|

by Nicholas Colas, Chief Market Strategist

Convergex May 2, 2017 “It’s quiet out there… too quiet.” That old line, its origins lost to history, neatly sums up how many equity traders feel right now. Global equities continue their remarkable rally in the most unremarkable of ways. Slow, and steady and boring. The CBOE VIX Index briefly broke 10 today, essentially half of its long run average of 19.6, and closed at 10.11. In its unofficial role as the primary forecasting tool of near term US equity volatility, that is the equivalent of a Los Angeles weather forecast. 80 degrees and sunny… Next weather update in 5 days. I got to wondering just how many days the VIX has closed below 10 and what that means for future equity returns. The answers:

The takeaway from these examples is clear: in the unusual instances (just 0.13% of the days since 1990) when the VIX closes below 10, one year forward returns have all been negative. In one case (2007 into 2008) the following year was terrible. In the other case (1994 into 1995) it was great – up 37.2%. If you want to see a history of S&P 500/3 month T-bills/10 year Treasury note returns (very useful when looking at historical trends such as these), click here: http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/histretSP.html Important: the upshot of this quick analysis is this: a VIX close below 10 is historically correlated with a one year pause in S&P 500 returns. The year after that is where things get dicey. You could get a 1995 (+37%) or a 2008 (down 37%). Now, 3 (2 and half, if we’re being honest) examples isn’t a great sample size. To round out the discussion we need to come to some conclusions about WHY US equity volatility is so low. And what might change that. Here are 10 equity “Puts”: commonly held investor beliefs about current market dynamics that help explain both low volatility and the march higher for US and global equities. #1) The Fed Put. Ever since Alan Greenspan came to the US equity market’s rescue after the October 1987 crash, there has been a school of thought that says the US Federal Reserve views equity markets as a “Third mandate” along with price stability and full employment. If markets falter, the Fed will pass on a June rate increase and perhaps those scheduled for later in the year as well. Or so the logic goes… #2) The ECB Put. To the degree to which the European Central Bank has mimicked the Fed’s policies of ultralow interest rates and the purchase of long dated bonds (quantitative easing), equity investors may well feel that there is also an ECB “Put”. #3) “Long End of the Yield Curve” Put. If global economic growth is about to take a step function higher (as indicated by rallies in US, EAFE and Emerging Market equities) no one seems to have told sovereign debt markets. The US 10 year note for example, yields all of 2.3% and the 10 year German Bund pays a 0.3% coupon. Those low rates help support equity valuations, and if global growth falters those rates will go lower still (and continue to help valuations). #4) “Trump/Republican Washington” Put. At some point before the mid-term US elections in 2018, President Trump and the GOP – controlled Congress should be able to pass tax reform. That gives equity investors the chance to see earnings estimates rise for 2018 and beyond, supporting current valuations. #5) “Passive Money/ETF Flow” Put. Year to date money flows into equity US listed Exchange Traded Funds total $121 billion, a pace that will break all prior records if it continues through the end of 2017. Moreover, those flows are remarkably consistent whether you look at the last day, week, month, quarter to date or calendar year. As long as those trends continue, why worry about a market correction? #6) “Offshore/Corporate Cash” Put. US public companies continue to operate at near-record profit margins, but they are still more likely to buy back their own stock or hold cash offshore rather than invest in their business with those cash flows. That leaves them less prone to financial stress during an economic downturn and therefore reduces their stock price volatility across the business cycle. Also worth considering: if corporate tax reform does come through, these same companies may be able to repatriate some of their offshore cash holdings for buybacks (which would also reduce price volatility, everything else equal). #7) “Lower Sector Correlation” Put. Since the November US elections, sector correlations within the S&P 500 have dropped from +90% to 55-60%. Should this continue (and absent a major correction, it should), overall S&P 500 volatility will remain lower than when correlations were higher. #8) “Earnings Beats GDP” Put. As it stands right now, the S&P 500 will post close to a 10% earnings growth rate for Q1 2017. Part of that is from smaller losses in the Energy sector, and part is actual earnings growth in Financials, Materials, and Tech stocks. All of it is enough to allow analysts to expect Q2 2017 earnings growth to run 8%, even though Q1 US GDP growth only showed 0.7% growth when it was released last Friday. #9) “Receding Nationalism” Put. Now that equity investors seem certain Marine Le Pen will not be the next French president, the prospects for a “Frexit” seem distant. Polls currently have her at 40% of the vote versus Macron’s 60%. See here for a good poll tracker: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-39692961 #10) “GDP Bounce Back” Put. After a lackluster Q1 GDP print, the closely watched (and accurate for Q1) Atlanta Fed GDP Now model has a 4.3% starting estimate for Q2 2017. Blue chip economists are sitting closer to 2.7%, but all agree for the moment that Q2 will be far better than Q1. I could go on, but you get the point: there is an overwhelming market narrative that equates to “Don’t worry, be happy”. That should be no surprise. You don’t end up with a 10 handle VIX very often, and when you do it is the result of a unique set of circumstances. I will close where I began, with the possibility of a single digit VIX reading. Historically, that signals the possibility of a pause in equity returns. This means at least a few of our 10 “Puts” will not actually work as anticipated. But the real question is not 2017 – it is 2018. Will next year resemble 1995 (+37%) or 2008 (-37%). Again, that comes down to how many of these “Puts” survive the next 12 months. by Danielle DiMartino Booth

April 26, 2017 How do you take your plaque? C’mon, we all have our victual vices that risk turning the gourmet in us gourmand. Those naughty nibbles that do so tempt us. Is it a bacon, cheese, well…anything? Maybe a slice of pie – pizza or otherwise? Or do you take yours scattered, smothered and covered? As in how you order your late-night hashbrowns at Waffle House – scattered on the grill, smothered with onions and covered with melted cheese. That last order is sure to do the trick if clogging your arteries is your aim. Too exhausted to trek inside? Hit the drive through. It’s the American way. Enter Morgan Spurlock. In 2003, he had grown so alarmed with the ease with which we can go from medium to jumbo (in girth) he conducted a filmed experiment. For 30 days, Spurlock consumed his three squares at McDonald’s, a neat average of 5,000 calories a day, twice what’s recommended for a man to maintain his body weight. Fourteen months later, Spurlock managed to shed the 24 pounds he’d packed on. Released in 2004, Super Size Me garnered the nomination for Best Documentary Feature. And since then? A freshly released paper finds that more than 30 percent of Americans were obese in 2015 compared with 19 percent in 1997. Of those who were overweight or obese, about 49 percent said they were trying to lose weight, compared to 55 percent in 1994. One must ask, where’s that “Can Do!” spirit? Why acquiesce given the known benefits of restraint? Perhaps we’d be just as well off asking that same question of the world’s central bankers who seem to have also thrown in the towel on discipline, opting to Super Size their collective balance sheet, the known hazards be damned. At the opposite end of the over-indulge-me spectrum sits one Harvey Rosenblum, a central banker and my former mentor who sought to push his own discipline to the limits throughout his 40 years on the inside, to take a stand against the vast majority of his peers. Consider the paper, co-authored with yours truly, released in October 2008 — Fed Intervention: Managing Moral Hazard in Financial Crises. In the event your memory banks have been fully withdrawn to a zero balance, October 2008 is the month that followed the magnificent dual implosions of Lehman Brothers and AIG. To speak of insurers and quote from our paper: “Moral hazard, a term first used by the insurance industry, captures the unfortunate paradox of efforts to mitigate the adverse consequences of risk: They may encourage the very behaviors they’re intended to prevent. For example, individuals insured against automobile theft may be less vigilant about locking their cars because losses due to carelessness are partly borne by the insurance company.” As it pertains to central banking, we had this to say: “Lessening the consequences of risky financial behavior encourages greater carelessness about risk down the road as investors come to count on benign intervention. By intervening in a financial crisis, the Fed doesn’t allow markets to play their natural role of judge, jury and executioner. This raises the specter of setting a dangerous precedent that could prompt private-sector entities to take additional risk, assuming the Fed will cushion the impact of reckless decision-making.” What a redeeming difference eight years can make? If you’ve read Fed Up, you’ll recognize these words, which open Chapter One: “Never in the field of monetary policy was so much gained by so few at the expense of so many.” Every chapter of the book begins with a quote, most of them ill-fated words straight out the mouths of Greenspan, Bernanke and Yellen, chief architects of the sad paradox that’s benefitted “so few.” Those prescient words were written in November 2015 by Bank of America ML’s Chief Investment Strategist Michael Hartnett, before Brexit was on the tips of any of our tongues, before the anger of the “many” erupted at voting booths. Chapter One goes on to recount the Federal Reserve’s December 2008 decision to lower interest rates to zero. According to the Bernanke Doctrine, the Fed’s purchasing securities, quantitative easing (QE) could not commence until interest rates had hit their lower bound. To suggest the chairman’s blueprint was arbitrary requires a vivid imagination. Few appreciate the Doctrine was conceived in August 2007 in Jackson Hole, in the tight company of his chief architects. But one can breathe a sigh of relief his models did not necessitate negative interest rates. We know it’s been over two years since the Federal Reserve stopped growing its balance sheet to its current $4.5 trillion size. And yet, investors are anything but alarmed, comforted in their knowledge that Liberty Street stretches round the globe. There are plenty of corners on which moral hazard dealers can ply their wares, luring animal spirits out of their lairs. QE is global, it’s fungible and it feels so good. As Hartnett reminds us in his latest dispatch, global QE is, “the only flow that matters.” Add up the furious flowage and you arrive at a cool $1 trillion central banks have bought thus far this year (note: it’s April). That works out to a $3.6-trillion annualized rate, the most in the decade that encompasses the years that made the financial crisis “Great.” “The ongoing Liquidity Supernova is the best explanation why global stocks and bonds are both annualizing double-digit gains year-to-date despite Trump, Le Pen, China, macro…” As so many sailors fated to crash onto the rocky shores of Sirenuse, investors have complied with central bankers’ biddings. And why shouldn’t they? As Bernanke himself wrote in defense of QE in a 2010 op-ed, “Higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending. Increased spending will lead to higher incomes and profits that, in a virtuous circle, will support further economic expansion.” What a relief! This won’t end as tragically as the Greeks would deem fit. It’s the wealth effect, a different myth altogether, protected by virtue herself. Investors are excelling at obedience in such rude form they’ve plowed fresh monies into emerging market debt funds for 12 weeks running. As for stocks, forget the fact that it’s a handful (actually two hands) of stocks that are responsible for half the S&P 500’s gains. Passive is hot, red hot. According to those at Bernstein toiling away at tallying, within nine months more than half of managed US equities will be managed passively. As if to celebrate this milestone, Hartnett reports that an ETF ETF has completed its launch sequence. What better way to mark a decade that’s seen $2.9 trillion flow into passive funds and $1.3 trillion redeemed from active managers? In the event you too need a definition, an ETF ETF is comprised of stocks of the companies that have driven the growth of the Exchange Traded Funds industry. But of course. In the event you’re unnerved by the abundance of blind abandon in our midst, it helps to recall the beauty of moral hazard. Central bankers know what they’re doing in encouraging moral hazard and they’ve got your back. If they can’t prevent, they can at least mitigate the future economic damage they’re manufacturing. As Bernanke said in a 2010 interview, “if the stock market continues higher it will do more to stimulate the economy than any other measure.” If that was true then, isn’t it even truer today? More has to be more. Why diet when it’s so much more satisfying to indulge to our heart (attack’s) abandon? by Katherine Burton and Katia Porzecanski

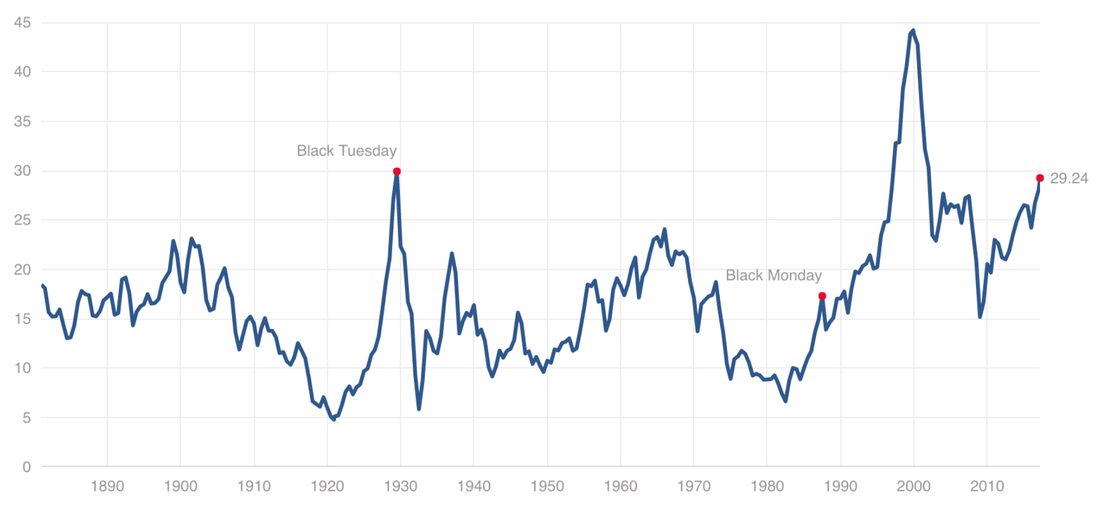

Bloomberg Markets April 21, 2017 Billionaire investor Paul Tudor Jones has a message for Janet Yellen and investors: Be very afraid. The legendary macro trader says that years of low interest rates have bloated stock valuations to a level not seen since 2000, right before the Nasdaq tumbled 75 percent over two-plus years. That measure -- the value of the stock market relative to the size of the economy -- should be “terrifying” to a central banker, Jones said earlier this month at a closed-door Goldman Sachs Asset Management conference, according to people who heard him. Jones is voicing what many hedge fund and other money managers are privately warning investors: Stocks are trading at unsustainable levels. A few traders are more explicit, predicting a sizable market tumble by the end of the year. Last week, Guggenheim Partner’s Scott Minerd said he expected a "significant correction" this summer or early fall. Philip Yang, a macro manager who has run Willowbridge Associates since 1988, sees a stock plunge of between 20 and 40 percent, according to people familiar with his thinking. Even Larry Fink, whose BlackRock Inc. oversees $5.4 trillion mostly betting on rising markets, acknowledged this week that stocks could fall between 5 and 10 percent if corporate earnings disappoint. Caution Flags Their views aren’t widespread. They’ve seen the carnage suffered by a few money managers who have been waving caution flags for awhile now, as the eight-year equity rally marched on. But the nervousness feels a bit more urgent now. U.S. stocks sit about 2 percent below the all-time high set on March 1. The S&P 500 index is trading at about 22 times earnings, the highest multiple in almost a decade, goosed by a post-election surge. Managers expecting the worst each have a pet harbinger of doom. Seth Klarman, who runs the $30 billion Baupost Group, told investors in a letter last week that corporate insiders have been heavy sellers of their company shares. To him, that’s “a sign that those who know their companies the best believe valuations have become full or excessive." He also noted that margin debt -- the money clients borrow from their brokers to purchase shares -- hit a record $528 billion in February, a signal to some that enthusiasm for stocks may be overheating. Baupost was a small net seller in the first quarter, according to the letter. Another multi-billion-dollar hedge fund manager, who asked not to be named, said that rising interest rates in the U.S. mean fewer companies will be able to borrow money to pay dividends and buy back shares. About 30 percent of the jump in the S&P 500 between the third quarter of 2009 and the end of last year was fueled by buybacks, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The manager says he has been shorting the market, expecting as much as a 10 percent correction in U.S. equities this year. China Slowdown Other worried investors, like Guggenheim’s Minerd, cite as potential triggers President Donald Trump’s struggle to enact policies, including a tax overhaul, as well as geopolitical risks. Yang’s prediction of a dive rests on things like a severe slowdown in China or a greater-than-expected rise in inflation that could lead to bigger rate hikes, people said. Yang didn’t return calls and emails seeking a comment. Even billionaire Leon Cooperman -- long a stock bull -- wrote to investors in his Omega Advisors that he thinks U.S. shares might stand still until August or September, in part because of flagging confidence in the so-called Trump reflation trade. But he said that they will eventually resume their climb and end the year moderately higher. Likely Culprit While Jones, who runs the $10 billion Tudor Investment hedge fund, is spooked, he says it’s not quite time to short. He predicts that the Nasdaq, which has already rallied almost 10 percent this year, could edge higher if nationalist candidate Marine Le Pen loses France’s presidential election next month as expected. Jones tripled his money in 1987 in large part by correctly calling that October’s market crash. While the billionaire didn’t say when a market turn might come, or what the magnitude of the fall might be, he did pinpoint a likely culprit. Just as portfolio insurance caused the 1987 rout, he says, the new danger zone is the half-trillion dollars in risk parity funds. These funds aim to systematically spread risk equally across different asset classes by putting more money in lower volatility securities and less in those whose prices move more dramatically. Because risk-parity funds have been scooping up equities of late as volatility hit historic lows, some market participants, Jones included, believe they’ll be forced to dump them quickly in a stock tumble, exacerbating any decline. “Risk parity,” Jones told the Goldman audience, “will be the hammer on the downside.” by Latha Venkate

CNBC March 28,, 2017 In an interview to CNBC-TV18's Latha Venkatesh, Nassim Taleb, Statistician & Author of The Black Swan spoke about global economy and other related issues. Q: Let me start with an autobiographical question - you are one of those rare people who profited in the 1987 crash and in the 2007 crisis as well. Can you tell us something about what made you see this crisis coming and how did you profit from them? A: The first thing is that prediction is a wrong word because in a risk domain we do not talk of prediction. We talk about detection of fragility, so you have to detect what is fragile. If something is fragile eventually it is going to break. You can easily forecast that the coffee cup you have on a table is not going to outlive the table except maybe in rare circumstances. You can safely say that a pilot who is not very good at understanding storms eventually is going to have a funeral. So it's not forecasting; it is to understand what is fragile and what is not. So the first statement is to understand a fragile. The second thing, something that is fragile in a local way that's been your constraint, something systemic are fragile and these collapse. The crisis of 1987 had no idea about fragility. It's about 30 years ago and I was a trader, by then I was making bets on extreme events but some people substitute their own judgement that of others, but that I didn't take the answer and I said I am going to buy every single option I can. So before '87 there was Plaza Accord in '86 in which the market moved big time in currencies and we thought we are going to make little bit money - that was a business to me and so that is what happened to me. So there are two stories in there and actually reflected into my book - The Black Swan is about the incidence of these events and some domains. So basically what we have to do is to identify the domain in which it can happen. We know that 20 million people killed and penalty will happen to every 10 to 100, which we should basically never, whereas Ebola is more likely to do that. Therefore, identify the domain and second is identify the fragility. The two combined are crisis of 2008. For crisis of 2008, I was much more prepared. I was more comfortable and had written The Black Swan and I was completely depressed by the interpretation of my ideas about The Black Swan - it really got the point, as they said let's forecast -- that is not our work; detect fragility and the system was very fragile and it was described in The Black Swan as being fragile. So I came back. I thought I was done with trading, you cannot trade for too long, it becomes too stressful. You need time to recover of any activity and trading doesn't allow you that, you always have chronic stress. A chronic stress for 24 years was too much for me but then I started to come back, so I came back. So this is my autobiography. I then wanted to back out of the market. I wanted to be a scholar and initially I got into market not because of any economic reason or anything. I thought it was fun. It was really a fun to trade; trading is a lot of fun and it is like playing for living. So I did that and I got addicted to it. Q: Since you were once addicted to trading and even though now you are more a full time scholar than a trader, I do want to ask you where you see the top risk today or the top three risks today; after all we have seen a fairly decent Trump rally. There is a risk on across several financial assets. What would you say are the three big risks? A: The first big risk I see, let's forget about the economy and all that, it is really severe is from the reaction of Ebola. Why did I talk about Ebola because so I can follow-up now on a conversation by telling you what detected is a complete incompetence on a part of US authorities particularly state department in understanding the nature of multiplicative risk. A friend of mine, we analysed the situation and we called up the state department, a friend of mine contacted the state department and he told them every plane that leaves, every person with Ebola will have 500 exposures on a way and we was talking about the plague which was travelling with something like 30 miles a day. This is travelling much faster. These risks you have to recognise and they refused to recognise them and The New York Times published some comment saying it makes no sense to worry about Ebola. It only killed three Americans - this is what I picked up. So the way they reacted to the risks means lack of consciousness on a part of bureaucrats outside Singapore of course; Singapore understand it perfectly that emerging threats when they are systemic and multiplicative, need to be dealt with seriously. And I am afraid that because of antibiotic resistance should we have another plague that would travel very fast. Authorities in the past used to panic very quickly. Today they are talked by the risk management professor who never took risk, never worked for an insurance company, never did anything but these professors of finance for example say don't worry about it, it is statistically rare and stuff like that. So this is what worries me. Q: I must confess I wasn’t prepared for Ebola as an answer. What is the second big risk? A: Second one links to it, it can be used by terrorists. Q: Biological warfare you mean? A: Exactly. This is what we have to worry about, we don’t have to worry about conventional warfare. Of course it is a good idea for some people to convince you of it so they can sell you weapons but we have to worry about biological warfare first. That coupled with terrorism is a serious threat. So, that would be my second one. Now lets us talk finance. We had a crisis due to fragility of the financial system, too much debt, many people who shouldn’t lend were lending and many people who shouldn’t borrow were borrowing. Simple debt cycle that happened to correct like the forests. Forest has fires, clean ups the bad material. They kept perpetuating it with low interest rates under Greenspan. What did the US government do in conjunction with the Federal Reserve and don’t tell me it is independent of the Obama regime. So, what did they do? They kept interest rates very low and they let debt accumulate, transferred from individuals to the public sector, with hidden debt accumulating in form of all of the student loans but then much more seriously our liabilities with social security and all of that. So, now what do we have? We have a huge amount of debt, the government has USD 10 trillion more than it did before and interest rates are zero, so, the government deficit seems to be out of control. What if interest rates rose? Interest rates when they are at zero, first of all it is concave, in other words it is just like any ponzi scheme – you need to do more and more to keep it in place at the end. So, lower interest rates below 3 percent made no sense. Now we have something that is completely ineffective. You can no longer lower rates if you faced any further crisis and the resultant is printing money. So, now what’s the situation we are facing today? It is that we need to raise interest rates back up to normal levels say at least 3 percent. How do you do that? By raising rates. What happens when you raise rates? When you raise rates 0.25 points at a time, it’s not going to work. You are not going to get there. I remember in 1994 when Greenspan abruptly raised rates in United States financial markets did okay but worldwide – oh my god. We had for 2-3 years all this money flowing back to the states. So, we might be faced with a situation of say Tequila sort of crisis, facing the increase of interest rates in United States. Q: The previous hike of the US Federal Reserve did not evoke such strong reactions in financial markets. They were practically very well awaited, people were almost begging for a hike. Do you think things can still get out of hand? Of course Trump is speaking of more debt now – fiscal debt and how do you see therefore bond markets? A: First of all we haven’t seen the effect of last hike. After Greenspan some effects came upto a year later. However we have seen the effects of the monetary policy that we were doing before, inflating asset values. In fact during the Obama regime, it was the most interesting regime where we had stability at the expense of a median income that was increasing and a shift to inequality that was monstrously increasing simply because either people who had assets got richer and also because globalisation took place in that period of time and it had the effect whether we like it or not of causing winner take all effect. We spoke about the three risks, let me tell you what I think is not a risk. What is not a risk is this reaction – the Brexit reaction, the Trump reaction, it is a reaction by the grandmother, saying, there is something we don’t understand. When Nigel Farage speaks, they say I understand it, at least I know if he right or wrong. Whereas with the other guys we don’t know if they are right or wrong. When he went to Brussels, what we had in Europe was a symptomatic effect of last events as a concentration of a class of people who are bureaucrats, who have proved serial incompetence, they are not in business and also because they are not penalised for their mistakes. I don’t know many businesses in which a person making a mistake is not penalised. Whereas there it is completely insulated from that system. So, that class of people, you look at examples of how many documents they have regulating but they can’t control borders, they can’t control anything essential. So, what we have now is divorce between the notion of Europe and bureaucrats of Brussels. Q: Let us talk of the two risks separately. You spoke about Greenspan’s rate hike impact coming in much later. So, you still think that as the Federal Reserve hikes rates, we could still see some fairly drastic impact in financial markets a year down the line? A: The first thing you have to realise is already when you hike rates you are increasing the borrowing cost of the next government which are considerably higher today than they were in the past. 100 basis points is something like several hundred million dollars more. We are talking about increasing USD 53 billion defence spending, we don’t realise that 100 basis points or 200 basis points in expenditure is going to make that look like Friday afternoon pocket money for children. That is one thing you have to worry about. 25 basis points is symbolic and in effect other than US government and banks it doesn’t seem to impact people because nobody is borrowing. The point is only government is the one borrowing. If you look at the health of companies it is a completely different dynamics. Q: Do you think Europe is a big risk? We have got elections in France and Germany also coming up or do you think like Brexit, that is the known risk? A: To me Brexit was good news and effectively, from the beginning - I went on CNBC - before the Brexit, I went before the election of Trump to make sure to make my point is that should Trump be elected for number one, of course, I said it is not necessarily a bad thing that people tell you but that was not Trump that I was plugging. I was plugging the idea that if he is elected, the markets are not going to collapse. Q: I remember, November 3, you said Trump could get elected and he won't be apocalyptic. A: He will not be. Exactly, so stop worrying about this and something tells me that the healthiest Europe is a Europe that is managed by the smallest amount of people in Brussels. Q: You mean the breakup of Europe will not be apocalyptic? A: It is not a breakup. We live in a world of uberising relationships. So if you take the relationships of France with Morocco for example, you don't have to call Brussels to ask him for permission to do something. What is the aim of Europe? First of all, one thing about Europe that few understand that the notion of Europe isn't the classical Europe. That notion of Europe that they have is the Frankish Europe of Aix-la-Chapelle and Aachen and Germany of Charlemagne because the classical Europe is a Mediterranean. It is around the Mediterranean. Q: Closer to your home town? A: So, I am saying the Byzantine, that is a Roman empire, was the Byzantine Empire. So that is a classical Europe and then what you had out there is the rival to Byzantine. When Byzantine was there, these people who called themselves holy roman emperor and they had three things wrong. They were neither holy nor roman, Roman was Byzantium, Constantinople. He was the real emperor. So, the EU may end up and actually Martin Walls has made a similar remark, will end up as some paper organisation where people can go when they are fired from their job or when you want to get rid of them in Paris, you send them to Brussels or it is like sending someone to Coventry. It may survive that way because the holy Roman Empire survived a thousand years doing nothing. So you have to think about it, they had no power. So that is the notion. So you have to separate the idea of Europe and also understand that countries are adults. For example, take the UK. The UK wants, I put the question when I was I think, with David Cameron and he called it slander. I said, who do you identify with? And English speaking Indian person or someone from Poland? Who can you have dinner with? You sit down, you can communicate with someone brought up in Delhi, but you cannot communicate with someone brought up in Krakow. You get the idea? So why are we doing this? So you will say, it is of no European risk. So forget the notion of people being able to do deals together just like United States can do a deal now with Ireland hopefully and the UK where Americans can go work there, they can come work here, you can make agreements. So, you see the idea? So, countries are adults. But Norway and Switzerland, the two most successful countries in Europe are not in the EU. And people then worry about movement of population. Ireland and Cyprus are not in Schengen. So, it is like all these arguments seem to be like someone reacting without having a proper argument, sort of like if a lady goes in and tells her husband, listen I am divorcing you, goodbye. And then he has to come up with 10 arguments immediately, a not very well processed argument. These are the arguments used in favour of EU and against Brexit. I do not see any of them as economically reasonable nor even politically reasonable. The world does not like bureaucrats. Ancient Egypt and China collapsed after they bureaucratised the system. Q: Well that is one worry less. We should not worry about a confederating or perhaps, a splitting Europe. Let me come to India. We just had a gigantic experiment where our government changed 86 percent of the currency. A kind of demonetisation. Did you read about it? Any first comments? We seem to have come out of it with minor bruises. A: My first comment is that whenever economists tell you something is apocalyptic, it is not going to be. So, I do not know if it is good or bad but something was conveyed to me that a friend called me up and said, and actually I came to India right after that. And he said, every single economist said it made no sense, or at least economists that he knew said it made no sense. I said, every single economist said it made no sense, probably it is at least neutral. So, it does not have to be neutral. So, that is my idea. That is only thing I know about it. Now I do not understand the dynamics of what is going on, this I do not understand nor do I need to know. And I do not know much about India. I know stuff about India, but that is not the kind of stuff I understand. Q: I do not know how well you know our Prime Minister, Narendra Modi. He in a sense, single-handedly went into demonetisation. Do you think he is really making India anti-fragile? A: This I am going to tell you what I think I know about India from conversation and from visiting several clients. Every single Indian I meet tells me the same thing. They think that these sectors that do very well are sectors in which the government tried not to improve too much. I believe in government and I have heard Modi saying the government should not do to many things, but what the government does, should do it very well. So that is the idea. That is what I heard. But the problem is again to destroy the crust of people who make life difficult for others while genuinely thinking they are improving the system and reallocating. And the other thing is the first thing and it looks like it is part of the programme. Now in two years, I do not know how much was done in reducing the role of these things and hindering rather than advancing. And the second point that there was some element of decentralisation floating. And I think the decentralisation makes things look messy but better. by Akin Oyedele Business Insider March 14, 2017 Even Robert Shiller is worried about stock market valuations. The author of "Irrational Exuberance," a seminal book on volatility and behavioral economics that was released right as the dot-com bubble collapsed, is having flashbacks of that era. "The market is way overpriced," Shiller said, according to Bloomberg's Jason Clenfield and Adam Haigh. That is accurate by many measures, including Shiller's price-to-earnings ratio, which measures a stock's price relative to the last 10 years of the company's earnings. Its most recent reading on Monday was 29.24, a level not seen since the early 2000s when the internet bubble was leaking. Shiller likened the market's assessment of President Donald Trump's pro-business agenda to the awe that followed several internet companies as they grew in the late 1990s. Both periods can be described as "revolutionary," Shiller told Bloomberg, but investors are too focused on the positives and not so much the downside of Trump's agenda.

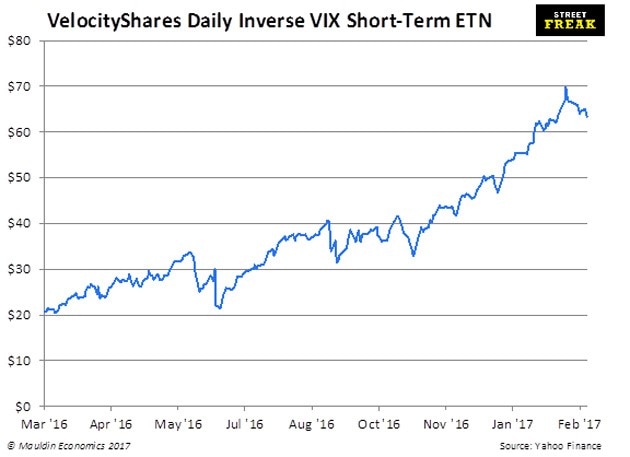

He did not forecast a short-term decline in stocks, but told Bloomberg that he wasn't buying more. The benchmark S&P 500 index has gained 11% since the election. While a five-quarter streak of year-on-year earnings declines ended in the fourth quarter, the market was also propelled by expectations for tax cuts and deregulation. As there hasn't yet been much implementation, several strategists have argued that stocks are due for a pullback that won't necessarily end the eight-year-old bull market. by Jared Dillian The 10h Man - Mauldin Economics March 2, 2017 You might remember The Incredible Drinking Bird joke from an old Simpsons episode. Homer wants to take a break from work, so he gets The Incredible Drinking Bird to hit the same key on the keyboard for him while goes out for a beer. The Incredible Drinking Bird is sort of a perpetual motion machine—it has a felt beak that dips in a glass of water, and then some chemical stuff happens in that bowl in the tail as the water evaporates and the bird tips over again. I had a colleague at Lehman Brothers who joked that the French banks got The Incredible Drinking Bird to hit the “sell vol” key on their keyboards. They just sold calls and puts on a daily basis, driving the vol into the mid-single digits. We joked that they probably booked the entire premium of the option as profit at the time of sale. Looks like someone has The Incredible Drinking Bird out there selling vol again. Check out this chart—there is always a bull market somewhere: That’s the chart of the inverse VIX ETN. Yes, there is such a thing, though it only has just over $500 million in assets.

Interesting tidbit about XIV: if the VIX were to go up a lot—say, 80% in a day—then XIV would be forced to redeem. It’s happened before, nearly 10 years ago to the day. Speaking of which, do you remember where you were on February 27, 2007? That was the opening salvo of the financial crisis, the day when the ABX gagged and China raised reserve requirements. We went from zero to OMG in the span of an afternoon. I tell people this all the time—in my entire career, I have never seen anything that crazy. It was also the highest vol-of-vol day in history. There is a lot of vol selling out there. People are willing to sell puts and calls for not very much, just to get a little yield out of their portfolio. And this, boys and girls, is one of the direct consequences of Zero Interest Rate Policy—people are incentivized to take stupid risks just to get a little yield. There were rumors going around last week about a fund getting itself into trouble by selling 1x5 upside call spreads, covering billions of delta as the market rallied. Nobody knows for sure if that’s what was driving the stock market higher, but it was a plausible theory, and it’s exactly the kind of behavior that gets people in trouble. Stress Test Here’s an exercise that we should all go through right now. You should stress test your portfolio. Picture some hypothetical awful situation—North Korea lobs a nuke into San Francisco, a true black swan—and try to predict how your portfolio would react in that disaster scenario. Do you feel like you have adequate protection? Oftentimes, buying protection for events like this is prohibitively expensive. Not now, though—now it is about as cheap as it gets. There is no reason not to own it. A lot of people will misinterpret me and say, “Dillian thinks something really bad is going to happen.” That is not the case at all. Really bad things are really unlikely. All I’m saying is, the cost of protecting yourself against really bad things can’t get much lower. But I will also say that it’s in times when people are most complacent that they should be the most vigilant. Usually it is the other way around—people are most vigilant when they should be complacent (like in the teeth of the financial crisis). I have been picking up anecdotes here and there. I’m sure many of you have come home from work to watch the Nightly News, only to have your spouse observe that the Dow is making record high closes on a daily basis, are we making money? Whenever you hear stories like that—run! There is an old saying on Wall Street: Buy it when you can, not when you have to. You can buy the one month puts in the S&P at a 7 vol. You have to when they’re at a 40 vol. Not to mention common sense. If you think we are getting through four years of a Trump/Bannon administration with the market this soporific, you are nuts. You Might Want to Rethink That Instead of selling options, how about buying options? I’m sure there are lots of covered call writers on this distribution. How about you stop writing covered calls? You are getting virtually nothing. Let me rephrase that: You are trading away all the upside and getting virtually nothing in return. Same goes for selling cash-secured puts. Better to do that when vol is high, not when vol is low. I’ve talked a lot about buying downside protection, but why not buy some upside as well? I really like “right-tail” strategies in the index, like buying the long-dated 3000 strike calls in the S&P 500. It’s only about a 30% move—not all that improbable. Plus, you get all the rho.1 I know people who absolutely cannot bring themselves to buy an option. As they say, 90% of them finish out of the money.2 If nothing else, buying options is a good regret-minimization strategy. Think of it as investing in mental capital. Take a few thousand bucks and just spend it on being able to sleep soundly at night. Sounds like a good investment to me. _____ 1 Exposure to higher interest rates. 2 I have no idea if this is true. by George Friedman

Geoplitical Futures March 6, 2017 Chinese Premier Li Keqiang told the National People’s Congress that China’s GDP growth rate would drop from 7 percent in 2016 to 6.5 percent this year. In 2016, the country’s growth rate was the lowest it had been since 1990. The precision with which any country’s economic growth is measured is dubious, since it is challenging to measure the economic activity of hundreds of millions of people and businesses. But the reliability of China’s economic numbers has always been taken with a larger grain of salt than in most countries. We suspect the truth is that China’s economy is growing less than 6.5 percent, if at all. The important part of Li’s announcement is that the Chinese government is signaling that it has not halted a decline in the Chinese economy, and that more economic pain is on the way. According to the BBC, Li said the Chinese economy’s ongoing transformation is promising, but it is also painful. He likened the Chinese economy to a butterfly struggling to emerge from its cocoon. Put another way, there are hard times in China that likely will become worse. China’s economic miracle, like that of Japan before it, is over. Its resurrection simply isn’t working, which shouldn’t surprise anyone. Sustained double-digit economic growth is possible when you begin with a wrecked economy. In Japan’s case, the country was recovering from World War II. China was recovering from Mao Zedong’s policies. Simply by getting back to work an economy will surge. If the damage from which the economy is recovering is great enough, that surge can last a generation. But extrapolating growth rates by a society that is merely fixing the obvious results of national catastrophes is irrational. The more mature an economy, the more the damage has been repaired and the harder it is to sustain extraordinary growth rates. The idea that China was going to economically dominate the world was as dubious as the idea in the 1980s that Japan would. Japan, however, could have dominated if its growth rate would have continued. But since that was impossible, the fantasy evaporates – and with it, the overheated expectations of the world. China’s dilemma, like Japan’s, is that it built much of its growth on exports. Both China and Japan were poor countries, and demand for goods was low. They jump-started their economies by taking advantage of low wages to sell products they could produce themselves to advanced economies. The result was that those engaged in exporting enjoyed increasing prosperity, but those who were farther from East China ports, where export industries clustered, did not. China and Japan had two problems. The first was that wages rose. Skilled workers needed to produce more sophisticated products were in short supply. Government policy focusing on exports redirected capital to businesses that were marginal at best, increasing inefficiency and costs. But most importantly – and frequently forgotten by observers of export miracles – is that miracles depend on customers who are willing and able to buy. In that sense, China’s export miracle depended on the appetite of its customers, not on Chinese policy. In 2008, China was hit by a double tsunami. First, the financial crisis plunged its customers into a recession followed by extended stagnation, and the appetite for Chinese goods contracted. Second, China’s competitive advantage was cost, and they now had lower-cost competitors. China’s deepest fear was unemployment, and the country’s interior remained impoverished. If exports plunged and unemployment rose, the Chinese would face both a social and political threat of massive inequality. It would face an army of the unemployed on the coast. This combination is precisely what gave rise to the Communist Party in the 1920s, which the party fully understands. So, a solution was proposed that entailed massive lending to keep non-competitive businesses operating and wages paid. That resulted in even greater inefficiency and made Chinese exports even less competitive. The Chinese surge had another result. China’s success with boosting low-cost goods in advanced economies resulted in an investment boom by Westerners in China. Investors prospered during the surge, but it was at the cost of damaging the economies of China’s customers in two ways. First, low-cost goods undermined businesses in the consuming country. Second, investment capital flowed out of the consuming countries and into China. That inevitably had political repercussions. The combination of post-2008 stagnation and China’s urgent attempts to maintain exports by keeping its currency low and utilize irrational banking created a political backlash when China could least endure it – which is now. China has a massive industrial system linked to the appetites of the United States and Europe. It is losing competitive advantage at the same time that political systems in some of these countries are generating new barriers to Chinese exports. There is talk of increasing China’s domestic demand, but China is a vast and poor country, and iPads are expensive. It will be a long time before the Chinese economy generates enough demand to consume what its industrial system can produce. In the meantime, the struggle against unemployment continues to generate irrational investment, and that continues to weigh down the economy. Economically, China needs a powerful recession to get rid of businesses being kept alive by loans. Politically, China can’t afford the cost of unemployment. The re-emergence of a dictatorship in China under President Xi Jinping should be understood in this context. China is trapped between an economic and political imperative. One solution is to switch to a policy that keeps the contradiction under control through the use of repression. The U.S. is China’s greatest threat. President Donald Trump is threatening the one thing that China cannot withstand: limits on China’s economic links to the United States. In addition, China must have access to the Pacific and Indian oceans for its exports. That means controlling the South and East China seas. As we have previously written, the U.S. is aggressively resisting that control. Faced with this same problem in the past, Japan turned into a low-growth, but stable, country. But Japan did not have a billion impoverished people to deal with, nor did it have a history of social unrest and revolution. China’s problem is no longer economic – its economic reality has been set. It now has a political problem: how to manage massive disappointment in an economy that is now simply ordinary. It also must determine how to manage international forces, particularly the United States, that are challenging China and its core interests. One move China is making is convincing the world that it remains what it was a decade ago. That strategy could work for a while, but many continue viewing China through a lens that broke long ago. But reality is reality. China no longer is the top owner of U.S. government debt, an honor that goes to Japan. China’s rainy day fund is being used up, and that reveals its deepest truth: When countries have money they must keep safe, they bank in the U.S. China carried out a great – and impressive – surge. But now it is just another country struggling to figure out what its economy needs and what its politics permit. by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

23 February 2017 • 12:25pm The Telegraph Vast liabilities are being switched quietly from private banks and investment funds onto the shoulders of taxpayers across southern Europe. It is a variant of the tragic episode in Greece, but this time on a far larger scale, and with systemic global implications. There has been no democratic decision by any parliament to take on these fiscal debts, rapidly approaching €1 trillion. They are the unintended side-effect of quantitative easing by the European Central Bank, which has degenerated into a conduit for capital flight from the Club Med bloc to Germany, Luxembourg, and The Netherlands. This 'socialisation of risk' is happening by stealth, a mechanical effect of the ECB's Target 2 payments system. If a political upset in France or Italy triggers an existential euro crisis over coming months, citizens from both the eurozone's debtor and creditor countries will discover to their horror what has been done to them. Such a tail-risk is real. As I write this piece, four out of five stories running on the news thread of France's financial daily Les Echos are about euro break-up scenarios. I cannot recall such open debate of this character in the Continental press at any time in the history of the euro project. As always, the debt markets are the barometer of stress. Yields on two-year German debt fell to an all-time low of minus 0.92pc on Wednesday, a sign that something very strange is happening. "Alarm bells are starting to ring again. Our flow data is picking up serious capital flight into German safe-haven assets. It feels like the build-up to the eurozone crisis in 2011," said Simon Derrick from BNY Mellon. The Target2 system is designed to adjust accounts automatically between the branches of the ECB's family of central banks, self-correcting with each ebbs and flow. In reality it has become a cloak for chronic one-way capital outflows. Private investors sell their holdings of Italian or Portuguese sovereign debt to the ECB at a profit, and rotate the proceeds into mutual funds in Germany or Luxembourg. "What it basically shows is that monetary union is slowly disintegrating despite the best efforts of Mario Draghi," said a former ECB governor. The Banca d'Italia alone now owes a record €364bn to the ECB - 22pc of GDP - and the figure keeps rising. Mediobanca estimates that €220bn has left Italy since the ECB first launched QE. The outflows match the pace of ECB bond purchases almost euro for euro. Professor Marcello Minenna from Milan's Bocconi University said the implicit shift in private risk to the public sector - largely unreported in the Italian media - exposes the Italian central bank to insolvency if the euro breaks up or if Italy is forced out of monetary union. "Frankly, these sums are becoming unpayable," he said. The ECB argued for years that these Target2 imbalances were an accounting fiction that did not matter in a monetary union. Not any longer. Mario Draghi wrote a letter to Italian Euro-MPs in January warning them that the debts would have to be "settled in full" if Italy left the euro and restored the lira. This is a potent statement. Mr Draghi has written in black and white confirming that Target2 liabilities are deadly serious - as critics said all along - and revealed in a sense that Italy's public debt is significantly higher than officially declared. The Banca d'Italia has offsetting assets but these would be heavily devalued. Spain's Target2 liabilities are €328bn, almost 30pc of GDP. Portugal and Greece are both at €72bn. All are either insolvent or dangerously close if these debts are crystallized. Willem Buiter from Citigroup says central banks within the unfinished structure of the eurozone are not really central banks at all. They are more like currency boards. They can go bust, and several are likely to do so. In short, they are "not a credible counterparty" for the rest of the euro-system. It is astonishing that the rating agencies still refuse to treat the contingent liabilities of Target2 as real debts even after the Draghi letter, and given the self-evident political risk. Perhaps they cannot do so since they are regulated by the EU authorities and are from time to time subjected to judicial harassment in countries that do not like their verdicts. Whatever the cause of such forbearance, it may come back to haunt them. On the other side of the ledger, the German Bundesbank has built up Target2 credits of €796bn. Luxembourg has credits of €187bn, reflecting its role as a financial hub. This is roughly 350pc of the tiny Duchy's GDP, and fourteen times the annual budget. So what happens if the euro fractures? We can assume that there would be a tidal wave of capital flows long before that moment arrived, pushing the Target2 imbalances towards €1.5 trillion. Mr Buiter says the ECB would have to cut off funding lines to "irreparably insolvent" central banks in order to protect itself. The chain-reaction would begin with a southern default to the ECB, which in turn would struggle to meet its Target2 obligations to the northern bloc, if it was still a functioning institution at that point. The ECB has no sovereign entity standing behind it. It is an orphan. The central banks of Germany, Holland, and Luxembourg would lose some of their Target2 credits, yet they would have offsetting liabilities under enforceable legal contracts to banks operating in their financial centres. These liabilities occur because that is how the creditor central banks sterilize Target2 inflows. In other words, the central bank of Luxembourg would suddenly owe 350pc of GDP to private counter-parties, entailing debt issued under various legal terms and mostly denominated in euros. They could try printing Luxembourgish francs and see how that works. Moody's, Standard & Poor's, and Fitch all rate Luxembourg a rock-solid AAA sovereign credit, of course, but that only demonstrates the pitfalls of intellectual and ideological capture. It did not matter that the EMU edifice is built on sand as long as the project retained its aura of inevitability. It matters now. Bookmakers are offering three-to-one odds that a candidate vowing to restore the French franc will become president in May. What is striking is not that the Front National's Marine Le Pen has jumped to 28pc in one poll, it is that she has closed the gap to 44:56 in a run-off against former premier François Fillon. The Elabe polling group say they have never before seen such numbers for Ms Le Pen. Some 44pc of French 'workers' say they will vote for her, showing how deeply she has invaded the industrial bastions of the Socialist Party. The glass ceiling is cracking. The wild card is that France's divided Left could suppress their bitter differences and team up behind the Socialist candidate Benoît Hamon on an ultra-radical ticket, securing him a runoff fight against Ms Le Pen. The French would then face a choice between the hard-Left and the hard-Right, both committed to a destruction of the current order. That contest would be too close to call. Anything could happen over coming months in France, just as it could in Italy where the ruling Democratic Party is tearing itself apart. Party leader Matteo Renzi calls the mutiny a "gift to Beppe Grillo", whose euro-sceptic Five Star movement leads Italy's polls at 31pc. As matters now stand, four Italian parties with half the seats in parliament are flirting with a return to the lira, and they are edging towards a loose alliance. This is happening just as the markets start to fret about bond tapering by the ECB. The stronger the eurozone economic data, the worse this becomes, for pressure is mounting in Germany for an end to emergency stimulus. Whether Italy can survive the loss of the ECB shield is an open question. Mediobanca says the Italian treasury must raise or roll over €200bn a year, and Frankfurt is essentially the only buyer. Greece could be cowed into submission when it faced crisis. The country is small and psychologically vulnerable on the Balkan fringes, cheek by jowl with Turkey. The sums of money were too small to matter much in any case. It is France and Italy that threaten to subject the euro experiment to its ordeal by fire. If the system breaks, the Target2 liabilities will become all too real and it will not stop there. Trillions of debt contracts will be called into question. This is a greater threat to the City of London and the banking nexus of the Square Mile than the secondary matter of euro clearing, or any of the largely manageable headaches stemming from Brexit. Would anybody even be talking about Brexit in such circumstances? by Peter Boockvar

February 22, 2017 “Bull markets are born on pessimism, grow on skepticism, mature on optimism and die on euphoria.” - John Templeton You likely have heard that quote before from John Templeton, an investing hero of mine. My prior boss, another great investor, often cited it and I felt that it was an important guide in gauging what stage of a bull market we are in. Sentiment is an unusual thing as its driven by emotion that separates itself many times from underlying reality both up and down. Considering the relentless, almost parabolic rally since the election as we approach the 8th year of this bull market that is nearing the longest ever, how can we not ask ourselves whether we are in the “euphoria” stage of this bull run. Some say we need the participation of the retail investor in order to reach that level. I disagree as after two 50%+ bear markets in 15 years, that is not going to happen. Many have not and will not come back. Thus, we have only other ’emotion’ indicators to rely on and even those are really only helpful in retrospect. It was on January 12th, 2016 when an analyst at RBS said “Sell everything except high quality bonds…We think investors should be afraid.” He expected a “fairly cataclysmic year ahead.” The market bottomed a month later and the S&P 500 is up 30% since. I saw on TV last night with a headline titled “Best Move: Just Buy Everything?” Last week a writer at Marketwatch wrote “Here’s why you shouldn’t buy a stock ever again” in a fawn over passive, index investing. We know that the amount of Bulls in the weekly Investors Intelligence survey have only been seen a few times over the past few decades. They currently total 61.2 vs 61.8 last week. Bears are a microscopic 17.5. I’m no technician and only use overbought/oversold metrics as a background message fully understanding that when extreme in one direction, it can get more so but we are really, really stretched. The 14 day RSI in the NDX yesterday closed at 84.7, the highest since January 1992. It was 84.2 in January 2000. The index is up 11 out of 12 days and that down day totaled 1.7 pts. The technology sector within the S&P 500 is up 14 days in a row. Valuations don’t matter until they do and certainly haven’t mattered for a while but we can’t deny the fact of where stocks are trading relative to other historical peaks. Much of the ebullience is being driven by hopes over a large cut in the corporate tax rate. To put numbers to this, the Bloomberg US exchange market capitalization has increased by $2.5 Trillion since the day of the election. According to the CBO estimate, the US will take in $320 Billion in fiscal year 2017 in TOTAL corporate income taxes. Thus, if the entire corporate tax was eliminated, we’ve priced that in by 8 times and some of those corporations are privately held. I know that we’ll get regulatory relief and capital spending tax incentives that the market is celebrating but you get my point. Webster’s defines ‘euphoria’ as “a feeling of great happiness and excitement.” Applying that to the stock market is certainly slippery in that how do we apply and measure it but from what’s been seen since the election in a very aged bull market, I think it is only prudent to ask whether we’ve entered that final phase seen in other historical bull markets. When it matters and from what level, who the heck knows but it’s still important for every investor to have a sense of what stage we are in. Mortgage applications to buy a home fell 2.8% w/o/w to the lowest level since mid November and thus giving back all of the post election bump higher with higher mortgage rates the likely factor. They still though are up 9.5% y/o/y. Higher home prices and the cost of financing has pushed the first time household into renting even more. Refi’s fell 1% w/o/w and are lower by 40% y/o/y. Of note in Europe, the IFO German business confidence index rose 1.1 pts to 111, back to where it was in December but that’s still the best level since 2011. Both current conditions and expectations improved. IFO said “After making a cautious start to the year, the German economy is back on track.” If there is a country that eagerly awaits what Trumponomics will look like, it will be the export heavy German businesses. Lastly, we’ll get the FOMC minutes from the meeting three weeks ago but after hearing from Yellen last week and from other voting members, nothing new will be gleaned. March is a growing possibility for a rate hike we already know. by John Mauldin

19 February, 2017 Mauldin Economics Excerpted from Thoughts from the Frontline The global economy is orders of magnitude more intertwined than it was in the 1920s and ’30s. Let me list a few of its challenges for you, things that we have touched on in previous letters and a few new ones:

|

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed