal stimulus is that it goes directly into the veins of the real economy. There is by now near universal agreement that reliance on zero rates and quantitative easing merely to drive up asset prices have reached their limits, rewarding the owners of capital with precious little trickle-down to the working poor. The politics are poisonous. Some of Mr Abe's spending will go on child-care and homes for the elderly. You could question whether a country with public debts near 250pc of GDP can afford to borrow yet more to fund social welfare, but debt is a mirage in a world of helicopter money. The Bank of Japan is monetising the entire budget deficit, buying $76bn of bonds each month. Former Fed chief Ben Bernanke floated the idea of a “money-financed fiscal programme” earlier this month in Tokyo but some would say that is exactly what they are already doing. The BoJ's balance sheet has reached 92pc of GDP. It owns 38pc of the Japanese government bond market, rising to 60pc by 2019. Whether such central bank adventurism is a free lunch remains to be seen. There is no sign yet of an inflationary 'pay-back', the moment when the chickens come home to roost. Japan can borrow for fifteen years at minus 0.05pc. My own view - not yet with full conviction - is that global growth will accelerate in the second half. The Fed's retreat from four rate rises this year has been a powerful tonic for emerging markets, while there is still enough fiscal stimulus in the pipeline to keep China's mini-boom going for a few more months. You can see the largesse in the global money supply figures. Simon Ward from Henderson Global Investors says his key measure - six-month real M1 money - is rising at a rate of 10.5pc, the fastest since the post-Lehman stimulus. It is a torrid pace even if you adjust for the declining velocity of money. The figure for China is an explosive 45pc (six-months annualized). Sooner or later, this surge of liquidity will lead to flickerings of inflation in the US, and then to the time-honoured inflationary take-off as the labour market tightens, at which point the markets will react and the global asset rally will short-circuit. The Atlanta Fed's gauge of 'sticky price inflation' for the US is running at 2.8pc. Wage growth has picked up to 2.6pc. Employers are having more trouble finding workers than at the peak of the last two booms. We are not at the danger line yet, but we are getting closer. Brexit was always a hoax for world markets. The financial cycle will end as it always has in peacetime over the last century: when the Fed tightens. "We suspect that an abrupt reassessment of the outlook for US monetary policy remains the key risk," says Capital Economics. Precisely. by Jeff Cox

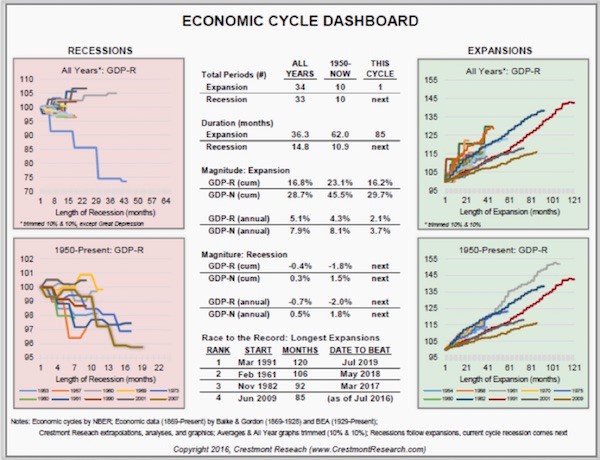

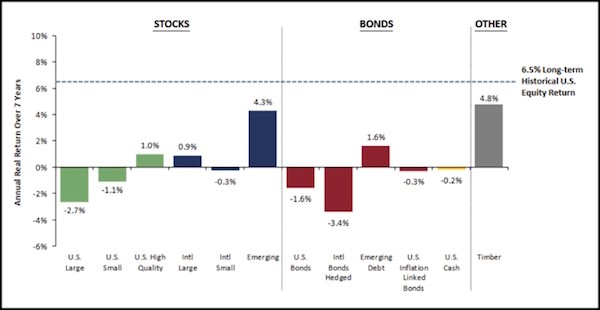

CNBC July 20, 2016 Corporate debt is projected to swell over the next several years, thanks to cheap money from global central banks, according to a report Wednesday that warns of a potential crisis from all that new, borrowed cash floating around. By 2020, business debt likely will climb to $75 trillion from its current $51 trillion level, according to S&P Global Ratings. Under normal conditions, that wouldn't be a major problem so long as credit quality stays high, interest rates and inflation remain low, and there are economic growth persists. However, the alternative is less pleasant should those conditions not persist. Should interest rates rise and economic conditions worsen, corporate America could be facing a major problem as it seeks to manage that debt. Rolling over bonds would become more difficult should inflation gain and rates raise, while a slowing economy would worsen business conditions and make paying off the debt more difficult. In that case, a "Crexit," or withdrawal by lenders from the credit markets, could occur and lead to a sudden tightening of conditions that could trigger another financial scare. "A worst-case scenario would be a series of major negative surprises sparking a crisis of confidence around the globe," S&P said in the report. "These unforeseen events could quickly destabilize the market, pushing investors and lenders to exit riskier positions ('Crexit' scenario). If mishandled, this could result in credit growth collapsing as it did during the global financial crisis." In fact, S&P considers a correction in the credit markets to be "inevitable." The only question is degree. The firm worries that investors have been overly willing in their hunt for yield to buy speculative-grade corporate debt. This has been true not only in the United States but also China, which has used borrowing to spur growth but now finds itself at an economic crossroads. Despite the debt boom, central banks have been loathe to put on the brakes. Interest rates remain low around the world, generating a boom in both corporate and government debt, with nearly $12 trillion of the latter now carrying negative yields. "Central banks remain in thrall to the idea that credit-fueled growth is healthy for the global economy," S&P said. "In fact, our research highlights that monetary policy easing has thus far contributed to increased financial risk, with the growth of corporate borrowing far outpacing that of the global economy." Between now and 2020, debt "flow" is expected to grow by $62 trillion — $38 trillion in refinancing and $24 trillion in new debt, including bonds, loans and other forms. That projection is up from the $57 trillion in new flow S&P had expected for the same period a year ago. As the debt market reaches its limits, the firm believes the most likely scenario is an orderly drawdown. However, that projection faces risks. "Alternatively, a worst-case scenario comprising several negative economic and political shocks (such as a potential fallout from Brexit) could unnerve lenders, causing them to pull back from extending credit to higher-risk borrowers," the report said. "Indeed, the credit build-up has generated two key tail risks for global credit. Debt has piled up in China's opaque and ever-expanding corporate sector and in U.S. leveraged finance. We expect the tail risks in these twin debt booms to persist." There's a significant risk in credit quality. Close to half of companies outside the financial sector are considered "highly leveraged," which is the lowest category for risk, and up to 5 percent of that group has negative earnings or cash flows. There already have been 100 debt defaults in 2016, the most since the financial crisis for the period. S&P worries that investors, particularly those that have bought bonds with longer duration in an effort to get higher yield, are at risk. "Favorable financing conditions, such as abundant debt funding and low interest rates, have elevated prices for financial assets as investors searched for yield," the report said. "This creates conditions for greater market volatility over the next few years due to lower secondary-market liquidity, with credit spreads for riskier credits and longer duration assets being most exposed." China is expected to account for the bulk of the credit flow growth, with the nation projected to add $28 trillion or 45 percent of the $62 trillion expected global demand increase. The U.S. is estimated to add $14 trillion or 22 percent, with Europe adding $9 trillion, or 15 percent. by John Mauldin July 16, 2016 The Age of No Returns The enemy is coming. Having absorbed Japan to the west and Europe to the east, negative interest rates now threaten North America from both directions. The vast oceans that protect us from invasions won’t help this time. Someday I want to get someone to count the number of times I’ve mentioned central bank chiefs by name in this newsletter since I first began writing in 2000, and we should graph the mentions by month. I suspect we’ll find that the number spiked higher in 2007 and has remained at a high plateau ever since – if it has not climbed even higher. That’s our problem in a nutshell. We shouldn’t have to talk about central banks and their leaders every time we discuss the economy. Monetary policy is but one factor in the grand economic equation and should certainly not be the most important one. Yet the Fed and its fellow central banks have been hogging center stage for nearly a decade now. That might be okay if their policies made sense, but abundant evidence says they do not. Overreliance on low interest rates to stimulate growth led our central bankers to zero interest rates. Failure of zero rates led them to negative rates. Now negative rates aren’t working, so their ploy is to go even more negative and throw massive quantitative easing and deficit financing at the balky global economy. Paul Krugman is beating the drum for more radical Keynesianism as loudly as anyone. He has a legion of followers. Unfortunately, they are in control in the halls of monetary policy power. Our central banks are one-trick ponies. They do their tricks well, but no one is applauding, except the adherents of central bank philosophy. Those of us who live in the real economy are growing increasingly restive. Today we’ll look at a few of the big problems that the Fed and its ilk are creating. As you’ll see, I think we are close to the point in the US where a significant course change might help, because our fate is increasingly locked in. I believe Europe and Japan have passed the point of no return. That means we should shift our thinking toward defensive measures. The Big Conundrum The immediate Brexit shock is passing, for now, but Europe is still a minefield. The Italian bank situation threatens to blow up into another angry stand-off like Greece, with much larger amounts at stake. The European Central Bank’s grand plans have not brought Southern Europe back from depression-like conditions. I cannot state this strongly enough: Italy is dramatically important, and it is on the brink of a radical break with European Union policy that will cascade into countries all over Europe and see them going their own way with regard to their banking systems. Italian politicians cannot allow Italian citizens to lose hundreds of billions, if not trillions, of euros to bank “bail-ins.” Such losses would be an utter disaster for Italy, resulting in a deflationary depression not unlike Greece’s. Of course, for the Italians to bail out their own banks, th ey will have to run their debt-to-GDP ratio up to levels that look like Greece’s. Will the ECB step in and buy Italy’s debt and keep their rates within reason? Before or after Italy violates ECB and EU policy? The Brexit vote isn’t directly connected to the banking issue, but it is still relevant. It has emboldened populist movements in other countries and forced politicians to respond. The usual Brussels delay tactics are losing their effectiveness. The associated uncertainty is showing itself in ever-lower interest rates throughout the Continent. That’s the situation to America’s east. On our western flank, Japan had national elections last weekend. Voters there do not share the anti-establishment fever that grips the rest of the developed world. They gave Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his allies a solid parliamentary majority. Japanese are either happy with the Abenomics program or see no better alternative. His expanded majority may give Abe the backing he needs to revise Japan’s constitution and its official pacifism policy. Doing so would be less a sign of nationalism than a new economic stimulus tool. Defense spending that more than doubles – as it is expected to do – will give a major boost to Japan’s shipyards, vehicle manufacturing, and electronics industries. The Bank of Japan’s negative-rate policy and gargantuan bond-buying operation will now continue full force and may even grow. Whether the program works or not is almost beside the point. It shows the government is “doing something” and suppresses the immediate symptoms of economic malaise. The Bank of Japan is the Japanese bond market. They are buying everything that comes available, and this year they will need to cough up an extra ¥40 trillion ($400 billion) just to make their purchase target, let alone increase their quantitative easing in the desperate attempt to drive up inflation. What is happening is that foreign speculators are becoming some of the largest holders of Japanese bonds, and many Japanese pension funds and other institutions are required to hold those bonds, so they aren’t selling. The irony is that the government is producing only about half the quantity of bonds the Bank of Japan wants to buy. Sometime this year the BOJ is going to have to do something differently. The question is, what? Okay, for you conspiracy theorists, please note that “Helicopter Ben” Bernanke was just in Japan and had private meetings with both Prime Minister Abe and Kuroda, who heads the Bank of Japan. Given the limited availability of bonds for the BOJ to buy, and that they’ve already bought a significant chunk of equities and other nontraditional holdings for a central bank, what are their other options? Perhaps Japan could authorize the BOJ to issue very-low-interest perpetual bonds to take on a significant portion of the Japanese debt. That option has certainly been a topic of discussion. It’s not exactly clear how you get people to give up their current debt when they don’t want to, or maybe the BOJ just forces them to swap out their old bonds for the new perpetual bonds, which would be on the balance sheet of the Bank of Japan and not counted as government debt. That’s one way to get rid of your debt problem. But that doesn’t give Abe and Kuroda the inflation they desperately want. Putting on my tinfoil hat (Zero Hedge should love this), the one country that could lead the way in actually experimenting with a big old helicopter drop of money into individual pockets is Japan. And Ben was just there… This bears watching. Okay, I am now removing my tinfoil hat. Yellen Changes the NIRP Tune I have been saying on the record for some time that I think it is really possible that the Fed will push rates below zero when the next recession arrives. I explained at length a few months ago in “The Fed Prepares to Dive.” In that regard, something important happened recently that few people noticed. I’ll review a little history in order to explain. In Congressional testimony last February, a member of Congress asked Janet Yellen if the Fed had legal authority to use negative interest rates. Her answer was this: In the spirit of prudent planning we always try to look at what options we would have available to us, either if we needed to tighten policy more rapidly than we expect or the opposite. So we would take a look at [negative rates]. The legal issues I'm not prepared to tell you have been thoroughly examined at this point. I am not aware of anything that would prevent [the Fed from taking interest rates into negative territory]. But I am saying we have not fully investigated the legal issues. So as of then, Yellen had no firm answer either way. A few weeks later she sent a letter to Rep. Brad Sherman (D-CA), who had asked what the Fed intended to do in the next recession and if it had authority to implement negative rates. She did not directly answer the legality question, but Bloomberg reported at the time (May 12) that Rep. Sherman took the response to mean that the Fed thought it had the authority. Yellen noted in the letter that negative rates elsewhere seemed to be having an effect. (I agree that they are having an effect; it’s just that I don’t think the effect is a good one.) Fast-forward a few more weeks to Yellen’s June 21 congressional appearance. She took us further down the rabbit hole, stating flatly that the Fed does have legal authority to use negative rates, but denying any intent to do so. “We don't think we are going to have to provide accommodation, and if we do, [negative rates] is not something on our list,” Yellen said. That denial came two days before the Brexit vote, which we now know from FOMC minutes had been discussed at a meeting the week earlier. But I’m more concerned about the legal authority question. If we are to believe Yellen’s sworn testimony to Congress, we know three things: 1. As of February, Yellen had not “fully investigated” the legal issues of negative rates. 2. As of May, Yellen was unwilling to state the Fed had legal authority to go negative. 3. As of June, Yellen had no doubt the Fed could legally go negative. When I wrote about this back in February, I said the Fed’s legal staff should all be disbarred if they hadn’t investigated these legal issues. Clearly they had. Bottom line: by putting the legal authority question to rest, the Fed is laying the groundwork for taking rates below zero. And I’m sure Yellen was telling the truth when she said last month that they had no such plan. Plans can change. The Fed always tells us they are data-dependent. If the data says we are in recession, I think it is very possible the Fed will turn to negative rates to boost the economy. Except, in my opinion, it won’t work. When Average Is Zero Now, I am not suggesting the Fed will push rates negative this month or even this year – but they will do it eventually. I’ll be surprised if it doesn’t happen by the end of 2018. A prime reason the next recession will be severe is that we never truly recovered from the last one. My friend Ed Easterling of Crestmont Research just updated his Economic Cycle Dashboard and sent me a personal email with some of his thoughts. Here is his chart (click on it to see a larger version). The current expansion is the fourth-longest one since 1954 but also the weakest one. Since 1950, average annual GDP growth in recovery periods has been 4.3%. This time around, average GDP growth has been only 2.1% for the seven years following the Great Recession. That means the economy has grown a mere 16% during this so-called “recovery” (a term Ed says he plans to avoid in the future). If this were an average recovery, total GDP growth would have been 34% by now instead of 16%. So it’s no wonder that wage growth, job creation, household income, and all kinds of other stats look so meager. For reasons I have outlined elsewhere and will write more about in the future, I think the next recovery will be even weaker than the current one, which is already the weakest in the last 60 years – precisely because monetary policy is hindering growth. Now combine a weak recovery with NIRP. If, in the long run, asset prices are a reflection of interest rates and economic growth, and both those are just slightly above or below zero, can we really expect stocks, commodities, and other assets to gain value? The upshot is that whatever traditional investment strategy you believe in will probably stop working soon. Ask European pension and insurance companies that are forced to try to somehow materialize returns in a non-return world of negative interest rates. All bets may be off anyway if the latest long-term return forecasts are correct. Here’s GMO’s latest 7-year asset class forecast: See that dotted line, the one that not a single asset class gets anywhere near? That’s the 6.5% long-term stock return that many supposedly wise investors tell us is reasonable to expect. GMO doesn’t think it’s reasonable at all, at least not for the next seven years.

If GMO is right – and they usually are – and you’re a devotee of any kind of passive or semi-passive asset allocation strategy, you can expect somewhere around 0% returns over the next seven years – if you’re lucky. Note also that nearly invisible -0.2% yellow bar for “U.S. Cash.” Negative multi-year real (adjusted for inflation) returns from cash? You bet. Welcome to NIRP, American-style. Would you like that with fries? The Fed’s fantasies notwithstanding, NIRP is not conducive to “normal” returns in any asset class. GMO says the best bets are emerging-market stocks and timber. Those also happen to be thin markets that everyone can’t hold at once. So, prepare to be stuck. by George Friedman

Geopolitical Futures July 8, 2016 The Italian banking crisis is not only Italy’s problem. We are now at the point where the mainstream media has recognized that there is an Italian banking crisis. As we have been arguing since December, when we published our 2016 forecast, Italy’s crisis will be a dominant feature of the year. Italy has actually been in a crisis for at least six months. This crisis has absolutely nothing to do with Brexit, although opponents of Brexit will claim it does. Even if Britain had unanimously voted to stay in the EU, the Italian crisis would still have been gathering speed. The extraordinarily high level of non-performing loans (NPLs) has been a problem since before Brexit, and it is clear that there is nothing in the Italian economy that will allow it to be reduced. A non-performing loan is simply a loan that isn’t being repaid according to terms, and the reason this happens is normally the inability to repay it. Only a dramatic improvement in the economy would make it possible to repay these loans, and Europe’s economy cannot improve drastically enough to help. We have been in crisis for quite a while. The crisis was hidden, in a way, because banks were simply carrying loans as non-performing that were actually in default and discounting the NPLs rather than writing them off. But that simply hid the obvious. As much as 17 percent of Italy’s loans will not be repaid. As a result, the balance sheets of Italian banks will be crushed. And this will not only be in Italy. Italian loans are packaged and resold as others, and Italian banks take loans from other European banks. These banks in turn have borrowed against Italian debt. Since Italy is the fourth largest economy in Europe, this is the mother of all systemic threats. Since the problem is insoluble, the only way to help is a government bailout. The problem is that Italy is not only part of the EU, but part of the eurozone. As such, its ability to print its way out of the crisis is limited. In addition, EU regulations make it difficult for governments to bail out banks. The EU has a concept called a bail-in, which is a cute way of saying that the depositors and creditors to the bank will lose their money. This is what the EU imposed on Cyprus. In Cyprus, deposits greater than 100,000 euros ($111,000) were seized to cover Cypriot bank debts. While some was returned, most was not. The depositors discovered that the banks, rather than being a safe haven for money, were actually fairly risky investments. The bail-in is, of course, a formula for bank runs. The money seized in Cyprus came from retirement funds and bank payrolls. The Italian government is trying to make certain that depositors don’t lose their deposits because a run on the banks would guarantee a meltdown. A meltdown would topple the government and allow the Five Star Movement, an anti-European party, a good shot at governing. The reason for the bail-in rule is Berlin’s aversion to bailing out banking systems using German money. Germany is already seeing a rise in anti-European political feeling with the rising popularity of the nationalist Alternative for Germany party. Unlike Italian anti-European sentiment, the German sense of victimization is their perception that they are disciplined and responsible, and they resent paying for the irresponsibility of others. Therefore, the German government’s hands are tied. It cannot accept a Europe-wide deposit insurance system as it would put German money at risk, nor can it permit the euro to be printed promiscuously, as that would come out of the German hide as well. The Italians can only try and manage the problem by ignoring EU rules, which is what they are actually doing. But there is another European economic crisis brewing. As we have pointed out, Germany derives nearly half of its GDP from exports. All the discipline and frugality of the Germans can’t hide the fact that their prosperity depends on their ability to export and that the ability to export depends on the effective demand of their customers. Germany exports heavily to the EU, and the Italian crisis, if it proceeds as it is going, is likely to cause an EU-wide banking crisis, and an even greater weakening of the European economy. That would cut deeply into German exports, slashing GDP and inevitably driving up unemployment. Logic would have it that the Germans are acting desperately to head off an Italian default, but Chancellor Angela Merkel has built her government on Germany’s pride in its economy. She is not eager to announce to the German people that the German economy depends on Italy’s well-being. But it is clear that German businesses are aware of the danger. German production of capital goods fell nearly 4 percent from last month, and German production of consumer goods rose only 0.5 percent. German consumption can’t possibly make up for half of Germany’s GDP. In addition, the International Monetary Fund has recently pointed to Deutsche Bank as the single largest contributor to systemic risk in the world. A rippling default through Europe is going to hit Deutsche Bank. However, the real threat to Germany is a U.S. recession. Recessions are normal, cyclical events that are necessary to maintain economic efficiency by culling inefficient businesses. The U.S. has one on average once every six to seven years. Substantial irrationality has crept into the economy, including new bubbles in housing. The yield curve on interest rates is beginning to flatten. Normally, a major market decline precedes a recession by three to six months. That would indicate that there likely won’t be a recession in 2016 but there is a reasonable chance of one in 2017. Given the stagnation in Europe, Germany has been shifting its exports to other countries, particularly the United States. It is hard to tell how much price cutting the Germans had to do to increase their exports, but it has been useful to maintain the amount of GDP derived from exports. If the United States goes into recession, demand for German goods, among others, will drop. But in the case of Germany, a 1 percent drop in exports is nearly a half percent drop in GDP. And given Germany’s minimal growth rate, drops of a few percentage points could drive it not only into recession, but into its primordial fear: high unemployment. A U.S. recession would not only hit the Germans, but the rest of Europe, which also exports to the United States, either directly or through producing components for German and British products. When we look at data on U.S. exposure to foreign debt defaults, there is some, but not enough to bring down the American system. The United States, with relatively low export percentages and low exposure, can withstand its cycle. It is not clear that Europe can. Compounding this problem is an ever-increasing number of non-performing loans in China. Most of these are domestic loans, but they reflect the fact that China has never recovered from the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. It has avoided massive social dislocation by encouraging loans to businesses of all sizes and dubious viability in order to maintain employment as far as possible. There is a new wave of non-performing loans coming due. And as with Italy, non-performing is a euphemism. The problem is not that these loans are late. The problem is that they were loaned to businesses and individuals who should have been forced out of business by a lack of credit, and were kept alive on artificial respirators. The obsession of figures like European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, railing against Brexit, was not a smokescreen. He and others really did see Brexit as the major danger to the EU. That is what is most troubling. Far more significant are Italy’s financial crisis and Germany’s extreme vulnerability. Whether the British stay or go, Italy’s and Germany’s problems have to be addressed, and the existence of the EU and its regulations make finding solutions extremely difficult. This all was put in motion in 2008, but it is not a 2008 crisis. This is most of all a political and administrative crisis caused by a European system that was created to administer peace and prosperity, not to manage the complex gyrations of an economy. Similarly, China introduced the doctrine of enriching yourself to please the Party, but hadn’t considered what to do when the party was over. The argument from those who are against internationalism is simple. Sometimes the major international systems begin failing. The less you are entangled with these systems the less damage is done to you. And given that such systemic failures historically lead to international political conflict and crisis, the case for nationalism increases – assuming you aren’t already trapped in the systemic crisis. In any event, increasing nationalism follows systemic failure like night follows day. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed