|

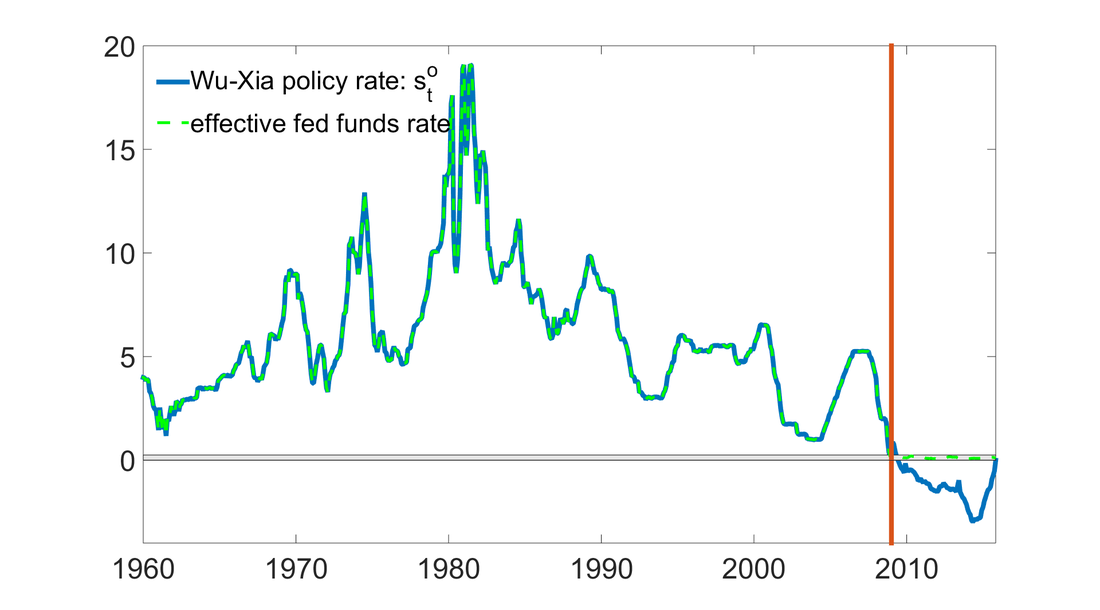

by John Hussman February 8, 2016 Weekly Market Comment Excerpts Though central bankers and talking heads on television speak about monetary policy as if it has a large and predictable impact on the real economy, decades of evidence underscore a weak and unreliable cause-and-effect relationship between the policy tools of the Fed and the targets (inflation, unemployment) that the Fed hopes to affect. One of the difficulties in evaluating the impact of monetary policy in recent years is that one can’t observe the relative aggressiveness of monetary policy using interest rates, once they hit zero. On that front, economists Cynthia Wu and Fan Dora Xia recently described a clever method to infer a “shadow” federal funds rate based on observable variables (see this University of Chicago article for a good discussion, and the original paper if you’re one of the five geeks who enjoy Kalman filtering, principal components analysis, and vector autoregression as much as I do). The chart below shows the Wu-Xia shadow rate versus the actual federal funds rate. Notably, the Fed doesn’t actually “control” the shadow rate directly, as it does when the Fed Funds rate is above zero. Rather, the shadow rate is statistically inferred using factors such as industrial production, the consumer price index, capacity utilization, the unemployment rate, housing starts, as well as forward interest rates and previously inferred shadow rates.

While it’s very useful to have an estimate of what the “effective” Fed Funds rate might look like at any point in time, be careful not to misinterpret what the shadow rate measures. Again, once interest rates hit zero, the Wu-Xia shadow rate stops being a measure of something that is directly controlled by the Fed. Rather, it measures the possibly negative “shadow” interest rate that would be consistent with the behavior of other observable economic variables. Like the rate of inflation, it’s not at all clear that the Fed can actively manage a negative shadow federal funds rate in a reliably predictable way. In any event, what’s striking from Wu and Xia’s paper is how feeble the estimated impact of QE has been on the real economy. Using vector autoregressions to estimate the trajectory of the economy under various monetary policy assumptions, Wu and Xia observe: “In the absence of expansionary monetary policy, in December 2013, the unemployment rate would be 0.13% higher... the industrial production index would have been 101.0 rather than 101.8... housing starts would be 11,000 lower (988,000 vs. 999,000).” Notably, the Wu-Xia plots of observed and counterfactual economic variables show the same result that we find in our own work: most of the progressive improvement in industrial production, capacity utilization, unemployment, and other economic variables since 2009 would have emerged regardless of activist Fed policy (see Extremes in Every Pendulum). We estimate that this also holds for the improvement in these variables since Wu and Xia's paper was published. Put simply, the Federal Reserve has created the third speculative bubble in 15 years in return for real economic improvements that amount to literally a fraction of 1% from where we would otherwise have been. It’s slightly amusing to hear alarm from some corners that the Wu-Xia rate has increased toward zero - as if the impact of this “tightening” on the real economy is something to be feared. That fear might be valid if there was a strong effect size linking changes in the shadow rate to changes in the real economy. But as Wu and Xia’s own work demonstrates, there is not. The entire global economy seems condemned to repeatedly suffer from deranged central bankers that wholly disregard the weak effect size of monetary policy on policy targets like employment and inflation, and equally disregard their responsibility for the disruptive economic collapses that have followed on the heels of Fed-induced yield-seeking speculation. In short, what we should fear is not the slight impact of recent policy normalizations, but the violent, delayed, yet inevitable consequences of years of speculative distortions that are already fully baked in the cake. What we should fear are the Fed’s repeated and deranged attempts to achieve weak effects on the real economy, at the cost of speculative distortions that exact ten times the damage when they unwind. What we should fear is more of the same Fed recklessness that encouraged a yield-seeking bubble in mortgage debt, enabling a housing bubble that collapsed to create the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. What we should fear is Fed policy that has encouraged a yield-seeking bubble in equities, debt-financed stock repurchases, and covenant-lite junk debt; that has carried capitalization-weighted valuations to the second greatest extreme in history other than the 2000 peak, and median equity valuations to the highest level ever recorded. That’s exactly what the Fed has done in recent years, and the cost of that unwinding is still ahead. Comments are closed.

|

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed